What Is An Irish High Cross?

What makes a cross an “Irish High Cross?” I first became aware of Irish High Crosses on the Isle of Iona in Scotland in 2002. The Iona monastery was founded in 563 by an Irish monk, St. Columba or Columcille (his Gaelic name). The region of Scotland where Iona is located is now known as Argyll. In the sixth century it was in many ways an Irish colony. There are several high crosses at the Iona monastery that could easily be included in the catalogue of Irish High crosses. Traveling on to Ireland I encountered High Crosses at several of the monastic sites we visited. I was impressed by the great variety in the size and the decoration of these crosses. I wanted to know more. Answering the question “what is a High Cross” was not as easy as I expected.

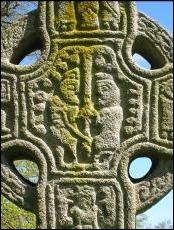

The cross pictured to the left is Saint Martin’s cross located near the Abbey on the Island of Iona, Scotland.

In the following pages you will find some criteria for identifying an Irish High Cross. The first criterion is related to their general shape or physical characteristics. The second, addressed on the next page, relates to the time period in which the crosses were carved.

A Simple Definition

Surprisingly few, if any, writers offer a clear definition of an Irish High Cross. There is a general list of physical characteristics, but there are numerous exceptions to nearly every item on the list. For example, the majority of the Irish High Crosses have a distinctive ring or circle around the head of the cross, either solid or perforated. But there are also examples of crosses without the ring. There are only two characteristics that are always present in Irish High Crosses. First, the cross is made of stone. Second, it is free standing. A free standing cross can be contrasted with a cross slab as illustrated below.

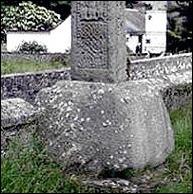

The cross to the left is the Kilamery cross (Co. Kilkenny). It is a free standing stone cross.

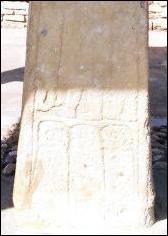

The photo to the right is the Aberlemno cross slab, located in Angus in Scotland. The cross slab is stone but the cross carved on the slab is not free standing.

Regarding the Term “High”

The term “high” in relation to the Irish High Crosses is confusing. Its meaning is unclear. Dorothy Kelly informs us that the term “High Cross” is first found in the Annals of the Four Masters in the year 957. The term was used in the 19th and early 20th centuries along with “sculptured crosses”, “ancient stone crosses”, “early Irish crosses” and “Celtic crosses”. “High Cross” became the dominant term around the middle of the 20th century. (Kelly, p. 55)

Why choose “High” as a descripor. An obvious suggestion is that “high” refers to the height of the crosses. However, the crosses vary greatly in height with one of the shortest being only 3 feet 4 inches (1m) tall and the tallest being about 23 feet (7m) in height. Another possibility is that “high” refers to a practice of holding mass near a High Cross in an outdoor setting. This very likely happened around at least some of the crosses, as most of the High Crosses are associated with monastic sites. But some sites had numerous high crosses placed around the monastic enclosure.

A third explanation of the term “high” is that the High Crosses marked “high” or “holy” places or boundaries of a monastery. Some scholars suggest that at least some of the High Crosses appear to mark the boundaries of the most sacred areas of the monastic enclosure. In some cases these crosses may have marked the outer boundaries of the monastic site. In other cases, as at Clonmacnois (Co. Offlay), there are three crosses in close proximity to the central cathedral but at some distance from the current outer boundaries of the monastic enclosure. These crosses appear to mark the approach to the cathedral, the most holy place in the enclosure. One is found near the northwest corner of the cathedral, a second near the southwest corner and the third, the Cross of the Scriptures, is found directly west of the main or west entry to the cathedral.

Physical Characteristics

Shapes and Sizes: Not all Irish High Crosses look alike. They vary in height, as suggested above, in shape and in decoration. Dorothy Kelly identifies three categories of crosses based on shape. She found 180 crosses complete enough to permit classsification. Of these 28 per cent are unringed, 34 per cent have solid rings and 38 per cent have open work or perforated rings. (Kelly, pp. 54-55) In the photos below, you can observe some of the variety in the Irish High Crosses. The cross to the left is the Market cross at Glendalough (Co. Wicklow) It has no ring and stands a little over 5 feet (1.5m) tall. It has figural carvings. The center cross is the Eglish Cross (Co. Armagh). Only the head of the cross survives. This cross is ringed and the head is solid. It has modest decorative carvings. The cross pictured to the right is the Tall Cross at Monasterboice (Co. Louth). It is also ringed and the ring is perforated. It stands over 20 feet (6m) tall. It has figural carvings relating biblical scenes. It is one of a group of crosses known collectively as “scripture crosses."

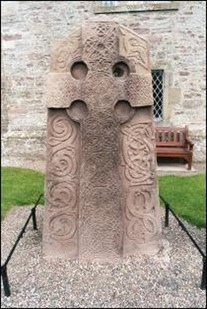

General Characteristics: While Irish High Crosses vary greatly in appearance, as illustrated above, there are a set of typical features. The photo to the right is the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois (Co. Offlay) in central Ireland. It contains all the standard features.

The primary parts of a High Cross include:

- The Base, not actually part of the cross and absent from some of the crosses.

- The Shaft, which is often divided on all four sides into two or more panels. Designs or figural art are placed within the panels.

- The Head, which can be subdivided into the center and the arms. Many of the crosses also feature a ring around the center of the head.

- The cap above the upper arm of the cross is absent from some crosses.

Our physical description of typical High Cross features will begin at the base of the cross and move upward.

The Base: Most, but not all, Irish High Crosses stand on a stepped base. Symbolically, it is said to recall the Hill of Golgotha on which the cross of Jesus stood. (Stalley 1996, 11) Where the base exists, it is typically tapered from the bottom to the top. Functionally, the base provided support for the cross, to keep it stable. The bases shown above are (left to right) the cross of Moone (Co. Kildare) which has a very tall based composed of two truncated pyramids; the St. Patrick’s cross at Carndonagh (Co. Donegal) which has no base and the Drumcliff cross (Co. Sligo) that has a short base that tapers slightly from bottom to top.

The Shaft: The shafts of Irish High Crosses are rectangular in cross section (as opposed to rounded or square) and typically taper slightly from bottom to top.

Many shafts are divided into panels on each side. The panels were used by sculptors for carving geometric designs or figural scenes. To the left we have the Visit of the Magi on the cross of Muiredach at Monasterboice (Co. Louth). The image is in a clearly defined panel. To the right we have the west face of the South cross at Ahenny (Co. Tipperary). It has only one defined panel. This panel is filled with an intricate spiral and interlace design.

The Cross Head: Put simply, where there is a ring, the head of the High Cross consists of the ring, the arms, the top of the shaft, the area within the ring and a cap (not always present).

The Center: Here the horizontal cross beam and the vertical shaft meet. Many of the figural crosses have a crucifixion scene on the west face of the head of the cross. In the tradition of the early church Christ was crucified looking west. But other scenes and designs appear on the west face and, of course, on the east face as well. Below left is the Cross of Muiredach at Monasterboice (Co. Meath). It has a classical depiction of the crucifixion on the west face. On the right is the Kilree Cross (Co. Kilkenny). It has a central boss surrounded by interlace in the center of the west face. Second tier below is the North Cross at Castledermot (Co. Kildare). It has a depiction of the fall of man with Adam and Eve under the forbidden tree on the west face.

The Ring: There are a number of theories about the origin and meaning of the ring that appears on many of the Irish High Crosses. Theory One finds a pre-Christian, Neolithic or Celtic explanation for the ring. The sun was an important symbol for these early peoples. As Christianity became the primary religion, the ring may have symbolically represented the convergence of the sun with Christ, the son and light of the world. In this case, the ring would be related to wheel and disc and cup-in-circle images from pre-Christian times, which are typically interpreted as sun symbols. (Roe 1995, 213)

Theory Two finds the origin of the ring in the fourth century. The emperor Constantine made use of the Chrismon or Sacred Monogram of Christ (the Chi Rho) encircled by the victor’s wreath as a talisman to ensure military victory. (Roe 1995, 213) It was this symbol rather than the cross that Constantine adopted in 312 at the Battle of Milvian Bridge. For Constantine the meaning of this symbol was that Christ provided protection and ensured victory in battle. On the Irish High Crosses this would carry a different but related meaning. Christ is the victor over sin and death and through him Christians share in that victory. To the left is an example of the Chrismon or Labarum.

(Source of image: thefoundationforsacredarts.blogspot.com/ September 2010)

Theory Three suggests that the ring began as diagonal structural supports. These supports would have been on wooden crosses, which almost certainly existed both before and concurrent with the stone crosses. At the very least, an entirely functional explanation of the origin of the circle is unsatisfying. More importantly, Helen Roe writes, “there seems no single instance in the immense corpus of surviving illustrations of the Cross and of the Crucifixion in which the addition of any brace or strut can be discerned.” (Roe 1995, 214)

Regardless of the origin of the ring, not all rings are the same in appearance. Some have been carved through and are referred to as perforate. Others have a solid or imperforate head with the ring and cross in relief.

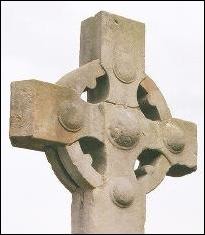

The example to the left is from the Ullard High Cross (Co. Kilkenny). It has a solid ring. The cross is carved in relief. The ring is inset with the spaces between the ring and angles of the cross head more deeply inset.

The example to the right is from the Tynan Village Cross (Co. Armagh). Like the Ullard cross the cross here is in relief. However, the spaces betyween the ring and the angles of the cross head have been carved through in this case.

The example to the left is from the Mona Incha Cross (Co. Tipperary). The cross arms do not seem to have extended beyond the ring in this case. We can also note that the head of the cross is relatively small compared to the shaft.

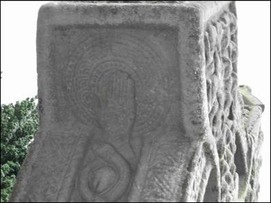

The example to the right is from the Cross of the Scriptures at Clonmacnois (Co. Offaly). It shows an elaborately decorated ring with interlace and decorated roundels or volutes extending in from the ring at the center of each perforation.

The Arms: The arms of the crosses also vary in general shape and in how far they extend beyond the ring, if there is a ring. For example: the arms of the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois (above) angle upward just a bit while most are set at right angles to the shaft. In a few rare cases the arms were designed to accept extensions made either of wood or metal.

The arms of the North Cross at Ahenny (Co. Tipperary), to the left, extend beyond the ring and are fully in relief of the ring so that their shape is clear.

The South Cross at Ahenny (Co. Tipperary), to the right, illustrates that there is typically carving on the ends of the arms.

The underside of one arm of the Cross of Muirdach at Monasterboice (Co. Meath), to the left, illustrates the presence of carving here at well. In this case the Hand of God on the lower side of the arm and two intertwined serpents enclosing human heads on the lower side of the ring.

The top of the shaft and the cap: The top of the shaft typically extends upward beyond the ring. In some cases the carving here is an extension of that on the center of the head. The photo below left, the “Plain Cross” at Kilkieran (Co. Kilkenny), illustrates this. In other cases, there is a separate panel on the upper shaft. The photo in the center below, of the Tall Cross at Monasterboice (Co. Louth), illustrates this. In other cases the shaft does not appear to extend much, if any, above the ring. The Ullard Cross (Co. Kilkenny) illustrates this.

There is often a cap on the top of the cross and, where these occur, they take two primary shapes. (see Richardson and Scarry 25-26) The first shape is domed. This was the shape of the church Constantine had built over the "Holy Seplulchar" in Jerusalem. Thus it was a symbol of the resurrection of Christ. (Richardson and Scarry p. 25) It is worth noting that the dwellings many monks lived in, especially in western Ireland, were also beehive or domed in shape. The symbolism may be the same. Below are two examples of domed caps. The one on the left is on the North Cross at Ahenny (Co. Tipperary). It has a high dome. The one on the right is on the South Cross, also at Ahenny. It has a much lower dome.

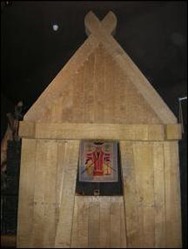

The second style is a gable roof. The two photos left and right of the cross at Killamery (Co. Kilkenny) show this second style of cap. In some cases an outline of shingles is clearly visible. This style resembles “the picture of Solomon’s temple in the illustration of the temptation of Christ in the Book of Kells (fol. 202v)” (Richardson and Scarry p. 25). An image of folio 202v is below right. The source is http://morgangilbreath.com/page/3 January 2014.

It is not surprising that this gable style is also reflected in the typical shape of the roof on early Irish chapels and churches. The two images below are of a model of an early Irish church or chapel that is in the Interpretive Center at Clonmacnois (Co. Offaly).

A third style of cross top does not have any cap at all. The example below is the Clonca Cross (Co. Donegal).