Introduction

The primary purpose of this paper is to introduce the Irish High Crosses of County Wicklow. These are located at Aghowle Lower, Ballintober, Baltyboys, Bray Oldcourt, Burgage More, Delgany, Glendalough, Killegar, Kilranelagh and Kilquiggin. Each cross with be pictured or illustrated and described; and where possible background on the site and the prominent Saint(s) will be provided. As an introduction, this paper also traces the history of human habitation in what is now County Wicklow from the Mesolithic Period to about 1200 CE.

Mesolithic Wicklow: 7000-4000 BCE

The Mesolithic inhabitants of County Wicklow were hunter gatherers who lived in temporary camps and moved with the food supply. Their homes were shelters made of sods, timbers and skins. They used tools made of stone, wood and bone. These included knives, arrows, spears, axes, choppers, chisels, awls, scrapers and picks.

The primary archaeological evidence for human habitation of Ireland in the Mesolithic is in the form of lithic scatter. Lithic scatter is composed of the remnants of the production of stone tools. Such scatter is found in places all along the eastern coast of Ireland. In the 1930’s lithic scatter was discovered in a cave near Bride’s Head, southeast of Wicklow Town. It has been dated to between 5500 and 3500 BCE.

Neolithic Wicklow: 4000-2400 BCE

The Neolithic period in Ireland began with the introduction of farming and domesticated animals. This necessitated a more settled population and the development of new technologies. Land was needed to graze livestock and grow crops. Stone axes were used to clear forests. Pottery was used to store food and querns were used to grind cereals. Dwellings became more permanent and they were constructed of wattle and daub with thatched roofs.

These settled communities undertook the construction of megalithic tombs. These tombs were used as burial places and for other religious ceremonies. These tombs are of three types: portal tombs, wedge tombs and passage tombs. Portal tombs, also called domens, have large capstones, slopped at an angel, and held up by large standing stones. The entire arrangement was then covered with soil and stone, creating a large cairn. A wedge tomb is similar to a portal tomb. The chamber narrows at one end and decreases in height and width from west to east, producing a wedge shape in elevation. There is typically an antechamber separated by a jamb or sill. The walls of the tomb are typically double walled. Often a cairn would cover the wedge tomb. Passage tombs are large cairns resembling a cave with an internal chamber. The passage and chamber are formed by large upright stones capped with large flat stones. The inner chambers, as at Newgrange in County Meath, are often corbelled.

Portal Tombs: Geraldine Stout, in an article entitled “The Archaeology of County Wicklow” identifies three portal tombs in County Wicklow. These are at Broomfields, Glaskenny and Brittas. The Historic Environment Viewer provides a brief description of each of these sites. Each of these tombs has experienced degradation. For example the Broomfields tomb has a backstone and a single upright portal that form a chamber. The other portal and capstone have fallen. (Historic Environment Viewer)

Wedge Tombs: Stout lists four wedge tombs in County Wicklow: Blackrock, Carrig, Mongnacool Lower and Moylisha. To this can be added a fifth wedge tomb first identified in 2010. The Carrigacurra wedge tomb was first identified by Christopher J. Darby and was later excavated by Chris Corlett. The photo, below, is attached to the description in the Historic Environment Viewer.

The wedge tomb is located on the shore of the Poulaphuca Reservoir. It may have been revealed by erosion. “Prior to excavation the site appeared too consist of a burial chamber (0.45m wide and 1m long, open at the south-west) placed off-centre within a U-shaped kerb setting (2.1m north-west/south-east x 2.5m) retaining cairn material.” (Historic Environment Viewer) The tomb is consistent with others that date to the late Neolithic or early Bronze Age. During the Iron Age (760-414 BCE) the site was altered to add a second chamber.

Passage Tombs: The Historic Environment Viewer lists five Passage tombs in County Wicklow. They are: Lackan, Scurlockslea, Blakestown Upper, Tornant Upper and Coolinarrig Upper.

The Coolinarrig Upper tomb is located at the summit of Baltinglass Hill. The tomb “was found to consist of a multi period kerbed cairn (diam. c. 27m) underneath which five structures were identified. . . . within the cairn is roofed with slabs and leads to a chamber (diam. 2m) which contains three shallow recesses. It contains a stone basin with pecked ornament. The photo to the right is attached to the description of the passage tomb in the Historic Environment Viewer. “The finds from the site include the cremations of at least three adults and one child, flint scrapers, Carrowkeel pottery, and bone pins. Finds from beneath the cairn included a stone axe, a flint javelin-head, scrapers an egg-shaped stone, carbonized wheat grains and hazelnuts.” (Historic Environment Viewer)

Bronze Age Wicklow: 2400-600 BCE

The Bronze Age represents the beginning of the use of metals. Initially, copper was used. It was smelted and formed into flat cakes that could be easily transported. Examples of these cakes have been found near the village of Monastery near Enniskerry in County Wicklow. (County Wicklow in Prehistory) Later it was learned that combining tin with the copper formed bronze. Bronze was stronger than copper alone. This led to significant changes in weapons and tools. During this time gold was also worked. One example of a work in gold can be seen at the National Museum of Archaeology and History in Dublin. It is the Blessington lunula, a “flat sheet crescent of beaten gold with quadrangular terminals. It is decorated with finely-incised and complex geometric pattern.” This lunula has been dated to 2400-2000 BCE. (http://rmchapple.blogspot.com/2019/05/co-wicklow-archaeological-objects-at.html) See the photo below left.

As the Bronze Age progressed, megalithic tombs such as wedge tombs were replaced by cist burials. In this type of burial the body or cremated remains were placed in a stone lined box in the ground and covered by a lid. In some cases a cairn of stone was placed over the top.

Bronze Age ceremonial sites included stone circles, standing stones and rock art. An example of a stone circle in County Wicklow is the Athgreany circle just south of Hollywood. It is composed of 16 granite stones, some two meters high. The circle is about 22 meters across. Just to the north is a standing stone that appears to be an outlier of the circle. (https://visitwicklow.ie/item/pipers-stones/) Other stone circles an be found at Blessington, Ballyfoyle, Carrig, Sroughan, Boleycarrigenn and Castleruddery. A standing stone at Ballintruker stands more than 10 feet tall. Examples of rock art can be found north and south of Ballykean House near Rathdrum. (Stout, p. 129)

Dwellings during this time became larger but continued to be built of wattle and daub with thatch for the roofing. Farming and animal husbandry continued and the diet included both grains and meat. Some cooking seems to have taken place in fulacht fiadh.

Iron Age Wicklow: 600 BCE to 400 CE

Archaeological evidence for the Iron Age, in all of Ireland, is vague. A chapter entitled “Iron Age Ireland” in A New History of Ireland: Prehistoric and Early Ireland, written by Dr. Barry Raftery offers some insights. We associate the Iron Age in Ireland with the arrival of the Celts. What is known is that by about 500 BCE Ireland was on the threshold of the Iron Age. (Raftery, p. 137) Artifacts of bronze, gold and iron began to show evidence of influence from La Tene Europe by 300 BCE. By the middle of the Iron Age, about the end of the last millennium BCE, numerous examples of personal adornment were being produced. These included necklaces and bracelets of glass and bone beads. The most spectacular of these were the gold torcs that were worn around the neck. Other personal grooming implements were also present such as mirrors, tweezers, bone combs and iron shears (possibly for cutting hair). (Raftery, p. 150)

Travel was frequently by horseback and trappings for horses were produced of iron. Household goods were also common, including loom-weights, domestic pottery, drinking vessels, bowls and cups. “Drinking and feasting appear to have been important aspects of life among the Celts.” (Raftery, pp. 154-5)

Hillforts, that began to be built in the Bronze Age, continued through the Iron Age and into the early Medieval. The Hillfort at Rathgall in County Wicklow is one example of this overlap. In an article for visitwicklow.ie, Barry Raftery described this hillfort. It sits on the edge of a ridge and has four concentric stone walls. The inner circle is 15m wide. The site may date to 800 BCE, toward the end of the Bronze Age. There is also evidence for later metal work. The residents were “casting large quantities of bronze weapons and tools. Other finds included glass, bronze and stone objects, clay moulds, gold and glass beads and other artefacts.” (visitwicklow)

Hillforts appear in three varieties. There were those with a single line of defense; those with two or more lines of defense, such as Rathgall; and promontory forts both inland and coastal. In these latter forts only one of the four sides of the site needed a built defense. Raftery reminds us that dating these hillforts can be difficult as they span a long period of time. (Raftery, pp. 163, 165)

Wealth during this time was typically measured in cattle. Writing in an article in Archaeology in 2020, Jarrett A. Lobell described the practice of cattle rustling. “It was not enough for medieval Irish lords to own cows, they also had to steal them. ‘Stealing cows was important in this society,’ says archaeologist Daniel Curley of the National University of Ireland Galway. ‘It was a ready source of wealth, a light to opponents’ honor and power, and a pseudo-martial sport.’” (Archaeology, 2020) While Lobell and Curley are describing the early medieval period, when the Cattle Raid of Cooley was written, I am assuming here that this was a reflection of practices that reached back into the Iron Age.

Burials during this time included both cremations and inhumations. Graves were sometimes covered by mounds or ring-barrows.

Early Medieval Wicklow: 400 to 1200 CE

The defining characteristic of the Early Middle Ages in Ireland was the arrival of the Christian faith. More on that when we consider ecclesiastical history below. The most prosperous farmers lived in circular raths or ring forts. “Each was a well-fenced farmyard for ordinary agricultural purposes and offered minimal defense against thieves and raiders in more disturbed times.” (O’Corrain, p. 551) Most had souterrains for storage and refuge. Within the enclosure were sheds and houses. The rest of the interior was a farm yard with hens, dogs and pigs roaming free. “In the seventh and eighth centuries land was owned and farmed by the derbfine, a four-generation agnatic lineage-group which was the family for legal purposes.” (O’Corrain, p. 153) The primary grain crops were oats, barley and rye. Few vegetables were grown and apples were the only fruit that was cultivated. Stock-raising and dairying were so dominant that “land itself was estimated in terms of the number of cows it could feed.” (O’Corrain, p. 568) Pigs and sheep were also raised. Food shortages occurred periodically and contributed to migration and an increase in violence. Monastic sites and towns, with income from the faithful, could accumulate surpluses which led to attacks on monasteries in times of shortages.

Life was difficult and often short with a life-expectancy of about 40 for the majority. Epidemics occurred with regularity during the late 7th through the early 9th centuries. (O’Corrain, pp. 578-9)

Politics in and around County Wicklow

In the larger province of Leinster during the 5th century (400-500 CE), the Dal Messin Corb were a primary power in the northern half of Leinster while the Ui Bairrche were dominant to the south. The Dal Messin Corb held territories north of the Wicklow Mountains and in the plains of what is now County Kildare. They were involved in struggles with the Southern Ui Neill who were expanding into northern Leinster and eventually eliminated the Dal Messin Corb from political power. In what is now County Wicklow at about 500, the Rootsweb maps of Ireland’s history in Maps indicate that the Ui Mail were one of the largest tribes.

In Leinster, in general, in the 6th century (500-600 CE), the Dal Messin Corb lost political power in the north of Leinster. They were replaced, for a time, by the Ui Mail, who in turn were eventually ground down by the Ui Neill. The Ui Mail were active in what is now County Wicklow. The Ui Bairrche were all powerful in the center of Leinster, including parts of County Wicklow, and the Ui Cennselaig had largely taken power in the south. In County Wicklow around 600 the Ui Garrchon had pushed, or been pushed south into what is now County Wicklow and a tribe called the Ui Enechglaiss were also prominent in Wicklow.

During the 7th century (600-700) the Ui Dunlainge and Ui Bairrche were powerful in the west of Wicklow into what is now County Kildare. Circa 700, the Ui Dunlainge were the main kingdom in what are now counties Wicklow and Kildare, and parts of Dublin and other surrounding counties.

The 8th century (700-800), saw the Ui Garrchon and Ui Enechglaiss active in east Wicklow, the Ui Dunlainge a lesser kingdom in the greater Wicklow area and the Ui Chennselaig in power in the south of Leinster.

By the end of the 9th century (800-900), the two primary powers in Leinster were the Ui Dunlainge in the north and the Ui Chennselaig in the south. The Ui Garrchon and Ui Enechglaiss continued to be active in east Wicklow

Circa 950, the Vikings dominated much of what is now County Dublin. What is now County Wicklow also seems to have had a Viking outpost in the area of what is now Arklow. Three different Annals report that in 835/36 “Kildare was raided by foreigners of Inber Dee (Arklow?), and half of the church was burned by them.” (AFM 835.12 quoted in Downham) The name Arklow is derived from Arnkell, a Viking leader and lag (low) referring to a low area of land. It was also known in Irish as Ihbhear De, from the River Avonmore’s old name, Abhainn De. The Ui Dunlainge were the major kingdom to the south and west of Dublin and the Ui Cennsaliag continued to be the dominant kingdom in the southeast of Leinster with two additional Viking settlements to their southeast, at Wexford, and to their southwest, at Waterford. The Ui Garrchon and Ui Enechglaiss continued to be active in east Wicklow.

Circa 1000, Brian Boru had established control over much of Ireland, including Leinster. Mael Morda mac Murchada of Leinster rebelled against Brian in 1012. The next year, Brian attacked Leinster. His son Murchad focused on the southern half of the province. After laying siege to Dublin, Brian was forced to retreat due to lack of supplies. The next year, 1014, at the Battle of Clontarf, Mael Morda and his allies were defeated and Brian died in the battle.

The end of our historical survey takes us into the 12th century. Diarmait mac Murchada became king of Leinster in 1126. In 1166 he was ousted from his kingship by a coalition of other Irish kings and some Leinster princes. He fled to England and with support from Henry II he recruited an army to retake his kingdom. This gave Henry II an opportunity to gain influence in Ireland and led to the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169, under Richard FitzGilbert de Clare, better known as Strongbow.

Ecclesiastical History

The Christian faith probably entered Ireland as a result of trade connections with Roman Britain and the Mediterranean world. This occurred as early as the late 4th and early 5th centuries. In 431 the Pope commissioned Bishop Palladius to go to the Irish believers in Christ. His work was in the southeast and was probably more extensive than has often been reported, as the supporters of St. Patrick sought to minimize his role. He was further eclipsed by the development of the cult of Brigid of Kildare. Palladius seems to have had four other bishops who joined him in 439. They were: Auxilius, Secondinus, Iserninus and Benignus. Their efforts were also focused on Leinster. As will be seen below, the monastery at Tourney, in what is now County Wicklow, is the only church or monastery purported to have been founded by Bishop Palladius.

Christianity had some characteristics in common with Celtic paganism. There was believe in another world, prophetic powers of druids and saints, and the performing of miracles and magic. “The doctrine that wrongdoing was an offense against this new, all-powerful God which could result in eternal damnation if not forgiven, was not easy to accept. However, this was also a loving God who forgave those who truly repented, no matter how many or how serious their sins. The Christian faith did not overtly, exclude anyone from salvation; all people of whatever stratum of society could be saved.” (Culleton, p. 69)

The church in Ireland underwent a change in the 6th century. Up to then, that is from about 431 when Bishop Palladius began his mission, there were churches led by non-monastic bishops and clergy. The same was true in the north where the ministry of St. Patrick was centered. “Then, about the middle of the sixth century, the most influential people in the church took up the monastic life. If we are to believe the hagiographical tradition the vast majority of these early abbots belonged to the aristocracy.” (Hughes, p. 311 in O’Croinin)

Kathleen Hughes, who wrote prolifically on the Irish Church, offered the following summary of the first 400 years of Christianity in Ireland in A New History of Ireland: Prehistoric and Early Ireland, Daibhi O’ Croinin editor in a chapter titled “The church in Irish society, 400-800”.

“The first hundred years or so of the church in Ireland was a period of missionary effort, when princes and people were gradually converted by clergy trying to hold themselves separate from the world. Then came the great plague of the mid sixth century and the development of monasticism. Families set up their own monastic houses in a system quite different from the episcopal system of the early church. This constitution came into closer contact with secular men of learning, and ecclesiastical and secular law cohered, so that the church was fully integrated into secular life. The increasing secularization of monasticism led to a revival of ascetic religion in the later eighth century. By 800 the Irish church was in a very healthy condition, rich and respected, with ascetics leading the spiritual life of the country and among Ireland’s finest representatives of learning” (Hughes, p. 320 in O’Croinin)

In a later chapter in A New History of Ireland, “The Irish church, 800-1050,” Hughes writes that while the vikings damaged churches and stole church property, the churches typically recovered quickly and monastic life went on. She goes on to note that by the 10th century, the vikings were Christians and were giving their sons Christian names. Because abbots and bishops were of the same class as secular nobility, there was a convergence of interest between ecclesiastical and secular lords. Major monasteries were becoming dominant over smaller foundations, thus consolidating power, as was happening in the secular arena. (Hughes, pp. 644-647 in O’Croinin)

There are three important Saints associated with what is now County Wicklow.

St. Finnian of Clonard: St. Finnian was originally from Leinster. He is most closely associated with the monastery at Clonard, in County Meath. However, the first monastery he is recorded as founding was at Aghowie, in what is now County Wicklow. Finnian is remembered as the teacher of the Twelve Apostles of Ireland. These included St. Ciaran of Clonmacnoise, St. Brendan the Navigator and St. Columba.

St. Kevin (Coemgen) of Glendalough: St. Kevin was born around the year 500 CE. He first retreated to Glendalough, the Glenn of the two lakes, as a hermit. Drawn to him because of his piety, followers led him to establish a monastery at the Upper Lake. This happened some time in the 6th Century. More on Kevin below in the discussion of Glendalough.

Lorcan Ua Tuathail (St. Laurence O’Toole) became Abbot of Glendalough in 1154, at the age of 26. Laurence was a reformer, bringing the monastery at Glendalough in line with Frankish-European traditions. He invited the Canons of St. Augustine to Glendalough and led the construction of St. Saviours monastery, east of the Monastic City for them. In 1162, still only 32 years of age, Laurence became Archbishop of Dublin. He was Archbishop at the time of the arrival of the Normans. More on Laurence below under the discussion of Glendalough.

There were ten early Christian monasteries in what is now County Wicklow, according to: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_monastic_houses_in_County_Wicklow

Aghowie, early site, founded by St. Finnian of Clonard

Ballykine early site, founded by a brother of St. Kevin?

Bray, early site

Delgany early site, founded by St. Kevin (Coemgen) of Glendalough for St. Mogoroc (Curarog)

Ennereilly, early site, founded pre-639

Ennisboyn, eearly site

Glendalough early site, founded 6th century by St. Kevin (Coemgen)

Killaird, early site, nuns

Rathnew, early site, founded pre-779, patronized by St. Ernin

Tourney, early site?, founded by St. Palladius?

Of these ten sites, high crosses or cross bases appear at four: Aghowie, Bray, Delgany and Glendalough. At Bray there is a cross base. At Glendalough there are numerous crosses. Each of these sites will be addressed in greater detail in the section on the High Crosses of County Wicklow below.

There are additional high crosses in County Wicklow, some of which may not have been associated with a monastery. At Ballintober there is an abandoned cross that broke in the process of being carved. A cross at Ballysize Lower may have been a grave marker and is known as the “Bishop’s Grave.” A cross in the graveyard at Baltyboys may, according to Christiaan Corlett, suggest the presence of a church there in the 10th century. At Killegar there is the top of what seems to have been a Tau Cross. It is associated with the ruins of a church. At Kilquiggin, in the grounds of a graveyard, there is a cross base and the head of a cross. It is unclear whether this relates to a church or a possible monastery. Each of these sites and their crosses is also discussed below.

Aghowle Lower

The monastery at Aghowle (meaning field of the apple trees) was established in the 6th century by St. Finnian. It is recorded that he erected a “Teampall Mor’ or big church because there were a large number of monks in the community. This early church would have been of wood and the monks would have lived in beehive cells. The present stone church on the site was constructed around 1100. (Rath Hillfort brochure)

The undecorated cross here stands just over 9 feet in height and has a wingspan of over 5 feet. It is carved of granite and has an imperforate ring. It stands on a pyramidal base that is about 18 inches in height. Undecorated panels seem to be carved on the underside of the ring. (Harbison, 1992, p. 10) This may suggest that the cross was intended originally to be decorated, and remained unfinished.

Just at the foot of the cross is a large, trough-like font that may be an example of an early Christian baptismal font. St. Finden’s Cross can be dated to 900-1000 and the font may be contemporary. (Corbett, blog)

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 45 5 D. Aghowle Church is marked on the Atlas map. Located south of the R725 about 6km east of Tullow. See the map to the right.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Ballintober (abandoned)

The Ballintober cross was never completed. It broke when turned on one side for carving. In spite of this it does offer insight into how the High Crosses were created. The cross was to be carved from one piece of granite. The shape was roughed out on one face and the sides. The cross would have been large, with a height of over 16 feet. The arm span would have been more than six feet. When the mason turned the cross in order to prepare to shape the back face of the cross the shaft snapped along a fault in the stone that was not visible from the front. One possible dating of the carving of the cross is the 10th century. This is by no means certain and it may be much more recent. (Corbett, 2011, pp. 26-29)

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 45 1 D. East of Hollywood about 4km along R756 you will come to the L8347. There will be a sign for the Abhainn Ri Farmhouse & Cottages there as well. Drive to the Cottages and across the street there is a style into the field where the cross is located. See the map to the right.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Ballysize Lower Cross

Henry Crawford described a cross at Hollywood, Ballysize Lowerk, Poulaphuea. He described it as “a rough, plain granite cross, 4 feet high, with part of the top broken. It appears to be on the site of an ancient burial-place.” (Crawford, p. 234) The Historic Environment Viewer adds that this unringed granite cross is known locally as the “Bishop’s Grave.” It adds that “there is an equal armed cross within a circle inscribed on the lower E side of the shaft.” (Historic Environment Viewer, County Wicklow, “Cross”, compiled by Gearoid Conroy and Matt Kelleher.)

It is unclear as to the date of this cross and as it is not listed in the Historic Environment Viewer under “High Cross”, but can be found by searching instead for “cross”. It may be outside the typical time frame of 1200 or earlier for the High Crosses.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 45 1 D. The cross is located in the Ballysize townland. Ballysize can be reached from the N81 just north of the exit to Hollywood. Coming from that direction you will come to a derelict white two-story house with a number of large farm buildings just past the house. The cross can be reached through a farm gate adjacent to the most northerly farm building. It is located about 100 yards to the left. See the map to the right.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Baltyboys Cross

Christiaan Corlett recently discovered a stone cross in the old graveyard at Baltyboys in County Wicklow. (http://www.christiaancorlett.com/blog/4564514201) “The granite cross measures 56cm across, while the upper transom is 28cm wide and 19cm high above the cross arms. The shaft is slightly wider than the upper transom, measuring 33cm across.”

Both faces are decorated by domed, circular bosses enclosed by rings. The two are of slightly different sizes. These features relate the cross to those at Ballymore Eustace and Burgage, suggesting a 10th century date for the modest Baltyboys cross.

The presence of the cross supports conjecture that there was an early medieval church at this sight.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 45 1 D. The R758 will take you to a turn off onto an “L” road on the left. The graveyard the cross is located in is indicated by the lower of the two black dots. See the map to the left.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Bray Oldcourt

This cross base was found in 1780 “buried in a bank on the west side of the road from Bray to Oldcourt.” (National Monument Viewer) Mason suggests that the original site of the base may be related to a possible monastic site near a place called Kilbride, to the west of Oldcourt and near Blessington. (Mason, p. 27)

This cross base was found in 1780 “buried in a bank on the west side of the road from Bray to Oldcourt.” (National Monument Viewer) Mason suggests that the original site of the base may be related to a possible monastic site near a place called Kilbride, to the west of Oldcourt and near Blessington. (Mason, p. 27)

The base is just over four feet in height and approximately two and one half feet at the base. There is a mortice in the center of the top of the base.

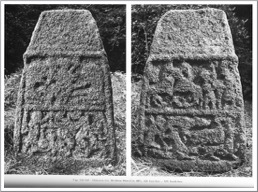

(Photos from Harbison, 1992, Figs. 528-530; description below from Harbison, p. 159)

The lower two-thirds of the East, West and South faces have roll-moulding and each is divided into two panels separated by a bar.

East Face: The lower panel has two images: left and center is St. Michael Weighing Souls. On the right side is an image of David slaying the lion. The upper panel shows Daniel in the Lions’ Den. This is the photo above and left.

South Face: The lower panel has a hunting scene that has the image of a person with a stick on the left. There is a possible dog below and others in front. They are hunting two animals to the right. The lower of these animals seems to be a lion at bay. The upper panel right shows two figures, a tall figure on the extreme right moves toward a shorter figure on his left. Something like an upright stick is between them. On the left side of the panel are two animals with crossed necks. This is the photo above right.

West Face: The lower panel has two animals approaching each other. A knot of interlace is between them. The upper panel left has an image of Eve Giving the Apple to Adam. On the upper right is a horseman moving right. This is the photo alone to the left.

Based on the style and materials, this base compares well with the granite crosses of the Barrow Valley at Moone and Castledermot. The base may be dated to the ninth or tenth centuries. (Mason, p. 27-28)

Getting There: This cross-base is on private property and is not available for viewing.

Blessington/Burgage More

There are two crosses at Blessington that were moved from Burgage More around 1940 due to the creation of a lake. Burgage More was a medieval settlement that sat on the banks of the River Liffey. “Medieval documents tell us that Burgage More was part of the lands of the Bishop of Glendalough in the 12th century. The ruined church is testament to the presence of a significant ecclesiastical community. (Wicklow Heritage)

St. Mark’s Cross

The cross pictured to the left is known as St. Mark’s Cross. This cross stands just over 14 feet in height and has extremely long arms. The ring is imperforate and outlined by a raised rib. Each face of the cross has a boss in the center of the head. A fragmentary tenon at the top of the shaft raises the possibility that there was a “roof” on the top. "Up until the 19th century, it was also known as St Baoithin’s cross. He was a saint from Kildare who died in the early 7th century and whose feast day falls on December 13th.” (Wicklow Heritage)

A date of 1400 is carved on the base which appears to be ancient. (Harbison, 1992, p. 28)

Cross-Head

The cross-head pictured to the left also has an extremely long arm on the right. The left arm is broken off. The original arm span would have been about five feet. The cross is now four and one half feet high. The ring is imperforate and like St. Mark’s cross it has a fragmentary tenon on the top. (Harbison, 1992, p. 28)

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 35 5 D. From the R411, the crosses are in a graveyard to the east of town. See the map to the left.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Killegar

This cross-head is in the ruined church at Killegar. This is the upper part of T-shaped granite cross that measures about 1.5 feet across the arms and is about 10 inches in height. It is decorated in the center of the head with a raised boss that is inside a raised ring.

It is possible the cross dates from the later medieval period but Harbison includes it in his listing. (Harbison, 1992, p. 128)

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 36 5 G. Turn to the west 2km north of Enniskerry (on the right side of the road at that point there is a signpost that indicates the distance). Turning up that winding road it is about 0.5km to a house named “Capistrano”. The next gate to the left from puts you into a farm road. The walk down the road is less than 1km. Follow that farm road and take a right at the only fork.

The map to the left is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

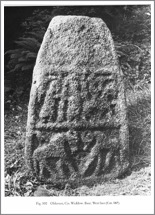

Delgany Cross

The shaft of a cross is located in the old churchyard at Delgany. The shaft is a little over six feet in height. On the south face, shown in the photo to the left, there is an inscription and above it there may be a decorated panel.

The inscription asks for prayers for two different people. The name of the first cannot be discerned. The name of the second appears to be Odran who was a wright (sair) and may have carved the inscription. (Harbison, 1992, pp. 357-358)

The two sides, shown in the photos to the right, each have a central panel that is recessed. There is no evidence of other decoration.

The north face indicates that the cross-shaft was not flattened on this side, perhaps due to a flaw in the stone. See the photo to the left.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 46 1 G. From the N11 take exit 10 and follow the R762 east toward Delgany. After about 1km you will see the entrance to the old graveyard on the left. It is just beyond “The Delgany”, a bakery and cafe. See the map below.

CThe map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Kilquiggin Cross

All that remains of medieval Kilquiggan is a battered High Cross known locally as 'The Crush’. (Find a Grave) The cross is mentioned by Harbison. He wrote: “Lying beside a granite base at the edge of a wooded area near the village of Kilquiggin is an imperforate granite cross-head. It measures 70cm across the arms, is 50cm high and 16cm thick. On the face illustrated here there is a triskele in false relief, while on the other face there is a round flat undecorated boss.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 132)

Getting There: See Road Atlas page page 45 5 D. Finding Kilquiggin village and an old graveyard there is straightforward. Go past the graveyard to the east and take the curve shown on the map to the left. The next short road to the right is the drive to a farm house. From there you can enter the fields where the cross-head and base are located. They are in the second field back to the west.

The maps above are cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Kilranelagh Cross

This cross was noted in 2005 following the clean up of the Kilranelagh graveyard. Corlett describes it as just over 3 feet in height and about 2 and one half feet across at the arms. Near the center of the head is a raised boss that is similar to the high crosses at Ballymore Eustace in Co. Kildare, and Burgage in Co. Wicklow. Based on this, Corlett suggest this cross may be of early Christian date. (Corlett, 2005, p. 140)

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 45 C/D 3. From Baltinglass take the R747 southeast to the intersection with the L3273 to Rathdangan. At the T go left. In less than 1 mile there will be a road to the right. Follow this for a little over 1000 feet and take a left on a very narrow road. The graveyard is at the end of the road.

The Map is cropped from Google Maps.

Resources Consulted

Corlett, Christiaan, “Two Recently discovered Crosses from Co. Wicklow”, The Journal of the royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 135 (2005), pp. 140-144.

County Wicklow Heritage: http://countywicklowheritage.org/page_id__16_img__187.aspx

Harbison, Peter, 1992, The High Crosses of Ireland: an Iconographical and Photographic Survey, 3 vols. Dublin. Royal Irish Academy. Bonn. Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH.

Glendalough Crosses

The Monastery

The story of the founding of Glendalough monastery is told below as part of the life of St. Kevin. The exact date of founding is not known, but we do know that Kevin’s death is recorded as 618. That suggests the monastery was probably founded in the second half of the sixth century. The photo below right shows the Monastic City, developed after the time of Kevin, as seen from the south.

The Irish Annals record some events in the history of the monastery. (Walsh, 716-17)

770 Glendaloch was destroyed by fire830 the Danes plundered and sacked the abbey

833 the Danes repeated their ravages

835 the Danes again burned the abbey

866 Abbot Daniel died

908 Cormac Mac Cullinan, who was slain in battle, bequeathed an ounce of gold and another of silver to this abbey

927 Dolish Mac Sealvoy, abbot of Timoling, and lecturer of Glendaloch died

953 Moel Jonmain, philosopher and anchorite of Glendaloch died

955 Anchorite Dermod died

957 Anchorite Martin died

965 O’Manchan, anchorite and director of Glendaloch died

972 Abbot Coirpre O’Corra died

977 The Danes of Dublin plundered the town and abbey

983 the three sons of Kearval Mac Lorean plundered the termon-lands of St. Kevin, but through the immediate intercession of that saint, they met their merited fate, and were all slain on the day they committed the sacrilege.

1176 the English adventurers plundered Glendaloch

1177 a flood ran through the city, by which the bridge and mills were swept away, and fishes remained in the midst of the town

1197 Thomas was abbot

And one entry that lies outside our period of interest but is significant.

1398: the English forces destroyed the city of Glendaloch. It is now a city of ruin and desolation, and its fame is not only known through its history, and will be celebrated, when even the vestiges still remaining, of its several churches, and of its former greatness, will totally disappear.

St.Kevin

There are several Lives of Kevin, each of which gives him a regal lineage. They also record miracles related to his birth and childhood. One story suggests that eventually he was given into the charge of three “holy elders” (Barrow, p. 52); Eogoin, Lochan and Enna. In the midst of a period of study, Kevin adopted the life of a hermit. It was in his search for a place of solitude that he found Glendalough. There he set himself up in the hollow of a tree. He was eventually found there by his teachers and returned briefly to their monastery. Later he was sent to a Bishop Lugidus, who ordained him as a priest and sent him off with other monks to establish a church. The original location for this church was a place called Cluainduach. They soon abandoned this location and moved to Glendalough. (Barrow, pp. 52-54)

The Latin Life states that Kevin founded “a great monastery in the lower part of the valley where two clear rivers flow together.” (Barrow, p. 54) This would be the location of the present Monastic City. It then suggests that Kevin himself soon retired to the upper lake where he resumed his life as a hermit. His base may have been at Temple na Skellig on a “narrow ledge on the south side of the Upper Lake.” (Barrow, p. 54) The photo above left shows the beauty of the Upper Lake.

Another story suggests that the early monastery was close to the Upper Lake and moved west to the site of the Monastic City where there was more space available for the growing community.

According to the Lives, Kevin had a special relationship with the wild beasts of the area. One story tells us that while praying in his beehive hut above the Upper Lake a bird built a nest in one of his hands. Kevin remained in that position of prayer until the bird’s egg hatched and the young bird flew away.

Kevin seems to have had at least three places of shelter near the Upper Lake. One was Teampull na Skellig, another was the cave called Kevin’s Bed near and above Teampull na Skellig. The third was an oratory of twigs on the north shore of the lake. Barrow does not mention Kevin’s cell above the Upper Lake, mentioned above. Kevin lived out his life at Glendalough and according to the Annals of Ulster died in 618. (Barrow, p. 57)

St. Laurence O’Toole

A second significant saint related to Glendalough was Laurence O’Toole. He was born in 1123 to a ruling family. After some difficulty in his early life he was given into the care of the Bishop of Glendalough. While there Laurence chose to enter the Church. At a young age he was chosen abbot at Glendalough in 1153. He ruled with “great virtue and prudence and strict enforcement of the rules” (Barrow p. 58) for about nine years. Following that, in 1162, he became Archbishop of Dublin.

It was during the time of Laurence O’Toole that St. Saviour’s monastery, located west of the Monastic City was built. It is a 12th century foundation.

The Crosses: Peter Harbison listing

Peter Harbison notes that “Glendalough has more crosses than any other site in the country, but as a number are rather small and as the dating of most of them is unknown, only the more significant examples are discussed.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 95) The crosses Harbison discusses are: The Market Cross, located in the Interpretative Centre; a cross near Reefert Church; a ringed granite cross near the Cathedral. These crosses will be presented first.

There are several additional crosses listed under the heading “Crosses: High Crosses” in the National Monument Service website. These will be considered next. Finally, a group of additional crosses classed by the National Monument Service as “Cross” will be considered.

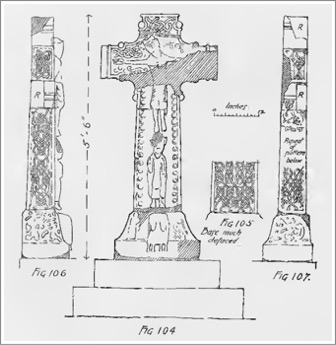

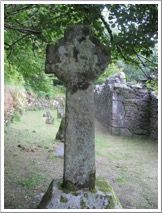

The Market Cross or Brockagh

The National Monument Survey names this cross as Brockagh. It is listed as WI023-077 in the survey.

While its original location is unknown it is known to have been in front of the Royal Hotel (now gone), inside St. Kevin’s church and in its present location.

The cross stands 5’6” (1.7m) in height and 2’6” (79cm) across the arms. It is carved of granite. The description below is based on Harbison’s assessment. (Harbison, 1992, p. 95)

East Face:

Base: Two figures, possibly holding books are at the center of the base, standing on a raised platform. There may be two additional figures to the left. The right side of the base is too deteriorated to identify any carving. See figure 104 below from Cochrane.

The Cross: The shaft is framed by roll moulding with pellets inside. The figure of a bishop or abbot, who may represent St. Kevin, stands below an image of the crucifixion. Jesus’ long, slender body is dressed in a loincloth. His head, which may be crowned, falls to the left.

The South Side: (Fig. 106 below)

Base: Any decoration is too worn to identify.

Cross: The shaft has animal interlace with a ribbon coiling around the animals. The end of the arm also has animal interlace.

West Face:

Base: There is interlace.

Cross: The shaft has irregular interlace with tendril endings. (See Fig. 105 above) The head has floral motifs flanked by raised mouldings.

North Side:

Base: The decoration is unclear. (See Fig. 107 above)

Cross: Animal interlace in figure-of-eight mouldings. Decoration on end of arm is unclear.

Reefert Cross, Lugduff

The painting to the right depicts a window on the south side of the Reefert Church. (See Art Gallery)

This cross is carved of mica schist and stands 7’2” (2.2m) in height. Here the description is based on the description offered in the National Monument Survey, which in turn is based on the work of Harbison and Leask. The NMS refers to this cross as Lugduff.

This cross is carved of mica schist and stands 7’2” (2.2m) in height. Here the description is based on the description offered in the National Monument Survey, which in turn is based on the work of Harbison and Leask. The NMS refers to this cross as Lugduff.

The west face of the head has “an elaborate circular pattern, consisting of a Greek cross formed of one continuous band and surrounded by two rings. The circular centre of this cross contains a design similar to the triskelion, but having two arms only, and the triangular ends contain triquetras. In the quarters are interlaced knots.” (National Monument Survey) (Center image below Cochrane, Fig. 77) The photo below left is the west face of the cross, that to the right is the east face.

Ringed Granite Cross, Sevenchurches or Camaderry

This cross stands nearly 11’ (3.35m) in height and a little over 3’6” (1m) across the arms. It stands to the south of the Cathedral and is carved of granite. It is otherwise undecorated. The NMS refers to this cross as Sevenchurches or Camaderry, WI023-008013.

The photo to the left shows the east face of the cross, that to the right the west face.

The Crosses: National Monument Viewer listing under High Crosses

These crosses include: Sevenchurches or Camaderry (WI023-008042); Sevenchurches or Camaderry (WI023-009019); Brockagh (WI023-028012); and Brockagh (WI023-028011).

Priest’s house, Sevenchurches or Camaderry

"Described by Leask (1950, fig. 19g, 42) as ‘a ringed cross of granite, unpierced, with a short shaft, probably broken. It stands at the west end of the “Priests house” but was possibly, like St. Kevin’s Cross, on the boundary of the ancient burial ground.’” (NMS)

Sevenchurches or Camaderry (WI023-009019)

“Described by Leask (1950, 45, 47) as the ‘head of a granite cross (3, Fig. 20) 3’3” (1m) wide and high is of the ring or wheel type with a solid recessed ring and small hollows at the intersection of shaft and arms. There are two small concentric circles at the centre and two incised lines form mouldings around the cross and emphasize its outline.’” (NMS)

Brockagh (WI023-028012)

“Described by Leask (1950, 40) as a ‘cross and base, 3’8” (1.1m) high. Head a complete, solid ring with short projecting arms, a circular band in shallow relief surrounding cross with curved, equal arms. The shaft is tapered with a slight entasis and is rebated shallowly at the edges.” This cross was described as having a base. The base seems to have been used for a replica that is outside the entrance to the Visitor Centre. (NMS)

Brockagh (WI023-028011) “Small portion of ringed head of cross ( 9.5” [0.24m], max width 14” [0.38m] and 2.5” [0.07m] thick). Outline of wheel discernible on faces (Leask 1950, fig. 18g. 40-1) The shaft and base still stand at Reefert church and have been designated no. WI023-028030. I have not located a photo of the head fragment, but the shaft and base that remain near the Reefert Church are pictured to the right. (NMS; illustration left Cochrane p. 77)

Roadside Cross: A Latin cross, 5’8” (1.7m) high, cut out of mica schist, and having one arm broken off. The only ornament consists of circular hollows at the angles of the intersection. It stands in a field between the road and the river near the bridge at the upper lake. this cross are in the line of the ancient “ Pilgrims’ Road,” now almost obliterated. (Cochrane, p. 75, illustration p. 77, Fig. 82)

Teampul-na-Skellig

Teampul-na-Skellig is in a remote location on the south side of the Upper Lake at the base of a steep incline. It is near the cave feature known as St. Kevin’s Bed. It was excavated by Francoise Henry. There is a small church on the site, pictured to the right, as well as “four sub rectangular house sites.” (Seaver, p. 20, and photo page 19)

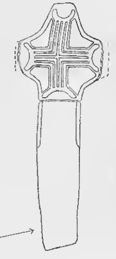

Fig, 71.—A rough Latin cross of mica schist, 3’ 9” (1.1m) high, decorated on the west side with an incised cross rising from a base consisting of four squares place done inside another, and having concentric circles at the centre and at the extremities of the arms. All the markings on crosses are symbolic. The circle has a spiritual significance while the square is worldly, and is frequently used to denote the connexion of the person commemorated with the particular locality of which he was possibly a native. (Cochrane, p. 76), (photo to the left https://historicgraves.com/temple-na-skellig/wi-tnsk-0005/grave)

Additional Crosses at Glendalough

In the National Monument Service Historic Environment Viewer the following crosses are listed under the heading “crosses” as opposed to “high crosses”. Dating for all these crosses must be considered undetermined.

Those Near Upper Lake

Class: Cross

Townland: LUGDUFF (Ballinacor South By. A)

Description: Set in a stone cairn some 60m NE of a possibly modern stone enclosure (WI023-025----). A large undecorated Latin cross of mica-schist with one arm broken away (H 1.4m; Wth 0.65m; T 0.17m). (Healy 1972, 222)

Townland: LUGDUFF (Ballinacor South By. B)

Description: Situated ENE of a possibly modern stone enclosure (WI023-025----) N of Reefert Church (WI023-028001-). A large undecorated Latin cross of mica-schist (H 1.1m; Wth 0.57m; T 0.1m) with one arm broken away; set into a stone cairn. Another triangular cross-base beside the above was missing in 1971. (Healy 1972, 22, 85)

Townland: LUGDUFF (Ballinacor South By. D)

Description: Set into a stone cairn SE of the possibly modern stone enclosure (WI023-025----) near Reefert Church. An undecorated irregular Latin cross of mica-schist (H 0.94m; Wth 0.54m; T 0.03m). (Healy 1972, 21)

Townland: LUGDUFF (Ballinacor North By. C)

Description: Erected on a stone base to W of centre of interior of church (WI023-027----) (Healy 1972, No. 220, 21, 82). Described by Healy (1972, 82) as a ‘small cross of mica-schist 0.88m x 0.53m x 0.04m thick. It is symmetrical in outline, and the shaft and arms are tapered’.

Townland: LUGDUFF (Ballinacor South By. E)

A rude cross of mica schist, 2 feet 7 inches high, having on the side a small plain cross in a rectangular frame, the upright stem being extended to the ground. I believe the cross in question is the one on the left in the photo to the left. (Cochrane p. 75, illustration p. 77 #76)

Townland: LUGDUFF (Ballinacor South By. F)

Description: Located: stands 7.3m NW of NW corner of nave of church (WI023-028001-) (Healy 1972, no. 207, 69). Described by Healy (1972, 66) as a ‘large plain Latin cross of mica schist 1.4m x 0.9m x 0.12m thick. The arms and head are partly broken away. It stands in a mortised base, also of mica schist 1.1m x 0.8m

Townland: LUGDUFF (Ballinacor South By. G)

Description: Located: 4.45m NE of NE corner of chancel of church (WI023-028001-) (Healy 1972, no. 217, 79). Described by Healy (1972, 79) as a ‘small rough cross of mica-schist 1.14m x 0.36m x 0.05m thick’.

The following group of crosses were described by Cochrane in 1911-12 and are also described, using Cochrane’s illustrations by Leask. I have had difficulty identifying the location of many of these crosses. As with the grouping above, dates for the carving of these crosses is undetermined.

Near Reefert Church

"A cross of mica schist, 3 feet 8 inches high, having a massive base and a head which shows the complete ring, and has in the centre a Greek cross formed of circular curves. (Cochrane p. 75, illustration left, fig. 78, p. 77)

Roadside Crosses

A cross of mica schist 2 feet 6 inches high, carved with a singular pattern consisting of grooves forming a saltire in the centre, and on the arms panels whose sides correspond in direction to the lines of the saltire. It is on a low mound in a field between the road and the lower lake. (Cochrane, p. 75, illustration p. 77, Fig. 81)

At St. Mary’s Church

A rough cross of mica slate 1 foot 9 inches high, the arms of which expand slightly towards the ends. It is fixed in a socket and stands 10 feet west of the church. (Cochrane, p. 76, illustration p. 77, Fig. 92)

St. Kevin’s Church Some of the crosses mentioned below are probably no longer inside St. Kevin’s Church. I hope on my next trip to Glendalough to locate as many of these as I can and add photographs and current location to the information below.

A ringed cross of mica slate (broken in two), 2 feet 10 inches by 12 inches by 1 inches thick. On the front is a circular band in relief carved with plain zigzag pattern, above which is an upright chevron. Round the edge is a small rebate and on the shaft a plain lattice of five compartments. On the back is a Greek form cross of bands, mitered together at the centre and finishing in crescent shaped ends. (Cochrane, p. 82, Fig. 111/ VIII p. 81)

The central portion of a large cross head of mica schist, 1 foot 9 inches by 1 foot 5 inches by 2 inches thick. In the centre is a small circle surrounded by a Greek cross placed diagonally, and shaped as a square with the angles hollowed out in curves. (Cochrane, p. 82, Fig. 112/ IX p. 81)

The central portion of a cross head of mica schist, 1 foot 9 inches by 1 foot 4 inches by 3 inches thick. It is plain, with the exception of curved lines which mark out the quadrants of the ring. (Cochrane, p. 82, Fig. 113/ X p. 81)

A cross of mica schist, 3 feet 1 inch by 1 foot , the ring is sohd and a plain cross with rounded angles is carved in slight relief The head is separated from the shaft. (Cochrane, p. 82, Fig. 114/ XI p. 81)

The head of a cross of mica schist, 1 foot 5 inches by 1 foot 2 inches. The ring is marked off from the cross proper by incised lines partly worn away. (Cochrane, p. 82, Fig. 115/ XII p. 81)

The head of a small cross of mica schist, 1 foot 2 inches by 10 inches by 2 inches thick. The lower segments of the ring are broken, and the intersection of the cross is above the centre of the ring. This is the only cross with a pierced ring now to be found at Glendalough. (Cochrane, p. 82, Fig. 116/ XIII p. 81)

The head of small cross of mica schist, 1 foot 2 inches by 1 foot 1 inch by l inch thick. The ring is not separated from the cross by any incision, and the arms are slightly tilted and are placed above the centre of the ring (Cochrane, p. 82, Fig. 117/ XIV, p. 81)

The central portion of a small rude cross of mica schist, 1 foot one half inches by one and three quarters thick ; a small Greek cross is incised on each face. One of these crosses has another smaller cross at the upper extremity. (Cochrane, p. 82, Fig. 118/ XV, p. 81)

The head of a rude ) cross, 1 foot 2 inches by 9 inches by one and one quarter inch thick formed by cutting four notches in a slab of mica schist. (Cochrane, p. 82, Fig. 119/ XVI, p. 81)

The head of a rude cross, 1 foot 2 inches by 9 inches by one and one quarter inch thick, formed by cutting four notches in a slab of mica schist, somewhat similar to No. XVI. (Fig. 120)(Cochrane, p. 82, Fig. 120/ XVII, p. 81)

The head of a rude cross, 1 foot 4 inches by 1 inches thick, formed as No. XVII., but having the upper end rounded, and incised with three short vertical lines. (Cochrane, p. 82, Fig. 121/ XVIII, p. 81)

The lower portion of a cross of mica schist, 1 foot 6 inches by 5 and one third inches by one and three quarters inches thick. This cross consisted of a tapering shaft supporting a head" formed by four limbs; which expand towards the ends. The upper and side limbs are missing. (Cochrane, p. 82, Fig. 122/ XIX, p. 81)

The head of a plain Latin cross of mica schist, 1 foot 3 and one half inches by 1 foot 2 inches by 2 inches thick, incised on one side with a plain double line cross now almost worn away. (Cochrane, p. 82, Fig. 123/ XX, p. 81)

The head of a plain Latin cross of mica schist, 10 and one half inches by 10 and one half- inches by 2 inches thick. (Cochrane, p. 82, Fig. 124/ XXI, p. 81)

XXII. The head of a small plain cross of mica schist, 1 foot 2 inches by 5 and one half- inches by I and three quarters inch thick. (Cochrane, p. 82, Fig. 125/ XXII, p. 81)

XXIII. The head of a small plain cross of mica schist, I foot 0 and one half inch by 6 and one half inches by 1 and one half inches thick, similar to No. XXII. (Cochrane, p. 82)

XXIV. The lower portion of a small cross of mica schist, one and one half inches by seven and one half inches by one and one half inches thick, similar to No. XXV. (Cochrane, p. 82)

XXV. The lower portion of a small cross of mica schist, 10 and one half inches by 7 and one half inches by 1 inch thick. (Cochrane, p. 82, Fig. 126/ XXVI, p. 81)

XXVI. A plain cross of mica schist, 2 feet by three inches by 9 and one half inches by 2 and one quarter inches thick. The limbs expand slightly towards the ends and the shaft tapers. Fig. 127. (Cochrane, p. 82, Fig. 127/ XXVI, p. 81)

XXVII. A plain cross resembling No. XXVI., two feet 6 inches by 10 inches by 2 inches thick. One arm is missing. (Found at the west end of St. Kevin’s church in 1912.) Fig. 128. (Cochrane, p. 82, Fig. 128/ XXVII, p. 81)

XXVIII. A carved fragment of uncertain allocations, 1 foot 4 inches by 8 inches by three and one half inches thick. It shows portion of a flat band in relief, 2 and one half inches wide, turned at right angles. Inside the angles of this band the stone forms a rebate, above the- band are the legs of a human figure, the remainder is broken away. Portions of interlaced and spiral designs appear at the side. (Fig. 129.)

Resources Consulted

Barrow, Lennox, “Glendalough and St. Kevin”, Dublin Historical Record, Vol. 27, No. 2, March, 1974, pp. 49-64.

Cochrane, Robert, “The Ecclesiastical Remains at Glendalough, Co. Wicklow,”, Public Works, Ireland, Eightieth Annual Report of the Commissioners of Public Works in Ireland, London, 1912. pp. 45-88.

Corlett, Christiaan, August 13, 2013, http://www.christiaancorlett.com/blog/4564514201/The-great-stone-font-at-Aghowle-Co.-Wicklow/6332783.

Corlett, Chris, The Abandoned Cross at Ballintubber, Hollywood, Co. Wicklow, Archaeology Ireland, vol. 25, No. 2 (Summer 2011), PP. 26-29, Photo page 28.

Corlett, Christiaan, "Two Recently Discovered Crosses from Co. Wicklow" The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland Vol. 135 (2005), pp. 140-144

County Wicklow Heritage: http://countywicklowheritage.org/page_id__16_img__187.aspx

County Wicklow in Prehistory: http://www.heritageinschools.ie/content/resources/Wicklow%20in%20Prehistory/Wicklow_in_Prehistory.pdf

Crawford, Henry S. “Descriptive List of the Early Irish Crosses”. The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol, 37, (June. 30, 1907) pp. 187-239.

Culleton, Edward, "Celtic and Early Christian Wexford," Four Courts Press, Dublin, 1999.

Find a Grave: https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/2597311/kilquiggan-graveyard

Harbison, Peter, 1992, The High Crosses of Ireland: an Iconographical and Photographic Survey, 3 vols. Dublin. Royal Irish Academy. Bonn. Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH.

Healy, P. 1972, “Supplementary Survey of Ancient Monuments at Glendalough, Co. Wicklow”. Unpublished OPW report.

Historic Environment Viewer: https://maps.archaeology.ie/HistoricEnvironment/

Hughes, Kathleen, “The Church in Irish Society, 400-800, in O Croinin, Daibhi, ed.; "A New History of Ireland: Prehistoric and Early Ireland", Oxford University Press, 2005.

Leask, H. G., 1950, Glendalough, Co. Wicklow: National Monuments Vested in the Commissioners of Public Works, Dublin. Stationery Office.

List of Monastic Houses in County Wicklow: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_monastic_houses_in_County_Wicklow

Lobell, Jarrett A., “Medieval Cattle Raiders”, Archaeology Magazine, March/April 2020. https://www.archaeology.org/issues/376-2003/sidebars/8452-ireland-national-epic

Mason, Johathan, "An Early Christian cross base in Bray" Archaeology Ireland Vol. 24, No. 3 (Autumn 2010), pp. 26-29

O’Corrain, Donnchadh, “Ireland c. 800: Aspects of Society” in O Croinin, Daibhi, ed.; "A New History of Ireland: Prehistoric and Early Ireland", Oxford University Press, 2005.

Raftery, Barry, “Iron Age Ireland” in O Croinin, Daibhi, ed.; "A New History of Ireland: Prehistoric and Early Ireland", Oxford University Press, 2005.

Rathgall Hillfort and Aghowle Church, Rath, Coolkenno, Co. Wicklow, brochure, http://www.countywicklowheritage.org/documents/Rathgall_and_Aghowle_Brochure_2008_2009.pdf.

Seaver, Matt, Conor McDermott and Graeme Warren "A MONASTERY AMONG THE GLENS”, Archaeology Ireland , Vol. 32, No. 2 (Summer 2018), pp. 19-23

Stout, Geraldine, “The Archaeology of County Wicklow,” Archaeology Ireland, Winter, 1989, Vol. 3, No 4, pp. 126-131.

Visit Wicklow: https://visitwicklow.ie/item/pipers-stones/

Walsh, Thomas, History of the Irish Hierarchy, with the Monasteries of Each County, D. & J. Sadlier & Co., New York, 1854.

Wicklow archaeological objects, http://rmchapple.blogspot.com/2019/05/co-wicklow-archaeological-objects-at.html

Wicklow Heritage: https://heritage.wicklowheritage.org/places/river_liffey_heritage_project-2/burgag e_more