This page describes the crosses in County Sligo. They include a cross, cross-shaft and fragments from Drumcliff; a cross-head at Drumcolumb and a base at Templehouse Demesne. The location of County Sligo is indicated by the red star on the map to the right.

Historic Background

The modern County of Sligo has been part of the province of Connacht from antiquity. There is significant evidence that this province was occupied far back into prehistory.

The name of Connacht derives from the most successful early dynasty in the area, the Connachta. The Connachta were a group of dynasties that all claimed descent from Conn Cetchatharc, “Conn of the Hundred Battles”, a legendary Irish king. (Charles-Edwards p. 36) These dynasties seems to have expanded outward from Cruachain, the traditional capital of Connaught in the present County Roscommon. By 1050 various dynasts of the Connachta controlled Sligo, Roscommon, Galway, Mayo and Leitrim.

The Mesolithic and Neolithic Ages (4500 to 2500 BCE)

A causewayed enclosure, discovered in 2003 at Maugheraboy, is one of the earliest indications of Neolithic farming activity on the Cúil Irra peninsula west of Sligo. This enclosure dates to about 4000 BCE. Maugheraboy is close to one of two major neolithic cemeteries in County Sligo, Carrowmore. Carrowmore neolithic cemetery is located on the Cúil Irra peninsula. The tombs here were built in the 4th millennium BCE. The earliest tomb dates to around 3700 BCE. A second neolithic cemetery, Carrowkeel, is located in southern Co. Sligo and also dates from the 4th millennium BCE.

The Bronze Age (2500 to 500 BCE)

Metal work in bronze gives this period of history its name. Archaeological features include megalithic tombs for burials that change gradually to wedge tomb and cist burials. In 2014 part of fulacht fiadh, a stone lined box that is usually associated with cooking, was discovered on Coney Island, just north of the Carrowmore neolithic cemetery. The stone lined pit would be filled with water and heated with hot stones. (Bronze Age Fulacht fiadh)

The Iron Age (500 BCE to 400 CE)

The introduction of Iron work seems to have coincided with the arrival of the Celtic people and their language about 500 BCE. Archaeological features include crannogs, promontory forts, ring forts and souterrains. For example there is a promontory fort at Knoxspark just south of Ballysadare that has an enclosing fosse and internal bank. (Knoxpark) It was also during this time that the Ogham alphabet appears and that the tales of the Ulster Cycle are supposed to have taken place.

The Early Christian Period (400 to 1000 CE)

According to Ptolemy’s second century map, the area of modern Sligo was inhabited by the Nagnate and Erdin. These were names given by Ptolemy and don’t reflect what the people called themselves. Across the centuries, beginning in the early Christian era, there were several tribal groups of the Connachta that dominated all or part of what is now County Sligo. “Ireland’s History in Maps” suggests that from 500 through at least 950, the Luigne were active in Sligo. The Clarraige appear in the maps for 500, 800, and 950. A tribal group know as the Ui Ailella appear on the map for 700 and on the map for 1000 the Ui Briuin Breifne appear. (Rootsweb 1)

The Luigne were a tribal group mentioned in the annals, hagiography and genealogies. One branch settled in County Sligo. (Gleeson) The Ui Briuin were descended from Brion, the sone of Eochu Mugmedon, a fourth century ‘high king’ of Ireland. The Ui Briuin, along with the Ui Fiachrach ruled the province of Connacht for seven centuries. (Rootsweb 2) The Ui Briuin Breifne were one branch of the Ui Briuin. They became the leading force in Connacht in the 7th and 8th centuries. By the 10th century a Kingdom of Breifne developed that encompassed the present counties of Leitrim and Cavan, just to the northeast of present day Sligo.

While we have names of numerous tribal groups in Connacht, as noted above, Daibhi O Croinin comments that sources for the history of Connacht before about 800 are almost non-existent. (O Croinin, p. 227) This includes the tribes mentioned above; the Luigne, the Clarraige, the Ui Ailella and the Ui Briuin. He also notes that “alone among the provinces, Connacht lacks any strong tradition of an over-kingship.” (O Croinin, p. 227)

Ecclesiastical History

Below is a listing of the early church/monastic sites in County Sligo. Eight of these monasteries are attributed to the work of St. Patrick, who was active in the 5th century. Four, founded in the 6th century, are attributed to St. Colmcille. Another four, founded in the 7th century, are attributed to St. Fechin of Fore.

It is no surprise that St. Patrick, one of the three patron saints of Ireland, was active in this area. His founding of churches/monasteries across large parts of Ireland is well known. St. Colmcille, another of the patron saints of Ireland, was born into the Cenel Conaill, a branch of the Northern Ui Neill. He is remembered as founding the monastery at Derry, other monasteries in Ireland and Iona and additional monasteries in Scotland. St. Fechin was born in what is now County Sligo. He is best known for founding the monastery at Fore in what is now County Westmeath. Fechin was associated with the Luigne of Connacht, referred to above.

Information for the following list of early monasteries in what is now County Sligo can be found in the resource listed as Monastic Houses in County Sligo. (Monastic Houses in County Sligo)

Achonry Monastery, early site, founded 7th century by St. Finnian of Clonard

Aghanagh Monastery, early site, founded 5th century by St. Patrick

Alternan Monastery, early site, founded 6th century by St. Colmcille or St. Farranan

Aughris Priory, early site, founded by St. Molaise of Inishmurray

Ballysadare Abbey, early site, founded 7th century by St. Fechin of Fore

Billa Monastery, early site, founded 7th century by St. Fechin of Fore

Caille-au-inde, early site, founded by St. Fintan, son of Aid

Carricknahorna, early site, nuns, founded 5th century by St. Patrick

Church Island, Lough Gill, early site, founded 6th century by St. Loman

Cloonoghill Abbey, early site, founded 6th century by Aedan O Flachrach

Dromard Monastery, early site, nuns, founded 5th century (?) by St. Patrick

Druimlias Monastery, early site

Druimeidirdhaloch, early site, founded by St. Finnian of Clonard

Druimnea Monastery, early site, founded 5th century by St. Patrick

Drumcliff Monastery, early site, founded 575 by St. Colmcille

Drumcolumb Monastery, early site, founded 6th century by St. Colmcille

Drumrat Monastery, early site, founded 7th century by St. Fechin of Fore

Emlaghfad Monastery, early site, founded 6th century by St. Colmcille

Enachard Monastery, early site, nuns

Faebhran Monastery, possible site

Inishmurray Monastery, early site, founded 5th century by St. Laisren (Molaise)

Keelty Monastery, early site, nuns, founded by St; Muadnata ?

Kilcumin Monastery, early site, founded by St. Caeman or St. Comegen ?

Killaraght Monastery, early site, nuns, founded 5th century by St. Patrick

Killaspugbrone early site

Killerry Monastery, early site, founded 5th century, in time of St. Patrick?

Kilmacowen Monastery, early site, founded pre mid 6th century by Diermit

Kilnemanagh Monastery, early site, founded 7th century by St. Fechin of Fore

Kilross Monastery, early site

Monasteraden Monastery, early site, founded by St. Aedha

Monaster-Cheathramh-nTeampuill, early site

Shancough Monastery, early site, founded 5th century by St. Patrick?

Screen Monastery, early site, founded 6th century by St. Colmcille

Staad Abbey, early site, founded by St. Molaise of Inishmurray

Tawnagh Monastery, early site, founded 5th century by St. Patrick

Toomour Monastery, early site

Crosses and cross fragments are known from only three of these numerous monasteries. There is a cross, a cross shaft and additional cross fragments at Drumcliff. There is a cross-head at Drumcolumb and a cross base at Templehouse Demesne. This latter site cannot be identified with any of the monasteries listed above. Below each site is introduced, the crosses and cross fragments are described and pictured.

Drumcliff Crosses

The Monastery

Druim Cliabh (Drumcliff) was known to Irish legend prior to the establishment of a monastery there. The name translates to “the Ridge of [boat] frames” and derives from the construction there of about 150 boat frames used by Curnan the Backlegged to attack and destroy Dun Barc, possibly located in Bantry Bay. (Stokes p. 551)

The photo to the right shows the sandstone cross with the remains of the round tower in the background.

The Martyrology of Donegal tells us that St. Columba founded the monastery at Drumcliff about 575. He left Mo-Toren (Mothairen) there as the first abbot. (Stokes p. 552) The founding of the monastery took place after Columba had left Ireland for exile on Iona in Scotland. It happened when he was back in Ireland for a time to attend the synod at Drumkeatt. Following that synod he visited numerous churches and monasteries and founded monasteries, including Drumcliff. (Stokes p. 553)

Stokes reports that it was not until the 9th century that Drumcliff gained notice in the Irish annals. She mentions the following entries.

M921.3 Maelpadraig, son of Morann, Abbot of Druim-cliabh and Ard-sratha;

M930.6 Maenghal, son of Becan, Abbot of Druim-chliabh;

M950.4 Flann Ua Becain, airchinneach of Druim-cliabh, scribe of Ireland, died.

M1029.5 Aedh Ua Ruairc, lord of Dartraighe; and the lord of Cairbre; and Aenghus Ua hAenghusa, airchinneach of Druim-cliabh; and three score persons along with them, were burned in Inis-na-lainne in Cairbre-mor.

M1053.4 and Murchadh Ua Beollain, airchinneach of Druim-cliabh, died.

M1187.8 Drumcliff was plundered by the son of Melaghlin O'Rourke, Lord of Hy-Briuin and Conmaicne, and by the son of Cathal O'Rourke, accompanied by the English of Meath. But God and St. Columbkille wrought a remarkable miracle in this instance; for the son of Melaghlin O'Rourke was killed in Conmaicne a fortnight afterwards, and the eyes of the son of Cathal O'Rourke were put out by O'Muldory (Flaherty) in revenge of Columbkille. One hundred and twenty of the son of Melaghlin's retainers were also killed throughout Conmaicne and Carbury of Drumcliff, through the miracles of God and St. Columbkille.

M1225.1 Auliffe O'Beollan (Boland) Erenagh of Drumcliff, a wise and learned man and a general Biatagh, died.

M1252.1 Maelmaedhóg O'Beollain, Coarb of Columbkille, at Drumcliff, a man of great esteem and wealth, the most illustrious for hospitality, and the most honoured and venerated by the English and Irish in his time, died.

M1267.5 A depredation was committed by the English of West Connaught in Carbury of Drumcliff, and they plundered Easdara Ballysadare.

(Annals of the Four Masters)

The Crosses

Sandstone Cross: This is the only complete cross at Drumcliff. It stands 9’10” (3m) in height and measures about 3’7” (1.1m) across the arms. The shaft measures 18.5” (47cm) by 12” (31cm). The stepped base on which it stands is nearly 33.5” (83cm) in height. At ground level is measures 48” (1.23m) by 38.5” (98cm). Harbison points out that the head does not seem to have been that originally planned for the shaft. He suggests that it is a replacement that was either carved at the time due to a change of plans or somewhat later to replace the original head. (Harbison, 1992, p. 70)

The cross is not divided into separate panels, however the divisions between the images is generally very clear. The descriptions below depend on the work of Harbison (1992 pp. 70-73) and Stokes (pp. 551-556). Where their descriptions diverge , that fact will be indicated.

East Face: See the photo to the right.

E 1: There is an interlace pattern composed of four circles that Stokes describes as the roots of the Tree of Knowledge.

E 2: The Fall of Man. In this image Eve, on the left, appears to eat the apple. At the same time both Eve and Adam hide their nakedness.

E 3: An animal in high relief that seems to be a lion.

E 4: Harbison identifies this scene as David Slaying Goliath while Stokes identified it as Cain killing Abel. Harbison notes details such as Goliath holding a shield in support of his identification. His argument is persuasive. (Harbison, 1992, p. 71)

E 5: Daniel in the Lion’s Den

Center of Head: Stokes identified the figure here as a bishop, perhaps St. Columba. Harbison sees this as a depiction of either the Second Coming of Christ or the Last Judgment. The key identifier is the cross held over the right shoulder of the figure. If this were a bishop a crozier would be expected instead.

Arms: Each of the arms has five heads. The upper part of the shaft is broken but may contain six heads. Stokes identifies these as cherub heads. Harbison does not attempt an identification.

South Side: See the photo to the left.

S 1: Bottom panel that is undecorated.

S 2: Various interlocking spirals.

S 3: blank panel with a mortise hole.

S 4: Two interlaced animals with interlacing ribbon.

S 5: Top panel of shaft is undecorated.

S 6: An animal seems to crouch. Harbison describes this as a lion while Stokes identified it as a stag.

Underside of Ring: Harbison describes an animal seen from above and facing down toward the shaft. Stokes identifies this as a seal and frog.

End of Arm: Virgin and Child

West Face: See the photo to the right.

W 1: Interlaced design.

W 2: Harbison identifies this scene as the naming of John the Baptist or the presentation of John in the temple. Stokes sees it as the presentation of Jesus in the temple.

W 3: An animal figure that Harbison identifies as a camel and Stokes suggests might be an Irish wolf dog.

W 4: The smiting of Jesus. Harbison specifies the second mocking.

W 5: Harbison suggests this may be the return of Mary and Joseph from Egypt or less likely Zacharias and Elisabeth bring John the Baptist for circumcision. Stokes guesses that the figures could be Mary and John.

Center of Head: Crucifixion with lance and sponge.

Arms: On each arm is a head. Stokes identifies them as cherub heads while Harbison suggests they may represent the thieves crucified with Jesus.

Top: Circular interlace.

North Side: See the photo to the left.

N 1: Blank panel.

N 2: Interlace

N 3: Blank panel with tortoise hole.

N 4: Fretwork with spirals and interlace.

N 5: Stokes identifies this as a lion in high relief.

Under the ring: An animal in high relief similar to that on the south side.

End of Arm: There is another animal similar to that on the underside of the ring.

Undecorated Shaft

This undecorated cross shaft stands nearly 10 feet in height and stands on a base that is nearly 4 feet in height. A mortise hole in the top is there to receive a missing head. See the photo to the right. This shaft is referred to as the Angel Stone.

Fragments in the Church walls

One of the chaplains at the Drumcliff church, Father Malcolm, point out that there are two decorated stones that have been built into the walls of the church that have been identified as fragments of one or two high crosses. The first fragment is in the main body of the church just to the right as you enter the sanctuary. It is a very large stone as shown in the photo to the left.

The second fragment is in the wall behind the lefthand door to the sanctuary as you enter, as shown in the photo to the right.

Fragments in the National Museum

DU018-181—- The shaft of the high cross the base of which stands in the graveyard at Drumcliff, Co. Sligo (SL008-084008) There are two sections of the cross-shaft, joined by a modern concrete filler. Only one face of the cross is visible as it is displayed standing against a wall. See the photo to the left.

The lower fragment measures 22.5 inches high (60 cm), 14.5 inches across (34 cm), and 9 inches thick (22.5 cm).

East Face: See the photo to the left. At the bottom of the shaft is a narrow plinth with an empty panel. It is set off by double roll-moulding. Above this there is a pattern of interlace that has four circular motifs that are interconnected. In the center there is a cruciform pattern crossed by strands of the interlace that connect the panels diagonally.

The panel at the top of this fragment is broken, making identification of the image there difficult. Harbison identified the image as David Slaying the Lion. He wrote: “The animal’s body and feet are visible, one of the front legs being raised. David’s right knee is visible on the lion’s back, while the lower part of the left foot can be seen beneath the front part of the lion’s body.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 73)

The Sides: On the right or north side there is a plinth and two panels, both undecorated. The panels have double roll-moulding. See the photo to the left. The left or south side has a plinth. Above this is a semi-circle then an undecorated panel with concave ends. Above this is a circle and the lower end of another apparently concave panel. See the photo to the right. (Harbison, 1992, p. 73 and Vol. 2, Fig. 223)

West Face: There is no clearly defined plinth. The lower panel has an interlace design similar to that on the east face. The panel above is broken. In the panel are the lower torsos of three figures, each clothed in a long robe. While a number of possibilities exist for explaining the meaning, there is not enough of the panel to provide any context. See the photo to the left. (Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 224)

The upper fragment measures 32 inches in height (83 cm) and tapers to 10.25 inches near the top (30 cm in the middle of the fragment). It is 6.5 inches (16.5 cm) thick. There are two panels on the shaft with part of another panel forming the lower part of the head of the cross. There is an indication on the right side at the top of the shaft that there was probably a ring on the cross.

East Face: See the photo to the right. The lower panel represents Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac. There are two persons depicted. The left hand person is as tall as the panel and holds a club or some other weapon in his right hand. The right hand figure is smaller and appears to lean forward toward the left hand figure. He may be depositing a bundle of faggots on the altar. Above to the right, appearing to be on the back of the right hand figure is a sheep or ram. In the extreme upper right corner is a circle or boss that may represent the angel.

The upper panel contains an image of Daniel in the Lion’s Den. Daniel stands in the center of the panel with arms outstretched. On each side of Daniel there is a lion below and above his arms.

In the constriction of the arms there is the lower part of a figure that appears to be clothed to the knees. There is not enough context to hazard a guess as to the identity of this image.

The Sides: The South side has two panels too worn to identify any patterns. The North side appears to have two undecorated panels.

West Face: See the photo to the left. (Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 228) There are two panels on the shaft with another in the constriction of the arms. Harbison identifies the lower panel as an image of the Resurrection. Christ in the center is flanked by angels, one of which holds a staff of some sort. Below, on both sides of Christ’s feet there is a sleeping soldier with his weapon on his shoulder.

The upper panel has been identified as a Mocking of Jesus scene. Jesus, the central figure is flanked on each side by a figure taken to be a soldier. Each holds a stick or baton up to Jesus’ face.

In the constriction of the arms there is a knot of interlace. A pair of feet are above this but there is no context to venture a guess as to the identification.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 15 D 2. Located 7 miles north of Sligo along the N 15. The Angel Stone (cross-shaft) is located in the northwest corner of the cemetery, built into the wall. The main cross is on the north edge of the graveyard. The location of the two fragments is described above. They are in the church.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

"Annals of the Four Masters", CELT, Corpus of Electronic Texts, http://www.ucc.ie/celt/publishd.html,

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Stokes, Margaret and Westropp T. J., “Notes on the High Crosses of Moone, Drumcliff, Termonfechin and Killamery”, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Vol. 31 (1896/1901), pp. 541-578.

Drumcolumb Cross-head

In the early Christian period Drumcolumb was known as Druim-namac. Tradition states that the church was established by St. Columba. He left his disciple Finbarr in charge of the foundation. (O’Hanlon, p. 554)

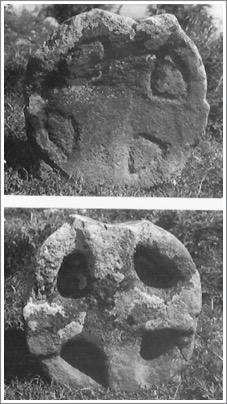

The cross-head lies on a hill-top. It is about 18.” (47cm) by 17” (44cm). It is about 3.5” (9cm) thick. The cross-head may not have been finished. It is imperforate but on one side the process for perforation is advanced while on the other the outline has been pecked out. The ring is not quite circular and on one side the arm extends just beyond the ring while on the other it comes only to the outside of the ring. (Harbison, 1992, p. 74, photos Vol. 2, Fig. 230 a and b)

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 16 E 4/5. Located east of Riverstown along an unnamed road that moves east then southeast. The site is off the road to the north. I was unable to reach the top of the ridge where the cross and some minor ruins are said to be due to the wet conditions. Finding this cross-head several fields off the road proved to be more than I could accomplish.

Sources Consulted

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

O’Hanlon, John, Lives of the Irish Saints: With Special Festivals, Volume 6, 1873.

Reeves, William, ed., The Life of Saint Columba: Founder of Hy, Volume 6.

Templehouse Demesne Cross-base

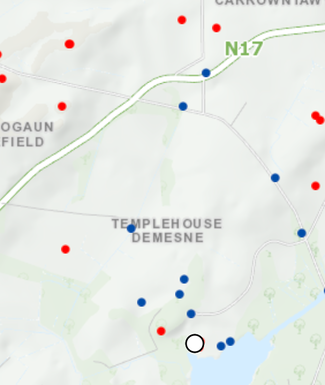

There is a cross-base situated on the line of the missing west wall of a Knights Templar castle. It is made of limestone. The base is nearly 16” (40cm) in height. At ground level it measures about 27” (68.5cm) by 24” (61cm). There is a mortise hole in the top. The base does not appear to have any decoration. Harbison lists this as a base that is possibly pre 1200. (Harbison, 1992, p. 393)

“Temple House, a luxury Country House in county Sligo, Ireland, is a classical Georgian manor set in a private estate of over 1,000 acres, overlooking a 13th century lakeside castle of the Knights Templar. The Perceval family home since 1665, the present manor was redesigned in 1864 and enjoys the authentic and unpretentious luxury country house atmosphere.” (https://www.templehouse.ie) The photo to the left shows the ruins of the Knights Templar castle.

In the photo to the left below you can just make out the cross-base in its setting, on the right side of the right section of ruin in the picture to the right.

Just below is a photo of the base itself.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 15 D 5. Located southeast of the N 17 near the shore of Templehouse Lake. From the N17 take the road marked Templehouse Lake Road. At the entrance to Temple House go through the gates. To your left as you approach the main house you will see ruins to your left, near the lake. The cross-base is located as indicated above.

Sources Consulted

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Historic Environment Viewer: http://webgis.archaeology.ie/historicenvironment/

Home Thoughts from Abroad:

https://homethoughtsfromabroad626.wordpress.com/2014/09/17/temple-house-sligo-ireland/