Introduction

The story of the crucifixion of Jesus is told in all four of the Gospels. Along with the resurrection, it is at the center of the Christian faith and images of it appear on many of the Irish High Crosses. This paper addresses the Irish High Cross images of the crucifixion from a number of perspectives. The photo below right is of the Durrow Cross, Co. Offaly.

First, the four narratives that relate the story of the crucifixion. These are found in the four Gospels of the New Testament. These narratives are the source of some, but not all, of the images found in the crucifixion scenes on the High Crosses.

First, the four narratives that relate the story of the crucifixion. These are found in the four Gospels of the New Testament. These narratives are the source of some, but not all, of the images found in the crucifixion scenes on the High Crosses.

Second, the theology of the crucifixion, how the crucifixion was understood, particularly during the first millennium, the time when the Irish High Crosses were carved.

Third, a general assessment of the images of the crucifixion on the fifty-eight crosses where a crucifixion scene appears.

Forth, descriptions, in general, of the divisions of the Irish High Crosses bearing crucifixion scenes as described by Peter Harbison, author of "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey” These are the Southeastern group, the Northern group, the Central group and the Later crosses.

Finally, following the Conclusions, each of the fifty-eight examples of the crucifixion on the Irish High Crosses listed by Peter Harbison are pictured and described using the approach of the Rev. Dom Louis Gougaud in an article entitled “The Earliest Irish Representations of the Crucifixion.” Gougaud assessed the images based on a variety of characteristics of the images that will be described below.

The Texts:

Each of the Gospels narrates the story of the crucifixion. Each has elements that are illustrated on the Irish High Crosses. Not every Gospel includes all the elements illustrated on the High Crosses. The Gospel passages that narrate the crucifixion are: Mark 15:22-37; Matthew 27:33-50; Luke 23:33-46 and John 19:16-37. Below, Mark’s narrative is quoted in its entirety. The items illustrated on the High Crosses that appear in Mark, and the other three Gospels, are identified in order to underline the fact that crucifixion images on the High Crosses are composite pictures of the story and other elements that are not in the narrative in any of the four Gospels.

Mark 15:22 Then they brought Jesus to the place called Golgotha (which means the place of a skull). 23 And they offered him wine mixed with myrrh; but he did not take it. 24 And they crucified him, and divided his clothes among them, casting lots to decide what each should take. 25 It was nine o'clock in the morning when they crucified him. 26 The inscription of the charge against him read, "The King of the Jews." 27 And with him they crucified two bandits, one on his right and one on his left. 28 29 Those who passed by derided him, shaking their heads and saying, "Aha! You who would destroy the temple and build it in three days, 30 save yourself, and come down from the cross!" 31 In the same way the chief priests, along with the scribes, were also mocking him among themselves and saying, "He saved others; he cannot save himself. 32 Let the Messiah, the King of Israel, come down from the cross now, so that we may see and believe." Those who were crucified with him also taunted him. 33 When it was noon, darkness came over the whole land until three in the afternoon. 34 At three o'clock Jesus cried out with a loud voice, "Eloi, Eloi, lema sabachthani?" which means, "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" 35 When some of the bystanders heard it, they said, "Listen, he is calling for Elijah." 36 And someone ran, filled a sponge with sour wine, put it on a stick, and gave it to him to drink, saying, "Wait, let us see whether Elijah will come to take him down." 37 Then Jesus gave a loud cry and breathed his last.

The first element in Mark’s narrative that is illustrated on the Irish High Crosses is the dividing of Jesus’ clothing. This image appears on the Cross of the Scriptures at Clonmacnois (County Offaly), the Durrow Cross (County Offaly) and possibly on the Tall Cross at Monasterboice (County Louth). I have discussed these images in a paper entitled “The Holy Week Images on the Irish High Crosses.” These images are not included here as part of the crucifixion scenes as they appear in other panels on the crosses.

The second element mentioned in the narrative is an inscription placed above Jesus’ head that read “The King of the Jews.” This element does not appear on any of the Irish High Crosses.

The third element that is illustrated is the crucifixion of two theives alongside Jesus. Each of the Gospels mentions these figures. While I do not describe these images, they appear on nine crosses. These crosses are: Clones, Carndonagh (?), Armagh composite cross, Arboe, Donaghmore crosses in both Counties Down and Tyrone, the Downpatrick cross in the museum, the Drumcliff cross and the west cross at Temple Brecan (?).

The forth element of the crucifixion narrative is the offering of sour wine to Jesus. This detail is not included in the Gospel According to St. Luke. The name generally given to this figure is Stephaton. Just when this name was given is not precisely known. Whether the Irish carvers of the cross had this name or not is a moot point. What we know is simply that the figure is included on as many as thirty-nine of the fifty-eight crosses with crucifixion scenes.

The fifth element of the crucifixion narrative in Mark, one that is repeated in each of the Gospels, is the death of Jesus. As will be discussed below in more detail, there are only a hand full of crosses that could potentially depict Jesus dead on the cross. One example is the Inishcealtra head fragment. There Jesus’ eyes appear to be closed and his head tilted down, perhaps indicating he is deceased.

The sixth element of the crucifixion often included on the high crosses is the presence of the guard who stabs Jesus in the side. This figure has been identified as Longinus and he uniformly appears paired with Stephaton, the sponge bearer. Thus, Longinus appears thirty-nine times, as does Stephaton. Longinus is mentioned here after the death of Jesus because he appears only in the account in the Gospel According to St. John (John 19:32-33).

A seventh element also appears only in the Gospel According to St. John, chapter 19 verses 25b- 27. “Meanwhile, standing near the cross of Jesus were his mother, and his mother's sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene. 26 When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple whom he loved standing beside her, he said to his mother, "Woman, here is your son." 27 Then he said to the disciple, "Here is your mother." And from that hour the disciple took her into his own home.” In several instances it may be possible to interpret figures in the crucifixion scenes as the Virgin Mary and St. John. These possible identifications can be made on the Muiredach Cross at Monasterboice and the east and west faces of the South Cross at Graiguenamanagh.

Two additional elements appear on some of the High Cross scenes of the crucifixion. They are angels and/or birds. These elements are not present in scripture.

The Theology of the Crucifixion

The scriptures from the Gospels describe the events of the Crucifixion but do not address its meaning. In this section of the paper I propose to offer some insights into the theology of the cross as explained by the Apostle Paul and reflected in the work of two early theologians, Origin (c.a. 182-254) and Chrysostom (347-407). This is by no means an exhaustive study of the theology of the cross. In the Conclusion I will consider whether this theology had any influence on the manner in which Jesus is typically depicted on the Irish High Crosses.

The meaning, the theology of the cross, is addressed first by the Apostle Paul, whose writings recorded in the New Testament predate the Gospels. Scriptures typically cited as offering Paul’s views on the crucifixion include: Romans 3:21-26; Romans 5:8-11; Romans 6:1-11 and 2 Corinthians 5:14-21.

Paul makes it clear that the meaning of the crucifixion is revealed in the resurrection. The two cannot be separated. This is made clear in Romans 5:10 which reads, “For if while we were enemies, we were reconciled to God through the death of his Son, much more surely, having been reconciled, will we be saved by his life.” According to St. Paul the problem for which the death and resurrection of Jesus is an solution is the problem of sin. In Romans 3:23 Paul’s assumption is that “all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.” Paul then makes use of a variety of metaphors to describe how the death of Jesus is a solution to the problem of sin.

In Romans 3:21-26 Paul makes use of the terms justification, redemption, a sacrifice of atonement and a passing over of “sins previously committed.’ N. T. Wright, author of “The Letter to the Romans” in the New Interpreter’s Bible, Vol. X, suggests that, from the point of view of the time in which Paul lived, the work of salvation required a faithful Jew. The faithfulness of Jesus the Messiah offered this faithful Jew. Wright states ““It was, then, thinkable in Paul’s period that the suffering of the righteous Jew might in some way atone, as a sacrifice did, for Israel.” (Wright p. 475) This notion was consistent with the role of the Suffering Servant as described in Isaiah chapters 40-55. Paul is clear that the initiative for this rests with God. Through the Incarnation, God provided Jesus, the faithful Jew. What happened in the crucifixion and resurrection was an act of God’s grace, the culmination of the “story of God’s love, active in Christ and the Spirit to do for humans what they could never do for themselves.” (Wright p. 471)

In Romans 5:8-11 Paul repeats the premise that sin is the problem. Humans on their own cannot be saved “from the wrath of God” (Romans 5:9b) through their own efforts. However, God, acting through the death of Jesus his son offers justification. In spite of human sin we are reconciled to God. N. T. Wright puts it this way: “We are reconciled, he [Paul] says, through the death of God’s son.” . . . “Jesus as ‘Son of God’ is the one sent from God to accomplish that which God alone must perform.” (Wright p. 520)

In Romans 6:1-11, Paul makes use of the image of baptism to say that the follower of Jesus has shared in the death and resurrection of Jesus. As one is buried in the waters of baptism one shares the death of Jesus, a death that freed him and those who follow him from bondage to sin. In rising from the waters of baptism, the believer is reborn into a new life, sins set aside, and reconciled to God through Jesus the Christ. N. T. Wright sums up by writing “It seems to me preferable to suppose that Paul is continuing to regard baptism as in some way a re-enactment of Jesus’ death, a making real for the individual of the once-for-all event of Calvary.” (Wright p. 539)

In II Corinthians 5:14-21 Paul wrote “we are convinced that one has died for all; therefore all have died.” (II Cor. 5:14b) The implication of this is that anyone who is “in Christ”, who is a follower of Jesus and has received baptism, is reconciled to God and now shares in Jesus the Christ’s ministry of reconciliation. J. Paul Sampley, author of “The Second Letter to the Corinthians” in the New Interpreter’s Bible Vol. XI, writes “The claim that Christ died ‘for all’ . . . should be taken, not in a substitutionary manner in the sense of Christ’s taking everybody’s place at his death, but in the sense of Christ’s being for — that is, siding with — people.” According to this logic, the death of Jesus the Christ is an act of God’s love, grace and forgiveness.

In summary, Saint Paul believed that the death of Jesus the Christ on the cross was effective for salvation. In his death and resurrection, God released those who believe in Jesus the Christ from bondage to sin and brought about forgiveness that resulted in reconciliation. The problem of sin was resolved, once and for all, for those who believed. As A.C. Purdy, author the article on the Apostle Paul in the Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible wrote: “The death of Christ carries the note of the cost of sin and the costly character of God’s act in Christ.” (Purdy, p.p. 695-6)

Origen, an early proponent of the Ransom theory of the Atonement, offers some opinions about the crucifixion in his Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans. In commenting on Romans 3:21-24 Origen wrote: “Let us look carefully at the meaning of ‘redemption which is in Christ Jesus.’ The term ‘redemption’ refers to that which is given to enemies for those who they are keeping in captivity, in order that they might restore them to their original freedom.:” This payment for the release of the prisoner is a ransom. Origen goes on to say that the Son of God “gave himself as the redemption price, that is to say, he handed himself over to the enemies and, what is more, poured out his own blood to those thirsting for it; and this is the redemption accomplished for those who believe.” (Origen p. 215) Thus the thinking of Origen was that Jesus’ death on the cross, the shedding of his blood was the price paid by Jesus to purchase the freedom from sin that was necessary to redeem or rescue those who believe from bondage to sin. This Ransom theory of the cross was typical of Christian theology in the first millennium.

Saint John Chrysostom, author of the “Apologist” referred back to the Book of Isaiah in his reflection on the cross. “Isaiah also established that the slaying of Christ was the ransom for man’s sins by saying: ‘He has borne the sins of many.’ And he freed mankind from demons for, as Isaiah said: ‘He will divide the spoils of the strong.’ And the same prophet spoke out clearly that Christ did this through his death when he said: ‘Because his soul was delivered up to death.’” (Chrysostom, Apologist, pp. 207-208) He is referring here to the discourse in Isaiah on the “suffering servant.”

In another work, Discourses Against Judaizing Christians, Chrysostom suggests that in thinking about the cross “There is no need, then, to grieve or be downcast; we must rejoice and glory in all these things.” Chrysostom then goes on to express just why there is joy rather than grief when considering the cross. “‘But God commends his charity towards us, because when as yet we were sinners, Christ died for us.’ John put it like this: God so loved the world.’ Tell me, how did God love the World? John passed over all the other signs of God’s love and put the cross in first place. For after he said: ‘God so loved the world,’ he said: ‘That he gave his only-only-begotten Son,’ that he be crucified, ‘that those who believe in him may not perish but may have life everlasting.’ If, then the cross is the basis and boast of love, let us not say that it is a cause for grief.” (Chrysostom, Discourses, p. 62)

There are several facets of the theology of the cross to highlight. First, the crucifixion cannot be separated from the resurrection. If, following the Ransom Theory of the cross, the death of Jesus on the cross was a payment for sin that Jesus could make as the “faithful Jew”, then the resurrection was an affirmation that the debt was paid and life outside of the control of sin was offered to those who believe. Second, the cross and the resurrection are an act of God’s love and grace. Third, as Paul suggests, by baptism the believer shares in the death and resurrection of Jesus. Finally, the cross is not a cause for grief but a cause for joy. This final point has potentially significant implications for the Irish manner of depicting the crucifixion. The way Jesus is depicted, as described below, speaks of Jesus in control of the situation and victorious over it. The images speak both of the crucifixion and the resurrection. More on this in the conclusion (page 28)

The Depiction of the Crucifixion in early Christian Ireland

There are fifty-eight images, or supposed images of the crucifixion on the surviving Irish High Crosses and cross fragments. In an article entitled “The Earliest Irish Representations of the Crucifixion”, the Rev. Dom Louis Gougaud described characteristics of the scenes of the crucifixion on Illuminated manuscripts, the sculptured stone crosses and in metal work. In this paper he looks at the crucifixion scenes by examining characteristics of the figure of Jesus and of other accompanying figures included in some of the scenes. I have chosen to follow this model for examining the crucifixion scenes on the High Crosses.

Peter Harbison divides the crucifixion scenes on the Irish High Crosses into two main groups: earlier crucifixions and later crucifixions. The earlier crosses he divides into three sub-groups: the Southeastern group; the Northern group and the Central group. (Harbison, 1992, 273) He divides the later crucifixions into two sub-groups based on how Christ is clothed. In one group he wears a long robe, in the other group only a perizonium or loin-cloth. (Harbison, 1992, p. 284) Acknowledging this method of assessing the High Crosses I will follow Gougaud’s model first with respect to the total grouping of fifty-eight crosses and then subsequently assess each sub-group of the earlier crucifixion scenes separately and the entire group of later crucifixion scenes together.

The Entire Group of Crosses containing a Crucifixion Scene

Placement of the Crucifixion Scenes

With only a few exceptions, the crucifixion appears on the head of the cross. The exceptions are Carndonagh, Moone, the South Cross at Clonmacnois and the Patrick and Columba Cross at Kells. In these cases the scene appears either on the shaft or the base. In addition in the vast majority of cases the images appears on the west face of the cross, or what may have originally been the west face. (Harbison, 1992, p. 273)

Quality of the Carving

Gougaud was highly critical of the nature of the carving in the crucifixion scenes. I quote him at length. “The entire want of skill of most of the ancient Celtic artists and craftsmen in their attempts to represent the human figure is notorious. The most august of all the religious subjects appears in our eyes as a veritable caricature, though executed by men who were far from having any such intention.; It is not necessary to lay stress on the absence of pathos in these crucifixions, when not only dignity, but any kind of expression and even any elementary notion of anatomy are complete lacking.” (Gougaud p. 132) This applies to all the figural art on the crosses.

The Cross

In the majority of the depictions of the crucifixion the figure of Jesus is contained within the center of the head of the cross. In these cases it is very rare to see any indication of a cross within the cross to which the body of Jesus is attached. One example of this is the North Cross at Castledermot (see the image to the left). The arms of Jesus do not reach into the arms of the cross and there is no indication of him hanging on a smaller cross within the panel. This can be seen more clearly in the cases where the crucifixion is not in the center of the head of the cross. The image of the crucifixion at Moone (see the image below right) is on the base of the cross. There is no indication of a cross behind the figure of Jesus.

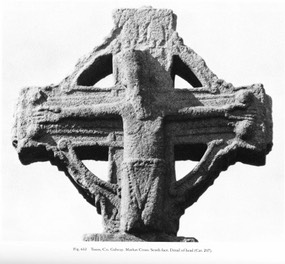

These two images can be contrasted with the image of Jesus on the Tuam Market Cross (see the image below left) where Jesus’ arms reach to the ends of the arms of the cross and he can be easily understood as hanging on the main cross.

Statistically, on nineteen of the fifty-eight crosses the arms of Jesus reach into the arms of the main cross. In twenty-nine cases they do not and in ten cases it is unclear.

Consistent with any image representing the crucifixion, in every case where the arms of Jesus are visible he is depicted with arms outreached. However, on only three of the crosses are Jesus’ arms angled up, as would be realistic of one hanging on a cross. These examples are Monaincha, Colp and Carndonagh. The cross at Monaincha is pictured to the right. In contrast, in twelve cases the arms of Jesus are clearly angled downward, not a position that would be expected of one crucified. One example of this is the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois, pictured below right. In another thirty-two instances the arms of Jesus are depicted as reaching out perpendicularly. An example of this can be seen at Dysert O’Dea as pictured below left. This is another unexpected posture for one hanging on a cross.

The prevalence of images where Jesus’ arms are perpendicular or slope downward suggests a posture of victory rather than defeat. Of course the placement of the arms is, in most cases at least partly a function of the shape of the center of the cross and may not have been intentionally designed to, in a sense, communicate the victory of resurrection as well as the defeat of death by crucifixion. Other facets of the appearance of Jesus also seem to carry this message of victory, as will be noted below.

The Head of Jesus

In fifty of the fifty-eight images of the crucifixion on the High Crosses the head of Jesus is straight up so that his body is fully erect. The photos of the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois and the Dysert O’Dea Cross on the page above are examples of this. In six cases Jesus’ head is tilted to one side or the other. The image of the Glendalough Market Cross, pictured to the right is an illustration of this.Another feature of the head of Jesus are the eyes. In most cases it is impossible to discern whether the eyes of Jesus are open or closed. If, as has often been suggested, the crosses were originally painted, this would have been clear. There are as many as twelve of the  fifty-eight crosses where Jesus’ eyes appear to be open. One of the best examples of this is the Killaloe Cross, originally from Kilfenora, pictured to the left. This image is from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 399. In one instance, the Head Fragment from Inishcealtra, located presently in the National Museum at Dublin, the eyes of Jesus appear to be closed. The photo to the right below is from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 322.

fifty-eight crosses where Jesus’ eyes appear to be open. One of the best examples of this is the Killaloe Cross, originally from Kilfenora, pictured to the left. This image is from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 399. In one instance, the Head Fragment from Inishcealtra, located presently in the National Museum at Dublin, the eyes of Jesus appear to be closed. The photo to the right below is from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 322.

The upright position of Jesus’ head on most of the crosses combined with the impression of open eyes on about twenty per cent of the examples, suggests once more that Jesus is depicted as crucified but in control of the situation if not clearly victorious over it.

Hair and Beard

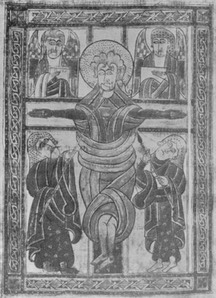

Emphasizing Gougaud’s statement that the depictions of human characters on the High Crosses in general are veritable caricatures, there are only a few examples of the crucifixion on the High Crosses where Jesus is depicted with much if any hair, or indeed with a beard. This is not only unexpected given our traditional contemporary images of Jesus, it is also very different from the depictions of Jesus on the cross in the illuminated Gospels. One example is the image of Jesus crucified in the Saint Gall Gospels. A close-up of the head in that illustration is pictured to the right. The full image is from Gougaud, Plate 7, Figure 1, facing page 128. In this example Jesus is without a beard but he has curly hair that is quite full. On only two of the fifty-eight crucifixion scenes on the High Crosses is there a clear indication of hair that is of any significant length. These examples are the Roscrea Cross and the Tory Island Tower Cross. The Roscrea Cross is illustrated to the left.

On only three crosses does Jesus clearly have a beard. These are the Inishcealtra Head Fragment, the Roscrea Cross pictured to the left and the Tuam Market Cross. The Inishcealtra Head Fragment illustrated above is the clearest example.

One other feature appears related to Jesus’ head, but on rare occasions. On several crosses there is the appearance of a crown or crown of thorns or a halo. We have seen above that on the Tuam Market Cross and the Glendalough Market Cross it appears that Jesus wears a relatively tall crown. On the Moone Cross and the Unfinished Cross at Kells there is what appears to be a partial halo behind Jesus’ head.

Position of Jesus’ Feet

In most of the crucifixion scenes on the High Crosses Jesus appears to be standing rather than hanging. On twenty-seven of the crosses his feet are depicted as apart and untied. The Galloon Head Fragment pictured below to the left is an example of this. On ten additional crosses his feet are apart but appear to be tied. The Arboe Cross pictured below right is an example. In only four instances do Jesus’ feet appear to be together and on none, where the feet appear, is one on top of the other, as is often depicted on the crucifixes of a later period. An example of the feet being together, is found on the West Cross at Kilfenora pictured below center. There are sixteen crosses where Jesus’ feet are either not depicted or are so vague as to eliminate description. The general position of the feet and the fact that Jesus appears to be standing rather than hanging suggests, as above, that while Jesus is depicted as the crucified one, he is also depicted as in control of his destiny and victorious.

Another attribute that appears occasionally on the High Crosses is the presence of a suppedaneum or foot support for Jesus’ feet. In the example from the Cashel Cross Jesus stands on a foot rest that is atop a pillar, giving the impression of a “T” shaped suppedaneum. See the photo below right. This feature, though in a much simpler form also appears on the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois, the Dysert O’Dea cross and the Kilfenora West Cross.

Jesus’ Clothing

There is significant diversity in the clothing in which Jesus is depicted. In at least thirty-seven cases he appears to wear a tunic. In thirteen cases the tunic is long, typically reaching to the ankle. The North Cross at Graiguenamanagh, pictured to the right is an example of this. In another thirteen instances the tunic is short, reaching just to or slightly above the knee. The Galloon Head Fragment, the Arboe Cross and the West Cross at Kilfenora, all pictured on the previous page, offer examples of this. In three instances is it clear that there are sleeves on the tunic as is the case with the North Cross at Graiguenamanagh to the right. In another three instances the garment Jesus wears is described as rope-like. These crosses are: the Tall Cross at Monasterboice, the Patrick and Columba Cross at Kells and the Drumcullin Cross. The Tall Cross at Monasterboice, pictured to the left offers an example of Jesus’ upper body and arms appearing to be covered with such rope-like attire.

This is similar to the treatment of Jesus’ clothing in some of the Illuminated manuscripts. An excellent example of this can be seen on the Saint Gall Gospels referred to above. To the left the entire illustration from Gougaud is offered.

On three crosses, the Tuam Market Cross pictured to the right, The Graiguenamanagh South cross, east face and the Glendalough Market Cross, Jesus wears a loin-cloth. In the photo to the right this is made particularly clear with a decorated triangle covering Jesus.

Another mode of attire that appears can be described as a close fitting garment, giving the appearance of a body suit. This occurs on at least fifteen of the High Crosses. One example of this type of attire is the North Cross at Monasterboice pictured to the left. In these cases it almost appears that Jesus is without clothing.

Nails

There are only three crosses on which nails clearly appear. These crosses are the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois, the Muiredach Cross and the Tall Cross at Monasterboice. Of course this may not have been true on the crosses when they were first carved and painted. It is entirely possible that nails were painted on the hands and feet. In other cases wear or breakage has made it difficult or impossible to identify nails. On the Tall Cross at Monasterboice nails are present in both the hands and feet of Jesus, though this is difficult to discern in the image above right. Those in the feet are most clearly present. This is, however, the only one of the crosses where nails appear in the feet. In the other two examples they are present in the hands only. The real or apparent lack of nails in the images of the crucifixion again raises the question of the intention of the depictions of the crucifixion on the High Crosses. Is Jesus intended to be depicted as both crucified and triumphant?

There are only three crosses on which nails clearly appear. These crosses are the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois, the Muiredach Cross and the Tall Cross at Monasterboice. Of course this may not have been true on the crosses when they were first carved and painted. It is entirely possible that nails were painted on the hands and feet. In other cases wear or breakage has made it difficult or impossible to identify nails. On the Tall Cross at Monasterboice nails are present in both the hands and feet of Jesus, though this is difficult to discern in the image above right. Those in the feet are most clearly present. This is, however, the only one of the crosses where nails appear in the feet. In the other two examples they are present in the hands only. The real or apparent lack of nails in the images of the crucifixion again raises the question of the intention of the depictions of the crucifixion on the High Crosses. Is Jesus intended to be depicted as both crucified and triumphant?

Stephaton and Longinus

Two of the iconic figures that form part of a full crucifixion scene are Stephaton, the person who offered Jesus sour wine on the end of a pole, and Longinus, the person who stabbed Jesus in the side with a spear. The names of these two figures do not appear in scripture but developed in the tradition of the church. The figure of Stephaton appears in each of the four Gospels except The Gospel According to St. Luke. The figure of Longinus appears only in the Gospel According to St. John. Yet, when they are depicted in the crucifixion scene they always appear together. These figures clearly appear on twenty-six of the fifty-eight crosses with another possible thirteen appearances. They are missing on eighteen of the crosses. In general, when the pole and spear, the attributes of these two figures, are present, Stephaton tends to appear on the left and Longinus on the right. An example of this arrangement is found on the Unfinished Cross at Kells pictured to the right. An example of Longinus on the left and Stephaton on the right can be seen on the Arboe Cross pictured to the left. On twenty-two of the crosses Stephaton is on the left and Longinus on the right. In the images where Stephaton and Longinus are present, or likely to be present they appear as figures on each side of Jesus, under his arms, but without their attributes of pole and spear. In these cases it is possible but unlikely that they represent others figures such as the Virgin Mary and Saint John. An example of the two without their attributes can be seen on the West Face of the South Cross at Graiguenamanagh pictured to the right. The figures are just visible, one at each side of Jesus.

As noted above, Stephaton is the pole bearer who offered Jesus sour wine on a sponge attached to end of his pole. On forty-four of the crosses it is not possible to discern anything on the end of Stephaton’s pole. In some cases the upper portion of the pole has simply disappeared. There are five crosses where it does appear that a sponge or a vessel is at the end of the pole. These are the Moone Cross, the Unfinished Cross at Kells, the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois, the Patrick and Columba Cross at Kells and the Muiredach Cross at Monasterboice. On the Patrick and Columba Cross at Kells, pictured to the right, there is a form under what appears to be Jesus’ chin. It could be a beard but more likely represents either a vessel or sponge on the end of Stephaton’s pole. The Unfinished Cross at Kells, pictured below, also has an object at the end of the pole, as does the Moone Cross pictured to the left.

Angels and Birds

On about half of the High Crosses with crucifixion scenes either angels or birds appear. In general the angels are paired with one on each side of Jesus’ head as on the Unfinished Cross at Kells, pictured below right. Occasionally there will be one angel and it will be depicted above the head of Jesus as on the Termonfeckin Cross, pictured below left.

The Durrow Cross pictured below right, and the Cross Head from Durrow, pictured below left. The Durrow photo is from Harbison, 1992, Fig.260. Both have a bird above the head of Jesus. In these cases it has been suggested that the birds may represent the Holy Spirit.

Sol, Luna, Tellus and Gaia

On two of the crosses at Kells, the Market Cross, pictured to the right, and the Patrick and Columba Cross pictured to the left below, there are bosses or figures that may represent Sol (the sun) or Luna (the moon) or perhaps Tellus (the waters) or Gaia (the earth). In the case of the Market cross Sol and Luna seem to be represented by bosses located behind Stephaton and Longinus. The figure of Tellus also seems to appear as a crouching figure beneath the feet of Jesus. On the Patrick and Columba Cross there is a figure on either side of Jesus’ head where we might expect to find angels. The figure on the left faces Jesus’ head while the figure on the right faces away and holds an object. Harbison has suggested these figures could represent either Sol and Luna or Tellus and Gaia. He wrote: “To the left of Christ’s head a small seated figure with raised knees holds up an unidentified object. On the other side, a second seated figure — also with tucked-up knees — has its back to Christ. The discs above their heads — that on the left having a trail behind it — could suggest that the figures represent the Sun on the left and the Moon on the right though they could also be interpreted as Ocean and Earth (with a water jar) respectively.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 110)

The Virgin Mary and St. John

The Virgin Mary and St. John may appear on the Muiredach Cross at Monasterboice and the east and west faces of the South Cross at Graiguenamanagh. In the case of the Muiredach Cross at Monasterboice the figures identified above as Sun and Moon or Tellus and Gaia have been identified by Macalister as the Virgin Mary and St. John. Harbison identifies this as “improbable.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 145) In the case of the Graiguenamanagh South Cross the figures generally identified as Stephaton and Longinus without their attributes could represent the Virgin and St. John. These identifications are speculative.

The Early Southeastern Crosses

This group of crosses, as identified by Harbison, consisted of seven crosses. They are: Castledermot North and South, Graiguenamanagh North, Moone, Newtown, St. Mullins and Ullard.

Placement of the Crucifixion Scenes

On six of these seven crosses the crucifixion scene appears on the head of the cross. The exception is the Moone Cross where the crucifixion appears on the base of the cross. In four of the seven examples the crucifixion appears on the east face of the cross and in the other three cases it appears on the west face of the cross.

The Cross

In none of the examples in the southeast group is there the appearance of a cross within the crucifixion panel to which Jesus might be attached. On the Graiguenamanagh North Cross and on the St. Mullins cross Jesus’ arms reach into the arms of the larger cross, suggesting he may be hanging on the main cross.

The Head of Jesus including Hair and Beard

In each case the figure of Jesus has his head erect and in at least three examples the eyes appear to be open. In four instances it is unclear whether the eyes are open or closed or the eyes are not clearly visible. On six of the crosses in this group hair is not obvious and could be described as short or non-existent. On the Castledermot North Cross there is a figure atop Jesus’ head that could represent hair or a crown of thorns as shown in the photo below right. On the Moone Cross there is an indication, difficult to see, of a halo behind Jesus’ head. See the image below left.

In no instance in this group does Jesus have a beard.

Position of Jesus’ Feet

In the six examples in this group where Jesus’ feet are visible, his feet are apart, giving the impression he is standing. In none of these examples are his feet tied. In none of these examples does Jesus appear to have a suppedaneum beneath his feet.

Jesus’ Clothing

In at least six of the seven examples in this grouping, Jesus wears a tunic, and this is probably also true of the seventh, the Newtown Cross. (Photo from Harbison 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 525) In this case, shown in the photo to the right it is difficult to clearly discern Jesus’ attire partly because his legs and feet are not clear.

Nails

There are no nails apparent in Jesus’ hands or feet. As noted in the general survey of all the crosses, it is possible that nails were painted on as part of the decoration of the crosses.

Stephaton and Longinus

Stephaton with his pole and Longinus with his spear probably appear on each of these crosses. On the St. Mullins Cross their images are abbreviated and could represent Sol and Luna or Stephaton and Longinus. In three instances, the Graiguenamanagh North Cross, the Newtown Cross and the St. Mullins Cross Stephaton and Longinus do not have their attributes. In these cases they cannot be distinguished from one another. In the cases where they have their attributes, Longinus appears on the left in three of the four instances. Among all the High Crosses with crucifixion scenes there is only one other image where Longinus is depicted on the left. Thus this group of crosses is notable for this difference from the norm. Only one of these crosses clearly depicts a sponge or vessel at the end of Stephaton’s pole. This appears on the Moone Cross, pictured on the previous page.

Angels and Birds

On six of the seven crosses in this group there are angels present. On the Graiguenamanagh North Cross these appear above Jesus’ head. On the St. Mullins Cross the figures identified as angels are simple bosses, as they now appear. On the Moone Cross there are no angels present.

Sol, Luna, Tellus and Gaia

These figures do not appear on any of the crosses in this grouping.

The Early Northern Group

This group includes thirteen crosses. They are: Arboe, Armagh, Carndonagh, Clones, Donaghmore (Co. Down), Donaghmore (Co. Tyrone), Downpatrick, Drumcliff, Galloon head fragment, Galloon lost head fragment, the Unfinished Cross at Kells, Killesher, and the Tynan Well Cross.

Placement of the Crucifixion Scenes

With the exception of the Carndonagh Cross where the crucifixion scene is located on the shaft of the cross, the scene appears on the head of these crosses. In each case it appears that the scene is limited to the crossing of the shaft and crossbar.

The Cross

There is no appearance of a small cross behind Jesus, except on the Unfinished Cross at Kells. In that case it appears there was intended to be a crossbar behind Jesus’ arms.

The Head of Jesus including hair and beard

On each of the thirteen crosses Jesus’ head is erect. In one case, the Lost Head fragment at Galloon, his head is tilted to one side. On two crosses, Carndonagh and Killesher, Jesus’ eyes appear to be open. On the others in this group it is unclear whether the eyes are open or closed. No hair or beard is depicted on any of these crosses. On the Unfinished Cross at Kells, Jesus appears to have a halo behind his head.

Position of Jesus’ Feet

On eight of the crosses the feet of Jesus are apart, and in one case, Donaghmore Tyrone, Jesus’ feet appear to be together. In another four cases it is not clear how the feet are depicted. None of these crosses show an obvious suppedaneum.

Jesus’ Clothing

On ten of the crosses it appears that Jesus wears a tunic. In four cases the tunic is long, in five cases the tunic is knee length and in one case, Clones, the length is uncertain. On the Lost Head Fragment at Galloon and the Tynan Well Cross it is difficult to discern Jesus attire. At Killesher, Jesus wears a close-fitting garment.

Nails

Nails are not present on any of these crosses.

Stephaton and Longinus

On seven of the crosses Longinus is depicted on the right while Stephaton is on the left. These crosses are: Armagh, Clones, Donaghmore (Tyrone), Drumcliff, Galloon Head Fragment, Galloon Lost Head Fragment and the Unfinished Cross at Kells. On the Arboe cross this arrangement is reversed. On an additional four crosses, Carndonagh, Donaghmore (Down), Downpatrick and Tynan Well, there are no attributes to distinguish one from the other. On the cross at Killesher Stephaton and Longinus do not appear. On two crosses, Armagh and Kells Unfinished, there is what appears to be a bucket or other vessel at the end of Stephaton’s pole. On the Killesher Cross Stephaton and Longinus do not appear.

Angels and Birds

On ten of the crosses angels appear on each side of Jesus’ head. There are no angels present on the crosses at Drumcliff, on the Galloon Lost Head Fragment and Killesher.

Sol, Luna, Tellus and Gaia

No images of these figures appear on the thirteen crosses in this grouping.

The Early Central Group

There are seventeen crosses in this grouping. They are: Balistric, Castlebernard/Kinnitty, the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois, Colp, Drumcullin, Duleek North and South, Durrow, the Durrow head, the Kells Market Cross, the Patrick and Columba Cross at Kells, the Muiredach Cross and the Tall Cross, North Cross and Head Fragment from Monasterboice, Termonfechin and Tihilly.

Placement of the Crucifixion Scenes

Within the Central group there is one example, the Patrick and Columba Cross at Kells, where the crucifixion appears on the shaft of the cross. There are four examples, including the cross head from Durrow and the Termonfeckin Cross where the arms of Jesus seem to reach into the arms of the cross. In contrast, there are eleven examples where the crucifixion scene is contained within the center of the cross, extending only into the narrowings of the arms.

The Cross

There are no instances in this group where a small cross appears behind the body of Jesus. However on the Colp Cross the arms of Jesus angle slightly upward, suggesting that his is actually hanging on a cross.

The Head of Jesus

On fifteen of the Central crosses the head of Jesus is upright. On the Tall Cross at Monasterboice the head of Jesus is in profile and tilts back to the left. On the North Cross at Duleek the head of Jesus tilts slightly to the right. In the other fifteen cases the head of Jesus is upright. None of the crosses in this group show clearly that Jesus’ eyes are open. Hair does not clearly appear on most of these crosses. However, there is either a cap or hair depicted on the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois, the Durrow Cross and the North Cross at Monasterboice. On the Patrick and Columba Cross at Kells, what may be seen as a beard is more likely the sponge or vessel on the end of the pole held by Stephaton. It is also possible that Jesus has a beard on the Tall Cross at Monasterboice. There are no halos or crowns on Jesus head in this grouping unless the cap or hair described above can be interpreted as such.

Position of Jesus’ Feet

In ten instances in this group the feet of Jesus are tied. Still, in every case where Jesus’ feet are visible, his feet are slightly apart. In only one instance, the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois, is there a suppedaneum present.

Clothing

On ten of the seventeen cross in this group Jesus is clothed in a tight-fitting garment. The Muiredach Cross at Monasterboice is one example of this. In three instances all or part of Jesus garment appears to be rope-like. These crosses are the Drumcullin Cross, the Patrick and Columba Cross at Kells and the upper part of Jesus’ garment on the Tall Cross at Monasterboice. In two examples, the Ballistic Cross and the Colp Cross, Jesus appears to be clothed in a tunic.

Nails

Nails are visible on three of the crosses in this grouping. These crosses are the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois, the Muiredach Cross and the Tall Cross at Monasterboice.

Stephaton and Longinus

Stephaton and Longinus appear on thirteen of the seventeen crosses in this group. In each case Stephaton is on the left and Longinus on the right. In two other instances they are probably indicated. On the Colp cross-head they appear without their attributes. On the cross-head from Durrow they may be represented by bosses under the arms of Jesus. A sponge or vessel appears on the end of Stephaton’s pole in four instances. They are: The Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois, the Durrow Cross, the Patrick and Columba cross at Kells and the Muiredach Cross at Monasterboice.

Angels

Two angels appear, one on each side of Jesus’ head, on the South Cross at Duleek, the Patrick and Columba Cross at Kells and the Muiredach Cross at Monasterboice. On the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois and possibly on the Tihilly Cross one angel appears above the head of Jesus. On the Colp and Kinnitty Crosses it is possible there were angels. On the Durrow Cross there is a bird above Jesus’ head, possibly representing the Holy Spirit. On the Durrow cross-head there is also a bird above Jesus’ head that seems to be flying to the left. This may also have represented the Holy Spirit.

Sol, Luna, Tellus and Gaia

At Monasterboice, on the Muiredach Cross and the Tall Cross images of Sol and Luna appear. On the Muiredach Cross, at the level of Jesus’ knees and in front of Longinus and Stephaton there is a boss on each side. These have been interpreted as Sol and Luna. On this same cross, behind Longinus there is a figure that kneels with its back to Jesus and may hold a child. Harbison identifies this figure as Gaia, a personification of earth. Behind Stephaton there is a figure that seems to sit with knees up. Harbison identifies this figure as Tellus, a personification of water. (Harbison, 1992, p. 145)

The Later Crosses

There are twenty-one crosses in this group, making the later crosses the largest of the four groups. The crosses are: Addergoole, Cashel, Dysert O’Dea Glendalough Market Cross, Graiguenamanagh South Cross on both the east and west faces, the Inishcealtra head fragment the Doorty and West Crosses at Kilfenora, Kilgobbin, the Killaloe cross and Cross Shaft, the Killeany fragment and the Killeany Cross-head, monaincha, Roscrea, Temple Brecan North, South and West, Tory Island Tower Cross, and Tuam Market Cross. Harbison sub-divides this grouping into those crosses where Jesus is depicted in a long robe and those in which he wears a loin-cloth. These differences will appear below when the clothing of Jesus is described.

Placement of the Crucifixion Scenes

Crosses. On two of the crosses the figure of Jesus fills the entire face of the cross. These crosses are: Cashel and the Glendalough Market Cross. On a number of crosses the crucifixion image is contained in the head of the cross but the arms of Jesus extend into the arms of the cross. There are eleven of these examples. Here, as with those noted above where Jesus’ body fills the whole face of the cross, it is easy to imagine that Jesus is actually attached to the main cross. I include Addergoole, an unfinished cross that appears to have intended Jesus to fill the head of the cross and perhaps extend partly into the shaft in this group. There are two crosses where the crucifixion scene is confined to the center of the head of the cross. These are: Graiguenamanagh South on the west face and Kilgobbin. On two additional crosses the crucifixion scene is located on the shaft of the cross. These crosses are the Killaloe shaft fragment and Temple Brecan South. There are four cross fragments where it is difficult, or impossible because of breakage, to determine which of the categories above they fit. The Inishcealtra head fragment is one example, where only the head of Jesus is preserved. The other examples in this category are Killeany and Temple Brecan North, and West.

The Cross

There are an unusual number of crosses in this group where there seems to be a small cross behind Jesus, one he is attached to. This is true of the crosses listed above where the form of Jesus fills the entire face of the cross and of those where the arms of Jesus extend into the arms of the larger cross. Those that specifically appear to have a smaller cross to which Jesus is attached include Roscrea and Tuam.

The Head of Jesus

On twenty of the crosses the head of Jesus is up. In one of these instances, the Addergoole Cross, the head is tilted to the right, on the Glendalough Market Cross and the Tuam Cross the head is tilted to the left. On seven of the crosses it appears that Jesus’ eyes are open and on the remaining fourteen it is unclear. Those where his eyes appear to be open are: Dysert O’Dea, Kilfenora Doorty Cross, Kilfenora West Cross, Killaloe Cross, Killeany head, Temple Brecan North Cross.

On nineteen of the crosses Jesus appears to have short hair or none at all and on two he is depicted with long hair. Those in which he has long hair are Roscrea and Tory Island Tower Cross. On eighteen of the crosses Jesus has no beard while on three he is depicted as bearded. These include the two crosses where Jesus has long hair as well as the Inishcealtra Head Fragment. On the Glendalough Market Cross and the Tuam Cross Jesus appears to wear a crown.

Position of Jesus’ Feet

On nine crosses Jesus’ feet appear to be apart. These crosses are Dysert O’Dea, Graiguenamanagh South both east and west face, Killaloe Cross-shaft, Killeany, Temple Brecan North, South and West, and Tory Island Tower Cross. On three crosses, Cashel, Glendalough Market and Kilfenora West his feet appear to be together. On nine crosses the position of the feet is uncertain, largely because, in most cases the feet are not visible. None of the crosses in this group have Jesus’ feet tied or otherwise bound. On eighteen of the crosses there is no suppedaneum while on three, Cashel, Dysert O’Dea and Kilfenora West, there is a suppedaneum. That on the cross at Cashel is unique as it has the appearance of a tau cross with a base topped by the suppedaneum.

Clothing

On three of these crosses, the Glendalough Market Cross, the Graiguenamanagh South Cross, east face and the Tuam Market Cross, Jesus appears to wear a loin cloth. On four crosses, the Graiguenamanagh South Cross, west face, the Kilfenora Doorty Cross, the Kilfenora West Cross and the Killaloe Cross, he is clothed in a tunic that reaches the knee. On six crosses, the Kilgobbin Cross, the Killeany cross, the Killeany Head fragment, the Monaincha Cross the Roscrea Cross and the Tory Island Tower Cross, Jesus wears a tunic that is long. He also wears a long tunic, this time with sleeves at Addergoole, Cashel and Dysert O’Dea. On five crosses he wears what can be described as a tight fitting garment, almost a body-suit. These crosses are: The Killaloe Cross-shaft, Temple Brecan North Cross, Temple Brecan South and Temple Brecan West.

Nails

Nails do not appear on any of the crosses in this group.

Stephaton and Longinus

Stephaton and Longinus appear on only five of these crosses. They are: Graiguenamanagh South both east and west faces, Killeany and Temple Brecan North and West. In the case of the Graiguenamanagh South Cross the figures identified as Stephaton and Longinus could also be Mary the Mother of Jesus and the Apostle John. Only on the Killeany Cross can the two be identified by their attributes. In this instance Longinus is on the right and Stephaton on the left. The sponge or bucket does not appear on any of the crosses.

Angels

By and large the Later Crosses do not contain images of angels. Of the twenty-one crosses in this grouping only three are likely to have either angels or birds. There may be angels present on either side of Jesus’ head on the west face of the Graiguenamanagh South Cross. The same is true on the Killaloe Cross with angels probably above the arms of Jesus. On the Tuam Cross, above Jesus’ head are two figures that may or may not be related to the crucifixion. If they are related, they could be either angels or birds.

Mary and John

As noted above, it is possible that the figures under Jesus’ arms on both faces of the Graiguenamanagh South Cross could be Mary the Mother of Jesus and the Apostle John. Because of the lack of attributes any definite identification is impossible.

Conclusions

In the section above on the Theology of the Cross it is noted that the crucifixion of Jesus cannot be separated from the resurrection. This suggests that images of the crucifixion on the Irish High Crosses may be intended to represent both Jesus’ death and resurrection; both his sacrifice and victory. Indeed the prevalent theology of the cross in the first millennium, the atonement theory, suggests that it is the crucifixion that pays the debt incurred by sin. This was seen as good news.

The typical presentation of the crucifixion scene on the Irish High Crosses appears to support this theology. There are numerous indications. In general Jesus’ head is upright and where visible, his eyes appear to be open. This suggests Jesus is alive and alert. This may have been more prominent if the crosses were indeed painted. In most examples, the arms of Jesus either stretch straight out or drop down slightly. This is probably a function of the shape of the cross head, but suggests a Jesus who is upright and more nearly extending arms in an embrace than hanging on a cross. In nearly every case Jesus appears to be standing whether with feet apart or together, whether his feet are tied or not. This gives the impression that that Jesus is in control of the situation rather than a victim. In most of the depictions of the crucifixion on the Irish High Crosses Jesus appears to be clothed in a tunic or a close-fitting body suit. In only a few examples is he depicted in a loin-cloth. This may be a nod to modesty but it also sends a message of the preservation of the dignity of Jesus, even on the cross. One aspect of removing the clothing of those crucified was to strip them of their dignity and humanity. If this is true, it once again lifts up Jesus as one who is in control of the situation and victorious. The absence of nails, while it may be a result of deterioration of the stone or disappearance of paint, is another indication of this impression of victory.

These conclusions are, of course, based on what we can observe now and on descriptions offered by Peter Harbison and other High Cross scholars. To the degree that they are accurate they offer the scene of the crucifixion on the Irish High Crosses as a sign of God’s love, mercy and forgiveness, a cause of joy rather than grief.

High Cross Crucifixion Scenes Described

For a description of each of the 58 crucifixion images on the Irish High Crosses see the next page on this website.

Bibliography

Chrysostom, Saint John, “Apologist”, Margaret A. Schatkin and Paul W. Harkins translators, The Catholic University of America Press, Washington, D.C.1983.

Chrysostom, Saint John, Discourses Against Judaizing Christians, Paul W. Harkins translator, The Catholic University of America Press, Washington, D.C., 1977

Gougaud, Dom Louis and Armstrong, E.C.R., The Earliest Irish Representations of the Crucifixion, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries, No. 2 (Dec. 31, 1920), pp. 128-139.

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

New Revised Standard Version of the Bible

Origen, Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans Books 1-5, Thomas P. Check translator, The Catholic University of America Press, Washington, D.C., 2001

Purdy, A.C., “The Apostle Paul” The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, Abingdon Press, Nashville, 1962, pp. 695-696.

Sampley, J. Paul, The Second Letter to the Corinthians, The New Interpreter’s Bible, Vol. XI, Abingdon Press, Nashville, 2002, p. 92

Wright, N.T., The Letter to the Romans, The New Interpreter’s Bible, Vol. X, Abingdon Press, Nashville, 2002. pp. 468-478.