The crosses of County Tipperary include: Ahenny North, Ahenny South, Ardane Large cross head, Ardane Small cross head, Ballynilard, Cashel St. Patrick’s, Emly, Lorrha North, Lorrha South, Mona Incha, Roscrea, Roscrea Pillar and Toureen Peakaun. The location of County Tipperary is indicated by the red star on the map to the right.

Historic Background

The modern County Tipperary has been part of the province of Munster from antiquity. This area was inhabited far back into prehistory.

The Mesolithic and Neolithic Ages (4500 to 2500 BCE)

An excavation in the Ashleypark townland of County Tipperary revealed a neolithic burial mound with a tomb that contained the bones of an adult male and a child. The radio-carbon date for the femur of the adult dates to between 3350 and 3650 BCE. (Manning, et. al., p 61)

The Bronze Age (2500 to 500 BCE)

In advance of the development of the N8 Cashel-Mitchelstown road improvement, archaeological surveys identified forty sites that spanned the Neolithic through the Late Bronze Age. One example is a settlement site at Ballydrehid that contained two settlement structures.

The Iron Age (500 BCE to 400 CE)

The introduction of Iron work seems to have coincided with the arrival of the Celtic people and their language about 500 BCE. Archaeological features include crannogs, promontory forts, ring forts and souterrains. Hillforts actually appeared in the late Bronze Age and continued through the Iron Age. In County Tipperary there are examples of contour forts at Ahenny (well known for its High Crosses), Ballincurra and Kedrah. In addition there are enclosure hillforts at Curraghadobbin, Kilbragh and Liss. (Hillforts)

The Early Christian Period (400 to 1000 CE)

At the opening of the Christian era in Ireland the Eoganachta dominated the area around the Rock of Cashel. The Eoganachta gradually expanded to dominate the Kingdom of Munster from the 6th through the 10th centuries. In the 11th and 12th centuries the control of Munster was gradually taken over by the Dal Cais, the tribal group of Brian Boru. In the 12th century the Kingdom of Munster was divided by the Treaty of Glanmire into the southern kingdom of Desmond and the northern kingdom of Thomond. What is now County Tipperary was largely in the Kingdom of Thomond.

The Eoganachta were descendants of Conall Corc, but were named for his ancestor Eogan. The Eoganacht developed into several branches. The three main branches, those who most frequently held the kingship of Munster, were the Eoganacht Chaisil of County Tipperary; the Eoganacht Glendamnach of northern County Cork and the Eoganacht Aine of east County Limerick (near Emly). These three were descended from Oengus mac Nad Froich (died 489) During the 7th and 8th centuries these three inner branches rotated the Kingship of Munster. During the 9th and 10th centuries most of the kings came from the Eoganacht Chaisil.

There were other branches that were not part of the inner circle. These included: the Eoganacht Raithlind in south County Cork; the Eoganacht Locha Lein in Kerry and the Ui Fidgente south and southwest of Limerick City. These branches were descended from brothers of Nad Froich, who founded the inner branches. (Charles-Edwards pp. 534-6)

Beginning in 970 and extending through 1119, with one interruption, the Dal gCais began to provide the kings of Munster. Their early territory was in the area around the city of Limerick. The second of these Kings, 978-1014, was Brian Boruma mac Cennetig. Brian’s capital was at Kincora, near present day Killaloe. This interrupted the rule of the Eognacht that dated back to the fifth century. It was during the rule of the O’Briain’s, in 1101, that the rock of Cashel was given to the Church.

Lennox Barrow, in an article entitled “The Rock of Cashel” suggests that

“this gift may not have been unconnected with his desire to frustrate the ambitions of the rival Eoghanacht dynasty whose claims to the Rock were rather stronger than his own.” (pp. 133-4)

Less than twenty years later, in 1118, the Treaty of Glanmire divided the Kingdom of Munster into Desmond and Thomond. Much of Tipperary was included in the Kingdom of Thomond.

Ecclesiastical History

Saint Patrick was active in what is now Munster as early as 456. The Tripartite Life reports that Patrick spent seven years in Munster. (Tripartite Life p. 109) It is reported that he converted and baptized Oengus Mac Nad Froich, king of Munster at Cashel, the capital, during this time. Interestingly, as stated below, the origins of the church/monastery at Cashel is not credited to St. Patrick, or indeed to anyone. It is worth noting that St. Patrick founded churches, not monasteries. He was working out of the Roman diocesan system. He left bishops to care for these churches. In some cases, when monasticism became prevalent in Ireland, some of these church sites became the locus for monasteries. Nevertheless, in the lists of Irish monasteries, many are credited to St. Patrick. Oddly, only one Tipperary Monastery is credited to St. Patrick, that being Glenkeen. Even in this case, it is noted that the monastery might have been founded by St. Culan. The scarcity of churches/monasteries attributed to St. Patrick in what is now County Tipperary is striking. This is especially true related to Cashel, where Patrick is not credited with establishing a church/monastery there, given the tradition that he baptized the King at the foot of the Rock of Cashel. In an article entitled “Munster, Saints of (act. c. 450-c.700)” by Elva Johnston we have a hint that a church at Cashel was founded long after there was a church at Emly, possibly, though Johnston does not specifically suggest this, not until the Rock of Cashel was given to the church in 1101. (Johnston)

It seems clear that Patrick was not the first promoter of the Christian faith in Munster, or in County Tipperary specifically. There was a group of what have come to be called pre-Patrician Munster saints. Johnston identifies Ailbe, Ciaran the elder, Declan and Ibar and four pre-Patrician saints. While tradition sees them as pre-Patrician, the Irish Annals date them after St. Patrick. But this may have had to do with politics, Munster having accepted the primacy of Armagh by the seventh century. (Johnston)

One of these pre-Patrician saints, Ailbe (Albeus) was the founder of the church at Emly, in what is now County Tipperary. While Ailbe was a member of the Dal Cairpri Arad, a minor Munster tribal group, the church at Emly came to be supported by the Eoghanacht and many of the abbots there came from various of the Eoghanacht groups. Emly was the most important church in Munster for several centuries. As late as the twelfth century, Emly became an episcopal see. (Johnston)

Lenox Barrow states that the early kings of Cashel were “frequently but not invariably bishops as well.” (Barrow, p. 133) I have been unable to determine to what extent this statement is accurate. That there was a connection between church and state in early Christian Ireland is common knowledge. Frequently the Abbots of monasteries came from the royal family. However, if, as Johnston alludes to in her article, there was no church/monastery at Cashel while it was the capital of the Eoganacht kings it would follow there were no abbots, and that the kings did not serve in that capacity.

As stated above, one significant event in church history related to County Tipperary took place in 1101. It is generally known as the First Synod of Cashel. The Synod was convened by Muirchertach Ua Briain as king of Ireland. The results are debated but it was one of a series of church synods in Ireland that began to reform the Irish church and bring it into conformity with the Roman church. The most significant event at this particular synod may well have been the gift of the Rock of Cashel to the church.

Below is a listing of the early monasteries of County Tipperary. The earliest of these appear to be Glenkeen and Emly. As noted above Glenkeen has been attributed to either St. Patrick or St. Culan. Emly was founded by St. Ailbe who died in 528. Of these monasteries, those having High Crosses include: Ahenny (listed below as Kilclispeen), Ardane, Ballynilard, Cashel, Emly, Lorrha, Mona Incha, Roscrea, and Toureen Peakaun. Ardane and Ballynilard are not included in the listings below. This is almost certainly due to a lack of historic information about these sites.

Ardcrony,early site

Ardfinnan, early site, founded 7th century? by Finan Lobhar

Cashel, early site

Cluain-conbruin, early site, founded by St. Abban

Clonfinglass, early site, founded by St. Abban

Coninga, early site, founded by St. Declan of Ardmore

Daire-mor, early site, founded mid 7th century

Derrynavian, early site, founded pre-800

Donaghmore, early site, founded 6th century by Farannan

Donaghmore, early site, founded by St. Erc of Donaghmore?

Emly, early site, founded 5th/6th century by St. Ailbe

Glenkeen, early site, founded 5th century by St. Patrick or St. Culan

Holy Cross Abbey, early site, hermit monks?

Inishlounaght Abbey, early site, founded pre-656 by St. Pulcherius

Kilcash, early site, founded by St. Colman ua hEirc?

Kilclispeen/Ahenny, early site, cross remains

Kilkeary, early site, nuns, founded pre-679

Kilmore, early site

Latteragh, early site

Leamakevoge, early site, founded by St. Mochemoc

Lemdruim,early site

Lorrha, early site, founded pre-558 by St. Brendan

Molough Priory, early site, nuns, founded late 5th century

Monaincha Priory, early site, Culdee hermits, founded 6th century

Roscrea, early site, founded 7th century by St. Cronan

St. Peakaun, early site, founded by St. Abban?

Senros, early site

Shanrahan, early site, founded pre-c637 by St. Cataldus

Terryglass, early site, founded pre-549 by St. Colum

Toomyvara Priory, early site, founded 6th/7th century by St. Donan

Tullamain, early site

The Ahenny Monastic Site (Kilclispeen)

What do we know about the monastery that was located at Ahenny? After considerable research on line and in the books available in my library, I concluded that Halpin and Newman sum it up perfectly when they write “nothing is known of its history -- probably because the original name of the site has been lost and replaced by a later dedication to St Crispin.” (Halpin, Newman, 434) As nothing is known of the history of the monastery, so too, nothing is known of an Irish saint named Crispin.

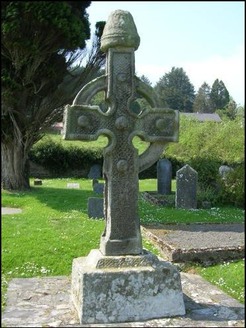

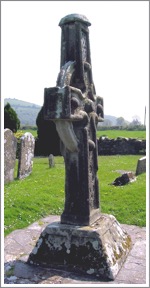

The ancient Monastic site of Kilclispen [lies] in a small fertile valley running north into the Slievenamon hills.” (Meehan, p. 496) A short distance to the east is the river Linguan that separated Ossary from Munster in ancient times and separates County Tipperary from County Kilkenny at the present time. The photo below shows the cemetery. The view is to the east.

The supposition is that a monastery flourished here, founded between the 5th and 7th centuries. (www.megalithic.co.uk) That the monastery flourished is testified to by the presence of two High Crosses and the base of another. Whether founded in the 5th, 6th or 7th century, it was thriving during the 8th century, when it is supposed the crosses were carved. They have been identified as among the earliest of the Irish High Crosses. The original name of the site is not known, but at some point in history, the site was given the name Kilclispeen, St. Crispin’s Church. The ruins of a late medieval church are located on the site.

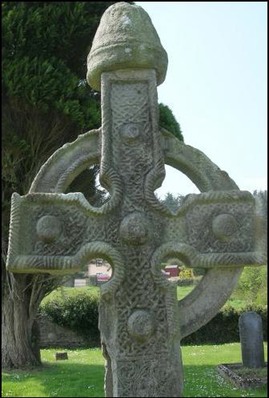

“The two stone crosses actually imitate wooden crosses that were encased in metal plates and are decorated with the type of geometric designs, interlacing and spirals found on contemporary metalwork. Both crosses have unusual bee-hive shaped hats that are only found on a few other crosses.” http://www.culturalheritageireland.ie/index.php/heritage-sites-and-centres/95-the-ahenny-high-crosses-near-carrick-on-suir-co-tipperary

Crawford noted in 1909 that the two crosses at Ahenny are “probably the best specimens in the country of decoration by abstract designs. . . . Almost every variety of Irish carving may be studied at Ahenny.” (Crawford, pp. 258-259)

Edwards identifies several characteristics of the two Ahenny crosses. The heads of the crosses are large and ringed. The shafts of the crosses are short compared to the size of the head. Both have bosses on each face of the cross. The bases are relatively large and in the shape of truncated pyramids. Both crosses have conical caps. There is some debate about the authenticity of the caps, but Edwards offers several reasons to presume they are original. The moulding on each cross has a rope-like quality that derives from metalwork bindings. (Edwards, pp. 6-8)

For additional information on the types of Geometric Design, see the page on this site titled “Geometric Design”, which relies largely on Crawford’s 1926 "Handbook of Carved Ornament: From Irish Monuments of the Christian Period” For a detailed analysis of the geometric designs and figural images on the Ahenny crosses see Nancy Edwards “An Early Group of Crosses from the Kingdom of Ossory.”

The North Cross

The Ahenny North Cross is located in a rural church yard in Co. Tipperary. It is one of two crosses found there. The photos show, on the left the west face of the cross and on the right the east face. The cross stands 8’ (2.46m) high and is 4’6” across the arms. It sits on a stepped base that is 26” high and 31.5” by 24.5” at ground level. Both the North and South crosses are carved of sandstone and probably date from the ninth century, an early period of stone cross making in Ireland.

The cap of the Ahenny North Cross has been interpreted in a number of ways. Porter suggests it is an imitation of the miter of a bishop. Hilary Richardson sees it as connected with the dome shaped church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. Helen Roe wonders if it was an original part of the cross or a later addition. As noted above, Edwards offers reasons to believe the caps were original.

East Face

Peter Harbison describes the east face of the head of the cross, in part, as follows. “The head is formed of a single panel of interlacing in relief with the edges of the cross decorated with the same high-relief rope-moulding which formerly framed the shaft, where it has sadly been largely broken away. There are five decorative bosses — one on each arm and two on the shaft respectively above and below the fifth and largest one, which is at the centre of the head.” (Harbison 1992, 11)

Moving down the shaft of the cross we find a zoomorphic design. Moving out from the center where there are four tightly woven coils, we have in each corner of the panel a spiral design that terminates in its center in three birds’ heads.

At the bottom of the shaft of the cross we have two panels. The upper of the two is composed of a pattern of squares-in-squares. The panel itself is square and there are nine large and many smaller ones within. L-shaped corners surround the nine large squares.

The lower of the two panels is on what is known as the plinth of the cross. In this space we have three interconnected spirals framed by rope-moulding.

West Face

The head of the west face is quite complicated. “The head is covered like a spider’s web with a single panel of intricately-composed coiled spirals (some terminating in three animal heads), C-shaped scrolls back to back and S-spirals. A boss in the centre of the head has interlace on the side and, on top, four curious raised features radiating from the centre which Clavert suggested to be an equal-armed cross. The boss on the shaft beneath it is flat-topped and has interlace decoration. The other bosses — on the arms and on the upper limb — are dome-shaped and bear interlace ornament, arranged in such a way so as to leave a sunken cross-form in the centre.” (Harbison 1992, 13) In this way the theme of crosses within the cross emphasizes the importance of the symbol.

Moving down the cross we have an example of human interlace. There are four human figures, a head in each corner of the panel. The arms and legs are interlaced in a completely unnatural way.

What does this mean? Does it represent the interconnectedness of human community, or perhaps the tangle of human sin for which the cross is God’s response?

“The lowermost panel of the shaft, above the plinth, has a central square of interlacing surrounded by a diagonal fret pattern with vertical bars and interspersed diamond-shaped openings.” (Harbison 1992, 13)

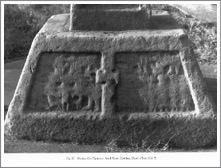

The base of the cross is carved on each side. The photo to the left shows the west face of the base. While interpretations of the scene vary, most scholars see the figure in the center as Christ and the flanking figures as Apostles.

Many have suggested this scene may depict the story of the mission of the twelve told in Mark 6:6-13.

The South Cross

East Face

Base: The base has two panels divided by a flat border that appears as a ringed cross The left panel contains an image of Daniel in the Lions’ Den. The right panel contains a grouping of human figures. This has been identified tentatively as either the Raised Christ or the Mission of the Apostles. Above these figures are two quadrupeds. Their presence cannot be explained. (Harbison, 1992, pp. 13-14 and photos below Vol. 2, Figs. 19 and 22)

Cross:

The shaft is composed of two panels. The lower panel has five coiled spirals. The corner spirals roll into three bird heads. The upper panel has two strand interlacing. The head has five raised bosses. Each has a sunken center. The ring has interlace framed by rope-moulding. (Harbison, 1992, p. 14)

South Side

Base: The base, in its present condition, cannot be interpreted. However, past examinations have revealed hunting scenes. Harbison notes that in the left panel there are two horsemen moving right. It is possible a tree may be behind the right hand horse. The right panel shows a horseman lower right with a quadruped in front and one above it and a dog behind. (Harbison, 1992, p. 14)

Edwards discussed the origin and meaning of hunting scenes. They may well have Christian meaning. The stag was a symbol of Baptism or of Christ Crucified. It played a role in the Psalter which was so important in monastic liturgy. They could also derive from secular models. The Irish had a love for hunting and saw it as part of a noble life. Animals of the hunt were also important in Celtic religion. In addition, Roman hunt scenes may have had an influence. (Edwards, p. 29)

Cross: The shaft of the cross contains three panels, each with C-shaped spirals and a fret pattern and interlace. See the photo to the right.

Ring: The ring contains a meander pattern and interlace.Upper Shaft: The upper shaft has three panels decorated with interlace. See the photo to the left.

Arm end: The end of the arm has a central square that contains five interlinking spirals. See the photo to the right.

West Face

The West Face of the cross can be seen in the photo to the right.

Base: In its present condition nothing can be easily discerned on the west base, seen in the photo below. Earlier examinations revealed a hunt scene in each of the two panels (left and right).

Cross: The rope-type moulding is a prominent feature of the cross, clearly seen in the photos left and right.

The Shaft contains a pattern of “concave interlinked coiled spirals with expanding centres.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 14) See the photo to the left.

The Head has “two-strand interlace terminating in animal-heads which try to devour the bosses.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 14) See the photo to the right.

There are five bosses. The center one is flat topped while the others are conical.

North Side

Base: There is a hunting scene on either side of ringed cross in center. On the left is a horseman with various animals above and behind. On the right are “two horsemen moving towards the centre with a (?) man hunting an animal above or with a dog in front of him.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 15 and photo below Vol. 2, Fig. 27)

Cross: The design on the shaft and ring is similar to that on the south side.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 52 G 4. The crosses are located just to the west of the R697. The site is signposted.

Ardane

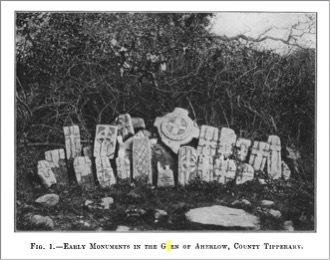

The site at Ardane contains a holy well and a disused graveyard known as St. Berrihert’s Kyle. The photo to the left below appears in 1909 in a paper by Henry Crawford and Steward Macalister. (Crawford and Macalister, facing p. 59) The site has obviously been improved over the years as indicated by the photo on the right. It now consists of a stone wall that circles the area and is lined with various crosses and cross slabs. There are two cross heads of free standing crosses and an apparent cross base below the larger of the cross-heads. The base, not shown, is c. 18” (45 cm) high and 47” (1.20) by 49" (1.25m) at the base.

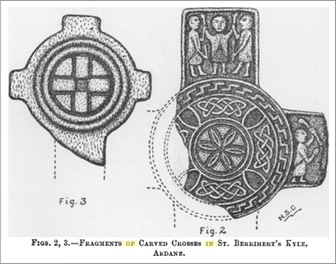

The photo to the right offers sketches by Crawford of the two high cross heads. (Crawford and Macalister, p. 60)

The Larger Cross-Head: This cross-head is 33.5” (85cm) high, 41” (1.04m) across the arms and 6.5+” (17cm) thick. The larger head has a six pointed star in the center. Harbison refers to this design as a marigold pattern. Around this are two circles with design. The inner contains interlace knots, the outer a simple fret pattern. On the top of the cross are three figures, the outer two holding up the arms of the inner figure.

The north or left arm of the cross, not shown in the illustration contains an image that Harbison identifies as the Kiss of Judas. The south arm, pictured in the illustration is tentatively identified as the Mocking or Flagellation of Christ. On the top arm the image may represent the Second Mocking of Christ. (Harbison, 1992, p. 19) This would mean that the figural images on the head all have to do with the passion of Christ. It might be reasonable to assume the images on the lost shaft also had images from the passion.

The other face of the larger cross is also visible. It has a cross in the center of the head that is surrounded by a circle. Harbison identified interlace on the ring and the arms. (Harbison, 1992, p. 19) See the photo to the left.

The smaller cross-head: This fragment is 24.5” (62cm), high, 21” (54cm) across the arms and 4” (10cm) thick. The smaller of the two cross heads contains a Greek Cross with a square depression at the center. It is surrounded by two raised circular mouldings. The back side of this cross is not visible. See the photo to the right.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 51, B 4. This site is not signposted and can be challenging to locate. It lies south of the L3102 west of the N24. The L road can be accessed from the N24 northwest of Caher. Take the L3102 west for about 9km. The best strategy from there is to stop and ask locals. The site is off the road, through a wooden gate, across a field and into the next, see the map to the right. We were fortunate enough to meet the owner of the land, who gave us directions.

Ballynilard Cross

Nothing is known of the history of this site. In 1899, A. P. Morgan published a small article in The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. He noted that near the cross were a socket-stone and a bullaun stone. These are shown in the photo below. There was no record of a burial place there and no trace of any buildings.

Morgan described the cross as 5’7" (1.7m) in height and about 33" (85cm) across at the arms. The shaft is 21” (54cm) wide and 11” (28cm) thick. The cross has a ring that is imperforate. On one side there are five bosses, one on each arm and one in the center. On the reverse there are no bosses. (Morgan, p. 430) Harbison adds that there appears to have been interlace on both faces of the cross. (Harbison, 1992, p. 25)

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 51, A 3. The site is located just north of the R662 or Galbally Road about 2km west of Tipperary town. It lies to the north of the road in the second field back. It is visible from the road if you are going slow enough or are biking or walking. It is just about 500m west from the Leahy’s Furniture & Carpet.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Rock of Cashel Cross

The Monastery

The Rock of Cashel is a large limestone outcrop that rises in a broad and fertile plain. In ancient times and up till 1101 C.E., the Rock was the royal center for the Eoghnacht Chiefs, or Kings, of Munster The name Cashel refers to a circular fort with a stone surrounding wall. In 1101 CE, during a synod held at Cashel, Muirchertach Ua Brian, King at Cashel, gave the rock and surrounding land to the Church in honor of God and Saint Patrick.

At the Synod of Rathbreasail in 1111, the largely monastic organization of the church in Ireland was replaced by the Episcopal system and Cashel became one of two Archdioceses in Ireland, the other being at Armagh in the north.

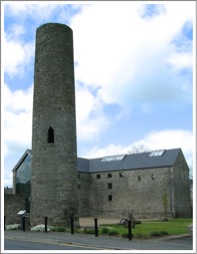

The buildings that now top the Rock of Cashel are from the period of church control. They include the ruins of a cathedral, a chapel, a round tower, and the hall and dormitory of Vicars Choral.

The Cross of St. Patrick stood near the cathedral and was almost certainly carved in the early 12th century. The original is now indoors and a replica stands in the place the cross originally occupied. By making copies and moving the original inside a number of the Irish High Crosses are being preserved for the future.

About the Cross

The Base: The cross of St. Patrick stands on a large stone base not seen in full in these photos. The interesting thing about this base is that legend has it that this stone was used in the crowning of the Kings of Cashel from pre-historic times to the twelfth century.

West Face [right]: Francoise Henry describes the west face. “A very monumental figure of Christ dressed in a long, plain dress reaching to the feet, occupies one side. As H. G. Leask has shown, there may have been small angels carved on separate stones, on both sides of the head of Christ.” (Henry 33) Peter Harbison adds that “on his breast Christ would seem to bear an upright rectangular object (satchel or reliquary?) suspended from around his neck, while beneath the throat there would appear to be a horizontal lozenge-shape, perhaps a brooch.” (Harbison 35) These objects are not readily visible when viewing the cross. If the object is a satchel, it would very likely have been understood to contain the Gospels.

East Face [left]: On the east face of the cross we find the figure of a bishop or abbot. Harbison writes that the figure “raises his right hand in blessing while his left holds a crozier.” (Harbison 34) Traditionally, this figure has been identified as St. Patrick, hence the name for the cross. To my mind, this is almost certainly a bishop as Cashel was the seat of the Archbishop for the southern half of Ireland and was just being established as such at about the time we can presume this cross was carved. In this case it may represent Patrick as bishop of all Ireland, or the office of archbishop in general and the authority of the archbishop of Cashel. It has also been suggested that this figure may represent the founder of the monastery (who may not have been a bishop) or Christ as bishop or abbot of the world. (Harbison 344)

Unique Features: The Cashel cross is unique in that it had vertical stays reaching from the base to the end of each cross arm. Roger Stalley suggests these were structural. (Stalley 44) Françoise Henry suggests these props may represent the crosses of the thieves crucified along side Jesus. (Henry 33) In addition, the Cashel cross, like others from various periods of cross carving does not have a circle around the head.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 51 C 2. The cross is located in the town of Cashel in the monastery there. The site is to the west of the R639 where there is a cluster of red and one white circle.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Emly, Co. Tipperary:

From the Emly Parish Homepage referenced below we find this brief history of the monastery.

“Emly is one of the oldest centres of Christianity in Ireland. We boast that it pre-dates our National Apostle, St. Patrick. Up until the early Middle Ages Emly was the seat of the premier diocese in the south of Ireland.

St. Ailbe is Patron Saint of the Archdiocese of Cashel and Emly. Tradition tells us that he preached Christianity in Munster before the arrival of St. Patrick. He is also associated with the founding of a monastery at Emly. In their book ‘The Parish of Emly’ Michael and Liam O’Dwyer write, ‘Despite the complete obliteration of the layout of the original site we may presume that the monastic enclosure coincided with the present graveyard. The presence of a well and an inscribed cross, both traditionally associated with St. Ailbe, and the fact that successive cathedrals occupied the area near the middle of the graveyard, are sufficient evidence for this assumption.’"

Emly remained a Cathedral city until the 16th century.” (http://www.emly.ie/history/)

The Saint: Both Ailbe and Emly (Imleach lubhair) take their names from the pre-Christian history of the area. Imleach lubhair can be translated “the lakeside of the yew tree”, and there was apparently a sacred yew at this place. Ailbe was the name of a mythical divine warhound that guarded the boundaries of Leinster. The name Ailbe means “living rock”. Tradition states that Ailbe was abandoned as an infant and was found and raised by a she-wolf.

Ailbe may have received the Christian faith from Wales, as there was open communication between Wales and southern Ireland at the time. As an abbot and a bishop, Ailbe wrote a monastic rule for his monks. A couple of examples will speak to the whole. “Let him be steady, let him not be restless, let him be wise, learned, pious; let him be vigilant; let him be a slave; let him be humble kindly. . . . Let him be constant at prayer, his canonical hours let him not forget; his mind let him bow it down without insolence or contention” (http://www.catholicireland.net/saintoftheday/st-ailbe-of-emly-d-528-the-patrick-of-munster/ 12/6/2015)

From the Annals of Ireland we can identify a number of the abbots of Emly. They include: Conamail (d. 708); Celiac (d. 720); Abner (d. 760); Flann (d. 825); Eogan (d. 890); Mescal (d. 899); Flann (d. 904); Tipraite (d. 913); Eochu (elected in 914); Mac Lenna (d. 935); Eochaid (d. 942); Uarach (d. 954); Faelan (d. 980); Tipaite (removed 980); Cetfaid (elected 980); Marcan (elected 990); and Colum Ua Laigenain (elected 995).

The Annals also report other information of interest. Eogan, son of Cenn Faelad, who died in 890, was killed. In 968 the monastery was sacked, it is unclear by whom. Brian Boru took hostages from Emly and other monasteries “as a guarantee of the banishment of robbers and lawless people therefrom.” (Annals of Inisfallen, 987) In 1015 another murder occurred at Emly when “Fiach, son of Dubchron, was treacherously killed by Carran’s son in the middle of Imlech Ibuir (Emly)” (Annals of Inisfallen, 1015)

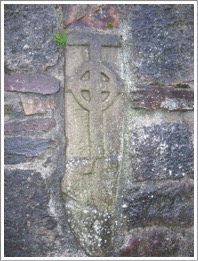

The Cross: The cross is ringed and imperforate. It stands just under 5’ (1.5m) in height. The arms are short, reaching just beyond the ring. The shaft is 16” (40cm) wide. On each face a cross is carved.

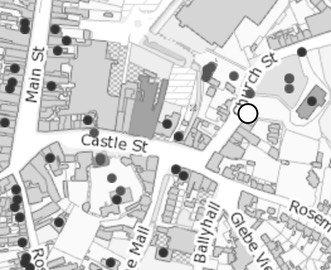

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 50 H 3. The cross is located in the Emly graveyard, toward the back. The cross is marked on the map by the white circle.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Lorrha:

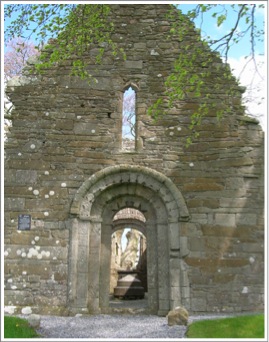

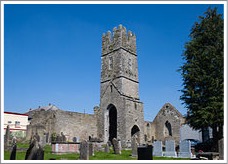

The Site: According to a brief history of Lorrha, a monastery was founded there in the middle of the 6th century by St. Brendan the Navigator. It was soon turned over to St. Ruadhan and Brendan moved west to found the monastery at Clonfert in Co. Galway. There is still some evidence of the ditch or mound that surrounded the monastic settlement. At the site today are the ruins of an 11th century church and the bases and shafts of two high crosses.

During the 9th century the monastery was attacked by the Vikings twice. (Lorrhadorrha)

During the 9th century the monastery was attacked by the Vikings twice. (Lorrhadorrha)

To the left is a photo of the old church building undergoing restoration in 2008. One of the crosses is visible just to the right of the building.

The Saint:

St. Ruadhan was considered to be one of the Twelve Apostles of Ireland. These were twelve saints who studied under St. Finian at the Clonard Abbey in County Meath. His name means “red-haired man”. He is considered the founder of Lorrha, founding it about 550 CE. He reportedly died in about 584 CE. Ruadhan was a member of the royal Eoghanacht clan of Munster. As noted above he was educated by Saint Finian at Clonard, a very famous center of learning.

In the hagiography, he is credited with many miracles. The most significant story about Ruadhan has to do with a conflict with the high king, Diarmaid mac Cearrbheoil. The king seized a hostage from Ruadhan’s sanctuary. As a result Ruadhan cursed him. The two were later reconciled and the hostage was returned in exchange for thirty grey horses. (Ruadhan of Lorthra)

The Lorrha monastery was a place of learning. In the mid 11th century monks there transcribed and annotated The Stowe Missal. This manuscript is a sacramentary rather than a missal and was written mostly in Latin with some Gaelic shortly after 792 CE. It is also known as the Lorrha Missal. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lorrha)

A missal is a liturgical book containing all instructions and texts necessary for the celebration of Mass throughout the year. A sacramentary contains only the priests part of services and includes such words for more than just the mass.

Lorrha appears only a few times in the Annals of Inisfallen.

AI707.2 Colmán, abbot of Lothra, rested.

• AI747a.1 Kl. Repose of Dúngal, abbot of Lothra. The slaying of Aed Dub.

• AI780.1 Kl. Repose of Ailill, abbot of Lothra.

• AI809.1 Kl. Coibdenach the learned, abbot of Lothra, [rested].

• AI1015.10 The vacating of Imlech Ibuir, and the invasion of Lothra. (Lorrha)

The Crosses:

There are partial shafts and bases of two crosses. They seem to date from about 750 CE. Their present broken state may be attributable to the Cromwelligans, who vandalized them during the 17th century. (offalytourism.com)

The Northwest Cross:

Only a small portion, 33” (85cm) of the shaft of this cross remains. The base is quite large, standing 39” (1m) in height. It is 47” by 23.5” (1.2m by 60cm) at the base.

East Face:

East Base: The base is divided horizontally into two registers. The lower register has two parts. The left side of the register takes up about three quarters of the width of the base. It consists of two lion-like animals facing each other, each with a raised paw. Further right is another lion-like animal facing right toward a man with outstretched hand. The meaning is not clear. Noah summoning the animals into the Ark and Daniel in the Lions’ Den have been suggested. On the far right of the lower register Harbison identified two crosses, each with a hole in the square at the crossing. Photo to the left. (Harbison, 1992, p. 137 and photo Vol. 2, Fig. 457) In my photo much of the lower portion of the base has been obscured by a grave marker (photo above right).

The upper register of the base consists of several panels of fretwork. Above that is a narrow step that has a procession of animals moving from the right to the left. On the steps above that no decoration can be discerned.

East Shaft: The shaft contains figure sculpture, with at least two figures visible. No interpretation can be ventured

South Side:

Base: The lower part of the shaft is divided vertically into two panels. The left panel has a scene carved on it. Harbison identifies what looks like an altar with faggots on it in the lower right corner. On the left side there is an indication of a tree. The panel could represent both Adam and Eve in the garden and the Sacrifice of Isaac.

The right panel contains interlace. Above, on a narrow step there are animals moving from right to left. This repeats the pattern on the east face. No carving is visible on the upper steps.

Shaft: What remains is a very worn panel of interlace. (Harbison, 1992, p. 137)

West Face:

The Base: The lowest step of the base is divided into three panels. On the left is interlace, in the center a spiral decoration and on the right a panel of fretwork. The next step up has a procession of animals. The upper steps have no visible decoration.

The Shaft: There appears to be figure sculpture, but no interpretation can be offered. (Harbison, 1992, p. 137)

North Side:

North Base: The lowest step is divided vertically into two panels. A bit of fretwork is visible on the extreme right of the right panel. Otherwise the panels are badly worn. On the next two steps up is a procession of animals.

North Shaft: Interlace is visible in the central panel of the that fragment. (Harbison, 1992, p. 137)

Southeast Cross

The base of this cross is 61” (1.55m) square and about 21.5” (55cm) in height. The shaft measures 19” by 17” (48 by 43cm). It is rough-hewn in its present condition. Harbison noted that on the north side of the base there is possible Daniel in the Lions’ Den image. The upper part of this image has been broken away.

The shaft measures 19” by 17” (48 by 43cm). Each side appears to contain interlace. It measures 19” by 17” (48cm by 43cm) at the base. “A panel in the middle of the east face would appear to bear the representation of a horseman bearing a crook.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 138)

Photos are:

Above left: East Face; Above right West Face

To the left: North side; To the right South Side

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 43 B 1. Lorrha will be signposted off the R489 between Portumna and Birr.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Mona Incha:

The Monastary and Saints

Information on the history of Mona Incha can be difficult to unravel. The best source seems to be the research in the late 19th century by Canon O’Hanlon. He produced Lives of the Irish Saints.

The photo to the left shows the entire area of the Mona Incha site. It is a very small area. It was originally an island in a shallow lake.

O’Hanlon's research revealed the following. In the late 6th or early 7th century Saint Cronan, founder of the monastery at Roscrea, to the west of Mona Incha, built a cell on the island. Presumably he used this as a place of retreat. The Roscrea monastery was established in the late 6th century, placing the early religious use of Mona Incha to that same period of time.

The photo to the right shows the west front of the church at Mona Incha with the Romanesque arch.

Some two hundred years later, Saint Elair (Helair) appears on the scene. He is described as “Patron, Anchoret and Scribe of Mona Incha near Roscrea, County Tipperary.” O’Hanlon assigns Elair to the 8th and 9th centuries. He writes, “The death of this Elarius, Anchoret and Scribe, of Lough Crea, is entered in the Annals of the Four Masters, at 802; in those of Clonmacnoise, at 804; in those of Ulster, at 806; but, as we are told by Dr. O’Donovan, it should be 807.” O’Hanlon suggests Elair may have been part of the Culdee movement and refers to his “life of strict observance and asceticism.” (omniumsanctorumhiberniae.blogspot.com)

In 1140 the Augustinians founded an Abbey at Mona Incha and dedicated it to Saint Mary. They had a presence there until 1485. It was during the 12th century the church that remains on the site as a ruin, was built. In the mid 13th century new windows were added to the east wall of the chancel and the south wall of the nave. (thestandingstone.ie)

One legend connected to the site states that any woman attempting to visit the island would die instantly. In contrast any man, while on the island, could not die.

Mona Incha has been given several names. The Standing Stone website refers to it as Inis na mBeo’ or “Island of the living.” The Irish Stones website names it Moin na hinge or “the island in the bog.” The Journal website has the name as Mainistir Inse na mBeo or “the Monastery of the Island of the Living.”

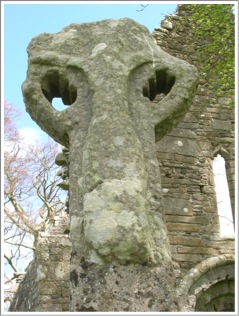

The Cross

The Mona Incha cross consists of a base and head joined together by a modern concrete shaft. The Irish Stones website suggests a date for the base in the 9th century and for the head in the 12th century. Peter Harbison suggests the two are likely contemporary, both being carved in the 12th century. (irishstones.org; Harbison, 1992, p. 139)

The photo to the left shows the east side of the cross.

The Base

The base stands 17” (43cm) in height and measures 33.5 by 27.5” (85 by 70cm) at ground level.

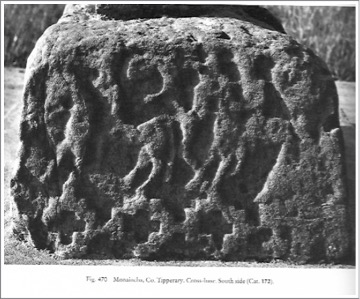

The east face and north side of the base have no decoration. The south side has an image of two horsemen. Between them there is a large figure that may have been speared by the rider on the right. The horses stand on stepped crosses. It has been suggested that this image may reflect the Exodus. The west face of the base has figural sculpture that can no longer be identified. (Harbison, 1992, p. 139)

The photo below shows the south side of the base. (Harbison, 1992, vol. 2, figure 470)

Upper Shaft and Head

The shaft/head segment is 36.5” (93cm) in height and measures 24” (61cm) across the arms. The shaft is 11.5” (29cm) wide and 8” (20cm) thick.

The east face of the head, as seen above, bears animal interlace but it is badly worn. The west face, seen in the photo to the right, bears an image of Christ crucified.

The north and south sides both contain animal interlace, also badly worn. “The top of the north side of the shaft has a fragmentary panel bearing the heads of two unidentified figures.” This is illustrated in the photo to the left, at the bottom of the picture. (Harbison, 1992, p. 139 and vol. 2, figure 469)

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 43 D 3. The site is marked on the map. From the traffic circle on the east side of Roscrea along the N62 take the exit that goes to the southeast, stay left at the fork in the road and the site will be signposted.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Roscrea: County Tipperary

The Monastery and Community

We have the following description of the town of Roscrea, published in the Dublin Penny Journal in 1834, and signed with a simple “B”.

“On my way from Birr I arrived at the summit of a hill, between Drumakeenan and Roscrea, which overlooks the later place. The view from thence struck me with awful recollections of by-gone times. The aged round tower and saxon gable end of St. Cronan’s abbey on the left, and the venerable steeple of the Franciscan monastery on the right, presented on both extremities of the view objects claiming the attention of the antiquary and traveller while the middle space was diversified by the ruins of a round castle of King John’s time, and those of a less ancient one of the days of Henry the Eighth. In the distance, reviving the long dormant spirit of Irish chivalry, appeared Carrickhill, anglice, the Hill of the Rock, from which is taken the title of the Earl of Carrick. The modern church and steeple, and Roman Catholic chapel exhibited a neat but humble contrast to — as they were placed by the sides of — their respective venerable neighbours, the ecclesiastical ruins first mentioned.” (Dublin Penny Journal, p. 268)

This description could be used as a tour guide of significant sites in Roscrea in the early twenty-first century. The photos below show some of these sites. Clockwise from the upper left: Roscrea Round Tower, West Gable of the 12th century Romanesque church (photos by author), Gate Tower of Roscrea Castle and ruins of the Franciscan Friary. (wikipedia.org/wiki/Roscrea).

Roscrea is located in a gap in the hills along the ancient road known as the Slighe Dala.

The Saint

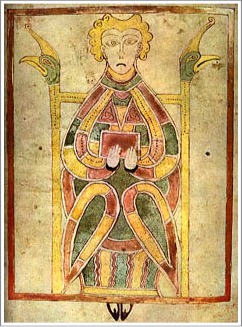

Saint Cronan was the Abbot-Bishop and patron of the monastery at Roscrea. He had been living in Connacht but returned to his native area about 610 C.E. He initially settled at what is now Mona Incha, as described above. He seems to have had a cell there. Soon after, perhaps in 610, he founded the Abbey at Roscrea. He established a school there of some repute. Across the years the Abbey produced at least three books: the Book of Dimma which dates to the 8th century, the Annals of Roscrea, and the Rule of Echtgus Ua Cuanain (a tract on the Eucharist) that dates to the 12th century. (encyclopedia.com) The image to the left is the carpet page for the Gospel of Mark in the Book of Dimma, showing the Evangelist Mark. (http://art-imagery.com/book.php?id=dimma)

The Cross:

The cross is carved of sandstone and is in two sections, joined by a concrete piece that forms the upper shaft. It stands on a low base that has no carving. The shaft fragment stands 5’10” (1.78m) tall and is 31.5” (80cm) wide and 16” (40cm) thick. The head fragment is 47” (1.20m) in height and 59” (1.5m) across the arms.

East Face: (pictured to the right)

Shaft: The east face has four panels.

E 1: Adam and Eve, apparently clothed and standing beside a tree.

E 2 and 3: These panels up are badly eroded, and somewhat difficult to distinguish, but seem to have animal interlace.

E 4: This panel, also difficult to define, has a figure that may be a centaur. There are two figures behind. One of them may be playing a Pan pipe.

The image above left depicts the east face and south side of the cross. (Harbison, 1992, vol. 2, Figs. 541, 142)

Head: The head has a large image of a Bishop or Abbot who holds a crozier in front of himself. (See photo to the right.)

South Side

Shaft: There is an image of a bishop or abbot on the shaft. This figure wears a cloak and holds an in-turned crook in the right hand. (See image above right.)

Head: The majority of the south side of the head is a substitute. At the very top of the head of the shaft, part of the original, there appear to be two human figures.

West Face

Shaft: The shaft on this face of the cross is badly worn. It has been identified in the past as having several panels of animal interlace.

Head: The head has an image of the crucifixion. Harbison describes the image as follows: "Christ, probably bearded and with his hair falling down onto his shoulders, stretches out his emaciated long arms, that on the right being a modern replacement. He is apparently clad in a long robe with a belt at the waist.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 163)

The photo at the left shows the upper shaft and the head of the west face.

North Side

North Side

Shaft: There is a large human figure, wearing a long robe that is belted at the waist. The belt-ends can be seen hanging down the front of the figure. The head is missing and was apparently originally separate.

The photo at the right shows the west face on the left and the north side of the shaft on the right. (Harbison, 1992, vol. 2, Figs 543, 544)

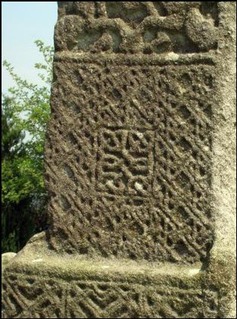

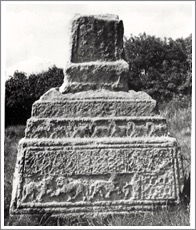

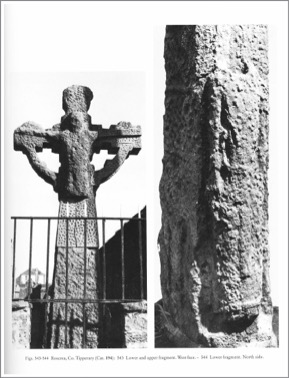

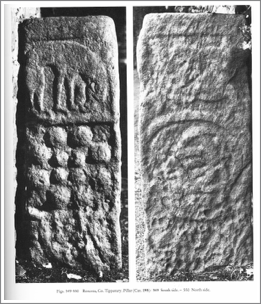

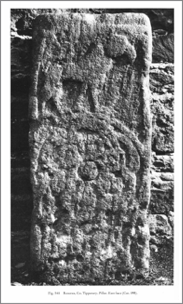

The Pillar: (Photos from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Figs. 248-50)

A pillar, measuring 35.5” (90cm) above ground and 17” by 14” (43cm by 36cm), stands near the Catholic Church. It’s provenance is unknown. It was moved to its present site in 1938. It is possible that it was originally part of a cross.

East Face: Harbison identifies three panels on this face of the cross, pictured to the right.

E 1: “On the bottom of the east face three figures seem to hold up sticks or spears and advance to the right towards a (?) seated figure, behind whom there may be another figure. The (?) seated figure seems to grasp at the stick of the foremost standing figure which projects upwards to the panel above where it crosses what seems to be an animal figure, and where it has an unusual boss on top of it. The worn nature of the sculpture makes interpretation hazardous, though it could conceivably represent David Presenting to Saul the Head of Goliath on a stick.” (Harbison, 1992, pp. 163-4)

E 2: In the center of the shaft is a scene that may represent Daniel in the Lions’ Den. It centers around what appears to be a boss, but is actually a human head.

E 3: On the top is a griffin, it may hold two legs in its mouth. (Harbison, 1992, p. 164)

North Side:

N 1: At the bottom of the shaft is what appears to be a hunting scene.

N 2: Above it is what appears to be "an animal interlace enclosed by a raised circular moulding.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 164)

N 3: At the top is a quadruped that may be a winged griffin. See the image on the right in the photo above on the left above).

South Side:

S 1: “A figure on the left may ride on a quadruped, and there may be a figure behind a (?) tree and two further figures in front.” Harbison notes that this might represent the Entry of Christ into Jerusalem. (Harbison, 1992, p. 164)

S 2: In the center is a pattern of bosses. There are four bosses in the center surrounded by a ring of larger bosses.

S 3: At the top of the shaft is a quadruped with an arched body. See the image on the left in the photo above to the left.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 43 D 2/3. Located in central Roscrea along Church Street.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Toureen Peakaun

The Monastery

The monastery that became Toureen Peakaun was founded in the seventh century by St. Alban or Abhun. His successor was St. Beccan (also referred to as Peakaun, Beagan and Mo-Bhec-oc). It was from this St. Beccan that the name of the site derives. There is a scarcity of information about the history of the site. The features of Toureen Peakaun lie on either side of the small stream in the photo to the left. The road is just wide enough for one vehicle.

The monastery that became Toureen Peakaun was founded in the seventh century by St. Alban or Abhun. His successor was St. Beccan (also referred to as Peakaun, Beagan and Mo-Bhec-oc). It was from this St. Beccan that the name of the site derives. There is a scarcity of information about the history of the site. The features of Toureen Peakaun lie on either side of the small stream in the photo to the left. The road is just wide enough for one vehicle.

A beginning date in the 7th century is suggested by the tradition regarding the foundation of the monastery. Harbison suggests that the inscription on the East Cross, which bears letters similar to those used on the Armagh chalice may date to the eighth or “at latest to the first half of the ninth century.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 379) The presence of a twelfth century church at the site suggests a continuation of the monastery during that time. The presence of the West cross, a cross that is not early and seems to postdate the twelfth century, suggests the monastery was still active in the thirteenth century. We can deduce then that the monastery was active during a period of at least six hundred years, from some time in the seventh century till some time in the thirteenth century. The photo below shows the church with remains of the East Cross in the rectangular area in the left foreground.

The Saints

Saint Alban (Abhun, Abban):

The primary information available regarding St. Alban relates to his foundation of the monastery at Toureen Peakaun. Canon O’Hanlon states that Alban established a “great and most regular monastery” known as Cluain-aird-Mobhegoc or Mobecoc. Tradition suggests that at some point after founding the monastery he moved on and left the monastery in the care of St. Becan.

(http://omniumsanctorumhiberniae.blogspot.com/search/label/Saints%20of%20Tipperary )

Saint Becan (Beccan, Peakaun, Beagan, Mo-Bhec-oc):

In a helpful article on her omniumsanctorumhiberniae blog, Marcella helps clarify who Saint Becan of Toureen Peakaun was. In the literature on the Irish saints there are three Becans whose lives seem to be confused and conflated. One of these saints is connected with Saint Alban; another with St. Colum-Cille and the third with King Diarmaid. (http://omniumsanctorumhiberniae.blogspot.com/search/label/Saints%20of%20Tipperary) Making use of Canon O’Hanlon’s Lives of the Irish Saints, Marcella’s blog offers the following bits of information about this second abbot of Toureen Peakaun.

O’Hanlon dates the life of Becan to the sixth century, believing he was a contemporary of Colum-Cille and King Diarmaid. This would contradict the tradition stated above that the Toureen Peakaun monastery was not founded until the seventh century. In O’Hanlon’s entry, however, it is often difficult to determine which of the three Becans listed above he is referring to. He later refers to a death date for Becan of 687 C.E./A.D. This would be consistent with a seventh century date for the foundation of the monastery.

Becan was reputed to be a recluse or hermit. It is reported that he often fasted for as many as three days. He lived a penitential life, constantly praying on bended knee for forgiveness of his many imperfections. It is said he had a stone cross erected in the open and that regardless of the weather he would each day stand by the cross, with arms outstretched as if hanging on the cross while he recited the whole of the Psalter

The Site

There are numerous features at the Toureen Peakaun site. The most obvious is the twelfth century church pictured above. The church is about 36 feet by 24 feet. Fastened to the walls of the church are two undecorated stone crosses and the remains of a sundial. See the photos below.

In addition, there are two cross inscribed slabs attached to the walls of the church. These are pictured left and right. The source of these photographs is the Early Christian Ireland website cited below.

Across the stream that bisects the site and some distance away are St. Peacaun’s Well and Peacaun’s Cell (presumed to have been a small beehive hut). See the photos left and right.

To the west of the church, on higher ground is an undecorated stone shaft that is presumed to be the shaft of a cross. It is referred to as the West Cross. See the photo to the left.

Southeast of the church there is a rectangular area where numerous stones have been placed. See the photo to the right.

These include parts of the East Cross, two cross inscribed stones and remains of grave slabs. See the photo above right and those to the left and right. The source of the photographs of the cross inscribed stones is the Early Christian Ireland website cited below.

The Crosses

As indicated above, there are four crosses or, more accurately, fragments of crosses present at Toureen Peakaun. Harbison lists only one, the East Cross, as fitting his criteria for Irish High Crosses. This suggests that the other three, the West Cross and the two plain crosses attached to the walls of the church are of a date later than 1200. I will be describing each of the four crosses, beginning with the East Cross.

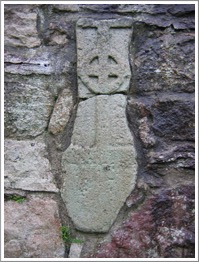

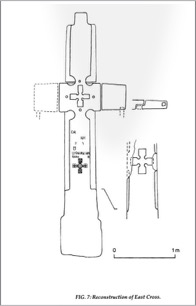

The East Cross:  The East Cross is a composite cross. In this case several pieces were hinged together to form the cross. Waddell and Holland refer to it as a “joiner’s cross”. In describing it they wrote that the cross “measured (13’4”) 4.06m in total length, (10’2”) 3.10m in length from the shoulder of the foot to the top of the top tenon. It was (29”) 73.5cm wide at the foot, (21”) 54cm at the lower shaft, and tapered to about (17”) 43cm; thickness was about (9”) 23cm. The shaft was rebated, and this rebate extended inwards at the junction of shaft and arm to form hollowed angles.” (Waddell and Holland, p. 175, the illustration to the right is their Fig. 7)

The East Cross is a composite cross. In this case several pieces were hinged together to form the cross. Waddell and Holland refer to it as a “joiner’s cross”. In describing it they wrote that the cross “measured (13’4”) 4.06m in total length, (10’2”) 3.10m in length from the shoulder of the foot to the top of the top tenon. It was (29”) 73.5cm wide at the foot, (21”) 54cm at the lower shaft, and tapered to about (17”) 43cm; thickness was about (9”) 23cm. The shaft was rebated, and this rebate extended inwards at the junction of shaft and arm to form hollowed angles.” (Waddell and Holland, p. 175, the illustration to the right is their Fig. 7)

The term “rebated” refers to a recess cut in the stone to take the edge of another stone that is to be attached to it. As illustrated to the right this was the way that a number of pieces were joined to form the cross. The original was, as described by Duignan, composed of the tapering shaft of micaceous sandstone, the arms of yellow sandstone, with the whole topped by a finial. In the one arm that was found, there is a mortise on the underside which probably accepted a prop that supported the arm. As such, the East cross may have served as a prototype for the 12th century St. Patrick’s Cross on the Rock of Cashel where each arm was originally supported by a prop or crutch. (Waddell and Holland, p. 175)

Both the shaft and the arm share the feature of a reveal. This appears on each face of the cross as seen in the photos below. In the photo to the left the tall stone is part of the shaft of the cross. In the foreground and just to the right is a stone that is one of the arms of the cross.

The east of the cross, illustrated in the left photo, bears an incised cross, ringless and with short square-ended arms. (Harbison, 1992, p. 174)

The west face is more complex. It is the side shown above in the illustration from Waddell and Holland and in the photo to the right. There is an “incised cross pattern at the crossing and with it an arrangement of four small circular sockets in the face of the cross just beyond the end of each arm of the cross pattern” It is speculated that these sockets received ornamental bosses. (Waddell and Holland, p. 179)

Lower on the shaft is another incised cross and above it “a six-line inscription in a mixture of capitals and half uncials. This mixture of scripts led Duignan to “suggest an early date ‘before the half uncial had been established as the Irish norm for inscriptions as well as for manuscripts.’” (Waddell and Holland, p. 179) The inscription has yet to be deciphered.

The West Cross:This is not listed by Harbison as a pre twelfth century cross. This was confirmed by Crawford, who in 1909, stated that it was uncarved and not of an early type. The cross is composed of two fragments that stand on a platform above the church to the west. Duigan noted some “very faint lines on the pitted West face of this shaft are a very uncertain cross pattern.” (Waddell and Holland, p. 179) Both faces are pictured left and right.

Two Plain Crosses:

These crosses are both rectangular in design. Each has a small tenon that would accommodate a cap. Each also has a small hole near the center of the crossing. The cross to the left has a mortise for a missing arm. The cross to the right has a broken arm. “It is not clear if the upper and lower parts of both of these crosses are joined by a mortise and tenon.” (Waddell and Holland, p. 179)

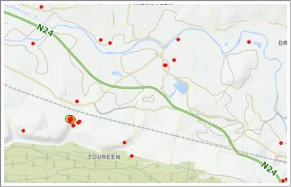

Getting : The site is located between Cahir and Tipperary. From the N24, take the L3102 to the southwest. About half a kilometer along the L3102 take an unnamed road to the south. Within a couple of hundred feet you will cross a railroad track, drive through a farm yard and continue down a narrow lane that runs along a small stream. The cross is on the right near the ruined church. The site is indicated by the yellow circle in the lower left corner of the map below left.

The map to the left is a screen shot from http://webgis.archaeology.ie/NationalMonuments/FlexViewer/

In the search select Tipperary South and search for Cross. 12/10/2015.

References cited:

Annals of Inisfallen, (http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/T100004/index.html)

B., “Roscrea”, The Dublin Penny Journal, Vol. 2, No. 86, February 22, 1834, pp. 268-270

Buckley, Michael J. C., “Notes on Boundary Crosses”, The Journal of the royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 10, No. 3, September 30, 1900, pp. 247-252.

Crawford, Henry S., “The Crosses of Kilkieran and Ahenny”, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 39, No. 3, (Sep. 30, 1909), pp. 256-260

Early Christian Ireland: http://www.earlychristianireland.net/Counties/tipperary/toureen_peckaun/

Edwards, Nancy, “An Early Group of Crosses from the Kingdom of Ossory”, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 113 (1983), pp. 5-46.

Emly: http://www.emly.ie/history/

Encyclopedia.com, www.encyclopedia,com/article-1G2-3407709687/roscrea-abbey.

Harbison, Peter; The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey, Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Henry, Francoise; Irish High Crosses, Three Candles LTD., Dublin, 1964.

Irish Stones: www.irishstones.org/place.aspx?p=234&i=2.

Johnston, Elva, “Munster, Saints of (act. c. 450-c.700)”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford Press, 2004.

MacNamara, George, U., “The Ancient stone Crosses of Ui-Fearmaic, County Clare: Part I", The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 9, No. 3, September 30, 1899, pp. 244-255.

Meehan, Cary, Sacred Ireland,Gothic Image Publications, Somerset, England, 2004.

Morgan, A. P., Ballynilard Cross, The Journal of the royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 9, No. 4 (Dec. 31, 1899), p. 430.

O’Farrell, Fergus, “Dysert O’Dea: The Monks of Dysert O’Dea”, Archaeology Ireland, Vol. 18, No. 3 (Autumn, 2004), pp. 26-27.

Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae: http://omniumsanctorumhiberniae.blogspot.com

Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae: http://omniumsanctorumhiberniae.blogspot.com/search/label/Saints%20of%20Tipperary

The Standing Stone: http://www.thestandingstone.ie/2009/09/monaincha-abbey-and-high-cross-co.html

Tripartite Life, The Confession of St. Patrick; Epistle to . . . Coroticus; Tripartite Life, Aziloth Books, 2012.

Waddell, J. and Holland, P., "The Pekaun Site: Duignan's 1944 investigations", Tipperary Historical Journal, 1990, 165-86. https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/33536138/the-pekaun-site-duignans-1944-investigation-tipperary-libraries/3, 12/5/2015