The Time Period of the High Crosses

How do you know if a free standing stone cross is an “Irish High Cross”? Based on artistic considerations, scholars have typically agreed that the period of the Irish High Crosses was the 8th through the 12th centuries. But how do you date a stone carving? This can be a difficult problem even for the best Irish High Cross scholars. Here’s the problem.

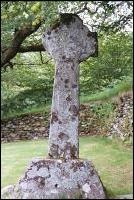

Knowing the physical characteristics of the Irish High Cross (with all of the variety we have seen above) will not guarantee a confident identification of an authentic Irish High Cross. Cemeteries surround the ruined buildings of many of the ancient Irish monasteries, and many of the grave markers look like the ancient Irish High Crosses (some of these are several centuries old, some as recent as yesterday). Clonmacnois in County Offlay offers one example. The three visible crosses in the photo to the left are all in the style of the Irish High Crosses but are not Irish High Crosses. They are more recent grave markers.

Adding to the problem of identifying Irish High Crosses is the fact that not all scholarly lists of High Crosses are identical. The most complete listing is that of Dr. Peter Harbison, High Crosses of Ireland (1992). This is a monumental three volume work that addresses nearly every aspect of High Cross scholarship and has an impressive number of photographic plates. One example of the variation in lists will suffice. Richardson and Scarry in their book, An Introduction to Irish High Crosses (1990), list only one High Cross related to the monastic sites at Glendalough in County Wicklow. Harbison, on the other hand, tells us that Glendalough has more crosses than any other site in the country. In his text, however, he discusses only the three most notable examples. The National Monument Service (http://webgis.archaeology.ie/NationalMonuments/FlexViewer/) lists three additional crosses at the site. There are many other crudely carved crosses at the site that may also have been carved before 1200. Thus, while visiting a site, you may miss a cross because it is not on the list you are working from.

The six crosses, at Glendalough, identified by the National Monument Service are shown below. In the first tier are the crosses listed by Peter Harbison. First tier: The Brookagh or Market Cross in the Visitor’s Centre; the Sevenchurches or Camaderry Cross in the Monastic City near the Cathedral and the Lugduff or Ballinacor South Cross located near St. Reefert’s Church near the upper lake. Second tier: Sevenchurches or Camaderry Cross located near the Priest’s House in the Monastic City; Sevenchurches or Camaderry Cross-head located inside Kevin’s Kitchen on the edge of the Monastic City and the Brookagh Cross located in the Visitor’s Centre.

Dating the High Crosses

Peter Harbison, in his book The High Crosses of Ireland identifies two major categories of crosses, in terms of date carved. There is an early group and a 12th century group. Within the earlier group are several additional groupings of crosses based on geographic and other similarities. For the purpose of exploring issues related to dating the crosses, I have chosen to focus on one of these earlier groupings, the Midland and North Leinster Group. The most important crosses in this group are those from Monasterboice, Kells, Duleek, Durrow and the Cross of the Scriptures at Clonmacnois. To keep this discussion relatively brief I have chosen to rely almost completely on the work of Peter Harbison. (Harbison 1992, p 367 ff)

Overview

In general, there are three factors that might indicate a date for the erection of a particular cross. The first is the presence of an inscription bearing a name that can be located in the timeline of history. As many crosses either do not have inscriptions or have only partially discernable inscriptions this method of dating is at best limited to a small group of crosses. Another limitation of inscriptions is that any particular name may refer to more than one individual in the historic record.

The second method of dating a High Cross involves an analysis of the iconography of the cross. This is the field of the art historian and involves comparison of themes and artistic style with art from mainland Europe and placing the piece in its historic context.

The third method of dating a High Cross involves a study of the history of the site. The majority of the High Crosses are located or were originally located at a monastic site. The history of some of these are well documented while the history of others is shrouded by a lack of information.

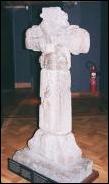

Above is the Cross of Muirdach, Monasterboice, County Louth, east face. It is one of the Midland and North Leinster Group.

Inscriptions

Inscriptions

The Cross of Muiredach [right] has an inscription on the lowest part of the shaft on the west face. The inscription, reproduced below, is carved around the figures of two cats. It is the only cross in the Midlands and North Leinster group to have a complete name in the inscription. The name is Muiredach. This is still not decisive for dating purposes, however. We know of two Muiredachs who were abbot at Monasterboice. One died in 844 and the other in 922. As Peter Harbison points out, there could, of course, be another Muiredach we don’t know about. (Harbison 1992, p 367) Still, the inscription, if properly understood to refer to one of these two abbots narrows the probable dating to a period of about 100 years.

OR DO MUIREDACH LAS NDERN(A)D (I)

CRO(SSA)

Prayer for Muiredach who had the cross erected

Hints from the inscriptions on the crosses at Durrow and the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois tend to confirm that there are two likely periods for the erection of these crosses — “one in the second and third quarters of the ninth century, and the other in the first half of the tenth.” (Harbison 1992, p 368)

Iconography

One important step in attempting to date the High Crosses through the use of iconography is to seek parallels from the continent. Harbison believes the best sources for these comparisons come from “frescoes, mosaics, manuscripts and metalwork.” (Harbison 1992, p 369)

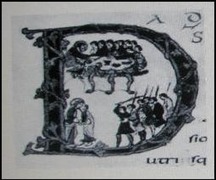

For example, the illustration [left] is an image of the Kiss of Judas on the night of Jesus’ betrayal. It is copied from Harbison 1992, vol. 3, figure 860. The image is from the Stuttgart Psalter, folio 8 recto dated to the late 820’s. This image is seen as comparable to the image of the Kiss of Judas on the Tall Cross at Monasterboice, the west face, the south arm (below left).

The same scene, with a somewhat different composition can be seen on the south base of the Cross of the Scriptures at Clonmacnois (below center). This scene, Harbison sees as comparable to the lower scene in the image (below right) copied from Harbison 1992, vol. 3, figure 861. This is from the Sacramentary of Drogo folio 44 verso done between 830 and 855. the upper scene in the initial letter “D” is a representation of the Lord’s Supper. In both cases there are a number of soldiers.

Above left: Tall Cross, Monasterboice, west face, south arm; center: Cross of the Scriptures, Clonmacnois, south base; [Photo from Harbison 1992], right: Sacramentary of Drogo, folio 44 verso, ca 830-855.CE. [Photo from Harbison 1992].

Historical Context

Theological arguments can assist in setting the historical context of the High Crosses. For much of the 8th and the first half of the 9th centuries there was a movement in the church to restrict the use of biblical images or the images of saints. The fear was that people were worshiping the images and not God. There were two main periods of this so-called Iconoclastic Controversy: 730-787 and 813-843. (McGinn, p 388)

This is relevant to the dating of the crosses because at the Council of Paris in 825, a council of the whole church, the restriction on the use of images was loosened. After 877 and the death of Charles the Bald, Holy Roman emperor, the use of biblical representations almost disappears for about 100 years. However, between these dates Louis the Pious, Holy Roman emperor 813-840 was friendly to the use of biblical images in art. This strongly suggests that the Midlands and North Leinster group of crosses were in the process of development during the second and third quarters of the 9th century.

An additional factor in dating the crosses to this period is the writing of the theologian Paschasius Radbertus. Between 831 and 833 he wrote an influential work on The Body and Blood of the Lord. Which, in an interesting way, brings us back to the crosses of the Midlands and Northern Leinster group. Harbison believes the Broken Cross at Kells may have been strongly influenced by the theology of Radbertus (see below).

Kells, Co Meath, Broken Cross: An Example

In discussing the Broken Cross at Kells [below left west face, below right east face], Harbison makes a strong claim for a connection between the writings of Paschasius Radbertus and the images found on this cross. Passages of scripture Radbertus refers to in his book The Body and Blood of the Lord “can be seen to be so close to the selection of scenes on the Broken Cross at Kells that it could be claimed that the Kells cross is a veritable illustration of Paschasius’ treatise, which stresses so strongly the connection between baptism and the Eucharist.” (Harbison 1992, p 336)

If Harbison’s assertion is correct, it creates another link between the second and third quarters of the 9th century and the development of the High Crosses of this group.

Here is some of the evidence Harbison cites. One: On the west face of the cross, which contains scenes from the Hebrew scriptures there is an image of the Nile River being turned to blood [left]. The text is found in Exodus 7:14-25. From left to right we have Moses, Aaron with the staff of Moses, Pharaoh holding a rod and at least one guard behind him. In the lower center are the heads of two of Pharaoh’s servants. (Harbison, 1992, p 103) This can be interpreted as the wine of the Eucharist becoming the blood of Christ.

Two: There is also an image of the Hebrew people Crossing the Red Sea [right]. This text comes from Exodus chapter 14. At the bottom of this broken panel are waves, presumably the Red Sea. Harbison discerns legs in the water at the center and left. This can be interpreted as the Egyptians being drowned as the Hebrews have reached the other side of the sea. (Harbison 1992, p 103) This has been interpreted as a sign in the Hebrew scriptures of baptism, the people passing through the waters and in essence becoming a new people.

Two: There is also an image of the Hebrew people Crossing the Red Sea [right]. This text comes from Exodus chapter 14. At the bottom of this broken panel are waves, presumably the Red Sea. Harbison discerns legs in the water at the center and left. This can be interpreted as the Egyptians being drowned as the Hebrews have reached the other side of the sea. (Harbison 1992, p 103) This has been interpreted as a sign in the Hebrew scriptures of baptism, the people passing through the waters and in essence becoming a new people.

Three: On the east face of the cross there is an image of the Wedding at Cana, from the Christian scriptures [left]. The text telling the story of the Wedding at Cana can be found in John 2:1-11. Jesus on the left faces the master of the feast who is seated. Behind the master are three or four servants, one of whom is pouring water into the jars at the bottom. Three guests look on. (Harbison, 1992, p 101) Here we have a miracle of water that becomes wine. This has been interpreted as a Eucharistic image.

The dating of the Irish High Crosses is not a precise science. Many factors are considered by scholars in their attempt to suggest appropriate dates. There is and will probably always be disagreements about the dating of many of the crosses.

Where are the High Crosses?

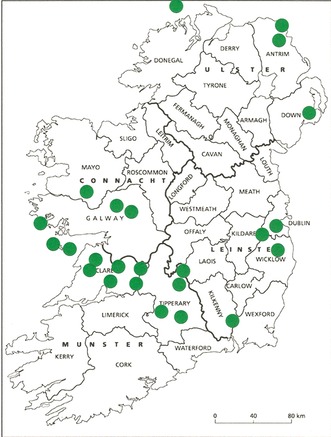

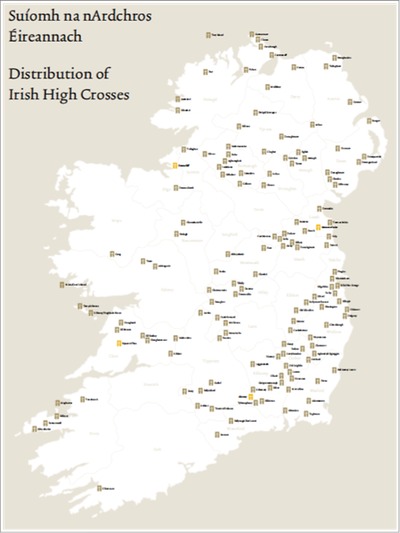

There are at least 250 Irish High Crosses and fragments of crosses around Ireland. It is impossible to know how many of these crosses once graced the landscape of the Emerald Isle. (The map below was found at http://www.museum.ie/en/exhibition/info/the-museum-search.aspx, January 2014.) Each small rectangle with a cross inside indicates the general location of one or more Irish High Crosses. These represent a significant number of the High Crosses in Ireland. While it is impossible to read the names of the sites due to the poor quality of this copy and the smallness of the print on the original map, it does offer a sense of the distribution of the High Crosses.

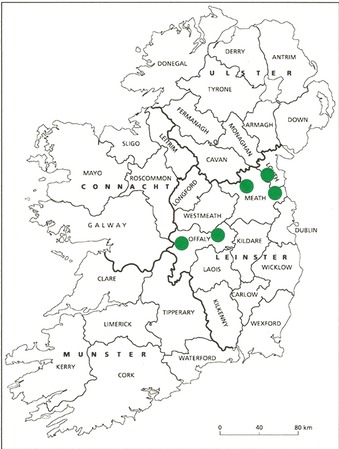

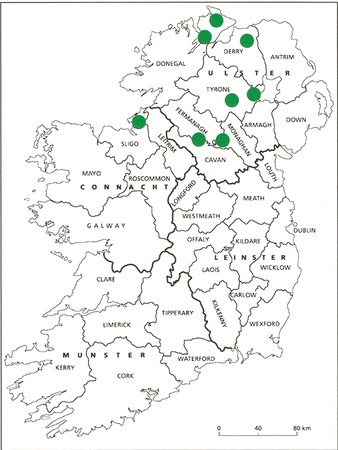

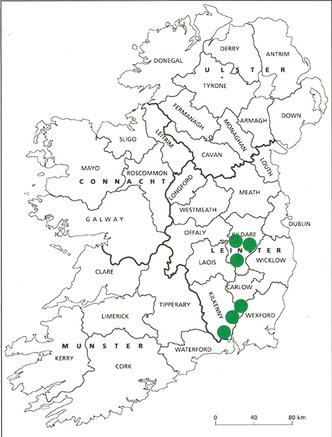

In his chapter on “Dating” the crosses in his study The High Crosses of Ireland, Peter Harbison identifies six geographic groupings of early crosses. These groupings are particularly based on the crosses with carvings representing scripture. The groups are: the Ulster group; the Midlands and North Leinster group; the Bealin-Banagher group; the South Leinster group; the Tipperary/Kilkenny group and the West Munster group. Below is a listing of the major cross sites in each group. In addition there is a group of crosses that are identified as twelfth century. These do not necessairly have scripture scenes on them.

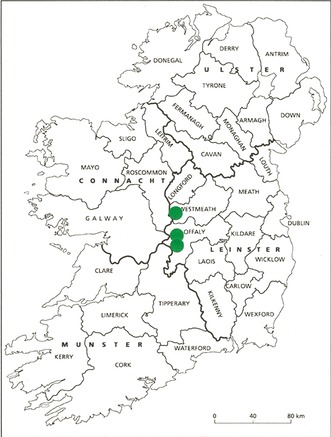

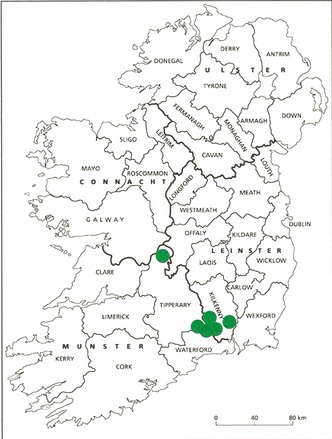

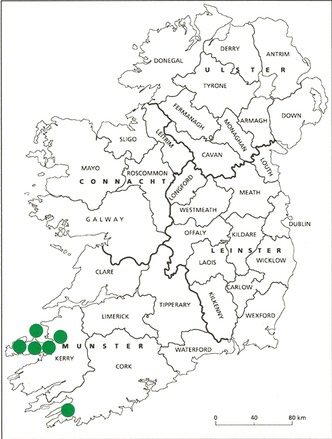

The outline maps below were found at http://www.answers.com/topic/maps-ireland-counties-and-unitary-authorities, January 2014. I have modified each to illustrate the general locations of the crosses in each of these groups.

The Midlands and North Leinster group: Monasterboice (Co. Louth), Kells and Duleek (Co. Meath), Durrow and the Cross of the Scriptures at Clonmacnois (Co. Offaly). (Map below left.)

The Ulster group: Arboe and Donaghmore (Co. Tyrone), Armagh (Co. Armagh), Camus (Co. Derry), Clones (Co. Monaghan), and Galoon (Co. Fermanagh). Outliers include Drumcliff (Co. Sligo) and Carndonagh and Fahan (Co. Donegal). (Map below right.)

The South Leinster group: These are granite crosses. They include Graiguenamanagh North, and Ullard (Co. Kilkenny); Castledermot, Moone and Old Kilcullen (Co. Kildare) and St. Mullins (Co. Carlow). (Map below left.)

The Bealin-Banagher group: the Clonmacnois crosses other than the Cross of the Scriptures and Banagher (Co. Offaly) and Bealin (Co. Westmeath). (Map below right.)

The Tipperary/Kilkenny group: These are sandstone crosses. They include Ahenny and Lorrha (Co. Tipperary) and Kilkieran West, Killamery, Kilree and Tybroughney (Co. Kilkenny). (Map below left.)

The West Munster group: The only datable cross in this group is the cross at Kilnaruane (Co. Cork). Others that are either plain or without chronologically meaningful decoration include: Killiney, The Magharees, Kilmalkedar, Reenconnell and Tonaknock (Co. Kerry). (Map below right.)

The Twelfth Century group: This group is geographically scattered. One obvious large geographical grouping, however, appears in west central Ireland. This group includes: Inishcealtra, Killaloe, Dysert O’Dea, Kilfenora, Killinaboy and Noughaval (Co. Clare); Killeany/Teaglach Einne, St. Macdara’s Island, Temple Brecan, Addrgoole and Tuam (Co. Galway); and Cong (Co. Mayo). Other, more scattered examples include: Graiguenamanagh South (Co. Kilkenny), Cashel, Monaincha, Roscrea and Ballynilard (Co. Tipperary), Downpatrick (Co. Down), Glendalough (Co. Wicklow); Kilgobbin (Co. Dublin); Broughanlea and Tullaghore (Co. Antrim), Tory Island (Co. Donegal) and Kilteel base (Co. Kildare). (Map below)