This page presents the High Crosses of County Kilkenny. The crosses described are Dunnamaggan, Graiguenamanagh, Kilkieran, Killamery, Kilree, Leggetsrath, Thomastown, Tybroughney, and Ullard. Two of these crosses, Dunnamaggan and Thomastown, are not listed by Peter Harbison but appear in the listing of crosses compiled by Henry Crawford. They are almost certainly 13th century, and thus outside the usual terminal date of 1200 for Irish High Crosses established by Peter Harbison. The paper begins with a survey of Kilkenny History, both secular and ecclesiastical, up to about 1200. The location of County Kilkenny is indicated by the red star on the map to the right.

Historical Background on County Kilkenny

The Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age

By as early as 4500 BCE the area of modern County Kilkenny was occupied by an agricultural people who domesticated both plants and animals. The Bronze Age began in this area about 2500 BCE, followed about 2 millennium later by the Iron Age. The Iron Age began between 600 and 500 BCE. About 250 BCE the Laigin from Armorica in northwestern France appear to have arrived in southeast Ireland. (https://sites.rootsweb.com/~irlkik/timeline.htm)

The following summary of the secular history of County Kilkenny is based largely on a History of Ossory found in https://sites.rootsweb.com/~irlkik/history/ossory.htm

First and Second Centuries

About 100 CE a group of Munster people, the Osraighe, formed a semi-independent state in the west of Leinster in what is now County Kilkenny.

Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Centuries

About 460 the Deisi conquered the south of Ossory and ruled it for more than a century. This area was largely recovered by about 630. During the 7th century Osraighe was allied with Munster. As a result they were rivals of the Laigin (Leinster).

Ninth Century

The Vikings first raided Ossory in about 823. Their raid was on St. Mullins, on the river Barrow. In 845, Cearbhall macDunlainge was lord of Ossory. That year he defeated the Vikings of Dublin. In the following years there were times when Ossory worked with the Vikings against Leinster and other neighbors to the north. In 846 Cearbhall, with help from the Vikings, defeated the Leinstermen. This alliance recurred in 856 when Cerball and the Norsemen defeated the Cinel Fiachach, an Ossory neighbor to the north. This was followed up with a defeat of Leinster. In 871, Cearbhall joined forces with the Eoghanacht of Munster in a raid on Connacht. Cearbhall died in 888.

Tenth and Eleventh Centuries

The tenth century was a difficult one for Ossory. In about 939, Muircheartach, son of Niall, plundered the areas of Osraighe and Deisi. Later, in about 981, Brian Boru plundered Osraighe and by 984 Brian gained control of all of southern Ireland. For a short time in the 1030’s Donnchadh macGilla Patraic macDonnchada, a descendent of Cearbhall, became king of Leinster.

Ecclesiastic History

Christianity reached the southeast of Ireland as early as 350, about a century before the ministry of St. Patrick. It is believed that St. Kieran (Saighir) founded a diocese or see in Ossory around 402. It is recorded that in c. 450 St. Patrick visited Ossory and established a church near the present city of Kilkenny. ( https://sites.rootsweb.com/~irlkik/timeline.htm)

The Timeline referenced above lists the following dates related to the history of Christianity in County Kilkenny. Note that it offers dates for the erection of a number of High Crosses.

“c530 - St. Ciaran of Seir founds a monastery at Grangefertagh.

c580 - St. Canice founds a monastery at Aghaboe.

c800 - Ossory Crosses of Kilkieran and Ahenny.

c820 - Celtic Crosses of Kilree and Killamery.

c860 - Celtic Crosses (granite) of Ullard, Graiguenamanagh, Castledermot, Newtown and St. Mullins.

1052 - The seat of the diocese of Ossory is moved from Sier-Kieran to Aghaboe. Some historians place this date as 1118.

1118 - At the synod of Rathbreasail the limits of the diocese of Ossory are permanently fixed. About the same time the see was transferred from Seir-Kieran to Aghaboe.

c1178 - The "See of Ossory" is moved from Aghaboe to the city of Kilkenny by the newly consecrated bishop of Ossory, Felix O'Dullany (1178-1202). He lays the foundation of the cathedral church of St. Canice. For some historians this happened after O'Dullany died in 1202.”

Several of the monasteries noted above are not located in the present County Kilkenny, though they were part of Ossory. These include Aghaboe which is in County Laois, Ahenny which is in County Tipperary, Castledermot and Newtown in County Kildare and St. Mullins in County Carlow.

During the early Christian period in Ireland, up to about 1200, there were numerous monasteries founded in what is now County Kilkenny. Below is a list of these early foundations as reported by the List of Monastic Houses in County Kilkenny. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_monastic_houses_in_County_Kilkenny The list omits the Monastery at Grangefertagh mentioned in the Rootsweb timeline above. It was founded in the 6th century by Saint Ciaran of Saigir.

Aghaviller Monasteryearly monastic, patronized by St. Brendan of Birr

Clonamery Monasteryearly site

Clonfert Kerpan Abbeyearly site, founded 503

Clonmore Monasteryearly site, granted to St. Mochoemoc

Columbkille Monasteryearly site, founded 6th century by St. Colmcille

Ennisnag Monasgeryearly site, founded 6th century by Manchan

Fetagh Prioryearly site, founded 5th century by St. Ciaran of Kierkeiran

Fiddown Monasteryearly site, founded 6th century

Freshford Monasteryearly site, founded 655-7 by St. Lachtain mac Torben

Inistoge Abbeyearly site, -possibly 6th century, by St. Colmcille?

Kells Prioryearly site, founded by St. Ciaran of Sierkieran

Kilcolumb Monasteryearly site, founded 6th century, by St. Colmcille

Kilfane Monasteryearly site, possibly founded by St. Phian

Kilferagh Monasteryearly site, possibly founded by St. Flachrius

Kilkenny Cathedral Monastery early site, founded before 599/600 by St. Canice

Kilkieran Monasteryearly site

Killaloe Monasteryearly site, founded c. 540 by St. Mocha

Killamery Monasteryearly site, founded c. 632 by St. Gobhan

Kilmanagh Monasteryearly site, founded before 563 by St. Natalis

Kilree Monasteryearly site, supposed to be founded by St. Brigid

Tibberaghny Monasteryearly site, founded 6th century, patronized by St. Mo-Dhomnog of Lann Beachaire

Tiscoffin Monasteryearly site, founded 6th century by St. Scuithin

Tullaherin Monasteryearly site, supposed to be founded by St. Cainnech

Tullamaine Monasteryearly site

Ullard Monasteryearly site, founded prior to 670 by St. Fiachra

Dunnamaggan Cross

This cross is not listed by Harbison as it was probably carved in the 13th century and may, as indicated below have a closer relationship to similar crosses in Cornwall than the traditional Irish High Crosses. It is included here because it is included in Henry Crawford’s list of crosses and because of its similarity to the cross at Thomastown (see the entry below) and its possible proximity in time to the production of the late Irish High Crosses.

The ruins of the church at Dunnamaggan are just a few miles south of the Kells Priory. Carrigan thought that the church, which has both Celtic and Gothic elements might date to the late 12th or early 13th century. (Carrigan p. 35) If this is the case, it is possible that the cross was carved near this same time. Its shape suggests a possible relationship with the Thomastown cross described below. Rynne has suggested a Cornish connection and a 13th century date for the Thomastown cross that might apply to the Dunnamaggan cross as well. (Rynne p. 20)

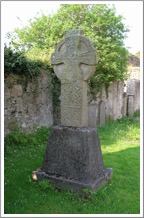

The cross stands in the graveyard. In 1839 it was broken with the shaft remaining in the base and fragments of the head on the ground nearby. It was repaired in 1852. (Carrigan, p. 36) The cross is carved of freestone, a rock that is typically of fine-grained sandstone or limestone and can be cut easily in any direction. The cross stands 5’ 4” (1.6m) high and measures 2’ 8” (0.8m) across the circle. The cross is 8” (20cm) thick. The base has one step and stands 1’ 9” (53cm) high and is 3’ 4” x 30" (1m x 76cm) at ground level. (Carrigan p. 35)

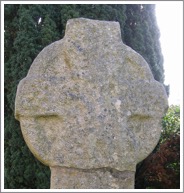

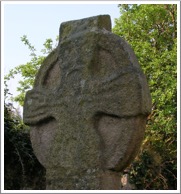

The arms do not project beyond the circle of the head but the top extends a few inches above and is quite small compared with the shaft. The most unusual feature of the head is that while the ring is perforated, the holes on the upper portion of the ring are square and those on the lower portion of the ring are round.

West Face: In the center of the head on the west is a crucifixion scene. See the photo to the right. On the shaft there is a sunken panel with a carving about 2’ (61cm) high that represents a bishop or abbot holding a crozier in the left hand and offering a blessing with the right hand. This has often been identified with Saint Leonard.

Saint Leonard was a Frankish noble in the court of Clovis I, the founder of the Merovingian dynasty. He became a Christian in 496 and worked for the release of prisoners of war. He was successful in securing the freedom of many such men. Leonard’s cult grew in popularity in the 12th century and spread throughout Western Europe. In England no fewer than 177 churches were dedicated to him. (http://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=300, 2/2017) He seems to be the patron saint of Dunnamaggan. He died in 559. (Carrigan p. 38)

East Face: In the center of the head on the east is a boss. See the photo to the right. On the Shaft there is a female figure in a sunken panel like that on the west face. It is thought that this figure may represent St. Catherine. (Carrigan p. 37)

The Saint Catherine referred to here was probably Saint Catherine of Alexandria. She was born in 287 and died in 305 at the age of about 18. She was martyred by the Emperor Maximizes who had her beheaded after her ardent defense of the Christian faith. (http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03445a.htm, 2017) Her cult grew and flourished following the report around 800 that her body has been rediscovered at mount Sinai, “with hair still growing and a constant stream of healing oil issuing from her body.”(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catherine_of_Alexandria#Medieval_cult, 2017)

Sides: Each side of the shaft contains a human figure smaller than those on the two faces. These figures cannot be readily identified. (Carrigan p. 37)

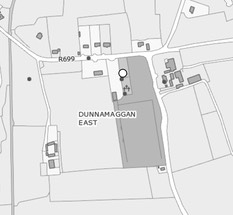

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 52 3 G. Just where the R699 turns from north to west on the east side of Dunnamaggan, the cross is located in an old cemetery next to the GAA sports facility See the map to the right.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Carrigan, William, “The History and antiquities of the Diocese of Ossory”, Vol. IV, Dublin, 1905.

Rynne Etienne, “The Thomastown High Cross — A Cornish Connection”, Kilkenny: Studies in honour of Margaret M. Phelan, John Kiran, Ed., Kilkenny Archaeological Society, 1997.

Saint Catherine of Alexandria: (http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03445a.htm, 2017)

Saint Catherine of Alexandria: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catherine_of_Alexandria#Medieval_cult, 2017)

Saint Leonard: (http://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=300, 2/2017)

Visions of the Past: https://visionsofthepastblog.com/2014/06/26/dunnamaggan-church-co-kilkenny/, 2/2017.

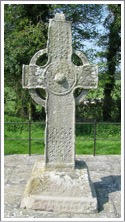

Graiguenamanagh Crosses

There are two crosses located on the grounds of the Duiske Abbey in Graiguenamanagh, now a local parish church. One of the crosses came from Aghakiltawn (aka Aghailta) and the other from Ballyogan, two outlying parishes. (http://www.ballyoganhouse.com/graiguenamanagh.php) The crosses were moved to the Duiske Abbey in about 1820.

The Crosses

Aghailta or South Cross

The description below is based on the work of Harbison. (Harbison, 1992, p. 97)

The South Cross stands on a modern base. It stands 5 feet 6 inches tall and is 36 inches across the arms. The head has an imperforate ring. There is roll moulding on the edges of the cross. The north and south sides are undecorated.

East Face

In the photo to the right the west face of the cross is shown. In the to photos below the East Face of the head is pictured on the left and the West Face on the Right.

Shaft: There are two panels of interlace.

Head: The crucifixion. Christ, dressed in a loin-cloth has Stephaton and Longinus on either side, though these figures could also be identified as Mary and John. Above his head there is a knot of interlace and above that a broken panel.

West Face

Shaft: The shaft is too worn to identify any decoration.

Head: There seems to be another crucifixion scene on this face, as on the East Face. It is unusual to have crucifixion scenes on both faces of a cross. As on the East Face the figures under each of his arms could be either Stephaton and Longinus or Mary and John. On this face Jesus is robed to the knees and it appears there is a boss on his abdomen.

Two Crucifixion Scenes

Veelenturf suggests that the two images of the crucifixion have different focuses. He writes: “On its west face we have the Crucifixion, to judge from the faint depiction of the assistant figures of Stephaton and Longinus. The east face displays the cruciate eschatological Christ.” (Veelenturf, 2003 p. 151) In describing what he refers to as the “Cruciate eschatological Christ” he writes: “This is a more symbol-like or ‘abbreviated’ rendition of the eschatological Christ figure, which is rather different from the “Osiris: Christ figures on the high crosses. He stands upright, with outstretched arms, in the pose of the Crucified. Yet, it is clear that Christ is not depicted as being crucified, for the usual assistant figures are lacking, and sometimes is is precisely the counter-image of this cruciate Christ figure that represents the Crucifixion!” (Veelenturf, 2003 p. 150) The significant difference between Veelenturf’s interpretation and that of Harbison hinges on whether Stephaton and Longinus, or perhaps Mary and John are depicted on each face of the cross-head or only on the west face. It is difficult to view the photos provided by Harbison and by Veelenturf and not see the possibility of the figures of the assistants on both faces.

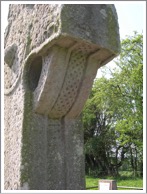

Ballyogan or North Cross

The following description is based on the work of Harbison (Harbison, 1992, pp. 96-97)

This granite cross is missing the bottom portion of the shaft. It now stands 4’ 9" (1.45m) tall and measures 29” (74cm) across the arms. The base is also incomplete.

The cross has roll mouldings along the edges and panels are framed by moulding.

East Face:

Base: There are two panels, the lower having interlace, the upper with an angular fret pattern.

E 1: David as Harper

E 2: The Sacrifice of Isaac

E 3: The Lord Reproves Adam or Eve Gives the Apple to Adam. A figure on the left has a hand on the stem of the tree. Adam is on the right. Both figures are clothed.

Head: The Crucifixion. The layout is traditional with Stephaton and Longinus and what appears to be an angel above each of Jesus’ arms.

Ring: There is a “battlemented” line in the center. This refers to a pattern similar to the notching on the parapet of a fortified wall.

South side

Base: There is a panel of interlace on the portion of the base that can be clearly defined.

Shaft: There is a panel of “interlocking angular C-shaped spirals.”

Ring and Arm: “There is a vertical groove in the centre of the lower and upper segments of the ring, and the end of the arm is undecorated.”

West Face: This face of the cross is badly deteriorated.

Base: Each of two panels contains a “ringed cross in raised relief.”

W 1: The Visitation. Two figures embrace each other. They are presumed to be Mary and Elisabeth.

W 2: “Interlinking S-spirals with small bosses interspersed among them.”

Head: “The S-spirals of the shaft reach up into the centre of the head, and there are knots of interlace on the arms.”

Top: The Annunciation to Mary. The angel on the left announces Jesus’ conception to Mary.

Ring: The ring may be similar to that on the east side

North Side:

Base: Each of two panels have interlace.

Shaft: There is irregular free pattern.

Ring: A vertical groove decorates the outside of the ring.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 53 B 2. The Duiske Abbey is in the center of town. The crosses are located behind the church.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted:

Ballyogan House: http://www.ballyoganhouse.com/graiguenamanagh.php

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Veelenturf, Kees, “Visions of the End and Irish high crosses” in Masrtin McNamara (ed.), Apocalyptic and Eschatological Heritage: The Middle east and Celtic Realms, Dublin-Portland, 2003, 144-173.

Kilkieran Crosses (Castletown)

Nothing is known of the history of the Kilkieran site. Even the founder/patron of the monastery is not clear. The name Cill Ciarain means Ciaran’s church, but which Ciaran is not clear. There was Ciaran of Clonmacnoise, Ciaran of Saighir (Sierkeiran in Co. Offaly) and possibly other Ciaran’s as well. (Roe, p. 35) Ciaran of Saighir was patron saint of Ossory which suggests the possibility that he was at least the patron saint of Kilkieran, if not the founder. (Edwards p. 5) The photo to the righty shows the Kilkieran cemetery.

Ciaran of Saighir is said by some to have been born in the late 5th century and to have died in about 530. He is sometimes listed among the Twelve Apostles of Ireland, who preceded Saint Patrick as Irish saints. (http://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=4173, 2/2017)

A partial excavation in 1985 explored five trenches along the north side of the site. What it found was the remains of a ditch along with a possible bank and wall. These are of uncertain date and could be early Christian (400-800) or Medieval (800-1169). The location and enclosing wall are typical of early ecclesiastical sites. (Hurley p. 132)

Edwards has offered an extensive assessment of the possible dates for a group of Ossory crosses that include Kilkieran East and West. She suggests dates at the end of the 8th or the beginning of the 9th century. (Edwards, p. 32) This would be consistent with the possible dating of the enclosure to the late Early Christian or early Medieval periods.

The Crosses

There are three crosses and fragments of a fourth cross at Kilkieran. One is mostly undamaged while two were smashed and prostrate in 1851 and repaired in 1858. (Roe, p. 35) The descriptions below represent a combination of the observations of Roe and Harbison. (Roe, pp. 35-41 and Harbison, 1992, pp. 117-120)

The North or East Cross

This cross is also referred to as the Tall Cross. Roe identifies it as the North cross and Harbison as the East cross. By whatever name, it is unique and easily identified on the site. It stands 10’ 6” (3.2m) tall and has very short arms that span only 17” (43cm). The cross sits on a round base that has a diameter of 4’ (1.25m) and is 14” (35cm) high. The shaft measures 10.5” x 9.5” (27cm x 24cm) where it meets the base. There was once a cap as the tenon still exists on the top of the shaft. Hatched moulding outlines the shaft and arms. There are faint traces of ornament and an “equal-armed cross “ seems to be on the end of the south arm. (Roe, p. 37)

East Face: (See photo to the right.) While the decoration is difficult to identify, Harbison suggests that in a square panel at the crossing there is a St. Andrew’s cross. (Harbison, p. 117)

West Face: (See photo to the left.) On this side only there are semicircular notches on each side above and below the crossing. Ornamentation is difficult to make out. (Harbison, p. 117)

The South or East Cross

Harbison identifies this as the south cross while Roe names it the east cross. It is 6’5” (1.95m) tall and sits on a base that is 15” (39cm) high and measures 37” (95cm) square at ground level. The arm span is 40” (1.02m) and the shaft measures 13” x 11” (34cm x 28cm). The base is a truncated pyramidal shape. The ring is perforated and quite plain.

The cross itself is bordered by a wide flat moulding and there is a boss at the center crossing on both sides. The only decoration consists of some incised lines that run horizontally around the beehive shaped head.

The two faces, east on the left and west on the right are shown in the photos.

The West Cross

This cross stands 8’ (2.45m) tall and sits on a base that is 26” (67cm) high and measures 4x” x 43” (1.18m x 1.10m) at ground level. The cap adds another 19.5” (50cm). The cross is 42.5” (1.08m) across the arms and the shaft measures 18” x 16.5” (45cm x 42cm) where the shaft meets the base.

East Face

Base: The lower tier of the base has two panels, each of which contains four horsemen. The middle step has “knots of interlace at intervals, joined by one strand top and bottom and the same is found on all the other faces of the base.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 118) The upper level of the base is badly damaged all around.

Base: The lower tier of the base has two panels, each of which contains four horsemen. The middle step has “knots of interlace at intervals, joined by one strand top and bottom and the same is found on all the other faces of the base.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 118) The upper level of the base is badly damaged all around.

E 1: Tightly woven interlace.

E 2: Spiral decoration that may have animal ornament.

Head: Five bosses stand in a background of interlace. One is in the center of the crossing, the other four sit astride the ring, one on each arm, one above and one below the center.

Ring: Each arc of the ring has a panel of interlace framed by roll moulding.

South Side

Base: There are two panels outlined in roll moulding. That one the left has four interlace panels causing a sunken cross to form between them. The panel on the right has nine smaller panels of interlace.

Shaft: There are vertical panels of interlace separated by raised ribs that are badly damaged.

Underside of Arm: Decorated with interlace.

End of Arm: Two square panels, one inside the other are decorated on the interior by interlace.

Top: There is one vertical panel with interlace.

West Face:

Base: The lower tier has three panels, each framed by roll moulding which in turn is outlined by rope-moulding. The center has a spiral pattern and the two flanking panels have interlace. The panel on the right has three vertical panels of interlace and that in the center seems to come unravelled at the bottom.

W 1: Two vertical animals cross at the neck and hug a cross.

W 2: Six interlinking spirals.

Head: Similar to the east face of the head.

Ring: Similar to the east face of the ring.

North Side:

Base: There are two panels framed by roll moulding and enclosed by rope-moulding on the top and bottom. On the left are circular motifs that include marigold patterns in each lower corner. The interlace on the right panel seems to come unraveled in the lower right corner.

Shaft: The moulding is rope-like and the panel has a field of loose interlace.

Ring, arm and top: These are similar to the south side with the exception of the end of the arm. It has “a pattern made up of a number of wheel-like devices.” (Harbison, p. 119)

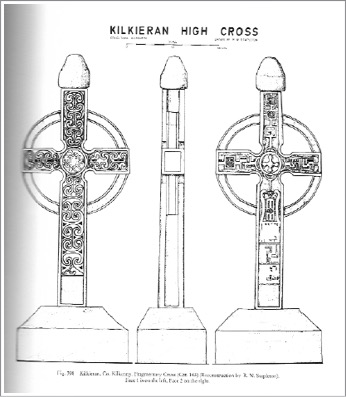

Fragmentary Cross

Four fragments of a fourth cross were found on the site. Only one, a part of the shaft remains on the site. The cross, as reconstructed on paper by Richard Stapleton of the Office of Public Works, was over 7 and one half feet tall and just short of 4 feet across the arms. Describing the cross is difficult without reference to Stapleton’s drawing, which is pictured below. (Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 398)

Face 1

With reference to the illustration above, Harbison describes what he refers to as Face 1, on the left above. At the center of the cross is a circle with 2 raised ribs that enclose a group of conjoined spirals that surround a now uncertain feature. Both the arms and the shaft are decorated with pelta shapes that are joined vertically and horizontally. (Harbison, 1992, p. 119)

Face 2

Once again, referring to the above illustration the shaft contains a number of square panels. Most of the decoration is destroyed but there are shapes that may have been meander or L-shaped fields in the corners of the panels. Near the top of the shaft, just below the ring is a panel that has “three parallel upright bars, interrupted almost half-way up by a sunken cross shape.” On each side of the bars is what may have been serpents. Their heads lean together at the top. In the center of the head is an equal armed cross. On the arms are whorls and swastikas. On the upper shaft is a panel with L-shapes in the corners around a central square. (Harbison, 1992, pp. 119-120)

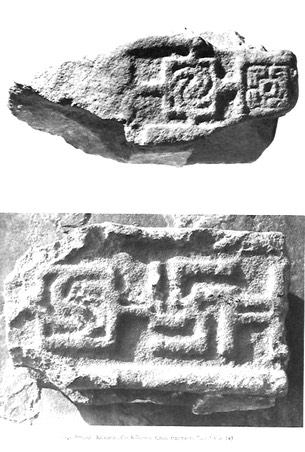

The photos here illustrate the shaft that remains on site at Kilkieran. The east face is pictured to the left and the west face to the right.

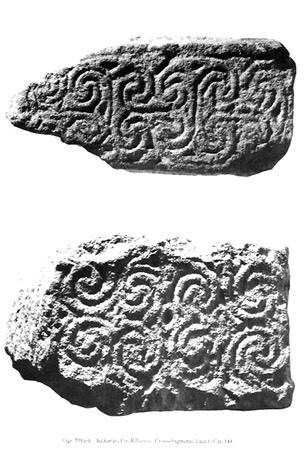

The photos below represent the other fragments of the cross, now on display in the Reception area of the Jerpoint Abbey. See the photo below to the right.

The photo to the left illustrates the lower side of the head of the cross seen in the photo below right. The photo below left shows the same face of the cross illustrated in the photo below right. (Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Figs. 394, 395)

The photos below show the decoration on both sides of the fragments added to the head in the Jerpoint display. In each case the top photo represents the arm that extends toward the top of the photo above. In each case the lower photo illustrates the two faces of the larger fragment that extends to the right in the photo above. (Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Figs. 398 a-b left; c-d right)

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 52 4 G. Located north of Carrick on Suir near the intersection of the R697 and the R698.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Carrigan, William, “The History and antiquities of the Diocese of Ossory”, Vol. IV, Dublin, 1905.

Crawford, Henry, S., “The Crosses of Kilkieran and Ahenny”, The Journal of the royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 39, No. 3 S[Fifth Series,Vol. 19] (Sep. 30, 1909), pp. 256-260.

Edwards, Nancy, “An Early Group of Crosses from the Kingdom of Ossory”, The Journal of the royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 113 (1983), pp. 5-46.

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Hurley, Maurice, F., “Excavations at an Early Ecclesiastical Enclosure at Kilkieran, County Kilkenny,” The Journal of the royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol, 118 (1988), pp. 124-134.

Kelly, Dorothy, “The Capstones at Kilkieran, county Kilkenny”, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 115 (1985), pp. 160-162.

Roe, Helen M., The High Crosses of Western Ossory, Kilkenny Archaeological Society, 1976.

Saint Ciaran of Saigir: http://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=4173

Killamery

The Monastery and Saint

Tradition reports that a monastery was founded at Killamery in the early 7th century by a Saint Gobban Fionn. The monastery is reported to have grown to house 1000 monks. As Roe points out, this may reflect the size of the foundation in the 9th century, during the time the high cross was carved. (Roe, p. 43) Little else is known of the history of the foundation. It appears once in the annals of the Four Masters at the year 1004 where it is recorded that “Domhnall, son of Naill, Abbot of Cill-Lamhraighe died.” The photo to the right below shows the site.

Saint Gobban Fionn was a member of the Ui Laine, a clan in the south of Ireland. His first monastery was established at Leighlin. St. Gobban moved from there, leaving St. Laserian as Abbot. Leighlin became a monastery of as many as 1500 monks. After leaving Leighlin, Gobban established the monastery at Killamery. It is possible that he took a church that had been established by Lam or Lam-Aed, a servant of St. Patrick who, as a groom, stole a horse and was later forgiven and blessed by Patrick, as the starting point for his foundation. This conjecture is based on the fact that the old name was Cill-Lamraighe or “the church of the descendants of Lam.” What is clear is that St. Gobban became the patron saint of the monastery. (Stokes, p. 569) Late in his life Gobban left Killamery and moved to the monastery at Clonenagh where he died and was buried. (Carrigan, p. 45)

The Cross

The High Cross at Killamery is carved from “pale silicious sandstone” (Stokes, p. 572) It stands 12’ (3.7m) tall and measures 3’ 10” (1.2m) across the arms. In describing the decoration below I follow Harbison’s descriptions, and all praises in quotation marks, except where noted, are his. (Harbison 1992, pp. 121-123)

East Face

See the photo to the right.

Base: The lower step has a row of crosses. The upper step decoration is worn but on the left “there would appear to be a man sticking out his arm in the midst of birds and other animals.

Plinth: An “incised line running parallel to the edges”.

Shaft: Three Marigolds are the dominant pattern. There are triquetra knots in the spaces around the marigolds. See photo to the left.

Head: A central boss has interlace below that emerges into serpents which stretch their heads onto the arms of the cross with serpents stretching from above. See the photo to the right.

Top: Roe offers a colorful description of the image on the top cross arm describing it as “the strangest of all the freakish creatures of Irish invention. This, a google-eyed shaggy little monster, hangs head downward and is seemingly cleft from head to tail, its nostrils, paws and legs lying flat on either side of its body, its tail squashed fanwise.” (Roe, p. 48) See photo to the left.

Ring: The bottom right has interlace and the bottom left has rope moulding. The other segments are no longer clear.

South Side

See the photo to the right.

Base: The lower segment has three panels. The left panel has interlace, the others are weathered beyond recognition. The upper step has what seems to be a “cross-shaped panel possibly bearing a human interlace surrounding a sunken cross within it.” The right may contain interlace.

Shaft: The plinth has “a roundel decorated with interlace”. The shaft has three vertical panels with interlace on the shaft that becomes spirals under the arm and changes again to interlace at the top of the shaft.

End of Arm: Noah’s Ark. The ark features a steering oar, four figures on a lower deck and above a dove that may hold an olive branch. See photo to the left.

West Face

See the photo to the right.

Base: The lower step has several panels. The center panel has two crosses that share a common arm and a lozenge or spiral decoration. Left of this is a panel of interlace that forms a cross. On the right is another panel of interlace forming a cross. On the far left there are interlinked squares. Other panels are too worn to be identified. The upper shaft has “three groups of two bosses, probably with spiral and trumpet decoration between them.”

Shaft: See the photo to the left. The plinth has a rectangular panel. It may have had an inscription and Macalister interpreted it as reading “Prayer for Maelsechnaill” The person referred to cannot be identified with any certainty, but Harbison notes that a Maelsechnaill of the mid ninth century was “one of the first Irishmen who could lay claim to the title ‘King of Ireland’, which he records obsessively on the crosses” (Harbison, 1999, p. 165). It should be noted that no one has been able to verify Macalister’s reading of the inscription.

W 1: Diagonal fretwork. Roe describes this as “a simple incised key diaper” (Roe, p. 44) In this case diaper referring to a repeated geometric or floral pattern.

W 2: “Vertically-structured fretwork with diagonal lines interspersed.”

Head: At the center of the head is a design that Harbison describes as a whorl, Stokes describes as a spiral design and Richardson describes as a whirling disc. See the photo to the left. Richardson comments that the whirling disc is similar to a design at the center of the head of the cross at Moone pictured to the right. (Stokes, p. 573; Harbison, 1992, p. 123; Richardson p. 23)

Below this is a scene Harbison identified as God blessing the seventh day. Roe saw in this image a traditional depiction of the crucifixion. (Roe, p. 44) See the photo to the left.

The north arm shows a hunting scene with horseman, stag and dog. Roe suggests a religious symbolism to this scene interpreting “the pursuit of the stag as typifying the sinful soul hunted by Christian Virtues . . . as the hounds and the hunter, possibly a bishop, who drives it at the last into the safety of the Church.” (Roe, p. 45) The south arm shows a chariot procession with human figures above and animals beneath. Roe suggests this might represent the “translation or acquisition of relics”. (Roe, p. 45)

Above the whorl is a scene that may depict Adam and Eve at Labor.

Top: There are interlinked squares that offer “positive or negative cross-patterns.”

North Side: (See the photo to the right.)

Base: On the lower riser there is a “stepped pattern in relief” with “geometrical decoration in the background”. On the upper riser there is no decoration.

Shaft: On the plinth is a rectangle. The shaft is divided into three vertical panels. The central panel has interlace that changes slightly on the ring and returns to the original pattern on the upper part of the shaft.

End of Arm: There are four squares, just visible in the photo to the left, that can be identified as follows: Top left may be St. John the Baptist Embracing Christ; Top right Salome Dancing for the head of John the Baptist; Bottom left the Naming of John the Baptist and Bottom right Zacharias and Elizabeth with the infant John the Baptist. See the photo to the left.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 52 3 F. Located just east of the N76 just north of Ninemilehouse.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Carrigan, William, “The History and antiquities of the Diocese of Ossory”, Vol. IV, Dublin, 1905.

Harbison, Peter, The Golden Age of Irish Art: The Medieval Achievement 600-1200, 1999.

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Richardson, Hilary, “Number and Symbol in Early Christian Irish Art”, The journal of the royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 114 (1984), pp. 28-47.

Roe, Helen M., The High Crosses of Western Ossory, Kilkenny Archaeological Society, 1976.

Stokes, Margaret and Westropp, T. J., “Notes on the High Crosses of Moone, Drumcliff, Termonfechin, and killamery”, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Vol. 31 (1896/1901), pp. 541-578.

Kilree

The Monastery

The origins of the monastery at Kilree are unknown. Tradition suggests the monastery may have been founded as early as the 6th century. It is associated with St. Rhuidche, who may have lived there. What we do know with some confidence is that the high cross is 8th or 9th century. Carrigan dates the ruined church to the year 1000 or before. He notes that its characteristics are strongly Celtic. (Carrigan, p. 47) The church is pre-Romanesque and has a pronounced antae. The round tower probably dates from the 11th century. The photo to the right shows the east face of the cross. It was taken from the area of the round tower and church.

It is possible that the round tower, which sits on the circular boundary wall of the old churchyard represents the inner circle of the monastic enclosure. “A 9th-century sandstone High Cross . . . in an adjoining field, west of the tower, may indicate that this was a bivallate complex.” (Lalor, p. 173)

There are several theories related to the origins of the name Kilree. Carrigan rejected several of these including: 1) the name derives from “Church of the King”; 2) the name derives from the Gaelic word farce meaning heath; 3( the name derives from a saint named Fraech, who is listed in the Martyrology of Donegal. Carrigan prefers the tradition that the name derives from St. Ruidhche (pronounced Ree), a female saint listed in the Martyrology of Donegal, Ruidhche the Virgin. In addition, the parish and church have St. Bridget of Kildare as patron. (Carrigan, p. 45)

The Cross

The description of the cross is taken largely from Harbison, 1992, pp. 133-134. The cross is carved of sandstone. It stands 7’ (2.15m) in height and measures 3’ 7" across the arms. The base is 20” (50cm) tall and measures 45” x 42.5” (1.15m x 1.08m) at ground level. The shaft measures 18” x 14” (45cm x 35cm) where it meets the base. There are roll mouldings on the edges and there is no horizontal separation between panels. The ring is perforate.

East Face

Base: The lower step has geometric decoration while the upper step is too worn to identify any decoration that may have been there.

Shaft: The shaft has a fretwork pattern on the lower section and a “dense fret-spiral” on the upper portion.

Head: There is a large domed boss at the center with a ring of broad interlace surrounding it and this is encircled by a roll moulding.

Arms: There is a hunting scene composed of very small figures and animals. This is not evident in the photos.

Top: There are “linked squares with sunken centres.”

Ring: Each segment is enclosed by roll moulding and contains interlace.

South Side

Base: There is a meander decoration on the lower step. The upper step may have contained figures but they are now too worn to identify.

Shaft: There are three vertical panels divided by ribs. “The middle panel contains fretwork, that on the right contains interlace, but that on the left is now very worn.”

Ring Underside: The pattern on the shaft continues on the ring. See the photo to the right.

End of Arm: See the photo to the left. There are four panels formed by a cross with a circle in the center. The scene at the top left is unidentified. It has been suggested it may represent Saints Paul and Anthony receiving bread or Salome dancing on the left for the head of John the Baptist. The top right contains a lion. The panel on the bottom left has been tentatively identified as St. John the Baptist Embracing/Recognising Christ. The bottom right seems to represent the beheading of John the Baptist.

West Face (See the photo to the right.)

Base: The decoration is too worn to make out.

Shaft: This too is worn but has two sections with the upper one containing a pattern of circles of different sizes. In the center of this upper panel is a small boss.

Head: A scene at the bottom of the head seems to represent the Adoration of the Magi. The center of the head has a large domed boss surrounded “in turn by a broad ring of interlacing and a raised circular moulding. There is a smaller boss surrounded by a spiral coil on each arm. There is yet a further one on the top of the cross which has the coil changing directions to form the upper part of an S-spiral with lobed terminals.”

Ring: The ring has interlace between raised mouldings.

North Side

Base: “The upper part of the base has a panel of negative and positive squares arranged to form sunken squares and T-shapes.”

Shaft: Like the south side, there are three vertical panels. The central panels is interlace and changes style on the underside of the ring. The side panels contain fretwork and spiral scrolls.

End of Arm: This was probably also divided into four panels. The bottom left seems to have a fretwork pattern.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 52 2 G. Near a minor road that runs south from the Kells Priory.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Carrigan, William, “The History and antiquities of the Diocese of Ossory”, Vol. IV, Dublin, 1905.

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

High Crosses.org: http://highcrosses.org/kilree/index.htm

Kilkenny People: http://www.kilkennypeople.ie/news/kilkenny-news/60540/The-secrets-of-the-trio-of.html

Lalor, Brian, "The Irish Round Tower", The Collins Press, Cork, Ireland, 1999.

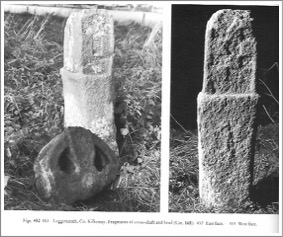

Leggetsrath

St. Malach was active in Waterford, around Lismore, and also in Kilkenny. There is a ford near Kilkenny called Aghmalog or “Malog’s ford.” There is an ancient manor there called Kilmalog that is now known as Leggetsrath, meaning “the Legate’s rath.” This was the site of an ancient church that occupied an even older rath site. The only remains are the shaft and head of a granite cross.

Malach is associated with St. Patrick, and so considered a very early saint of the Irish church. It is told that he refused to raise a dead man and that as a result Patrick told him his house, or monastery, would be small. This may reflect the fact that by the ninth or tenth century the foundations established by or dedicated to St. Malach were either quite small or had disappeared. pp. 395-6

The Cross

There is a partial cross shaft and a cross-head at the site. The shaft stands about 4’ (1.2m) above the ground surface. The faces are about 18” (46cm) wide and the thickness of the shaft is just short of 14” (36cm). The shaft has two parts, the lower wider than the upper could be described as a base. The upper portion has roll moulding on the edges. (Harbison, 1992, pp. 135-136, photos above right Harbison Vol. 2 Figs. 452-453)

West Face: There are the remains of a chequered-pattern on the upper portion of the shaft.

East Face: There is a plain Latin cross in relief on the upper portion of the shaft. (Shearman, p. 397)

Head Fragment: This fragment is is about 19” (48cm) high and 27” (69cm) across, the lower portion of the head being broken away. Each face has a domed boss, one is about twice as large as the other. (Harbison, pp. 135-136) When I visited the brambles around the shaft and head were so thick that I could not see the head.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 52 1 H. Located just east of Kilkenny. From the N10 take the R712 east a little over 0.6km. Turn north on the L26311. The cross shaft is in a field directly behind an industrial park to the east of this road.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Shearman, John Francis, “Loca Patriciana No. VIII,” The Journal of the Royal Historical and Archaeological Association of Ireland, Vol. III, Fourth Series, 1876, Dublin

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Thomastown

The Site

For most of the information that follows, I am indebted to Ruth McCann at the Kilkenny Library and Lynda Browne of Failte Ireland. They provided me with a Copy of “The Thomastown high cross — a Cornish Connection” by Etienne Rynne.

The cross at Thomastown lies just outside the traditional date of 1200 as the terminal date for the carving of the Irish High Crosses. As Rynne points out, it also differs in morphology from the Irish High Crosses, having a closer relationship with some of the crosses in Cornwall in England, of the same general period. This cross is not listed by Harbison. It is included here because it is included in Henry Crawford’s list of crosses and because of its similarity to the cross at Dunnamaggan, described above, and its possible proximity in time to the production of the late Irish High Crosses.

Rynne provides historical background that is briefly summarized below. In the late 12th century William Marshall was lord and master of Leinster and justiciar of Ireland. The justiciar was somewhat similar to the modern prime minister. He granted the land where Thomastown now stands to Thomas fitz Anthony, after whom the town is named.

Thomas fitz Anthony was a significant person in his own right and was seneschal, or steward of Leinster. He founded an Augustinian Priory at nearby Inistioge in about 1206 and built Greenan castle on the bank of the river Nore nearby. Not long after he founded a church on the opposite side of the river from his castle and a town grew up around it. The church was the parish church of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, popularly known as St. Mary’s.

At some point in time a cross was erected in the churchyard. It is of the Cartwheel type. It has an unpierced ring and is of unknown date. The cross is not complete. The remains of the circular head was erected on a concrete shaft. Whether it sits on the original spot for the cross is uncertain. It has been speculated that the cross was erected to mark the church’s foundation. It true, that would place its carving in the early thirteenth century.

“The Thomastown cross does not fit into any of the normal types of high cross found in Ireland.” (Rynne, p. 18) There are parallels in southeast Cornwall. Like the Thomastown cross there are several crosses there that are “wheel crosses, i.e. disc-headed crosses quartered by sunken panels resulting in low relief equal armed crosses within a ring.” (Rynne, p. 19)

Rynne identifies a number of crosses in Cornwall that are similar to that at Thomastown. She also suggests that a thirteenth century date could be claimed for these crosses as well.

Rynne then addresses the question of why a cross similar to those of Cornwall would be found at Thomastown. Her response is that there was significant ecclesiastical leadership in the Thomastown area from Cornwall during the early 13th century with direct connections to Bodmin in central Cornwall.

Bodmin, meaning “home of monks” in Cornish was the location of a monastery that was founded at Padstow, around 518 by St. Petroc, who came to Cornwall from Ireland. Following a Viking raid in 981, most of the community moved over to Bodmin. In the 12th century the Canons Regular of the Lateran, or the Augustinian Canons, established a priory in Bodmin. (https://stmarysbodmin.org.uk/st-marys-bodmin/)

Rynne concludes “As will be appreciated, the Cornish connection with the area was immensely strong, especially when it is realized that Geoffrey fitz Robert’s charter, granting lands and privileges to the priory of Kells, ordained that all priors at Kells were to be elected by the canons from among their own numbers or from the mother-house of Bodmin — and that priors continued to be elected from Bodmin until the beginning of the fourteenth century.” (Rynne, p. 19) Describing the importance of this she goes on to state “Not only is Kells priory about six miles from Grenan castle, Thomas fitz Anthony’s head-quarters and Inistioge priory, which he founded, is only about four miles distant from it, but the possessions of Kells priory included the parish of Dysert, near Thomastown. Surrounded as he was by such Cornish influence and with a strong Cornish bishop in Kilkenny advising him, surely . . . Cornish influence played an important role.” (Rynne, p. 20)

The Cross

The cross-head is carved from granite stone that is “dull reddish/purplish in colour.” (Rynne, p. 18) The original diameter was about 25” (63.5cm) and the cross-head is over 10” (25cm) in thickness. On each face the head is quartered creating equal size sub-triangular arcs. These are cut away to create an equal arm cross and leaving a raised ring about the head. The two upper quadrants have broken away, leaving only a short fragment of the ring on one side. The ring seems to have a shallow groove on each face that suggests flat moulding on either side. A short section of shaft is preserved measuring about 5” (13cm) in length.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 52 2 H. Located at Thomastown south of Kilkenny. See the map to the left for the location of high cross in Thomastown.. The cross is in the old church ground and graveyard which is now a private residence. The cross can plainly be seen and photographed through the gates.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Rynne Etienne, “The Thomastown High Cross — A Cornish Connection”, Kilkenny: Studies in honour of Margaret M. Phelan, John Kiran, Ed., Kilkenny Archaeological Society, 1997.

St. Marys Bodmin: (https://stmarysbodmin.org.uk/st-marys-bodmin/)

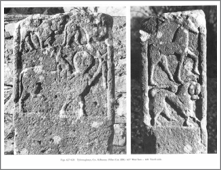

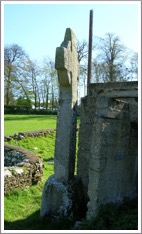

Tybroughney pillar or shaft

Saint Modomnoc is said to have lived in this area as a hermit in the 6th century. There was a Viking settlement here that was destroyed in 980. A church was built on the site before the Norman invasion of Ireland, and shortly afterward a castle was built here by Prince John of England. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tybroughney)

Saint Modomnoc (d. c. 550) was a disciple of St. David of Wales. He was related to the Irish family of O’Neil and the last years of his live were spent as a hermit in Kilkenny. (Bunson, p. 592)

The Stone:

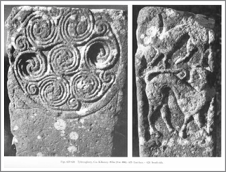

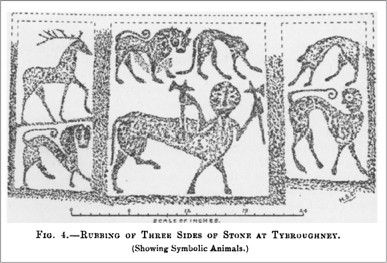

(The photos are found in Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, figs. 225-228) From left to right these show the East Face, the South side, the West face and the north side.

It is uncertain whether this stone was part of a high cross. Crawford argues that it may well have been part of the shaft of a high cross that was broken and had the top smoothed to be used, probably as a grave marker. (Crawford, pp. 271-272)

The material from which the object is carved is a coarse brown sandstone. All of the carving is on the upper portion of the slab and extends to 18" or 19” (46cm or 48cm) below the present top. (Crawford, p. 272) The descriptions below are taken largely from Crawford. The identification of the directions related to each face and side follow Harbison. The photos above show the South face on the right and the North face on the left.

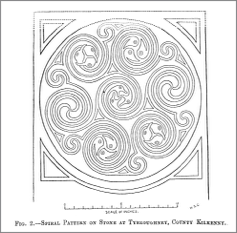

East Face

Crawford offers a detailed description of the single carving on this face. It reads in part: “The south side bears an elaborate and finely executed trumpet or spiral pattern, consisting of six sets of spirals arranged in a circle, with a seventh of the same size in the centre; all these are interlocked in threes, that is adjacent pairs are connected with each other and with the centre one.” (Crawford, p. 272) His description goes on and is quite detailed. He provides the line drawing of the panel as reproduced above. (Crawford, p. 271)

North Side:

There are two figures. The upper figure is a stag, said to represent Christ because of its enmity to serpents. The lower figure is a lion, interpreted in the Bestiary as a symbol of resurrection because the cubs were believed to be born dead and on the third day the lion breathed life into them. (Crawford, pp. 273-274; illustration below p. 274) These are the images to the left in the drawing below.

West Face

Three animals appear on the north face, as illustrated in the center of the drawing above. The lower is a centaur that holds an ax in each hand. The centaur was seen as representing the contest between good and evil. Above and to the left is either another lion or possibly a bull. The figure to the right appears to be of the cat family, but has lost its head. (Crawford, p. 274)

South Side

On the west side are two additional animals. The lower figure is a manticora with the head of a human, the body of a lion and the feet of an elephant. It was a symbol of death. The upper figure is damaged but Crawford ventured to guess it was a hyena, a symbol of the devil. (Crawford, pp. 274-275)

Based on these identifications, Crawford concludes “We should then have the emblems of Christ and the resurrection on the right side of the stone, balanced by those of the devil and destruction on the left, while between them is the centaur, typifying the contest between the forces of good and evil.” (Crawford, p. 275)

It should be noted that Harbison identifies the sides of the piece differently than Crawford. In Harbison, Crawford’s south face becomes the east face; the west side becomes the south side; the north face becomes the west face; and the east side become the north side. (Harbison, 1992, pp. 179-180)

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 52 4 G. Located about 2km southwest of Piltown along the South Leinster Way. In Piltown, about 100m west of Anthony’s Inn there is a sign for the South Leinster Way. About 2km down that road you will come to Tybroughney House on the right and two circular stone columns on the left. An old graveyard “Tybroughney Graveyard and Church” is down the field to the right near a pedestrian railway bridge. See map to the right.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Resources Consulted

Bunson, Matthew, Margaret and Stephen. “Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints”, revised. Huntington, Indiana, 2003. https://books.google.com/books?id=l-pwoTFp31kC&pg=PA592#v=onepage&q&f=false

Crawford, Henry S., “Description of a Carved Stone at Tybroughney, Co. Kilkenny”, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. Fifth Series, Vol. 38, No. 3, [Fifth Series, Vol 18] (Sep. 30, 1908), pp. 270-277.

Harbison, Peter, 1992, The High Crosses of Ireland: an Iconographical and Photographic Survey, 3 vols. Dublin. Royal Irish Academy. Bonn. Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH.

Tybroughney: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tybroughney

Ullard

A monastery was founded at Ullard by St. Fiachre in the 7th century, though ecclesiasticalireland.org dates it to the 6th century. The ruined Romanesque church on the site (see photo to the left) was built in the 12th century.

There were at least three saints named Fiachre, a common problem. The most famous St. Fiachre lived in Ireland and later moved to France and established a monastery at Meaux. This may, however, not be our Fiachre. An article in wikipedia.org quotes Donnchadh O’Corrain in his Gaelic Personal Names as identifying a St. Fiachra who is listed as Abbot of Urard in County Carlow and a St. Fiachra who was Abbot of Clonard. There is an Urard in County Tipperary but O’Corrain may well mean Ullard, which is close to the borders with both Laois and Carlow but in Kilkenny.

The Cross

The following description relies heavily on the work of Harbison. (Harbison, 1992, pp. 183-4)

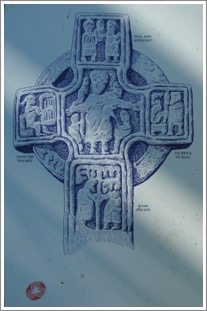

Three fragments of the cross have been erected at the northeast end of a handball alley that is attached to the church at Ullard. The first fragment, the base is about 3’ (90cm) in height and measures 3’ 6” x 31” (1.05m x 80cm) at ground level. The lower part of the shaft stands another 37” (93cm) in height and measures 18” x 14” ()45cm x 36cm) where it meets the base. The head, which is imperforate is 5’ (1.54m) high and 4’ 1” (1.25m) wide across the arms. A portion of shaft is attached to the head. The head and shaft are joined by a concrete shaft.

The sides of the cross are not decorated. On the base there is decoration only on the east face.

East Face

Base: There are three registers with the lower register divided into three square panels. From left to right these contain a knot of interlace, four interlinked knots of interlace and a four-legged spiral. Photo to the left from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 642.

The other two registers are each divided into two panels and contain interlace and spiral decoration.

Shaft: There are six figures depicted who are presumed to be Apostles.

Head: In a lower panel it is possible that the scene of Eve giving an apple to Adam is depicted. The image below left is found on one of the signs at the site, describing the cross. The image on the right shows the head of the cross in its present condition.

The center of the head contains a crucifixion scene showing Jesus in a long robe. In a variation from the usual, Longinus is on the left and Stephaton on the right. An angel is depicted above each arm.

The south Arm depicts David with a Harp.

The north arm depicts the Sacrifice of Isaac.

The upper arm seems to depict David encountering Goliath.

The ring was probably decorated but only a spiral ornament on the left-hand arc is visible.

West Face

The shaft is undecorated.

The Head: The panels are worn or damaged. In the center we may have Saints Paul and Anthony Breaking Bread in the Desert.

North Arm: There are two unidentified figures.

South Arm: This represents the Temptation of St. Anthony. A central figure is flanked by a demon with a human body and animal head on each side.

Top Panel: There are three unidentified figures. Two figures standing in profile hold a third figure upside-down between them. This scene could represent the Slaughter of the Innocents or the Judgment of Solomon, or Saints Paul and Anthony overcoming the devil.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 53 2 B. Located just east of the R705 on a minor road about 4km north of Graiguenamanagh.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Ullard: http://www.ecclesiasticalireland.org/ullard/index/html

Ullard Church: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ullard_Church

Vigors, Phillip, D., “The Antiquities of Ullard, County Kilkenny, 1892”, The Journal of the royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 3, No. 3 (Sep., 1893), pp. 251