This page highlights the crosses of County Louth. These include Clonmore cross fragments; the Dromiskin cross, Faughart Cross-base, the Termonfeckin cross and the crosses of Monasterboice. The location of County Louth is indicated by a red star on the map to the right.

Historical Background

County Louth derives its name from the village of Louth or Lu, which seems to have been named for the Celtic god Lugh. “Lugh, whose name means "the shining" is one of the greatest heroes of Irish folklore. He is known under different names but is usually mentioned as Lugh of the Long Arms (sometimes, "Long Hands" or even "Artful Hands”). Lugh - the most powerful of the Celtic gods - is the god of all arts and crafts. Worshiped as the sun god, he symbolizes enlightenment as he brings light to the world.” (Sutherland)

According to Ptolemy’s world map, based on his book Geography, written in about 150, what is now County Louth was in the area of the Voluntii tribe. Their territory was bordered on the south by the Blanii and to the north by the Darini.

By about 300, part of the Voluntii area was known as Breagh. Breagh (Brega, Breaga) was the site of Tara (Temuir), the ancient capital of Ireland. Prior to 500 the area of Breagh was part of Leinster. About 500 the Southern Ui Neill began the process of taking Brega from Leinster. (Charles Edwards p. 156) Tara, associated with the High King of Ireland, was then ruled by the Southern Ui Neill with the High Kingship alternating between the Southern Ui Neill and the Northern Ui Neill of Aileach (County Donegal). Breagh included the southern part of what is now County Louth. The ancient home to the kings of the sub-kingdom of Brega was at Knowth. The northern portion of Louth was part of the Airgialla territory.

The Kingdom of Airgialla was part of the province of Ulster. Beginning in the 6th century, it was a confederation of a number of different and unrelated groups that formed an alliance for mutual defense. At times, because of the nature of the alliance, Airgialla had more than one king. (Airgialla)

The Southern Ui Neill were descendants of Fiacha, son of Niall of the Nine Hostages. Beginning in the 5th century they were expanding into what would become Mide, the “middle kingdom.” At its most extensive Mide included Counties Meath, Westmeath, and parts of Cavan, Louth, northern Dublin, Kildare and Offaly.

During the 8th centuries both Mide and Brega were expanding at the expense of the Kingdom of Ulster. (O Croinin, p. 221)

In the 9th century, present day Louth was divided into three sub-kingdoms. Conaille was associated with the Ulaidh, Fir Rois was associated with the Airgialla and Fir Area Ciannachta was associated with Midhe. (Louth History)

Because both Mide and Brega were ruled by the Southern Ui Neill, by the 9th century the two formed the Kingdom of Mide.

By the 12th century Mide and Brega were contracting in size because of incursions in the north by the kingdoms of Breifne and Fernmag and expansion in the south by Leinster. (O Croinin, p. 925) During this time the O’Carroll Kingdom of Airgialla (Oriel) expanded into the north of what is now County Louth. The O’Carrolls (O’ Cearbhail) Kingdom of Airgialla was divided following the death of King Murchadh in 1189, as a result of the growing strength of the English in Ireland. “The coastal plain between Drogheda and Dundalk, which became known as Louth or Uriel, was rapidly colonized.” (Foster, p. 56)

The map below left suggests that in about 700, Mide and Brega could be distinguished from one another. By about 900, the date associated with the map to the right, Mide and Brega were considered together as the Kingdom of Mide. Between 700 and 900 the two kingdoms expanded in some areas and receded in others.

The source of the map to the left above is https://sites.rootsweb.com/~irlkik/ihm/mide.htm while that to the right was found at

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Meath

Ecclesiastic History

One of the early founders of monasteries in Ireland was St. Finnian of Clonard. He founded the monastery at Clonard, in County Meath about 520. This corresponds to the time when the Southern Ui Neill were expanding into Mide and Brega. St. Ciaran of Clonmacnoise and St. Columcille of Iona studied with Finnian. Clonmacnoise, in County Offaly became a powerful monastery with wide ranging influence. St. Columcille founded numerous monasteries including Derry (County Derry), Durrow (County Offaly), Kells (County Meath) and Swords (County Dublin). These Columban churches were also influential. The great churches such as Armagh, associated with St. Patrick; Clonmacnoise, associated with St. Ciaran; Clonard, associated with St. Finnian; Kildare, associated with St. Brigid and the Columban monasteries, associated with St. Columcille, struggled with each other for influence. Charles Edwards has noted that “The kings of Meath in the eighth century avoided committing themselves to any one great church. Although they favored Durrow, one of Columba’s monasteries, and probably gave the land for the foundation of Kells, another Columban monastery, early in the ninth century, they also promoted Clonard and patronized Clonmacnois.” (Charles Edwards, p. 26)

There were numerous early monasteries in County Louth. As noted below in the List of Monastic Houses in County Louth, (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_monastic_houses_in_County_Louth) several of them were founded by St. Patrick. These early monasteries included:

Ardpatrick Monastery, early site, founded 5th century by St. Patrick

Cluain-brain Monastery, early site, founded 5th century by St. Patrick

Clonkeen Monastery, early site, founded by St. Colman Cule. Also associated with County Laois

Clonmore Monastery, early site

Dromin Monastery, early site, may have been founded by St. Findian

Dromiskin Monastery, early site, founded 5th century by St. Patrick

Drumcar Monastery, early site, founded by St. Fintan

Drumshallon Priory, may have been early, later Augustinian Canons Regular

Dunleer Monastery, early site, founded 6th or 7th century by St. Forodran

Ernaide Monastery, early site, may have been in County Louth

Faughart Monastery, early site, nuns, founded by St. Darerca

Faughart Monastery? may have been early site, monks

Linns Monastery, early site, founded before 700 by Colman (Mocholmoc)

Louth Priory, early site, founded 5th century, possibly by St. Patrick for St. Mochta.

Monasterboice Abbey, early site founded 523 or before by St. Buite

Monasterboice Nunnery, early site founded around 523 by St. Buite

Termonfeckin Abbey, early site, founded 7th century by St. Feching of Fore

Five of these early monasteries are associated with High Crosses. These monasteries are: Clonmore, Dromiskin, Faughart, Monasterboice and Termonfeckin. Background on each of these sites, as available, will be provided in conjunction with the description of the cross or crosses present.

Clonmore Cross Fragments

In an article written in 2007, Michael McKeown reported on what appears to be two fragments of a high cross at the site of the ancient monastery at Clonmore.

Tradition tells us that Clonmore, meaning “big meadow” was founded, probably in the mid 6th century, by St. Columba who placed St. Oissene over it. In 826 it was burnt by the Danes. In 1017 Flaithbeartach Mac Murchertach was abbot. (McKeown p. 336) This last piece of information suggests the monastery was still functioning in the 11th century. The Map of Monastic Ireland, on the other hand, suggests it may not have functioned after the 10th century.

The Cross:

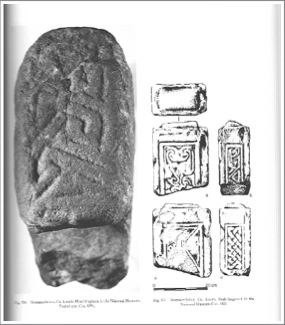

In the ruins of a church there are two sandstone stones that contrast with the limestone of the rest of the building. They are “Built into the masonry in the pier between the first and second windows in the south wall.” (McKeown p. 336)

The upper stone, above left, has “two shallow parallel mortises on its south elevation, and this was recognized as a common device for locating a capstone on the upright shaft of a cross.” (McKeown p. 336)

Lower stone, to the right, has a “portion of a panel surrounded with a moulding enclosing a design of concentric interlacing.” (McKeown p. 338)

Harbison has suggested a 9th century date and noted a parallel with the tall cross at Monasterboice and with the crosses at Duleek and Termonfeckin. (McKeown p. 338)

This suggests a richer history for the Clonmore site than previously evident. (McKeown p. 338)

GettingThere: See the Road Atlas page 28, F 3. Take exit 12 from the M1. Follow R169 northeast to the R132 into Dunleer. Just north of Dunleer take the Mountain View Road toward Clonmore and Togher. The church graveyard is on the north side of the road.

Dromiskin Cross

The cross described here is located at the site of the Dromiskin Monastery in County Louth. It may, however, have been moved there from “the old monastery of Baltray” nearby. (Lawless, p. 301) Contrary to Lawless, I find no mention of a monastery at Baltray at any time. The Baltray community and that of Termonfeckin (described below) are quite close and there was certainly a monastery at Termonfeckin.

The date of the founding of the monastery is a matter of some question. Writing in 1897, F. W. Stubbs reported that a church or monastery was established at Dromiskin in the 6th century. He reported the tradition that it was established by Saint Patrick. The first bishop or abbot of the monastery was Lugaidh, son of a king of Munster. He died in 515 or 516 CE, suggesting that the monastery was established in the very early 6th century. (Stubbs, p. 102)

Writing in 1904, Laurence Murray and Locan P. Ua Muireadhaigh suggested that Stubbs and others confused the monastery at Dromiskin (Drominiscleann) with that at a place nearby called Drumshallon. They state that it was Drumshallon that was founded in the 6th century by St. Patrick, while Dromiskin (Drominiscleann) was founded in the 7th century by Saint Ronan. (Murray, p. 31)

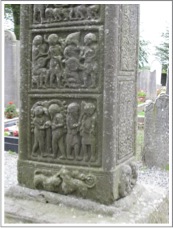

The photos left and right were taken in 2015. On the right is the East Face and on the left the West Face.

The photos left and right were taken in 2015. On the right is the East Face and on the left the West Face.

As noted above, the history of Dromiskin is a little confusing. There are a few mentions of the monastery in the historic record. Whether he or St. Patrick founded the monastery, Saint Ronan was a famous bishop of Dromiskin. He died during a “pestilence” known as the yellow jaundice in 664. (Murray, p. 31) The first mention of Dromiskin (Druim-Ineasglainn) in the Annals of the Four Masters is for the year 788. It tells of “Crunnmhael of Druim Inesglainn, Abbot of Cluain Iraird Clonard.” (Annals of the Four Masters, 788) Abbots of Dromiskin mentioned in the Annals include Muirchiu (died 826); Tighernach son of Muireadhach (died 876); Cormac, son of Fionamhail (died 887); Muireadhach, son of Cormac (died 908) and Maenach, son of Muieadhach (died 978). (Stubbs p. 102-105)

The duration of the monastery is also an open question. In addition to a partial head of a High Cross, there is also a Round Tower at Dromiskin. William Stubbs dated the round tower to the 9th century and suggested that by the end of the 10th century the monastery lay in ruins. This supposition is challenged by more recent researchers. Brian Lalor, a scholar of the round towers of Ireland, estimates the tower to date from the 12th century. (Lalor, p. 185) The Map of Monastic Ireland, published by the Ordnance Survey Office states that the monastery probably continued till after 1111. (Map of Monastic Ireland) This is the date of an ecclesiastical assembly held at Raith Bressail that legislated for an island wide diocesan hierarchy. (O’Croinin, p. 915) According to the information sign at the site, “the monastery of Dromiskin was plundered by the Irish in 908, by the Danes in 978 and again by the Irish in 1043.” All of this suggests that the monastery endured at least into the 12th century.

The Cross Head

The cross head stands on a modern base and shaft. It was erected in its present location in 1916. Prior to that the head had served as a headstone for the Lawless family. It is a ringed cross that is imperforate. On both faces there is ring moulding along the outer edge of the cross and delineating the panels where figural scenes and geometric patterns are carved. (Harbison, 1992, p. 69) Because the cross has definitely been moved, it is unclear how it was determined which face is which.

The East Face

Center: In the center of the head is a square panel that is raised from the face of the cross. On it are four dragon or serpent-like figures that appear in profile. Their jaws are open and Roe suggests they have “long tongues lolling from fanged jaws.” (Roe, p. 113) Harbison disagrees stating “the heads of these animals are seen in profile and they devour the heads of smaller animals whose heads are seen from above.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 69) Both agree their tails reduce in size and curl counter clockwise into a boss-like knot in the center of the panel.

There are other crosses that have a type of whorl pattern in the center of the west face. For more information on this see “Whorls and Spirals on the Irish High Crosses” (https://www.academia.edu/36478048/Whorls_and_Spirals_on_the_Irish_High_Crosses

The whorl on the Dromiskin cross contains dragon or serpent-like heads that emerge at the corners of the central panel on the cross. There are at least three crosses, Dromiskin, Kilamery and Moone that have dragon or serpent-like figures on the head of the cross, either on the west or east face. What does this unusual iconography mean? Does it have a religious message? As Robert Bagley suggests, the question could be changed as follows: What thoughts would this cross, this image evoke in the mind of a religious or a lay person of the time of its carving? The answer to this latter question, he points out, “will always be historical."(Bagley, p. 8)

Taking the historical context seriously, there are some clues to meaning in a book by James H. Clarlesworth, The Good and Evil Serpent: How a Universal Symbol Became Christianized. In the Middle East the serpent symbolism carried a variety of contradictory meanings: “light and darkness, life and death, good and evil, Satan and God.” (Charlesworth, p. 417) As late as the 4th century Christian writers like John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople, were able to parallel Jesus and the serpent. His analysis was based on a story from the book of Numbers (Numbers 21:4-9) During the time in the wilderness the people spoke against God and Moses. God sent serpents, they bit people, and many of the people died. The people prayed for relief and God told Moses “ Make a fiery serpent and set it on a pole, and everyone who is bitten, when he sees it, shall live.” (Numbers 21:8) Moses did so, he made a serpent of bronze and put it on a pole in the center of the camp. The cure was effective. As Chrysostom noted, that story was referred to in the Gospel of John. “And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life.” (John 3:14-15) In his thirty-seventh homily on the Fourth Gospel, Chrysostom wrote: “In the former, the uplifted serpent healed the bites of serpents; in the later, the crucified Jesus healed the wounds inflicted by the spiritual dragon. In the former, he who looked with these eyes of earth was healed; in the latter, he who gazes with the eyes of his mind lays aside all his sins.” (Charlesworth, p. 415)

This interpretative history of the symbol of the serpent might suggest that the serpents represent Christ, or at the least, the resurrection and eternal life of the believer. But there is a fly in the ointment. Charlesworth informs us that during the 4th century, the very time Chrysostom was writing, a shift was already taking place in the Christian interpretation of the serpent symbol. It was becoming less dominantly positive and increasingly negative. (Charlesworth, p. 417) This change in focus was largely based on passages in the book of Revelation. “And the great dragon was cast down, the old serpent he that is called the Devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world.” (Revelation 12:9) The serpent came increasingly to represent Satan.

Given that the Dromiskin cross probably dates from around the 9th century, it is unlikely that the serpent symbolism has a positive connotation. This leaves us guessing again what the meaning might be. If the serpent represents Satan or evil, could its presence on the head of the cross be a declaration of the victory of Christ on the cross over sin and death?

Figural Art: There is figural art in each of the panels surrounding the center of the cross. Above the raised panel there appears to be an animal. The damage to the upper arm of the cross prevents a more exact description. Below the panel is the upper part of the figure of an angel. The head, upper body and wings are clearly visible.

The left arm of the cross (as you face it) contains a hunting scene. A rider on horseback follows his dog. The dog is chasing a stag toward the center of the cross. Helen Roe offers the following appraisal of the scene: “Hunting scenes are not uncommon in Christian art. They are derived from Pagan decorative motifs and from an early date appear in conjunction with subjects illustrating Christian narrative. By the early medieval period various symbolic or allegorical meanings for such compositions had been formulated, as, for example, that which identifies the Stag with the sinful soul, pursued by hounds which represent virtues such as Truth, Charity or Humility and hunted by a rider — a bishop or saint — into the safety of the Church.” (Roe, p. 113)

There is a similar scene on the cross at Kilamery. It is difficult to make out and not pictured here. Harbison describes it as follows: “a horseman hunting a stag with a dog already on its back.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 123) This gives the crosses at Dromiskin and Kilamery two similar panels on the west head.

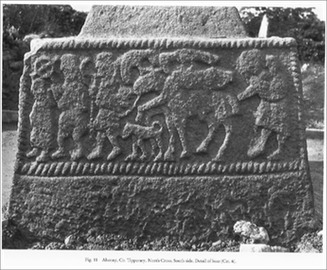

The scene on the right arm of the cross depicts a horse with what appears to be a headless body on its back. It is moving away from the center of the cross. Ahead of the horse is a man who carries what seems to be the head of the corpse on his back. This procession moves toward a figure on the far right who, with outstretched arms, appears to welcome the bearer of the head. This scene is a simplified version of a scene on the south side of the base of the North Cross at Ahenny, Co. Tipperary. (Harbison, 1992, p. 69; Image below from Harbison, 1992, volume 2, plate 11)

The interpretation of both scenes is problematic. Harbison suggests it may represent David bringing the head of Goliath to King Saul. The problem with this interpretation lies in the fact that I Samuel 17:54 only mentions David bringing the head of Goliath to Saul, not the body. (Harbison, 1992, p. 12)

The interpretation of both scenes is problematic. Harbison suggests it may represent David bringing the head of Goliath to King Saul. The problem with this interpretation lies in the fact that I Samuel 17:54 only mentions David bringing the head of Goliath to Saul, not the body. (Harbison, 1992, p. 12)

Other suggested interpretations of the scene also fail to convince. Helen Roe wrote: “For this latter cross [Ahenny] it has been suggested that the subject depicts the funeral of Cormac mac Cuillenan, bishop-king of Cashel, after the battle of Ballaghmoon in 908. This interpretation, all things considered, is not really satisfactory for either Ahenny or Dromiskin.” (Roe, 113)

Francoise Henry thought the scene might “represent the bringing of relics and possibly, in the case of Ahenny and Dromiskin, of those of a beheaded saint, represented realistically in terms of contemporary warfare.” (Henry, p. 53)

To the right of the whorl on the cross at Kilamery there is also a procession scene. “A chariot procession, having a man with a crook or crozier on or above the horse, and a number of human figures in front. There would seem to be animals beneath the chariot.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 123) This offers another, partial, similarity between the crosses at Dromiskin and Kilamery in that they both have procession scenes. Of course the scenes are also different in significant ways. If a particular meaning or reference was intended, it is open to interpretation.

The West Face

Peter Harbison offers a simple description of the art work on the west face of the cross. “There is a round domed boss with a whorl in the centre, from which spirals with trumpet patterns emerge. In the sunken panels on the arms and shaft surrounding it there are raised bands of interlace forming pointed triangles.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 69) Helen Roe offers a more technical description. “The center of the head is filled by a large round boss which seems to be decorated by a triskele spiral design with lentoid bosses.” (Roe, p. 114) This is all somewhat difficult to make out in the image to the left.

Peter Harbison offers a simple description of the art work on the west face of the cross. “There is a round domed boss with a whorl in the centre, from which spirals with trumpet patterns emerge. In the sunken panels on the arms and shaft surrounding it there are raised bands of interlace forming pointed triangles.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 69) Helen Roe offers a more technical description. “The center of the head is filled by a large round boss which seems to be decorated by a triskele spiral design with lentoid bosses.” (Roe, p. 114) This is all somewhat difficult to make out in the image to the left.

The triskele is the very common triple spiral. It is found in both pre-Christian and Christian art in Ireland. In Christian art it came to represent the Trinity and eternal life. The image on the right below is a simple version of the triskele. (Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triple_spiral 11/2013) The image in the center below is another, more complex example of the triskele. Note that, in this case, each of the three spirals terminates with what looks like a crescent moon facing the outer rim of the design. This is the trumpet or lentoid pattern. (Source: http://www.timetrips.co.uk/rom-art-style.htm)

Roe goes on to describe the image surrounding the central boss. “Surrounding this boss and drawn out to the full extent of each arm and of those parts of the shaft which remain, are two slender cords forming a cruciform design. These are intertwined in Triquetra form at their four points of contact with the centre boss and looped into a double knot at each extremity of the arms.” (Roe, p. 114)

The image on the right above is a simple example of the triquetra design. (Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trefoil_knot#Trefoils_in_religion_and_culture) Like the triskele, the triquetra often symbolizes the trinity in Christian Art.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 28 2 E. Take the M1 to exit 15. Go right into Castlebellingham, then north into Dromiskin. The location of the cross is indicated by the white circle on the map.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer

Faughart Upper Cross

The Site

Faughart is both the traditional birthplace of Saint Brigid, and the burial place of Edward Bruce, the last high king of Ireland. Faughart fhas also been linked to the Tain Bo Cualinge. The graveyard contains a number of archaeological monuments including the nave and chancel of a church, the graveyard enclosure, a high cross-base and the possible base of a round tower. Saint Brigid was one of the three patron saints of Ireland along with Colum Cille and Patrick. She is typically associated with Kildare.

The Cross-Base, St. Brigid’s Pillar: This large flat topped granite block with a tenon, stands in the center of a ring of what appears to have been the base of a round tower. This suggests the base was moved at some point in time to its present location. The rough cross that stands in the base presently is a later cross.

A fragment that may have belonged to the original cross was found in the graveyard wall and is now in the Dundalk Museum. The fragment (dims. l.34m by 0.31m) is from the center of a small cross. On one side is a boss and the other has a ring with a central cup-mark. The photo to the left is from Faughart, Co. Louth — the hill of heroes, saints, battles and boundaries. The photo to the right was found in Faughart Graveyard Conservation and Management Report.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 19, 5 B. From the N1 take exit 18 and go north less than 2 km toward Faughart Upper. See the map to the left.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Termonfeckin Cross

Tradition holds that a monastery was founded at Termonfeckin in about 665 by St. Fechin. Fechin is more famously remembered as the founder of the monastery at Fore in Co. Galway. Little seems to be known about the history of this monastery. What is known is that:

- the High Cross was erected in the 9th or 10th century at a time when the monastery was apparently thriving;

- the Vikings plundered the foundation in 1013;

- the clan Ui-Crichan of Farney looted the monastery on Christmas Day 1025;

- Raiders from Bregia (Meath) attacked the monastery in 1149;

- in about 1144-1148 the Augustinians established a monastery at Termonfeckin and later a nunnery;

- the nunnery, but not the monastery survived till the suppression of monasteries in 1539;

- the graveyard around St. Fechin’s Church of Ireland, where the High Cross is located, was part of the monastic foundation.

The Cross

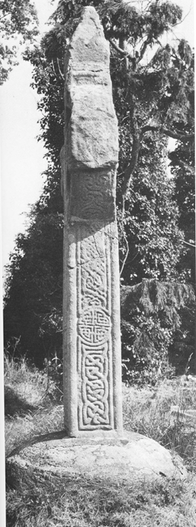

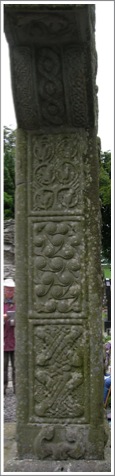

The cross is made of sandstone and is ringed. It has a gable roof and stands on a round base.

The descriptions below are based on or quoted from Harbison, 1992, pp. 170-171.

East Face: (photo below)

E 1: A panel of “irregularly interlinked C-shaped spirals of pelta type which expand into animal heads top and bottom.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 170)

E 2: Two human busts surrounded by arabesque scrolls.

Head: A crucifixion scene with Stephaton Longinus and an angel with wings spread above Jesus’ head. (photo right)

Arms: There is a figure on each arm that might represent Saints Paul and Anthony, based on the right-hand figure holding what appears to be a crook. They might also represent Sun and Moon holding torches. Continuing a tradition from the pre-Christian past, the Sun and Moon appeared in various Christian iconography in images such as the Baptism, the Good Shepherd and Christ in Majesty. Augustine believed the sun and moon symbolized the prefigurative relationship of the two Testaments: the Old (the moon) was only to be understood by the light shed upon it by the New (the sun). This imagery carried over into some depictions of the Crucifixion.

South Side: (photo to the right) (Harbison, Vol. II, Fig. 585)

S 1: A panel of interlace.

S 2: A circle of interlace with four quadrants.

S 3: Animal interlace.

There is a pelta-shaped design on the underside of the ring. The decoration on the end of the arm is not clear.

West Face: (photos left and below right) (Harbison, Vol. II, Fig. 588)

W 1: Interlace

W 2: Fretwork that has an X-shaped design below and a looser fretwork above.

Head: The Last Judgment. Christ stands holding a “blossoming scepter in his right hand and a cross-staff in his left.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 170) There are two heads on each side that may represent women. A spiral design adorns the ends of the arms. Above Christ is a figure that is likely an angel. Above this there is a panel of interlace.

Ring: The ring contains interlace on the two right-hand arcs, C-shaped spirals on the lower left. The upper left segment is damaged.

North Side: (photo to the right) (Harbison, Vol. II, Fig. 588)

Shaft: There is a rounded interlace in the center of the shaft. Below this is spiral fretwork; above it are intertwined beasts with heads facing one another.

Ring: “C-shaped pelta-type designs interlocking horizontally and vertically.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 170)

End of Arm: Spiral fretwork.

Upper side of ring: “Two upright groups of interlace running side by side.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 170)

North side pictured left and right.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 28 3 F. From Drogheda take the R166 northeast to Termonfeckin. The cross is located on the grounds of the protestant Church. The site of the cross is marked by the white circle on the map.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer

Monasterboice Crosses

The Site

Monasterboice was founded by Buithe mac Bronach, who died in 521. Like some other early Irish monasteries, it seems to have been a “double” monastery, with both men and women.

Through the period of Viking raids, Monasterboice was never sacked. It may be that settlement in this area by the Norse was largely peaceful.

In the descriptions of the crosses of Monasterboice I rely on the works of Peter Harbison and Helen Roe. The photo to the right below shows the Tall Cross and the Round Tower.

Helen Roe outlines the history that is known through the Annals. (Roe, 2003, pp. 8-11).

- 762, an abbot of Monasterboice is drowned in the River Boyne.

- 825, Eoghan Mainistrech, a candidate for the abbacy of Armagh is driven out of Armagh by a rival.

- 827, Following the battle of Leth Cam, Eoghan becomes abbot of Armagh with the support of Nial mac Aedha, who later became High King of Ireland.

- 853, another abbot of Monasterboice is drowned in the River Boyne.

- 922, Muiredach mac Domhnaill, abbot of Monasterboice becomes abbot-elect of Armagh. He was also a steward for a large part of the parochia of Armagh.

- 964, Dubhdhabhoireann, abbot and bishop of Monasterboice is described as the “sage of learning of all Leinster.”

- 968, Monasterboice is sacked by the High King of Ireland.

- 1056, death of Flann, son of Flann, “lector and professor of history . . . outstanding master of Ireland in wisdom, literature, history, poetry and science.”

- 1092, abbot Cormac is described as “head of the Irish in learning.”

- 1097, Round Tower at Monasterboice burned along with books and other valuables.

- 1104, Feidhlidh, abbot of Monasterboice, “a learned historian” and the son of Flann died.

- 1117, Eoghan, a grandson of Flann and abbot of Monasterboice died.

- 1122, Fergna, grandson of Flann and abbot of Monasterboice died. He was the last recorded abbot of Monasterboice.

During much of its history, Monasterboice seems to have been a large and prosperous monastery, a center of learning with a well stocked library and numerous scholars. Following the burning of the Round Tower in 1097, the community began a sharp decline. The site was not later adopted by the Augustinians, as was true of the monastery at Termonfeckin and others. It continued as a parish. It was, and is a site of pilgrimage.

The present site contains what would have been the center of the monastery, the most holy part of the foundation. Aerial photography reveals that there were two more boundaries around the center. These three concentric enclosures covered about 59 acres. The center, where the church, the round tower and the high crosses are located may have been based on the biblical city of refuge, a place of sanctuary. (Murphy, pp. 15 and 17)

The Saint:

Monasterboice was founded by Buithe mac Bronach, also known as Boethius or Buite. He was born in Scotland, went on pilgrimage to Rome and studied in Italy. He died in 521.

Muiredach’s Cross

This sandstone cross has had a variety of names. It is the South Cross and was formerly known as St. Patrick’s or St. Boyn’s Cross. The name Muiredach has been attached to it because of an inscription that reads, “a prayer for Muiredach for whom the cross was made.” This Muiredach is generally taken to be an abbot who died in 922/3. This would date the cross to the early 10th century. It has also been suggested that it may refer to an earlier Muiredach who died in 844, which would date the cross to the early to mid 9th century. (Roe, 2003, pp. 27, 29 and Harbison, 1992, p. 140)

This cross is a prime example of the Scripture Crosses. Roe, reviewing the subject matter of the panels tells us that what we see is “the whole dogma of faith — sin, the means of salvation, judgement, heaven and hell.” (Roe, 2003, p. 27)

The base of the cross is 30” (77cm) tall and measures 5’3” (1.6m) x 4’9” (1.45m) at the ground. The cross is 14’6” (4.43m) tall and measures 7’ (2.14m) across the arms. The shaft measures 31” (79cm) x 20” (51cm) where it connects to the base.

East Face:

Base: There is an upper and lower register, the lower being divided in two. The left side of the lower register is worn, but Harbison suggests it may have contained a chariot scene. The right side has interlace.

The upper register has been identified by Roe and others as having signs of the zodiac. These are, right to left, “Gemini, the twins; Capricornus, the goat; Taurus, the bull and Leo, the lion. Harbison declines to identify this scene. He describes two figures kneeling on the right, then a lion or centaur facing away from the two figures. Moving toward the left, he sees two lions, possibly fighting. The base is pictured above left. (Roe, 2003, p. 38; Harbison, 1992, p. 140)

Shaft: On the plinth there are two cats or lions.

E 1: There are two scenes. On the left we have Eve giving the apple to Adam. On the right we have Cain slaying Abel. These stories are told in Genesis, chapters 3 and 4.

E 2: David and Goliath: This panel is actually two scenes running left to right like a cartoon strip. The left side shows Saul, who sent David out to fight Goliath. Right of him, David stands facing Goliath with his sling, his bag of stones and his curved staff. Next, we have Goliath, who has already been struck by David’s stone and is falling to his knees. On the far right is Goliath’s armor bearer who looks on in awe. This story is told in 1 Samuel chapter 17. The plinth, E1 and E2, are shown in the photo to the right.

E 3: Moses Strikes the rock and God provides water. Moses on the left strikes a rock directly in front of him. The children of Israel sit in two rows, each holding a drinking horn. This story is told in Exodus 17:1-8.

E 4: The Adoration of the Magi. This scene has raised questions because there are four figures approaching Mary and the Christ child. Roe sees the first figure, who is dressed differently from the others as St. Joseph. He is leading the magi to Mary and the child. Harbison sees this as an example where there are four magi rather than three. This follows Psalm 72:10 that names four places the kings come from, and reflects details in two other carvings, one in Yugoslavia the other in England. Other explanations for the first of the figures to approach Mary and the child have also been offered. This story is told in Matthew 2:1-11. E 3 and E 4 are shown in the photo to the left. (Roe, 2003, p. 40; Harbison, 1992, pp. 243-245 and 141)

Head and Arms: The Last Judgment. In the center Christ stands holding a cross, symbol of his resurrection, and a flowering rod, symbol of his role as judge. Above his head is a large bird. It may represent the phoenix, symbol of resurrection. On the left, as we view it, an angel holds a book. Behind him a harper, possibly David, plays. Next in line is a piper, then another figure holding a book, perhaps for singing. The left arm is filled with images of the good. On the right of Christ is a seated musician. Then a devil with trident herds the bad toward eternal damnation. Below Christ’s feet St. Michael weighs a soul, defending it against a devil that attempts to upset the balance.

Head and Arms: The Last Judgment. In the center Christ stands holding a cross, symbol of his resurrection, and a flowering rod, symbol of his role as judge. Above his head is a large bird. It may represent the phoenix, symbol of resurrection. On the left, as we view it, an angel holds a book. Behind him a harper, possibly David, plays. Next in line is a piper, then another figure holding a book, perhaps for singing. The left arm is filled with images of the good. On the right of Christ is a seated musician. Then a devil with trident herds the bad toward eternal damnation. Below Christ’s feet St. Michael weighs a soul, defending it against a devil that attempts to upset the balance.

Above the Last Judgment is a scene that has been variously interpreted as Saints Paul and Anthony overcoming the devil; Saints Paul and Anthony breaking bread in the desert; and Columcille contesting with a druid. Roe suggests it may be the enthroned Christ flanked by angels. (Harbison, 1992, pp. 141-2; Roe, 2003, p. 42) See the photo to the left.

South Side

Base: The lower register is damaged but may have contained figure sculpture. The upper register seems to depict a chariot procession. (Not shown.)

Plinth: Two quadrupeds back to back, each eating its own tail.

S 1: Human interlace. Eight humans form two X-shaped interlaces.

S 2: Interlinked bosses with “one serpent devouring another in each corner.”

S 3: Inhabited vine-scroll, branches with grapes. Six lambs are present, one in each circle formed by the branches and two birds peck at the branches at the top.

See the photo to the right.

Head: See the photo to the left. The underside of the ring has a central panel with two serpents in figure 8s with three human heads intertwined. A panel of interlace is on each side of the central panel.

Head: See the photo to the left. The underside of the ring has a central panel with two serpents in figure 8s with three human heads intertwined. A panel of interlace is on each side of the central panel.

Underside of Arm: Two interlocked animals.

End of Arm: Pilate washes his hands.

Top of Ring: A panel of meander flanked on each side by panels of interlace.

Top: This panel has been given many interpretations: a Horseman of the Apocalypse, the Entry of Christ into Jerusalem, and the escape of Columcille with the Psalter. There is an angel in each upper corner.

West Face:

Base: The lower register has a panel of fretwork on the left and a panel of interlace on the right. The upper register contains a hunting scene, though some have identified it as a series of Zodiac signs. (See the photo to the left.)

Plinth: Two cats, one holding a kitten, the other about to eat a bird. In the background is an inscription that has been interpreted as:

“Prayer for Muiredach who had the cross erected.”

W 1: The Second Mocking of Christ. Christ in a purple or scarlet robe and holding a reed is flanked by two soldiers holding swords.

W 2: The Raised Christ, students or ecclesiastics, the incredulity of Thomas, or a Council of Saints judging Columcille. Three figures each seem to hold a book. The center figure raises his right hand in a sign of blessing.

W 3: Traditio Clavium. Christ in the center hands a key to St. Peter on the left and a book to St. Paul on the right.

Head: The lower panel contains a boss at each corner. Serpents unroll from the bosses and there is interlace at the center.

Center: The Crucifixion with Stephaton holding vinegar and Longinus piercing Christ’s side. Beside Christ’s thighs on each side is a head that may represent Sol and Luna. Under each of Christ’s hands is a figure that could represent Tellus (the element of water) and Gaia (the personification of Earth).

North Arm: The Denial of Peter contains six figures. By analogy to the Durrow cross, Harbison identifies the scene as “St. Peter among the soldiers in the court of the High Priest denying Christ thrice.”

South Arm: The Resurrection is indicated by the inverted U in the center of the panel that represents the tomb. A soldier kneels on each side. Above it, Christ rises. There is a cross formed by the space between and above the legs of the soldiers. Christ’s arms are supported by an angel on each side.

Upper Panel: Animal interlace with a human head at the top.

Top: The Ascension is indicated by the image of Christ in the center with an angel with wings on each side. The angels hold up Christ’s hands.

Ring: There are panels of “running animal scrolls.”

(Harbison, 1992, pp. 143-145)

South Side:

Base: The lower register has a panel of fretwork on the left and of interlace on the right. The upper register contains what Harbison identifies as a Hunting Scene with a horseman, two centaurs, one firing an arrow at a quadruped running to the left.

Base: The lower register has a panel of fretwork on the left and of interlace on the right. The upper register contains what Harbison identifies as a Hunting Scene with a horseman, two centaurs, one firing an arrow at a quadruped running to the left.

Plinth: There are two seated men with legs intertwined. They are pulling each others’ beards.

See photo to the left.

N 1, 2, 3: Panels of interlace that form six circular motifs. See photo to the right.

Head: See the photo to the right.

Under the ring is a central panel of two snakes similar to that on the south side. The flanking panels have fretwork.

Under the arm is the Hand of God, specifically the left hand.

End of the Arm: The Mocking or Flagellation of Christ. A seated Christ is struck on the shoulders by soldiers. There are three angels above.

Top: Anthony and Paul breaking bread in the desert. The saints face one another. Their crooks cross. Above this a loaf of bread is brought by a Raven. There is a handled chalice between the feet of the saints. In the gable of the roof is a boss with animals emerging from it.

Monasterboice Tall Cross

The base of the cross is 25” (65cm) tall and measures 4’6” square at the ground. The cross is 21’ (6.45m) tall and measures 7’ (2.13m) across the arms. The shaft is 25” (64cm) x 16” (40cm). The Tall or West Cross is the tallest of the surviving High Crosses in Ireland. The base is undecorated. The components of the cross (shaft and head) are separate pieces.

East Face: See the photo to the right.

Plinth: No decoration remaining.

E 1: David Slays the Lion. David pulls apart the jaws of the lion. Behind him, to the right is his staff, a sling-stone and two sheep.

E 2: Sacrifice of Isaac. Abraham on the left hold Isaac’s head on the altar. Above right an angel holds the leg of the ram.

E 3: This panel has been interpreted in several ways, two of which are: Moses Smites Water from the Rock; and Worship of the Golden Calf. There is a tall figure (Moses) with a staff on the left of the panel. On the right are two rows of two figures each with shields and an additional figure kneeling at the bottom of the panel. The interpretation hinges on the identification of the image in the top center of the panel. Is it a rock in the wilderness with streams of water flowing down, or is it an image of the Golden Calf? (Harbison, 1992, p. 147; Roe, 2003, p. 53)

E 4: This panel has two images. On the left David holds the Head of Goliath. On the right Samuel anoints David.

E 5: This panel also has two possible interpretations. Harbison interprets it as Sampson Rending the Pillars of the House. Samson on the left, his long hair flowing down his back is beginning to push over a house pillar. Eight Philistines are seated on the right. Roe and others interpret it as Goliath challenging the army of Israel. This would link the scene with that below it. (Harbison, 1992, p. 147; Roe, 2003, p. 55)

E 6: Elijah Ascends to Heaven: A winged horse pulls a chariot. There appear to be three figures in the chariot. One would be identified as Elijah. The story is told in 2 Kings 2:9-12.

E 7: Interlace

Head: The head has a panel above and below the center, an image on each arm, decoration in the narrowings and a central figural image.

Lower Panel: The Three Children in the Fiery Furnace. Soldiers flank an angel who is protecting the children with its wings.

South Arm: The Temptation of St. Anthony. Two devils flank St. Anthony.

North Arm: Saints Paul and Anthony overcome the devil in human form. The devil (upside down) is faced by the saints, each of whom holds a staff.

Upper Panel: Christ Walks Upon the Water. Two figures appear to be outside a boat. One (St. Peter) is kneeling, the other (Jesus) standing. Jesus reaches out to deliver Peter from drowning.

Center: Once again there are numerous interpretations. Two are mentioned here. Harbison sees this as David Acclaimed King of Israel. The central figure, and those on each side hold shields. The central figure also has a sword and a staff. An angelic figure is to the right of the head of the central figure. Roe sees this as The Second Coming of Christ to Judgment. Describing the scene in the same way as Harbison, she comes to a different conclusion regarding the interpretation.

Top: Harbison suggests this may represent the Repentance of Manasseh. The story is told in 2 Chronicles 33 and 2 Kings 21. Here it is possible we see Manasseh on the right about to destroy an idol or to offer a sacrifice. The ring above the back of the animal, Harbison interprets as one of the groves which Manasseh set up.

South Side: See photo to the right

Plinth: a panel of interlace.

S 1: A defaced panel that may have figure sculpture.

S 2: Five bosses with serpents uncoiling.

S 3: This image may represent Zacharias, Elizabeth and the infant John the Baptist. The figures above each head have been identified as lizard-like animals or distorted angels. (Harbison, 1992, p. 149; Roe, 2003, p. 58)

S 4: Animal interlace forming two X-shapes.

S 5: The Naming of John the Baptist. Zacharias writing the name John on a tablet. Two quadrupeds are above, which would fit with the scene taking place in the Temple.

S 6-7: Worn panels, the lower containing bosses.

Head: See the photo to the left. The lowest panel (not shown) contains a winged animal. The under side of the ring has raised panels of interlace flanking a sunken area with a lozenge-shaped panel of interlace. The underside of the arm is not decorated. The end of the arm has fretwork in the center. The upper panel has interlace.

Top: Interlinked bosses are below the gable of the house-shaped roof.

West Face: See the photo to the right.

Plinth: The decoration is too worn to identify.

W 1: Christ in the Tomb. Christ lies beneath a stone with soldiers seated above, each holding a spear. A cross rises in the center of the image. The left corner is damaged. The scene seems to follow the same pattern as appears on the Cross of the Scriptures at Clonmacnois.

W 2: The Baptism of Christ. John the Baptist on the left appears to read from a book while the figure of Jesus is in front of him and two other figures are on the right behind him.

W 3: The Three Holy Women at the Tomb. Three figures stand frontally, each appearing to carry something. This scene has also been interpreted as The Transfiguration and the Journey to Emmaus. Panels W 3-6 taken together have also been interpreted as the twelve apostles.

W 4: Traditio Clavium. Christ in the center hands a key to St. Peter on the left and a book to St. Paul on the right. The scene has also been interpreted as the Arrest of Christ, the Journey to Emmaus and the Transfiguration.

W 5: Three figures are shown frontally. The scene has also been interpreted as Ecce Homo, Christ led to Annas the High Priest, Moses, Aaron and Hur and the Incredulity of Thomas.

W 6: Soldiers Casting Lots for Christ’s Garments. The central figures holds a sword or knife. Comparing this to a scene on the Cross of the Scriptures at Clonmacnois, this identification makes sense. It has also been interpreted as Ecco Homo and The Arrest of Christ.

W 7: This may have contained figure sculpture but is badly worn.

Head: The decorations on the head are all related to the crucifixion. See the photo to the left.

The lower panel shows two soldiers holding up sticks that seem to support a curved platform below Jesus’ feet. A bird is on the ground between their feet.

The center shows the crucifixion with Jesus flanked by Stephaton and Longinus The bosses behind these two figures probably represent Sol and Luna.

The two contractions represent the Denial of Peter. On the right Peter warms his hands over the brazier while a cock crows above his hand. On the left, a servant girl stretches an inquiring hand toward Peter on the right. Another cock is with her. This scene has also been interpreted as a man milking a sheep and one shearing or sacrificing a sheep. Both are symbols of the Atonement. (Harbison, 1992, p. 151; Roe 2003, p. 52)

The left arm illustrates the Mocking of Christ.

The right arm illustrates the Kiss of Judas.

The upper panel illustrates Peter drawing his sword to cut off the ear of Malchus.

Top: Pilate Washes his Hands.

North Side:

Because it stands so close to a ruined church, the north side of the cross is difficult to photograph. The two photos below show the shaft of the cross on the north.

Plinth: Worn beyond recognition.

Plinth: Worn beyond recognition.

N 1: C-shaped spirals curling into spirals on the top and bottom, and probably having serpents emerging from the bosses. (Harbison, 1992, p. 151)

N 2: David as King. David is in the center seated. On his left shoulder is a bird. Beside his legs on each side is a hound.

N 3: Fretwork with spiral bosses.

N 4: Daniel in the Lions’ Den. Daniel in the center fends off a lion on each side.

N 5: Interlace

Head: (Not shown)

Lower Panel: A winged Griffin.

Underside of Ring: The under side of the ring has raised panels of interlace flanking a sunken panel with interlace.

End of Arm: Fretwork

Upper side of Ring: Raised panels flank a sunken panel. All are undecorated.

Upper Panel: Two strands of interlace.

Top: Eight interlinked bosses.

North Cross:

This is a composite cross. We have the bottom of a shaft and a head, joined by a modern section of shaft. They probably represent two original crosses. The photo to the left shows the west face while the one to the right shows the east face.

The Lower Shaft:

While this fragment probably had figure sculpture, only a few remnants remain, and they cannot be interpreted.

Cross Head and Upper Shaft:

The shaft is undecorated.

East Face: A raised boss in the center bearing C-shaped spirals. There may have been interlace on the top. See the photo below left.

West Face: The Crucifixion with Stephaton offering wine and Longinus piercing Christ’s side. The arms and top may have contained decoration. See the photo below right.

Cross Shaft:

This shaft was assembled from a number of fragments. It has no discernible ornament or sculpture. A mortise at the top has been broken out on one side.

In the photos left and right both faces of the shaft are shown.

Head Fragment:

The fragment has a height of 24" (61cm). On one face is a Crucifixion scene and a possible panel of interlace on the arm. On the other face is a boss from which serpents emerge. The end of the arm has a panel of fretwork. See the photo to the left.

Shaft Fragment:

This fragment stands 11” (28 cm) high The design on one face is not clear. On the other is a pattern of interlocking C-shaped scrolls. One side has interlace, the other fretwork. See the photo to the right.

Both the head fragment and the shaft fragment are in the collection at the National Museum in Dublin. The photos above and to the right are borrowed from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Figs. 504-507.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 28, 3 E. The site can be reached and is signposted from exit 11 of the M1.

Map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Resources Cited

Airgialla: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kings_of_Airg%C3%ADalla

Annals of the Four Masters, source http://www.ucc.ie/celt/publishd.html

Bagley, Robert W., “Meaning and Explanation,” Archives of Asian Art, Vol. 46 (1993), University of Hawaii Press, pp. 6-26.

Bolton, Jason, Faughart Graveyard Conservation and Management Report. For Louth County Council

Charles-Edwards, T.M., Early Christian Ireland, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Charlesworth, James H., The Good and Evil Serpent: How a Universal Symbol Became Christianized; The Anchor Yale Bible Reference Library, Yale University Press, 2010

Faughart, Co. Louth — the hill of heroes, saints, battles and boundaries, Archaeology Ireland, Heritage Guide No. 37.

Harbison, Peter; The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey, Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Henry, Francoise, Irish High Crosses, Three Candles LTD., Dublin, 1964.

Kingdom of Oriel: http://en.citizendium.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Oriel

Lalor, Brian, The Irish Round Tower, The Collins Press, Cork, Ireland, 1999.

Lawless, Nicholas; "Dromiskin Celtic Cross," Journal of the County

Louth Archaeological Society, Vol. 4, No. 4, Dec., 1919/1920, p. 301.

Ireland Reaching Out: http://www.irelandxo.com/node/4280

Louth Heritage: http://www.louthheritage.ie/publications_31_2622865087.pdf

Louth History: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/County_Louth#History

Map of Monastic Ireland, Ordnance Survey Office.

McKeown, Micheal, “Clonmore and a Lost High Cross in County Louth”, Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society, Vol. 26, No. 3 (2007), pp. 336-341

Murphy, Donald, “Monasterboice: Secrets from the Air”, Archaeology Ireland, Vol. 7, No. 3 (Autumn, 1993), pp. 15-17.

Murray, Laurence and Ua Muireadhaigh, Lorcan P.; "Monasteries of Louth," Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society, Vol. 1, No. 1, July, 1904.

O Croinin, Daibhi, ed.; A New History of Ireland: Prehistoric and Early Ireland, “High-kings with opposition, 1072-1166, Marie Therese Flanagan, Oxford University Press, 2005.

Roe, Helen M.; "Antiquities of the Archdiocese of Armagh: A Photographic Survey. Part I The High Crosses of Co. Louth," Seanchas Ardmhacha: Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society, Vo. 1, No. 1, 1954, pp. 101-114)

Roe, Helen, M., Monasterboice and its Monuments, County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society, 2003.

Stubbs, Francis William; "Early Monastic History of Dromiskin, in the County of Louth," The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 7, No. 2, June 30, 1987, pp. 101-113.

Sun and Moon: http://www.learn.columbia.edu/ma/htm/sw/ma_sw_gloss_crucifixion.htm

Sutherland, A.; http://www.ancientpages.com/2018/04/30/lugh-mighty-god-of-light-sun-and-crafts-in-celtic-beliefs/

Termonfeckin: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Termonfe