Crosses of County Antrim

This page explores three High Crosses found in County Antrim. They are Broughanlea, Connor, and Tullaghore. The location of County Antrim is noted by the blue star on the map to the right.

Antrim History in the Celtic and Early Christian Periods.

During the early Celtic period, up to about 500 CE, the area of Antrim was peopled by the Darini. (O’Rahilly, p. 7) In the early Christian period what is now County Antrim was part of the kingdom of Ulaid. At this time the area was limited to modern “Antrim, Down and north (and possibly south) Louth.” (McSparron p. 107) The dynastic areas in Antrim included “the Dal nAraide of south and north-west Antrim and the Dal Riata of north-east Antrim.” (McSparron p. 107) By the Convention of Druim Cett in 575, the kingdom of Dal Riata was closely allied to the northern Ui Neill. In 637 at the battle of Mag Roth, the combined forces of the Dal Riata and Dal NAraide, in rebellion against the Ui Neill, were defeated making the Ui Neill dominant in the north of Ireland. (McSparron p. 108) From the late eighth century up to the twelfth century the Fir Li, who had moved east of the River Bann became dominant in much of present day County Antrim. In 1177 the Anglo-Normans invaded Ulaid and by 1182 had established five bailiwicks: Antrim, Carrickfergus, Ards, Blathewic and Lecale.

Father John Musther, Rector of the Orthodox Parish of St. Bega, St Mungo and St Herbert, Keswick, in Cumbria, England, in his website earlychristianireland.net, lists 22 early Christian sites in present day County Antrim, suggesting a strong early Christian presence in the area. As noted above, only three of these sites have early stone crosses. They are: Broughanlea, Connor, and Tullaghore.

The Broughanlea Cross:

The Church, the Bishop and the Cross

Little is known about the origins of this cross, the church it is associated with or the bishop who was first given charge of the church. The first mention of the church appears in the Tripartite Life of Patrick. It reads, in part: “Patrick left many churches and cloisters in the district of Dal Riata . . . bishop Fiachra in Cuil Echtrann.” (p. 163) Bishop Fiachra is the only church leader mentioned in connection with this church and this may be the only mention of him in the literature.

Whitley Stokes, writing in 1887 offers a date for the Tripartite Life of Patrick in the late tenth or early eleventh century. He refutes those who would give it a middle sixth century date, citing both historical and linguistic reasons for his later dating. The author of the Tripartite Life is not known.

H. C. Lawlor, writing in 1937 identifies Cuil Echtrann, more currently known as Cuifeightrin, with a churchyard at Magherintemple, about one half mile south of the current location of the cross, where it was moved in about 1790.By 1937, when H. C. Law lor wrote about the Broughanlea Cross he described the Magherintemple church site as “obliterated”. In 1887, some fifty years before, James O’Laverty described remains of the church site including “the east gable the east end of the north sidewall and a small piece of the south sidewall.” (O’Laverty, p. 463)e dating of the cross is another unknown. Lawlor believed the cross may well date from the late fifth or early sixth century and represent a tribute to St. Fiachrius (Fiachra). In possible support of this hypothesis is the crude, ringless shape of the cross. The presence of two croziers, “one crook - and the other tau-shaped, carved in false relief may suggest a connection with the Desert Fathers. (Harbison, 1992, p. 30) There is some speculation that these two croziers are meant to represent the ministries of Saints Paul and Anthony of the Desert. The crook being identified with St. Paul and the tau with St. Anthony. There is a long tradition that traces the origins of Irish Monasticism to the influence of the Desert Fathers and Mothers as brought to western Europe by people like John Cassian. Cassian was born in present day Romania about 360. By the early fifth century he was visiting with some of the Desert Fathers and through him their teachings spread to Western Europe by the early fifth century. (Ramsey, pp. 5-6)

lor wrote about the Broughanlea Cross he described the Magherintemple church site as “obliterated”. In 1887, some fifty years before, James O’Laverty described remains of the church site including “the east gable the east end of the north sidewall and a small piece of the south sidewall.” (O’Laverty, p. 463)e dating of the cross is another unknown. Lawlor believed the cross may well date from the late fifth or early sixth century and represent a tribute to St. Fiachrius (Fiachra). In possible support of this hypothesis is the crude, ringless shape of the cross. The presence of two croziers, “one crook - and the other tau-shaped, carved in false relief may suggest a connection with the Desert Fathers. (Harbison, 1992, p. 30) There is some speculation that these two croziers are meant to represent the ministries of Saints Paul and Anthony of the Desert. The crook being identified with St. Paul and the tau with St. Anthony. There is a long tradition that traces the origins of Irish Monasticism to the influence of the Desert Fathers and Mothers as brought to western Europe by people like John Cassian. Cassian was born in present day Romania about 360. By the early fifth century he was visiting with some of the Desert Fathers and through him their teachings spread to Western Europe by the early fifth century. (Ramsey, pp. 5-6)

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 5 D2. The cross is just beside the A2 on the south side of the road and across from the Colliers Hall B&B, east of Ballycastle. The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

The Connor Cross

The Church and the Cross

The name Connor is derived from the Irish Con Doire, meaning the oak wood of the wolf. In the Early Christian period there was a settlement that included both monastic and secular elements. No saint or bishop is mentioned in connection with the foundation of this monastary and church. The Map of Monastic Ireland indicates that at some point in time Connor was a Bishopric and that it continued in existence after 1111.

Writing in 1902, George Buick states that the partial shaft of a High Cross was found during the digging of a grave in the church graveyard. The family of the deceased decided to erect it at the head of the grave. It remained there for some years until a Cannon of the church named Fitzgerald decided the shaft needed to be moved inside to protect it. Accordingly, he had the cross shaft moved to the vestry of the church. Apparently he failed to receive the approval of the family associated with the grave. As a result they broke into the vestry and smashed the cross into several pieces. Cannon Fitzgerald had the cross repaired and moved it to the basement of the rectory. It was there in 1902 when George Buick viewed it and wrote about it. (Buick, pp. 243-245)

The cross has figural carving on one face and one side. The only clear images are on the face, where there are two panels. There are two different thoughts about the interpretation of each of these panels. we will consider them one at a time.

Lower Panel: Buick identifies this image with the story of the Judgment of Solomon. Harbison identifies it with the story of Cain slaying Abel. (Buick, pp. 243-245 and Harbison, 1992, p. 60) The story of the Judgment of Solomon appears in 1 Kings 3:16-28. It concerns two women, identified as prostitutes, who live in the same house. Each had a baby. The child of one died and the mother took the baby of the other woman and claimed it as her own. When Solomon ordered that the baby be cut in half and each woman be given half, the real mother pleaded that the child should be given to the other woman. If this is the proper identification, it would seem there would be a baby in the image. If there is, it is difficult to identify. In addition, the two largest figures would have to be identified as the two women and the smaller figure to the right with Solomon. That would be unusual.

The story of Cain Slaying Abel appears in Genesis 4, especially verse 8. “And when they were in the field, Cain rose up against his brother Abel and killed him.” In order to make this identification, Harbison suggests that the figure to the left is God, standing behind Cain with a hand on his shoulder. The text does continue with God asking Cain where his brother Abel is. The Cain figure seems to be holding a weapon above the head of Abel. Harbison’s identification seems more persuasive that that of Buick.

Upper Panel: Buick identifies this scene with the story of Aaron and Hur holding up the arms of Moses as he prays for victory over the armies of the Amalekites. Harbison identifies it as Joseph being lifted from the pit and sold into slavery. (Buick, pp. 243-245 and Harbison, 1992, p. 60) The story story of the Hebrews against the Amalekites is told in Exodus 17:8-13. While Moses was able to hold up his arms in prayer the Hebrew army was winning. When his arms became tired and he dropped them, the Amalekites rallied. So Aaron and Hur held up the arms of Moses and the Hebrews won the battle. It is possible that Moses was kneeling to pray. It is clear that the figures on the left and right of the frame are supporting the central figure. It would be expected that the arms of Moses would be more obviously up or out to the sides as an expression of prayer. This does not seem to be the case.The story of Joseph being sold into slavery is found in Genesis 37:27-28. It indicates “they drew Joseph up and lifted him out of the pit.” The position of the legs of the central figure and the apparent actions of the figures on the left and right seem to fit well with this interpretation.

Side Panel: Harbison suggests a possible identification for the partial panel on the side of the cross. Based on what is visible, just the right edge of the panel, he suggests it may represent the story of the Sacrifice of Isaac. The story is told in Genesis 22:1-19. There appears to be a human figure in the lower right corner of the panel. This figure may be holding an ax and is leaning over to the left, perhaps over an altar.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 11 C2. The Cross is located inside St. Saviour’s Church (Church of Ireland) at Connor. Connor is located along the B59 just east of the A26. Follow sign postings to Kells and Connor. The church is generally locked, the parsonage is just to the east of the church and church hall. The map below is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

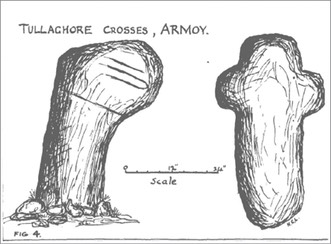

The Tullaghore Cross:

There are two small and very crude crosses located east of the Armoy church. There does not seem to be anything known about the origins of these crosses. The illustration above is from the Lawlor article cited below. The cross to the right above is undecorated, but clearly in the shape of a cross. The cross to the left, which may represent the right side of a broken cross, has what appear to be “two interlocking croziers, placed horizontally above a groove.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 178) I was unable to locate the cross to the right in the illustration to the right.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 5 C/D 4. The site is located along the B15 east of Armoy, the Armoy-Glenshesk Road. It is near the top of a ridge, in the field just in front of a modern farmhouse. The farm drive is 1.8 km east of the Armoy Round Tower. The map below is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Resources Cited

Buick, Geo. R., “A Further Notice of the Connor Ogams, and on a Cross at Connor”, The Journal of the royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 32, No. 3, (Sep 30, 1902), pp. 239-245.

Harbison, Peter; The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey, Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Lawlor, H. C. “Some Primitive Crosses in Counties Antrim and Down”, The Irish Naturalists’ Journal, Vol. 6, No. 123 (Nov., 1937), pp. 294-297

McSparron, Cormac; Williams, Brian and Bourke, Cormac; “The excavation of an Early Christian rath with later medieval occupation at Drumadoon, Co. Antrim”, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, lCulture, History, Literature, Vol. 109C (2009), pp. 105-164.

Map of Monastic Ireland, Ordinance Survey Office, 1964.

O’Laverty, James, “An Historical Account of the Diocese of Down and Connor,” Vol. 4, 1878.

O’Rahilly, Thomas F., Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1964.

Ramsey, Boniface, translator and editor, “John Cassian: The Conferences” Newman Press, Mahwah, New Jersey, 1997.

Stokes, Whitley, “Tripartite Life of Patrick” Part I, 1887, London.Harbison, Peter; The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey, Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.