This page highlights the Carndonagh Cross at Carndonagh (County Donegal). It includes Background on the cross, a brief introduction to the Monastery, a discussion of the Dating the Cross and a Description of the Cross.

Background

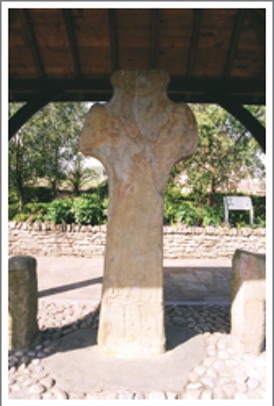

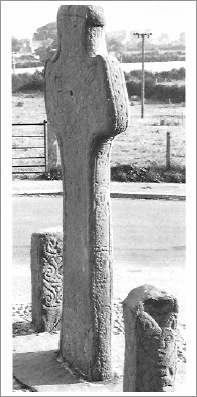

The high cross at Carndonagh is also known as the Donagh or St. Patrick’s Cross. It is located on the Inishowen Peninsula in County Donegal, see the photo to the left. This cross is part of a group of crosses that Peter Harbison identifies as the Northern or Ulster Group. The group includes crosses at Arboe, Armagh, Camus, Donaghmore/Tyrone, Galloon and others. (Harbison, 1992, p. 373)

In the Northern Group, Christ is typically shown wearing “a colobium-like garment which comes to just below the knees.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 274) [In Roman usage, the colobium was typically a sleeveless tunic.] This is true of the Carndonagh Cross, though the garment appears to have sleeves. The Carndonagh Cross is, however, different from many of the crosses in the group in having the crucifixion scene on the shaft of the cross rather than the head.

It is also typical of the Northern group of crosses for the two theives crucified with Jesus to be shown on the arms of the cross. With the crucifixion placed on the shaft of the cross that is certainly not the case with the Carndonagh Cross. It is possible, however, that the theives do appear. See the discussion of the east face of the cross below.

The Monastery

Tradition suggests that a church or monastery was founded in the fifth century by Saint Patrick or one of his followers. Little beyond this tradition is known about the origins or history of the monastery at Carndonagh. Indeed, the supposition there was a monastery there seems to be based in large part on the presence of the Carndonagh Cross. The majority of the Irish High Crosses are related to a monastery. Their presence suggests the monastery in question had achieved a level of prosperity and importance.

Dating the Cross

There is some debate about the dating of the Carndonagh Cross. Estimates range from the 7th to the 10th century. As you will find below, some scholars claim a 7th or 8th century date for the cross. The best example is Francoise Henry. Her dating is reflected in a number of online sites including Megalithicireland.com; Megalithomania.com; tourdonegal.com; and discoveringireland.com. Others, including Peter Harbison and Robert Stevenson lean toward a late 9th or 10th century date. Based on an early date, Henry saw the Carndonagh Cross as one of the earliest of the Irish High Crosses. This distinction is lost if the cross is dated to the 9th or 10th century. Some of the points in the discussion are mentioned below. You can, of course, draw your own conclusions.

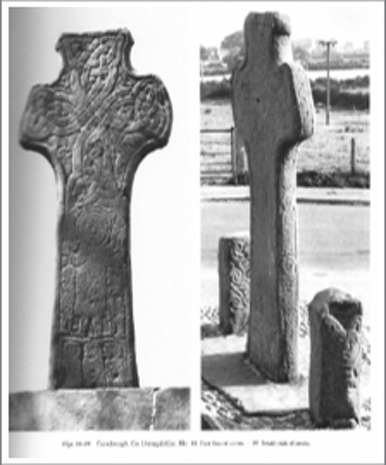

The dating of the Carndonagh Cross has frequently been related to the dating of the Fahan Mura Cross Slab. Harbison lists Fahan Mura among the High Crosses because “it has frequently featured in discussions about the chronology and development of the crosses.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 2) One of the similarities involves the interlace on the cross. Harbison describes the interlace on the east face as follows: “The head of the cross is occupied by an interlaced cross of two broad strands with pointed terminals.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 32) He describes the interlace on the east face of the Fahan Mura cross-slab as “interlacing which has a broad central band flanked on each side by a narrower band.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 88) See the comparative photos below. (Harbison, 1992, Volume 2, Figures 88 and 277)

Francoise Henry, in works written between 1932 and 1967 proposed an early, 7th century date for the cross. Robert Stevenson, in a 1985 article, summarized her thinking as follows: “When Henry formed her views on the date of the Inishowen sculptures she thought that ‘The broad plaited ribbon existed for only a short time in Irish art’, the most notable examples being in the Book of Durrow. [Henry dated the Book of Durrow to the 7th century, but more recent scholarship has dated it to the 8th century. (Meehan, p. 22)] This, together with a kind of terminus post quem of 633 for the Greek Gloria formula inscribed on Fahan’s edge, and the series of primitive-looking slabs along Ireland’s west coast, seems to have been the basis for the 7th century dating. It was supported by her reference to very different Coptic slabs, which however had on them pediments and birds.” (Stevenson, 1985, p. 92)

Another aspect of the debate relates to an inscription on the Fahan Mura Cross Slab mentioned above by Stevenson. The inscription is in Greek and reads [in English], “Glory and honour to Father and to Son and to Holy Spirit.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 360). This is a doxology that was approved by the Council of Toledo in 633. This inscription was taken by Henry and others to confirm a 7th century date. However, the presence of this doxology on the cross-slab cannot limit the time frame of the cross-slab to the 7th century as it continued in use after that. “Kathleen Hughes pointed out that the only other Irish version of the doxology found in the Fahan inscription occurs in a late 8th century penitential.” (Harbison 1992, p. 375)

While Henry and others supported a 7th or 8th century date, Stevenson, Harbison and others support a much later 9th or 10th century date. Based on more recent archeological evidence Stevenson writes, “There seems altogether a stronger case to be made now than in 1956 for the Inishowen sculptures to be part of that widespread but locally differentiated interest in sculpture characteristic of Celto-Scandanavian Cumbria, Man, the Solway shores, Strathclyde and the Isles, spread out over the 10th and 11th centuries. Eclectic and often archaising so that sequential dating is difficult, latterly it was apparently prone to serious degeneration, so much so that some of its Galloway products have also been thought to be ‘primitive’.” (Stevenson, 1985, p. 94)

Description of the Cross

Neither side of the Carndonagh Cross is divided into panels. On both the west and east faces there is roll moulding along the outer edge.

The West Face

The entirety of the west face of the cross is covered with a ribboned interlace composed of a central ribbon with narrower ribbons on each side as seen in the photo to the left. (Harbison, 1992, vol. 2, fig. 87) This ribbon pattern is similar to that on the Fahan Mura Cross-slab discussed above in the section on “Dating the Cross.”

The North Side

The north side of the cross, which is not shown in the photos, is undecorated.

The East Face

On the lowest part of the shaft on the east face there are three figures, turned to the left. They wear long garments. Their position below the scene of the crucifixion led Peter Harbison to identify them as the “Three Holy Women Coming to the Tomb.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 32) This reflects This is a reasonable identification given the fact that in most all of the crucifixion scenes on the Irish High Crosses, Jesus appears to be triumphant rather than defeated. That is, as on the crosses, the scene of the crucifixion implies the victory of resurrection.

The Gospels vary in their description of who came to the tomb on Resurrection Sunday. In St. Matthew we read that it was Mary Magdalene and the other Mary, two women. (Mt. 28:1) In St. Mark it is Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James and Salome, three women. (Mk. 16:1) In St. Luke we read that it was an unspecified number of women who came to the tomb. Those mentioned by name are Mary Magdalene, Joanna, and Mary the mother of James, three named women. (Lk. 24:1-10) In St. John it is Mary Magdalene alone who comes to the tomb. She then runs to tell what she had seen and Simon Peter and "the other disciple, the one whom Jesus loved" came to see for themselves. (Jn. 20:1-4)

While the scene of the women coming to the tomb on Resurrection Sunday is crucial to the story of the resurrection, it is also true that the Gospels record that women who were followers of Jesus were watching the crucifixion itself from a distance. “Many women were also there, looking on from a distance; they had followed Jesus from Galilee and had provided for him. Among them were Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James and Joseph, and the mother of the sons of Zebedee,” three women. (Mt. 27:55-56). Thus another alternative would be to consider these women fit with the crucifixion scene rather than the resurrection scene. In either case the role of women as faithful disciples is lifted up.

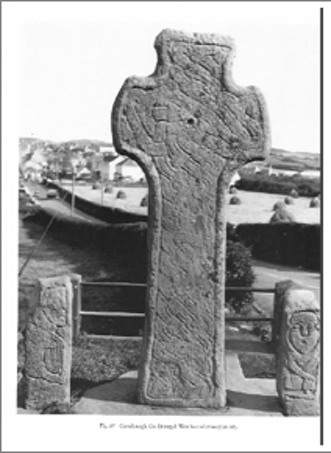

The main section of the shaft offers us an image of the crucifixion. Jesus is clothed in a colobium-like garment that comes to below his knees. He has what appear to be short stubby arms. His arms may be bent at the elbow with only his forearms extended. His head is surrounded by a narrow roll moulding that Peter Harbison identifies as giving a hooded or haloed impression. (Harbison, 1992, p. 32)

There are two figures below Jesus’ outstretched arms and two figures above. The figures below Jesus’ arms have two possible interpretations. They could be taken to be Stepheton and Longinus depicted without their identifying symbols (a stick with a sponge for Stepheton and a spear for Longinus). These are the names given to the characters described in John 19:28-34. Longinus and his spear make their only appearance in the Gospels in this text. Stepheton appears in all four of the Gospels. (Mt. 27:45-48; Mk. 15:33-36; Lk. 23:36-37 and Jn. 19-28-34) Only in Luke is Stepheton identified as a soilder.

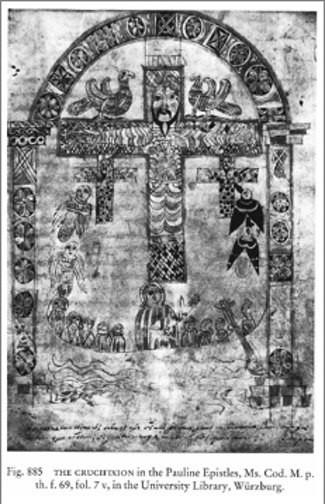

Harbison suggests that these figures may, instead, represent the two theives crucified with Jesus. Here also the Gospel stories vary to some degree about the details. See for example Mt. 27:38; Mk. 15:27-28; and Lk. 23:32-33. There is apparently a bird in a horizontal position above the head of the figure on Jesus’ right and an unidentified figure that could be a bird facing upward above the head of the figure on Jesus’ left. Harbison sees this as comparable to an image found in an 8th century manuscript of the Pauline Epistles that resides in a library it Wurzburg, German. (Harbison, 1992, v.1,p. 32, v. 3 fig. 885)

As seen to the left, this Wurzburg image depicts birds pecking at the thief on the right and angels accompanying the thief on the left. The Gospel of Luke tells us that one of the thieves derided Jesus while the other defended his innocence. The tradition is that the one descended to hell while the other was with Jesus in paradise. (Luke 23:39-43)

In the image to the left, the figures above Jesus’ arms are peacocks, a symbol of resurrection. On the Carndonagh Cross the figures above Jesus’ arms may be taken to represent angels. Harbison points to a comparison with the Crucifixion plaque from St. John’s near Athlone, now in the National Museum in Dublin. This image is seen below. (Harbison, 1992, v. 1, p. 32, v. 2, Fig. 901) Angels on each side of Jesus head are common on images of the crucifixion on the Irish High Crosses.

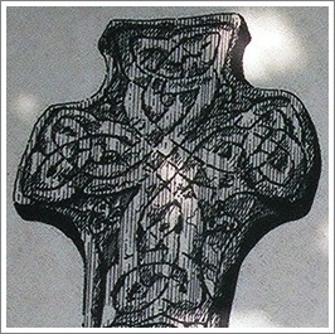

“The head of the cross, seen to the left as a rendering on the interpretative sign at the site, is occupied by an interlaced cross of two broad strands with pointed terminals. At the junction of arms and shaft there are, below, three birds with curved beaks meeting at a point and, above, a three-pointed interlace or triquetra. There is a small boss in the interlace on the arms and the upper limb of the cross.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 32-33)

South Side

On the shaft, see the image above and right, are four figures that appear to be women. On the end of the arm is interlace. Another small figure is on the top of the shaft. (Harbison, 1992, p. 33)

References

Harbison, Peter; The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey, Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Meehan, Bernard, The Book of Durrow: A Medieval Masterpiece at Trinity College Dublin, Town House and Country House, Trinity House, Dublin, 1996.

Stevenson, Robert B. K., “Notes on the Sculptures at Fahan Mura and Carndonagh, County Donegal,” The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 115, (1985), pp. 92-95.