This page highlights Four Crosses attributed to the 12th century. They include: Cashel (Co. Tipperary), Dysert O'Dea (Co. Clare), Mona Incha, and Roscrea (both in Co. Tipperary).

Twelfth Century Crosses in General

The High Crosses of the Twelfth century are a departure from earlier stages of High Cross carving. Robert Stalley suggests there was a lull in cross making, probably largely in the eleventh century. He states, “A revival of cross carving took place in the twelfth century.” Many were in Munster and at new monastic sites. “The ringed head, when it appears, tends to be more compact, and biblical scenes are largely absent. Instead, the crucified Christ and an ecclesiastic are given great prominence.” (Stalley 42)

Rock of Cashel, County Tipperary

The Monastery

The Rock of Cashel is a large limestone outcrop that rises in a broad and fertile plain. In ancient times and up till 1101 C.E., the Rock was the royal center for the Eoghnacht Chiefs, or Kings, of Munster The name Cashel refers to a circular fort with a stone surrounding wall. [Photo above: The Rock of Cashel, http://yannatry.blogspot.com/2010/07/cashel.html]

In 1101 CE, during a synod held at Cashel, Muirchertach Ua Brian, King at Cashel, gave the rock and surrounding land to the Church in honor of God and Saint Patrick.

At the Synod of Rathbreasail in 1111, the largely monastic organization of the church in Ireland was replaced by the Episcopal system and Cashel became one of two Archdioceses in Ireland, the other being at Armagh in the north.

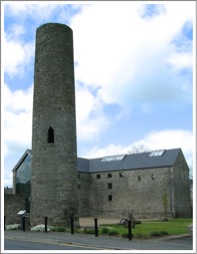

The buildings that now top the Rock of Cashel are from the period of church control. They include the ruins of a cathedral, a chapel, a round tower, and the hall and dormitory of Vicars Choral.

The Cross of St. Patrick stood near the cathedral and was almost certainly carved in the early 12th century. The original is now indoors and a replica stands in the place the cross originally occupied. By making copies and moving the original inside a number of the Irish High Crosses are being preserved for the future.

About the Cross

The Base: The cross of St. Patrick stands on a large stone base not seen in full in these photos. The interesting thing about this base is that legend has it that this stone was used in the crowning of the Kings of Cashel from pre-historic times to the twelfth century.

West Face [right]: Francoise Henry describes the west face. “A very monumental figure of Christ dressed in a long, plain dress reaching to the feet, occupies one side. As H. G. Leask has shown, there may have been small angels carved on separate stones, on both sides of the head of Christ.” (Henry 33) Peter Harbison adds that “on his breast Christ would seem to bear an upright rectangular object (satchel or reliquary?) suspended from around his neck, while beneath the throat there would appear to be a horizontal lozenge-shape, perhaps a brooch.” (Harbison 35) These objects are not readily visible when viewing the cross. If the object is a satchel, it would very likely have been understood to contain the Gospels.

East Face [left]: On the east face of the cross we find the figure of a bishop or abbot. Harbison writes that the figure “raises his right hand in blessing while his left holds a crozier.” (Harbison 34) Traditionally, this figure has been identified as St. Patrick, hence the name for the cross. To my mind, this is almost certainly a bishop as Cashel was the seat of the Archbishop for the southern half of Ireland and was just being established as such at about the time we can presume this cross was carved. In this case it may represent Patrick as bishop of all Ireland, or the office of archbishop in general and the authority of the archbishop of Cashel. It has also been suggested that this figure may represent the founder of the monastery (who may not have been a bishop) or Christ as bishop or abbot of the world. (Harbison 344)

Unique Features: The Cashel cross is unique in that it had vertical stays reaching from the base to the end of each cross arm. Roger Stalley suggests these were structural. (Stalley 44) Françoise Henry suggests these props may represent the crosses of the thieves crucified along side Jesus. (Henry 33) In addition, the Cashel cross, like others from various periods of cross carving does not have a circle around the head.

Dysert O’Dea, County Clare

The Monastery:

According to tradition, St. Tola founded the Dysert O’Dea monastery. The year of its establishment is not clear. However, the Annals of Ulster for 738 refer to the death of St. Tola, Bishop of Cluain. Other dates in the 730’s have also been offered for his death. It is likely, therefore, that the monastery was founded in the late 7th or early 8th century.

In addition to the High Cross, which will be described in detail below, there are additional features of the monastery that are of note.

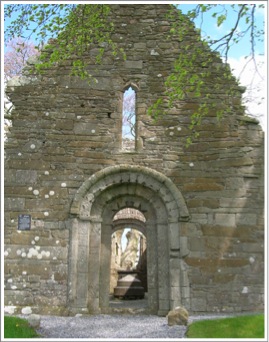

There is a roofless chapel on the site that dates to the 12th century, (see the photo to the right). It has been suggested that this church stands on the site of an earlier church. One highlight of the church is its Romanesque doorway as seen in the photo below. This doorway features 12 human heads carved on the arch. O’Farrell suggests each head was carved as an image of one of the monks who belonged to the community at the time. Each head is certainly distinctive. (O’Farrell, p. 27)

Another feature of the site is the stump of a round tower, which can be seen the photo below.

The Saint:

Little is known of St. Tola. According to one line of thought, he was the son of Dunchad. His family origins may have been in parts of counties Carlow and Kildare. Tola may have been born in that area. He apparently lived the life of a hermit for some years, perhaps in Meath or northern Munster. It is said that he eventually established a monastery there in the 8th century. The tradition that associates him with Dysart O’Dea comes from the “Irish Genealogist, Duald Mac Firbis.” (omniumsanctorumhiberniae)

The Cross:

The cross and its base stand on a tall platform that is just larger than the base, as seen in the photo to the right. According to the inscription on the east face of the base the cross was repaired by Michael O’Dea in 1683 and re-erected by F.H. Synge in 1871. The Commissioners of Public Workds later placed a much larger and lower platform around the whole. The roof of the cross is modern. (Harbison, 1992, p. 83)

East Face:

The base has a panel of interlace, part of which was cut away to create a surface for the inscription mentioned above. See the photo below.

The shaft of the cross contains an image identified as a bishop or abbot as seen in the photo to the right. The figure wears a mitre what was originally pointed. In the left hand is a crozier. The right hand is missing and appears to have originally been an insert. (Harbison, 1992, p. 84) Writing in 1899, George MacNamara simply assumes that the figure represents Saint Tola. (MacNamara, 1899, p. 249) While this identification is appealing, it is by no means certain. What is certain is that more than 350 years after the death of St. Tola, no one knew what he looked like.

The head of the cross has a depiction of the crucifixion of Jesus. Harbison notes that Henry suggested that the figure appears to be more consistent with Christ triumphant than crucified. (Harbison, 1992, p. 84) The head is seen in the photo to the left.

South Side:

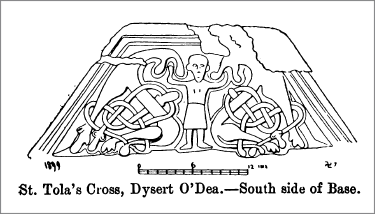

The Base contains a very stylized image of Daniel in the Lion’s Den as seen in the illustration above, right. (MacNamara, 1899, p. 248) Harbison notes that Porter suggests this image may represent Gunnar in the Serpent’s Den. This refers to a Norse legend that would have been known from the 10th century. Deciding between the two identifications of the image calls on the interpreter to read the mind of the artist as both stories have similar content. This image is very different than most of the High Cross images of Daniel in the Lion’s Den.

Below this image is an inscription that was added in the 19th century. It reads: “Re-erected by Francis Hutchinson Synge of Dysart Fourth son of the late Sir Edward Synge Bar and Mary Helena his wife in the year 1871.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 84)

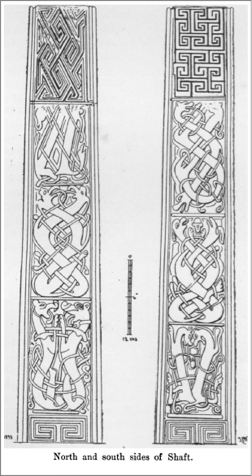

The photo to the left shows both the North and South sides of the cross shaft. The image on the right is the South face. (MacNamara, 1899, p. 251)

The photo to the left shows both the North and South sides of the cross shaft. The image on the right is the South face. (MacNamara, 1899, p. 251)

Harbison describes this side of the shaft as follows:

"S 1: Two animals back to back, their heads turned around to face one another. Each devours the end of an (animal?) interlace which coils around their respective bodies.

"S 2: Two interlaced animals with a human head between their snouts. A narrow band of interlace coils between them.

“S 3: A single animal, now headless because the top of the panel has been damaged. It coils to form a figure of eight, interspersed with a narrower band of interlace.

“S 4: Meander patterns interlinking horizontally and vertically.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 84)

West Face

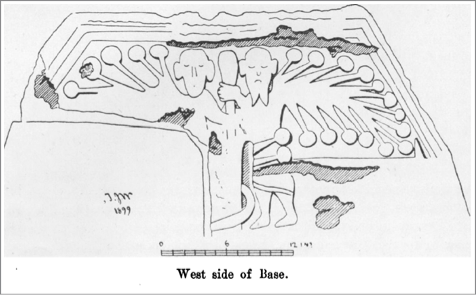

The base has an image that has been interpreted in a number of ways but likely it represents Adam and Eve in the garden.

Writing in 1899, MacNamara suggested the two figures are angels whose wings are “a series of banjo-shaped members, intended, as I take it, to represent feathers.” The angels hold a staff between them. Near their legs is a “sickle-shaped object, to which two ‘feather(s)’ . . . appear to belong.” MacNamara offers two interpretations. It may refer to a legend connected to St. Tola that is now forgotten. Or, it may represent the killing of a badger-monster “securely chained for ever by St. Mac Creiche . . . to the bottom of Loch Broicsighe.” (MacNamara 1899, p. 248-249)

Harbison notes that Roe believed it might represent St. Paul and St. Anthony of the desert breaking bread. This was a fimilar story of the Desert Fathers that would have been widely known in Ireland at the time. (Harbison, 1992, p. 84)

Harbison prefers to interpret the scene as Adam and Eve in the garden. Adam, with a forked beard, is on the right and Eve on the left. The “sickle-shaped object” near their legs is the serpent winding itself around the tree. The “banjo-shaped members” are the boughs of the tree laden with fruit. (Harbison, 1992, p. 84)

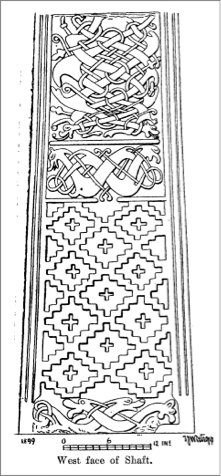

The shaft, like other aspects of the cross, is beautifully illustrated In MacNamara’s 1899 article as seen to the left. (MacNamara, 1899, p. 252)

Harbison describes it as follows:

"W 1: A damaged horizontal panel of animal interlace.

“W 2: Sunken or relief crosses in panels with stepped edges.

“W 3: A horizontal panel of two crossing and interlaced animals.

“W 4: An upright panel of two interlaced animals intertwined with a narrorer ribbon-serpent. The top of the panel has been removed.

“W 5: A panel divided into four quadrants with a circle at the centre, forming the motif of a cross, the expanded terminals of which break through the sides of a central square with bosses at each corner. There are sunken fields of L- and other shapes.” This panel is not illustrated to the left but can be seen in its current very worn condition on the photo below of the head and upper shaft of the west face, and in the illustration from MacNamara, also below.

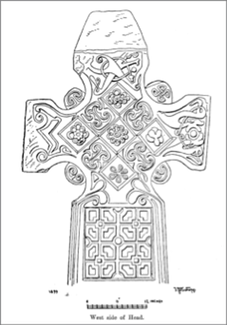

The Head of the cross is best described by MacNamara. “On the west face are five raised lozenges, 5 1/2 inches square, forming a cross, four of them ornamented with rosettes, and the remaining one with superimposed trefoils. Between the lozenges are scrolls of an earlier type, the whole producing a very pleasing effect. The arms are embellished with zoomorphs and the neck with a leaf pattern, but the former are much worn from exposure to the full brunt of the west wind.” (MacNamara, 1899, pp. 251-252)

North Side

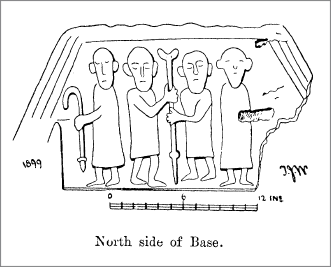

The Base contains a carving that has created considerable speculation. As seen below, it depicts four men, standing at various angles but all facing forward. The two in the center hold “a staff with a tau or crutch head, (MacNamara, 1899, p.249, also the source of the illustration below) or “a staff expanding or blossoming to left and right at the top.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 85) Buckley notes the “boss and sharp point at its lower end.” (Buckley, p. 248) There are two additional figures, flanking the men holding the staff on the left and right. The left hand figure holds what appears to be a short crozier. The right hand figure is missing the left arm. It may have held a staff. Buckley finds this scene to be consistent with two bishops, the outer figures, observing or blessing two monks as they take possession of a piece of land. While Harbison chooses not to speculate on exactly what this scene depicts. He finds some parallels in images of Joseph Interpreting the Dream of Pharaoh’s Butler or a story from the Paul and Anthony cycle of the Desert Father.

While it is speculative, Buckley offers support for his interpretation of the scene with a quote from the annals of the Abbey of Morimond in France. “The abbot, holding a wooden crutch or cross staff in his hand, went forward in front of the brothers . . . all reciting the Psalms. Having got to the place in the forest, or on the moorland, which had been given to them, the abbot planted a ‘cross’ staff thereon, sprinkling the spot with holy water all around and taking possession thereof, in the name of Christ.” He goes on to explain that the bishops of the adjoining area would be present as witnesses. (Buckley, pp. 248-249)

The Shaft, as seen in the illustration above on the left is described by Harbison as follows:

“N 1: Two animals with open mouths and raised paws facing one another, and having a narrow interlace coiling among them.

“N 2: Tow interlacing animals with their heads facing upwards, and with a narrow ribbon of interlace coiling among them.

“N 3: A damaged panel with two animals with broad bodies being interlaced by a narrow ribbon.

“N 4: A fret pattern.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 86)

Mona Incha: County Tipperary

The Monastary and Saints

Information on the history of Mona Incha can be difficult to unravel. The best source seems to be the research in the late 19th century by Canon O’Hanlon. He produced Lives of the Irish Saints.

The photo to the left shows the entire area of the Mona Incha site. It is a very small area.

O’Hanlon's research revealed the following. In the late 6th or early 7th century Saint Cronan, founder of the monastery at Roscrea, to the west of Mona Incha, built a cell on the island. Presumably he used this as a place of retreat. The Roscrea monastery was established in the late 6th century, placing the early religious use of Mona Incha to that same period of time.

The photo to the right shows the west front of the church at Mona Incha with the Romanesque arch.

Some two hundred years later, Saint Elair (Helair) appears on the scene. He is described as “Patron, Anchoret and Scribe of Mona Incha near Roscrea, County Tipperary.” O’Hanlon assigns Elair to the 8th and 9th centuries. He writes, “The death of this Elarius, Anchoret and Scribe, of Lough Crea, is entered in the Annals of the Four Masters, at 802; in those of Clonmacnoise, at 804; in those of Ulster, at 806; but, as we are told by Dr. O’Donovan, it should be 807.” O’Hanlon suggests Elair may have been part of the Culdee movement and refers to his “life of strict observance and asceticism.” (omniumsanctorumhiberniae.blogspot.com)

In 1140 the Augustinians founded an Abbey at Mona Incha and dedicated it to Saint Mary. They had a presence there until 1485. It was during the 12th century the church that remains on the site as a ruin, was built. In the mid 13th century new windows were added to the east wall of the chancel and the south wall of the nave. (thestandingstone.ie)

One legend connected to the site states that any woman attempting to visit the island would die instantly. In contrast any man, while on the island, could not die.

Mona Incha has been given several names. The Standing Stone website refers to it as Inis na mBeo’ or “Island of the living.” The Irish Stones website names it Moin na hinge or “the island in the bog.” The Journal website has the name as Mainistir Inse na mBeo or “the Monastery of the Island of the Living.”

The Cross

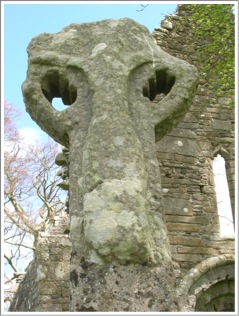

The Mona Incha cross consists of a base and head joined together by a modern concrete shaft. The Irish Stones website suggests a date for the base in the 9th century and for the head in the 12th century. Peter Harbison suggests the two are likely contemporary, both being carved in the 12th century. (irishstones.org; Harbison, 1992, p. 139)

The photo to the left shows the east side of the cross.

The Base

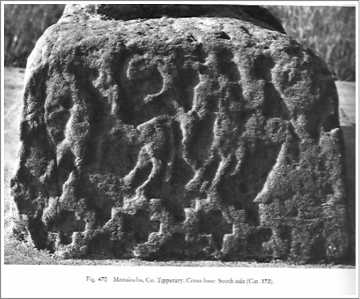

The east face and north side of the base have no decoration. The south side has an image of two horsemen. Between them there is a large figure that may have been speared by the rider on the right. The horses stand on stepped crosses. It has been suggested that this image may reflect the Exodus. The west face of the base has figural sculpture that can no longer be identified. (Harbison, 1992, p. 139)

The photo below shows the south side of the base. (Harbison, 1992, vol. 2, figure 470)

Upper Shaft and Head

The east face of the head, as seen above, bears animal interlace but it is badly worn. The west face, seen in the photo to the right, bears an image of Christ crucified.

The north and south sides both contain animal interlace, also badly worn. “The top of the north side of the shaft has a fragmentary panel bearing the heads of two unidentified figures.” This is illustrated in the photo to the left, at the bottom of the picture. (Harbison, 1992, p. 139 and vol. 2, figure 469)

Roscrea: County Tipperary:

The Monastery and Community

We have the following description of the town of Roscrea, published in the Dublin Penny Journal in 1834, and signed with a simple “B”.

“On my way from Birr I arrived at the summit of a hill, between Drumakeenan and Roscrea, which overlooks the later place. The view from thence struck me with awful recollections of by-gone times. The aged round tower and saxon gable end of St. Cronan’s abbey on the left, and the venerable steeple of the Franciscan monastery on the right, presented on both extremities of the view objects claiming the attention of the antiquary and traveller while the middle space was diversified by the ruins of a round castle of King John’s time, and those of a less ancient one of the days of Henry the Eighth. In the distance, reviving the long dormant spirit of Irish chivalry, appeared Carrickhill, anglice, the Hill of the Rock, from which is taken the title of the Earl of Carrick. The modern church and steeple, and Roman Catholic chapel exhibited a neat but humble contrast to — as they were placed by the sides of — their respective venerable neighbours, the ecclesiastical ruins first mentioned.” (Dublin Penny Journal, p. 268)

This description could virtually be used as a tour guide of significant sites in Roscrea in the early twenty-first century. The photos below show some of these sites. Clockwise from the upper left: Roscrea Round Tower, West Gable of the 12th century Romanesque church (photos by author), Gate Tower of Roscrea Castle and ruins of Franciscan Friary. (wikipedia.org/wiki/Roscrea).

Roscrea is located in a gap in the hills along the ancient road known as the Slighe Dala.

The Saint

Saint Cronan was the Abbot-Bishop and patron of the monastery at Roscrea. He had been living in Connacht but returned to his native area about 610 C.E. He initially settled at what is now Mona Incha, as described above. He seems to have had a cell there. Soon after, perhaps in 610, he founded the Abbey at Roscrea. He established a school there of some repute. Across the years the Abbey produced at least three books: the Book of Dimma which dates to the 8th century, the Annals of Roscrea, and the Rule of Echtgus Ua Cuanain (a tract on the Eucharist) that dates to the 12th century. (encyclopedia.com) The image below is the carpet page for the Gospel of Mark, showing the Evangelist Mark. (http://art-imagery.com/book.php?id=dimma)

The Cross:

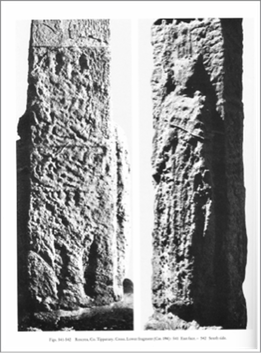

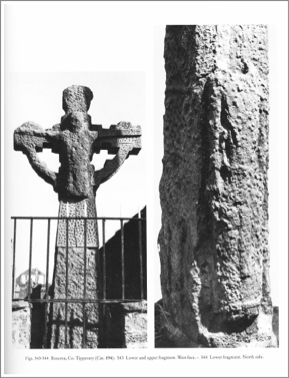

The cross is carved of sandstone and is in two sections, joined by a concrete piece that forms the upper shaft. It stands on a low base that has no carving.

East Face

Shaft: The east face has four panels. The lowest depicts Adam and Eve, apparently clothed and standing by a tree.

The next two panels up are badly eroded, and somewhat difficult to distinguish, but seem to have animal interlace.

The fourth panel, also difficult to define, has a figure that may be a centaur. There are two figures behind. One of them may be playing a Pan pipe.

The image above and left depicts the east face and south side of the cross. (Harbison, 1992, vol. 2, Figs. 541, 142)

Head: The head has a large image of a Bishop or Abbot who holds a crozier in front of himself. (See photo to the right.)

South Side

Shaft: There is an image of a bishop or abbot on the shaft. This figure wears a cloak and holds an in-turned crook in the right hand. (See image above right.)

Head: The majority of the south side of the head is a substitute. At the very top of the head of the shaft, part of the original, there appear to be two human figures.

West Face

Shaft: The shaft on this face of the cross is badly worn. It has been identified in the past as having several panels of animal interlace.

Head: The head has an image of the crucifixion. Harbison describes the image as follows: "Christ, probably bearded and with his hair falling down onto his shoulders, stretches out his emaciated long arms, that on the right being a modern replacement. He is apparently clad in a long robe with a belt at the waist.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 163)

The photo at the left shows the upper shaft and the head of the west face.

North Side

Shaft: There is a large human figure, wearing a long robe that is belted at the waist. The belt-ends can be seen hanging down the front of the figure. The head is missing and was apparently originally separate.

The photo at the right shows the west face on the right and the north side of the shaft on the right. (Harbison, 1992, vol. 2, Figs 543, 544)

References cited:

B., “Roscrea”, The Dublin Penny Journal, Vol. 2, No. 86, February 22, 1834, pp. 268-270

Buckley, Michael J. C., “Notes on Boundary Crosses”, The Journal of the royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 10, No. 3, September 30, 1900, pp. 247-252.

Encyclopedia.com, www.encyclopedia,com/article-1G2-3407709687/roscrea-abbey.

Harbison, Peter; The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey, Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1

Henry, Francoise; Irish High Crosses, Three Candles LTD., Dublin, 1964.

Irish Stones: www.irishstones.org/place.aspx?p=234&i=2.

MacNamara, George, U., “The Ancient stone Crosses of Ui-Fearmaic, County Clare: Part I", The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 9, No. 3, September 30, 1899, pp. 244-255.

O’Farrell, Fergus, “Dysert O’Dea: The Monks of Dysert O’Dea”, Archaeology Ireland, Vol. 18, No. 3 (Autumn, 2004), pp. 26-27.

Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae: http://omniumsanctorumhiberniae.blogspot.com

Stalley, Roger, Irish High Crosses, Country House, Dublin, .1996.

The Standing Stone: http://www.thestandingstone.ie/2009/09/monaincha-abbey-and-high-cross-co.html