The Crosses of County Offaly include: the Banagher shaft or pillar; Clonmacnois crosses, Drumcullin; Durrow cross head, west cross; Kinnitty or Castlebernard; Sier Kieran base, small cross; and Tihilly. The location of County Offaly is indicated by the red star on the map to the right.

Historical Background

What is now County Offaly (originally King’s County) was established in 1557. The current county includes parts of several ancient Irish Kingdoms. These include the Ui Failge, Mide (west Offaly) and Munster (south Offaly). (Kingdom of Ui Failghe)

Mesolithic Offaly (c. 8000 to 4000 BCE)

Stone axes, arrowheads and blades, dating to between 7160-6260 BCE have been found at Boora bog near Birr. Encampments were temporary as no structures have been found at the site. This site indicates the presence of habitation in the Midlands at a time when it was assumed the area was unoccupied. (Ryan, heritage council)

Neolithic Offaly (c. 4000 to 2000 BCE)

The Neolithic period saw the introduction of agriculture. Stone tools dating to the Neolithic have been recorded at a number of sites in County Offaly. (Kiely, p. 4)

Bronze Age Offaly (c. 2000 to 600 BCE

Bronze Age burial sites in County Offaly include cist graves, pit and urn burials, cremation cemeteries, barrows, ring-ditches and wedge tombs. Cooking places or Fulachta fiadh have been found in several locations. Roundhouses or partial round structures have also been recorded. (Kiely, p. 4-5)

Iron Age Offaly (c. 500 BCE to 500 CE

The presence of Iron Age habitation in County Offaly is demonstrated by the discovery of the Old Croghan Man. This bog body was found at Croghan Hill, north of Daingean in County Offaly. This is one of the bog bodies now on display in the National Museum in Dublin. It is believed that this man died between 362 and 175 BCE. He was wearing an arm-ring that was made from leather, fibres and four bronze mounts. (Lobell) Hillforts and linear earthworks are the most visible monuments of this period.

Early Medieval Offaly (c 400 to 1100 CE)

This period marks the beginnings of Christianity in Ireland. Ringforts are the most common monument from this period. During this time period all of the monasteries to be considered below were founded. It was during the second half of this period that the High Crosses to be considered below were carved.

As noted above, present day County Offaly was divided among several different Kingdoms. For simplicity’s sake this background will focus on the ancient kingdom of Ui Failge but also consider briefly the history of Mide and the impact of the Vikings in this area.

The borders of the Kingdom of the Ui Failge covered present day County Offaly east of Tullamore, the western parts of County Kildare and parts of northeast County Laois. The name of County Offaly derives from the name of the kingdom which appears variously as Ui Fhailghe, Ui Failge and Uibh Fhaili. The name is also preserved in County Kildare with the baronies of Offaly East and Offaly West. (Kingdom of Ui Failghe)

The Kingdom of Ui Failge takes its name from a king, Ross Failge, who may have been a son of Cathair Mor. Cathair Mor was reputed to have been High King of Ireland, sometime in the second century CE, though this disputed. (Rootsweb, Ui Failge) For example, John Ryan, in an article entitled “The Early History of Leinster” dated Cathair Mor to the first half of the fourth century. (Ryan, p. 20) Following Cathair’s death, Leinster was supposedly divided among his sons. These included the founders of the Ui Failge, Ui Bairrche, Ui Enechglais, Crich na cCedach, and Ui Crimthainn. Ryan notes that the genealogies of these founders was probably worked out after the fact and that most of them, with the possible exception of Ross Failge, were probably not sons of Cathair. (Ryan p. 20)

The Kingdom of the Ui Failge was a part of the province of Leinster but had its own kings. Ui Failge certainly varied in size across the centuries from c 300 to 1200 CE. As the map below indicates, the Ui Failge were bordered on the north by Mide and perhaps the southwest edge of Brega. These Kingdoms were dominated from the 5th century by the Southern Ui Neill. Thus the Ui Failge experienced encroachment at times from the Southern Ui Neill. For example, the Annals for 600/04 report that Conall, son of Suibhne, a king of Mide and member of Clann Cholmain of the Southern Ui Neill, killed Aedh Roin, chief of Ui Failghe. (Rootsweb, Ui Failge)

Ui Failge was bordered on the east and southeast by two branches of the Ui Dunlainge clan, the Ui Muiredaig and the Ui Faelain. In the southwest, the Ui Failge were near enough to Munster that they experienced at least periodic pressures from that direction. For example, in the Annals for 575/52 we read Cumasgach, lord of Ui Failghe, was slain by Maelduin, son of Aedh Beannain, King of Munster. (Rootsweb, Ui Failge)

The western portions of the present County Offaly were in the territory of the Kingdom of Mide. From about the year 500, Mide was under the control of the Southern Ui Neill. The Southern Ui Neill were descendants of Fiacha, son of Niall of the Nine Hostages. Beginning in the 5th century they were expanding into what would become Mide, the “middle kingdom.” At its most extensive Mide included Counties Meath, Westmeath, and parts of Cavan, Louth, northern Dublin, Kildare and Offaly.

Beginning in the late 8th century the Vikings began to make their presence known. Their raids extended into the area of the Ui Failge. For example, the Annals of the Four Masters for 842.6 records “A military outing by the foreigners of Dublin to Cluain Andobair and the enclosure of Killeigh was raided and Nuadu son of seine was martyred by them.” And the Annals of Ulster record that in 845.12 “an encampment of the foreigners of Dublin at Cluain Andobair.” (Downham) Whether this was one raid or two, Cluain Andobair was close to the monastery at Killeigh, one of the chief churches of the Ui Fhailge located on their western boundary. (F.J. Byrne, p. 617)

Ecclesiastical History

There were numerous early monasteries founded in what is now County Offaly, some among the Ui Failge and some among the Southern Ui Neill. Below are listed twenty-nine early sites. (Monastic Houses in County Offaly) (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_monastic_houses_in_County_Offaly Seven of these sites have High Crosses or High Cross fragments. Below, each of these seven sites are considered. There is background on the site and photos and descriptions of the crosses and cross fragments associated with each site.

The monasteries in the present County Offaly and, more broadly, those among the Ui Failge include Kildare, Durrow and Clonmacnoise. These were important monasteries that had patronage from various early Irish kingdoms. The patron saint of Leinster and one of the three patron saints of Ireland was St. Brigid, and her monastery at Kildare was located in Ui Failge territory but lies in the present County Kildare. The monastery at Kildare was granted its land and patronized by the Kings of Leinster. If the date for the establishment of the Kildare monastery is 490, the King who granted the land for the foundation would have been Fraech mac Finchada (died 495). The monastery at Durrow was founded by St. Colmcille, another of the patron saints of Ireland. Durrow was patronized by the Southern Ui Neill and lay in their territory. Just to the south of Durrow lay Killeigh monastery, as noted above one of the chief churches of the Ui Failge. The great monastery of Clonmacnoise was founded by St. Ciaran with the patronage of Diarmait mac Cerbaill (died c. 565) who was of the Southern Ui Neill and who became the King at Tara or High King of Ireland. However, Clonmacnoise lay in an area that was also close to or at times part of the Ui Maine. “From an early period the kings both of southern Ui Neill Tethbae and of Ui Maine were buried at Clonmacnoise.” (O’Croinin p. 232) St. Patrick, the third of the patron saints of Ireland, does not seem to have founded any of the monasteries in the present County Offaly. Followers of his, however, founded two monasteries, that at Craebheach was founded by Trian, a disciple of Patrick, and that at Rahan was founded by Camelacus, a Patrician bishop.

Early County Offaly Monasteries

Banagher Monastery, early site

Birr Monastery, early site, founded pre 573 by St. Brendan of Birr

Clareen Monastery, founded 6th century

Clonmacnoise Monastery, early site, founded in 544 by St. Ciaran

Clonmacnoise Abbey, early site, nuns

Clonsast Monastery, early site, founded late 7th century by St. Bearchan

Cluain-an-dobhair, early monastery, possibly in Co. Offaly

Craebheach Monastery, early site, founded c. 450 by St Trian, disciple of Patrick

Croghan Monastery, early site founded pre 490/492

Drumcullen Monastery, early site, founded pre 591

Durrow Abbey, early site, founded 556/565 by St. Colmcille

Gallen Priory, founded 5th century by St. Canoc

Kilbian Monastery, early site, founded 583, by St. Abban ?

Kilcolgan Monastery, early site, founded by St. Colgan son of Kellach

Kilcolman Monastery, early site, founded by St. Colman Niger

Kilcomin Monastery, early site, founded pre 669

Killagally Monastery, early site

Killeigh Priory, early site, founded pre 549 by St. Sinchell

Killyon Monastery, early site, nuns, founded 5th century by St. Ciaran

Kilmeelchon Monastery, early site, founded 5th century by St. Gussacht mac Milchon

Kinnitty Monastery, early site, founded by 557 ?

Lemanaghan Monastery, early site, founded c 645-6 by St. Managhan ?

Lusmagh Monastery, early site, founded 7th century by St. Cronan

Lynally Monastery Columban monks, founded c 590 by St. Colman Elo

Rahan Monastery, early site, founded c 590-635 by Camelacus, Patrician bishop

Rathlihen Monastery, early site, founded c 540 by St. Illand

Reynagh Monastery, early site, nuns

Sierkieran Priory, early site, founded 5th century by St. Ciaran

Tihilly monastery, early site, founded 5th century

Banagher: consisting of a shaft or pillar now located in the National Museum in Dublin.

Background:

Writing in 1853, Cooke tells a little of the history of the Banagher church. In the ninteenth century it was known as Kill-Regnaighe, and was located in the parish of Reynagh. The church and parish were named for St. Regnach or Regnacia, a sister to St. Finian who was at the monastery at Clonard. It was his understanding that Regnacia founded a religious house at this place, now present day Banagher, and served as abbess. He suggests that she likely died near the time of her brother’s death. St. Finian died in 563. (Cooke, p. 277)

Banagher sits at a strategic point on the River Shannon. It was for a long time one of the few places where the river could be crossed between Leinster and Connacht. (offalytourism.com)

It was Cooke who found the cross shaft in the church cemetery, and who later, due to damage to the stone, had it moved to Clonmacnois. He learned from locals that the shaft had stood near a spring that was dried up by the time he was there. (Cooke, p. 277)

The Cross

DU018-205—-. The high cross from Kylebeg or Banagher, Co. Offaly (OF021-003004-). Described by Harbison as "A cross shaft of sandstone which originally stood at Banagher, Co. Offaly, was removed by Cooke around the middle of the last century (1800’s). After his death, it was moved to Clonmacnois around 1870, and to the National Museum in Dublin in 1929, where it is now on display with the inventory number 1929:1497. It is 1.47m tall, and its tapering faces and sides have maximum dimensions of 40cm and 19cm respectively. All the corners have small roll moulding, and the panels which are all of different sizes are also framed by similar moulding. Damage to the two top side panels was probably caused by a secondary attempt to add a ring. A shallow mortise-hole on top is probably secondary also.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 25)

The shaft fragment stands 56.5 inches in height (143.5 cm) has a width of 14.5 inches (39 cm) and is 7 inches thick (18 cm).

Face One:

1:1 There are three panels. The lower panel begins at the bottom with two animal heads, the one on the right side has been damaged but the one on the left is clearly visible. Above this there is a pattern of two-strand interlace that resolves at the top of the panel into two figures seen in profile. Each has a pointed nose.The one on the left is holding the wrist of the one on the right. What appears to be their hair creates an interlace pattern between their faces. (See the photo on the left below right, the source of both photos of the Banagher cross is Harbison, 1992, Vol. 1 pp. 25-26; Vol. 2, Figs 65-68)

1:2 In the center panel there is a lion crouching. Its tongue is out and its tail is between its legs. In the upper left corner is a three point interlace. Another interlace is above the back of the lion.

1:3 This panel is a simple two-strand interlace.

Face Two:

2:1 This face also has three panels. The lowest panel contains an intricate design of four intertwined humans. Their legs are intertwined in the center with their heads reaching out to each of the four corners. Something like a ribbon weaves around their arms.

2:2 The middle panel depicts a deer with the front right leg caught in a trap. In describing this panel, Cooke states that the dear is “proved by the character of its horns to be the red deer; an animal now, I believe, nearly extinct in Ireland.” (Cooke p. 278)

2:3 The upper panel contains two images. The lower portion has a horseman who holds a crozier. He sits on a prancing horse with his legs extending forward. Above this image there is a prancing lion with protruding tongue. The tail rises and ends in two leaf-like shapes. Cooke aptly describes the horseman as a bishop. He identifies the bishop as William O’Duffy, a bishop killed by a fall from his horse in 1297. He goes on to suggest that the deer below, because of the Irish word “Davefeei, or Duffy” makes the deer a symbolic image of the bishop’s family name. The fact the deer is caught in a trap is interpreted as pointing to the accident that resulted in the bishop’s death. Based on these conclusions he suggests the cross was carved and set up in memory of the bishop in the late thirteenth century. (Cooke, pp. 278-279)

If Cooke’s assertions are granted that would place the Banagher cross about one hundred years outside the period Harbison sets for the Irish High Crosses. However, based on stylistic features of the art, Harbison suggests a date in the ninth century, about four hundred years prior to the life of Bishop O’Duffy. (Harbison, 1992, pp. 378-379) Harbison’s dating is to be prefered but Cooke’s early explanation is certainly worth noting as part of the history of the interpretation of this particular cross.

Side One:

1:1 The lower panel contains two animals, one atop the other, entangled in a band of interlace. “The tail of the upper animal terminates in a triangular shape in the centre of the panel.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 26)

1:2 The next panel up contains interlace.

1:3 The next panel up contains “Interlinking C-shaped spirals forming pelta-shapes, terminating in two outward-turning spirals at the top.” (Harbison, 19092, p. 26)

1:4 The upper panel has a coiled animal with a fish-like tail. The head is missing.

Side Two:

2:1 A panel of interlace “which terminate in animal-heads with rope-like necks and car-lappets, and with their mouths biting the interlace.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 26)

2:2 This panel is similar to panel 1:3 on side one.

2:3 “Interlace terminating below in animal-heads which bite the interlace. A break groove at the top suggests that a ring may have been inserted secondarily to support the arms of a cross.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 26)

Resources Cited:

Cooke, Thomas L., “The Ancient Cross of Banagher, King’s County”, Transactions of the Kilkenny Archaeological Society, Vol. 2, No. 2 (1853), pp. 277-280.

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Offaly Tourism: http://www.offalytourism.com/businessdirectory/banagher-co-offaly

Clonmacnois

The Site and its History

The Founder: Clonmacnoise was founded by Saint Ciaran, surnamed Mac an Tsair, or "Son of the Carpenter". Ciaran was born at Fuerty, County Roscommon, in 512, and in his early years was committed to the care of a deacon named Justus, who had baptized him, and from whose hands he passed to the school of St. Finnian at Clonard . Here he met all those saintly youths who with himself were afterwards known as the "Twelve Apostles of Erin", and he quickly won their esteem. (newadvent.org; Abbey and School of Clonmacnoise) Photo to the right 2/6/2013 from http://celticvoices.blogspot.com/2010/09/st-ciaran-of-clonmacnoise-sept-9.html

The Founder: Clonmacnoise was founded by Saint Ciaran, surnamed Mac an Tsair, or "Son of the Carpenter". Ciaran was born at Fuerty, County Roscommon, in 512, and in his early years was committed to the care of a deacon named Justus, who had baptized him, and from whose hands he passed to the school of St. Finnian at Clonard . Here he met all those saintly youths who with himself were afterwards known as the "Twelve Apostles of Erin", and he quickly won their esteem. (newadvent.org; Abbey and School of Clonmacnoise) Photo to the right 2/6/2013 from http://celticvoices.blogspot.com/2010/09/st-ciaran-of-clonmacnoise-sept-9.html

After leaving Clonard, Ciaran, like most of the contemporary Irish saints, went to Aran to commune with holy Enda. (newadvent.org; Abbey and School of Clonmacnoise) “Hagiographic accounts suggest specifically that the monastic settlement at Clonmacnoise was inspired by a vision which Saint Ciarán shared with Enda . . . This vision was of a great fruitful tree, beside a stream, in the middle of Ireland protecting the island. Its fruit went forth over the sea that surrounded the island, and the birds of the world came to carry off some of that fruit. Enda advised him that Ciarán was that tree: ‘for thou art great in the eyes of God and men, and all Ireland will be full of thy honour. This island will be protected under the shadow of thy favour, and multitudes will be satisfied with the grace of thy fasting and prayer. Go then, with God’s word, to a bank of a stream, and there found a church’”. (Management Plan p. 57) When Ciaran arrived at Clonmacnoise he was accompanied by seven followers. Only seven months after his arrival, Ciaran died and was succeeded as Abbot by Oenna, one of those followers. (MacGowan, p. 7)

Like many other saints, Ciaran was reported to have a special love for animals. When he went to Clonard to study with St. Finnian, “he took a dun cow and her calf. The cow provided milk for the community. (Earle & Maddox p. 118)

Sources: Textual information about Clonmacnoise comes from the Irish Chronicles and from the Saints Lives. Because the chronicles are generally accepted as reliable only from the late 6th century, the exact date of the founding of Clonmacnoise is uncertain. In all probability Ciaran founded his monastery between 544 and 548 CE.

Location: The selection of the site for Clonmacnoise contributed to its success. Clonmacnoise was built at the strategic intersection of the River Shannon and the Sli Mhor (Great Road). The River Shannon is the longest river in Ireland and runs north/south. The Sli Mhor is an esker that crosses the Irish midlands east/west. An esker is a long narrow ridge composed of sediment laid down by a glacial tunnel. Around the site, making it almost an island are the Shannon Callows (a river meadow submerged during flooding), the Mongan Bog and the River Shannon. It was also sited on the boundary between the kingdoms of Connacht and Mide or Meath.

Layout of the Site: In addition to the importance of the location of Clonmacnoise, the layout of the site as it developed over time has symbolic importance. Archeological surveys have identified three concentric enclosures at Clonmacnoise. “The symbolic significance of this layout is explained in the early eighth-century Collectio Canonum Hibernensis:

‘There ought to be two or three termini around a holy place: the first in which we allow no one at all to enter except priests, because laymen do not come near it, nor women unless they are clerics; the second, into the streets the crowds of common people, not much given to wickedness, we allow to enter; the third, in which men who have been guilty of homicide, adulterers and prostitutes, with permission and according to custom, we do not prevent form going within. Whence they are called, the first sanctissimus, the second sanctior, the third sanctus, bearing honour according to their differences’ ” (Management Plan p. 14)

The photo below shows the present buildings that are within the sanctissimus. (Photo from http://www.planetware.com/map/clonmacnoise-map-irl-clonmac.htm)

The arial photo below puts the image above in context. (Photo from http://sobreirlanda.com/2009/06/03/clonmacnoise-los-inicios-del-cristianismo-en-irlanda/)

The Wooden Bridge: The inhabitants of Clonmacnoise not only built a monastic city, they also constructed a wooden bridge across the River Shannon. This bridge, downstream of the Old Graveyard has been dated to c. 804. It is the oldest known bridge in Ireland. Its span was at least 120 m and it may have stood to a height of 10-13 m. (Management Plan p. 16)

Occupation History: Archeological research has identified three principal phases of occupation. “The uppermost strata, largely disturbed by post-medieval agriculture, are of the late 11th and 12th centuries and are characterised by flagged and cobbled areas, pits, wellshafts and postholes. Below this level is the main occupation phase, dating to the 9th/10th century, with a series of houses and other structures. There is also an earlier phase dating to the 7th/8th century with stake-holes and spreads of burnt soil which indicate quite extensive occupation across the site by the late 8th century. Post-excavation work in ongoing, but it is clear that a period of great expansion occurred in the 7th/8th century with a further reorganisation and new features suggestive of urbanization appearing in the 9th century. (Management Plan p. 18)

Clonmacnoise benefited from royal patronage. This resulted in large grants of land and support for artistic endeavours such as the carving of the High Crosses of Clonmacnoise. Indeed as the wealth, influence and population of Clonmacnoise increased, there is evidence for a wide range of craft activities including work in iron, bone, stone, bronze/copper-alloy, glass, silver and possibly gold. The area was conducive to farming and there is also ample evidence for cereal production. (Management Plan p. 61)

In the early centuries all buildings were constructed of wood or wattle. The earliest of the present stone buildings Temple Doulin dates from the 9th century. The Cathedral dates from the 10th century though it was altered or restored numerous times. Most of the other buildings were built in the 11th and 12th centuries. The three High Crosses are relatively early. The South Cross dates from the 8th century; the North Cross from the 9th and the Cross of the Scriptures from the early 10th.

“In the later ninth and early tenth centuries, the patronage of the Clann Cholmáin of Mide, first under Mael Schnaill, and then under his son, Flann Sinna saw not just the renewal of the monastic core of monumental buildings in stone, with the erection of the stone crosses, but also a burst of chronicling and learned activity in the scriptorium." (Management Plan p. 61)

“The twelfth century is sometimes portrayed as one of decline for Clonmacnoise, but although the arrival of the Anglo-Normans was to prove disastrous, the material evidence of flourishing Romanesque construction suggests, prior to the invasion, an optimistic, well-endowed foundation, benefiting from Connacht and Mide patronage. The round tower was built in 1124 from locally quarried limestone sourced from the Rocks of Clorhane, while in 1167 the Nuns' Church, a key example of the Hiberno-Romanesque style was completed." (Management Plan p. 63)

Following the arrival of the Anglo-Normans and church reform that followed, Clonmacnoise became less significant. It was made the see of a bishop, but of a small and poor see. The population center moved north to Athlone, a less difficult crossing point on the River Shannon. (Management Plan p. 63)

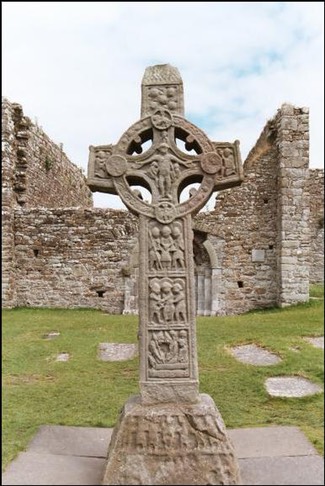

The Scripture Cross

The Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois is one of the outstanding Irish High crosses. It was carved and erected by Abbot Colman in honor of King Flann, who died in 914 CE. We know this from an inscription on the cross itself. The Scripture Cross is a prime example of a genre of crosses that depict biblical scenes, the scripture crosses.

The cross stands 10’4” (3.15m) tall and is 4’9” (1.45m) across the arms. The shaft is 21” (54cm) by 15” (38cm). The base is 29.5” (75cm) tall and measures 47” (1.2m) by 42” (1.07m) at ground level.

In the photo to the left we are looking east and see the cathedral in the background. Begun in 909, the ruins are mostly 12th century.

Base: [photos below, photo to the right from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 139] The base is divided into two panels. The carving is badly damaged. The lower panel has been interpreted as having three scenes, though they are not divided into discrete panels. On the left a possible interpretation is Christ Entering Jerusalem. In the center a possible interpretation is the Resurrection. There are three figures and the one in the middle seems to have arms outstretched. The right side of this panel may show the Holy Women at the tomb. This may show two women approaching the tomb and the angel seated on the stone bearing a cross-shaft. (Harbison, pp. 50-51)

The upper panel of the base shows either the Raised Christ or the Mission to the Apostles. Christ is seated in the center and three apostles approach him on each side.

Taken together the base may represent the beginning of Holy Week with Jesus entering Jerusalem, the women at the tomb symbolizing Jesus’ death and burial with the Resurrection in the center. Above this we may then have the Risen Christ offering the scriptures to his Apostles as in Mt. 28:18-20, a passage known as the Great Commission.

W 1: At the bottom of the shaft we have this scene [to the right] that represents the burial and impending resurrection of Jesus as recorded in Matthew 27:57-28:5. The scene depicts dynamic action. Jesus body is in the tomb. The two guards are leaning together “like dead men.” In the upper right we see the faces of “Mary Magdalene and the other Mary.” The angel appears center right. The small figure in the fold of the angel’s wing may, according to Peter Harbison represent Adam. This is most likely if Jesus’ decent into Hell is part of the testimony of this side of the cross. (Harbison 1992, 51)

W 1: At the bottom of the shaft we have this scene [to the right] that represents the burial and impending resurrection of Jesus as recorded in Matthew 27:57-28:5. The scene depicts dynamic action. Jesus body is in the tomb. The two guards are leaning together “like dead men.” In the upper right we see the faces of “Mary Magdalene and the other Mary.” The angel appears center right. The small figure in the fold of the angel’s wing may, according to Peter Harbison represent Adam. This is most likely if Jesus’ decent into Hell is part of the testimony of this side of the cross. (Harbison 1992, 51)

Most interestingly, there is a bird just above Jesus’ head lower left. It appears to have its beak in Jesus mouth. This could represent the Holy Spirit about to breath life back into Jesus. What we see here may represent the last moment before the resurrection.

This panel reminds us of the difficulty of interpretation of the biblical scenes on the crosses. Some are very clear while others are more obtuse.

W 2: Moving up the shaft, this scene is generally recognized as either the arrest or flagellation of Jesus. Two soldiers are seen to hold Jesus. As in the previous scene, the apparent halos on the two flanking soldiers are interpreted as helmets, though the halo above Jesus’ head is identical and interpreted as a halo.

While the carving of the panel has been worn by wind and water Peter Harbison is able to identify a rod-like instrument in the right hand of the left soldier. This leads him to identify this as the flagellation or beating of Jesus rather than the arrest. (Harbison 1992, 51.)

W 3: Scholars differ on the interpretation of the top scene [to the right]. The key issue is the identification of the center figure. If understood as Jesus, the scene might be Christ on the way to the cross, his arrest, mocking, betrayal or flagellation.

Peter Harbison identifies all three figures as soldiers. Those on the right and left hold spears. The center figure seems to hold a shirt-and a knife. Based on this Harbison interprets the scene as the soldiers preparing to divide Jesus’ garments as in Matthew 27:35. In this act the artist may be referring the viewer to Psalm 22:18 where the belongings of a man desperately ill are already being divided by those around him. (Harbison 1992, 51)

In the panel below the cap, are five interlinked bosses. The curving lines that connect them are typical of what is known as Insular Art, the early art of what is often referred to as the British Isles.

The Ring: Moving down the cross face and focusing on the ring of the cross [to the left] we see it has roundels at 3, 6, 9 and 12 o’clock. The carving on the roundel at 12 o’clock appears to be a horseman.. The significance of this symbol is not known. That at 6 o’clock can be interpreted as a descending dove. Here the symbolism is probably of the Holy Spirit. Its placement below Jesus it could represent his descent into Hell following his death (one possible interpretation of Ephesians 4:9-10.)

In the ring, lower left and upper right we have animal interlace, though it is difficult to decipher in this photo. Upper left and lower right we have bosses linked in S-shapes which tie in with the upper panel above.

The center of the cross head features the crucifixion of Jesus. Peter Harbison writes “Christ, represented as if wearing a short trouser-like garment and with his legs bound, is shown with his outstretched arms falling at an angle and with his large hands bearing the nail heads in the centre of the palms.” (Harbison 1992, 52)

There are other interesting features in this scene. The figures to the left and right of Jesus are traditionally identified as Stephaton (left), who offers Jesus vinegar on a pole and Longinus (right) who stabs Jesus with a lance. Stephaton and Longinus appear in the passion story in the Gospel of John 19:28-34.

There is also a small figure just above Jesus’ head. It is often identified as an angel. It probably symbolizes the presence of God with Jesus as he suffers on the cross.

On each arm of the cross [see photos above] a figure kneels, holding an object. The objects are identified as symbols of the Sun or Ocean on the left or north and the Moon or Earth on the south or right. According to Peter Harbison, during the first millennium, these were symbols used frequently in depictions of the crucifixion . (Harbison 1992, 52)

The top or cap of the cross [to the right] is in the shape of a gable roof with shingles. This is one of the common conventions used for the tops of the Irish High Crosses.

South Side

The base of the cross is divided into two panels. The lower panel contains a hunt scene. From right to left there are two human figures behind two hunting dogs. They seem to be hunting two deer. The photo to the left above is borrowed from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 137. The other photos of the South side are photos of the original Scripture Cross that is housed in the museum at Clonmacnois. The crosses outside are copies of the originals.

The upper panel has been interpreted by Harbison as the Kiss of Judas. On the right Judas embraces Jesus. To the left are four figures bearing staves, presumably those prepared to arrest Jesus.

The shaft contains a plinth and three panels. The plinth contains inhabited vine-scroll. There are "two quadrupeds facing one another and with their heads facing outwards. (Harbison, 1992, p. 50) The plinth is not pictured.

S 1: There are two “X” shaped interlace patterns. Each contains human interlace with a head in each corner of each “X”. See the photo to the right.

S 2: Harbison identifies the panel as David Playing His Lyre. (Harbison, 1992, p. 50) See the photo to the left.

S 3: This panel has been identified in a number of ways. Harbison identifies it as David As Shepherd. It has also been identified as St. Patrick with his angel, and St. John the Evangelist with is symbol the eagle. The central figure holds a crook. Above his head is an angel with outspread wings. See the photo to the right.

The underside of the ring shows us two coiled serpents enclosing two human heads. See the photo to the right.

The underside of the arm contains an image of the Hand of God.

The End of the Arm has a boss with fret-pattern. (Not shown)

The Upper side of the ring and the top of the shaft both have interlace. On the top of the shaft there is also a panel of inerlinked bosses. (Not shown) (Harbison, 1992, p. 50)

East Face

In the photo to the left, we are looking west toward the modern visitor center and museum. The originals of the Clonmacnois High Crosses are located there. The cross in the photo is a replica placed in the location of the original. The photos below, with one obvious exception, were taken of the original cross.

Having a High Cross of quality was a clear sign of the wealth of a monastery. The creation of these crosses in the early years may have been in response to Viking raids. While smaller silver or gold crosses and other fixtures were easily removed, the High Crosses had no value to the Vikings and were not easily movable at any rate.

Clonmacnois was plundered five times in the 9th century, once by the King of Cashel. During the 10th century the monastery was plundered at least nine more times. (MacGowan, 7-9) Given this history it is amazing that the two primary High Crosses were not damaged and that the monastery continued to flourish for 1000 years.

The Base: The base is divided into two panels. The lower panel shows two chariots with large wheels drawn by two horses each. They move from left to right. Each chariot has a charioteer and a passenger.

The upper panel has been interpreted as horsemen. Three men on horseback move from right to left. Porter interpreted this as the Magi on horses while Henry suggested it might represent the Bringing of the Faith to Ireland. (Harbison, 1992, p. 48)

The photo below left is from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 132 while that to the right was taken by the author.

E 1: This scene has various interpretations, some contemporaneous with the cross and others biblical. Harbison sees the possibility that this scene is related to the one above it. Though there are some difficulties with the interpretation he sees this as a possible image of Joseph interpreting the dream of the butler in the text from above found in Genesis 40. The butler says to Joseph, “in my dream there was a vine before me, and on the vine there were three branches. As soon as it budded, its blossoms came out and the clusters ripened into grapes.” (Harbison 1992, 203)

An appealing contemporary interpretation sees the figures as Stain Kieran on the left and King Diarmuid founding the monastery. Diarmait mac Cerbaill was High King at Tara when Clonmacnois was founded.

E 2: In this scene [to the left] we have two figures, both clearly secular as they wear swords. The scene has been given a variety of interpretations that reflect the history of the area from the foundation of the monastery there to the time of the erection of the cross. For example, “conclusion of a pact between Flann Sinna and Cathal mac Conchobair, king of Connacht.” (Harbison 1992, 49) Flann was high king at Tara during the time of the erection of the Scripture Cross.

Harbison offers another tentative suggestion. Keeping with the biblical nature of most of the images he suggests this is an image of the chief butler of Pharaoh offering a drinking horn to him. This would make the image a reflection on one part of the Joseph cycle in Genesis 40.(See also the next figure below.) The butler had been thrown into prison by Pharaoh. Joseph interpreted a dream the butler had and predicted his reinstatement. Three days later he was in fact reinstated. His handing Pharaoh the drinking horn signifies the fulfillment of Joseph’s prophesy. (Harbison 1992, 204) (See also Reflection on the Iconographic Program below.)

E 3: The interpretations of this scene [to the right] are varied. They include the Arrest of Jesus [Mt. 26:47f; Mk. 14:53f; Lk. 22:66f; Jn 18:12f], the Mission to the Apostles [Mt. 10:1f; Mk. 6:6f; Lk. 9:1f], and the story of the Loaves and Fishes [Mt. 14:13f; Mk. 6:30f; Lk. 9:10f; Jn. 6:1f].

From time to time a scene on a Scripture Cross will be given a contemporary (10th century) meaning. One interpretation of this scene is Odo rebuilding the church of Saint Kieran.

Harbison, who reports the interpretations above identifies this as the Traditio Clavium or Giving of the Keys. In Matthew’s version, Jesus says to Peter “I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.” [Mt. 16:19] He identifies the third figure as Saint John. In the scene Jesus gives him a book (the gospels). (Harbison 1992, 49)

The Head: The center of the head of the cross and the arms form one integrated scene. This is clearly the Last Judgment. Harbison writes: “Christ stands . . . carrying a scepter . . . over his right shoulder and a cross-staff over his left shoulder. To the left is a figure . . . playing a flute, behind which . . . are the righteous turning toward Christ. To the right of Christ . . . is a figure with its back to Christ and holding what may be a three-pronged fork over the right shoulder, driving further to the right the wicked who have turned their backs on Christ on their way to eternal damnation.” (Harbison 1992, 49)

This image is a composite, not related to any specific biblical text. There may be some relation to the Judgment of the Nations in Matthew 25:31ff. Another possible connection may be with story of the Messages of the Three Angels in Revelation 14:6ff. Mostly it reflects an image the early church had come to associate with the Last Judgment.

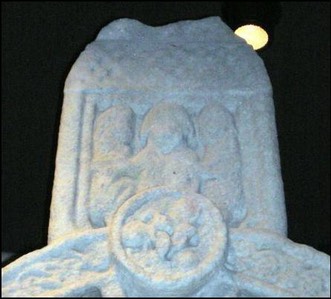

Top Panel: Scholars do not all agree on the identification of the scene at the top of the east face of the cross.

Harbison identifies it as the Majestas Domini or the Majesty of the Lord. He identifies the central figure as Christ and the two flanking figures as angels. While not evident in this photo, Christ is holding a book. (Harbison 1992, 49)

Veelenturf tells us that the Majestas Domini image, is absent from the Irish High Crosses. Missing from the Scripture Cross image are the technical characteristics of Christ offering a blessing and Christ surrounded by four beings symbolizing the four Evangelists: Matthew as a man, Mark a lion, Luke a calf and John an eagle. (Veelenturf, 32, 68)

In either event, Christ and the Gospels are represented in the image [above], perhaps Christ as Risen Lord.

Reflection on the Iconographic Program: It may be possible, in some cases, to read the images on a scripture cross as representing one iconographic whole. It has been suggested that the theme of the west face of the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois is the Passion Week. Theologically this is the pivotal event in God’s action for salvation. We have, from top down, the crucifixion, the soldiers dividing Jesus' garments, the arrest or flagellation and at the bottom Jesus in the tomb.

It is possible to read the east face of the Scripture Cross as continuing the theme of salvation. Reading from the top down, we have the Risen Christ, the agent of salvation; Christ and the Last Judgment, with some saved and some cast out; the Church in the persons of Peter and John being given the keys to the kingdom and the gospels, the temporal power of salvation; and, seeing Joseph as prefiguring Christ, God’s historic and ongoing work for salvation. This latter is related to the Last Judgment in that while Pharaoh’s baker is not shown in the lower two panels, those knowing the story would know that while the cup-bearer was restored, the baker was beheaded. In addition, both panels have to do with the events that led to the release of Joseph from prison and his eventual rise to power in Egypt under Pharaoh. It is significant that Joseph’s interpretation of the butler’s dream was fulfilled on the third day, even as Jesus was raised on the third day.

North Side

The Base is divided into two panels. The lower panel contains three animals moving to the right and apparently being driven by a person to the extreme left. Harbison identifies the animal directly in front of the man as a possible unicorn. (Harbison, 1992, p. 52)

The upper panel contains three animals moving left, at least two of which are griffins. Between them is what appears to be a human head and neck. The central animal seems to be atop a human body lying along the bottom of the panel. The right hand animal may be a lion, possibly with a human leg in its mouth. See the photo to the left, from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 145.

The Plinth is not clear in the photo to the right. Harbison describes it as “containing two quadrupeds with necks contorted in such a way that their heads look sideways toward the observer. They are enmeshed in interlace, which may emanate from a tree centrally placed between the two animals.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 52) See the photo to the right.

N 1: This panel is subject to a wide variety of interpretations. Harbison thinks it may represent St. Anthony overcoming the devil, depicted in human form. Other interpretations include: The Triumph of learning over ignorance, Christ spearing Satan, St. Patrick subduing the devil and St. Michael defeating the devil. (Harbison, 1992, p. 52)

The central figure is seated and with his right hand stabs a staff into the eye of a figure lying on its back below with legs pointing upward. Atop the staff is what appears to be a bird. In his left hand the central figure holds something that could be a book.

N 2: This figure has also been interpreted in many ways. Harbison suggests it may represent the burial of St. Paul the Hermit. Others have suggested that a wandering ministrel is visiting King Flann or the enchantment of the Sidhe playing music. The two animals at the bottom have been identified by some as representing Lust. (Harbison, 1992, p. 53)

The central figure is playing a piped instrument. Left of his head Harbison suggests a catlike creature. At the bottom of the panel are two lions, each facing away from the center. Harbison suggests that “As the lions may be those which made their appearance to help dig the grave of St. Paul the hermit, the figure may represent St. Anthony playing a lament for his deceased fellow.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 53)

N 3: Consistent with his description of the lower two panels as relating to St. Anthony and St. Paul, Harbison suggests this panel depicts the two saints together.

The scene seems to contain a seated figure holding a tau crozier before him. There is a round figure on his chest that could represent a brooch or possibly the eucharist. Above and behind this figure is another figure that seems to hold a lock of the lower figures hair in his left hand and something that could be a book in his left. Because the crozier is a tau cross on top, Harbison tentatively identifies the central figure as St. Paul. (Harbison, 1992, p. 53)

The underside of the ring contains two heads enclosed in the coiling of a serpent.

The underside of the arm contains a cat-like figure probably devouring a mouse. See the photo to the left.

The end of the arm is much worn, but according to Harbison it contains a boss and a central panel with a cross-shape that divides it into nine panels. Each bears decoration, but the pattern is unclear. (Harbison, 1992, p. 53) See the photo to the right.

The upper side of the arm has interlace.

The top of the shaft contains “A panel of bosses against a fretwork background, and with interlace above it.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 53)

The North Cross

The presence of a base and lower shaft, exposed in the 1950s indicated this was indeed a cross. Carving on the lower shaft and the base is unclear at best. (Bourke, p. 116) The shaft stands 73” (1.85m) tall and measures 15” (39cm) by 12.5” (32cm). The photo below right shows the south side of the cross shaft as a guide interprets it.

South side:

S 1: Animal interlace.

S 2: A figure facing forward with crossed legs.

S 3: Three snakes interlocked.

S 4: An animal in profile, identified by Harrison as a lion.

East face:

This side of the shaft is undecorated.

West face:

W 1: Interlace of encircled shapes.

W 2: “Four animals with coiled bodies and extended nicks, the necks and bodies interlocking and two legs perhaps projecting in opposite directions from the centre of each coil.” Bourke, p. 116)

W 3: Interlace that Bourke suggests this may be four snakes with heads in the four corners. (Bourke, p. 116)

W 4: “Interlace with fish-tail terminals forming four loose spiral-shaped designs set around a small ring in the centre.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 54)

W 5: Harbison also describes a partial upper panel that contains a cross-shaped figure with circular interlace. (Harbison, 1992, p. 54)

The photo below shows from left to right the North, West and South sides of the cross. The source of the photo is Bourke, unnumbered page.

North side:N 1: Interlace

N 2: Interlaced animals

N 3: This is a complicated panel that contains three parts. Below I quote Harbison’s description.N 3 a: “In the lowermost section there is a quadruped with raised left hind leg. It turns its head backwards to bite the hind leg of the animal forming the middle section above it.”

N 3 b: The lower figure in the middle section of the panel seems to place “its right hind leg on the hindquarters of the lower animal, as it turns its head back to bite what seems to be its now tail. The second, upper animal may have its front leg raised in front of it.”

N 3 c: “The uppermost section of the panel shows a now headless but probably human body decorated with spiral ornament, with its right leg folding beneath itself, the anatomically curious left leg starting above the right leg and then interlacing with it at a diagonal. Curled up at the bottom of this upper most section of the panel is an animal which coils its serpent-like body in a broad sweep above the human figure’s left lower leg and underneath its right ankle, then above the right upper leg and beneath the left upper leg, and finally running out or expanding to the right of the spiral-decorated human body.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 54) (See the illustration to the right: Source, Bourke, p. 118)

Notes from Cormac Bourke

Bourke focuses in his article on the upper panel on the north side of the cross (N 3 c). He suggests this human figure conforms to a recognized type that appears in both Pictish art and in the Book of Kells, and he offers several examples including the left tympanum on folio 5r which is illustrated below. (Bourke, unnumbered page)

Bourke states that Henderson “has defined three styles used in the portrayal of human figure which she suggests are common to Pictish art and the art of the Book of Kells. The Clonmacnois figure belongs to the second or ‘decorative repertoire of interlace spiral or key, or is combined with an animal to make a decorative design.’” (Bourke, p. 119)

Bourke also calls attention to the similarity of “motifs carved in low and flat relief” of the North Cross at Clonmacnois, the shafts from Banagher and Roscrea and the cross at Bealin. Based on an inscription on the Bealin cross, a date around 800 has been suggested for the carving of this group of crosses. (Bourke, p. 116)

The South Cross

As the name implies, the South Cross is located south of the Scripture Cross near the south-west corner of Temple Doolin. (See the site diagram above.) It is a sandstone cross that stands 9’6” (2.9m) and has an arm span of 46” (1.16m) The shaft measures 18” (46cm) by 11.5” (29cm) at the base. The base is 33.5” (85cm) tall, and measures 46.5” (1.18cm) by 33.5” (85cm) at ground level. The photo to the left is the original cross, located in the visitor center. The east face is shown. The description below follows Harbison. (Harbison, 1992, pp. 54-56)

East Face:

Base: The base has three horizontal panels. The lowest panel depicts at least five horsemen moving to the left. It may also include a lion. The middle panel contains interlace. The top panel probably contains interlace but is badly worn. See the photo to the right, the images are very faint.

Shaft: The plinth has what Harbison refers to as “debased fret pattern.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 54)

E 1: Inhabited vine-scroll with birds and quadrupeds.

E 2: Bosses with interlace joined by trumpet-patterns.

Head: The background is fret pattern. From this five bosses are in relief, each with interlace. The center and upper bosses have interlace arranged in a way that a cross appears in the center of each.

Ring: There is animal ornament in the ring that combines interlace and animal interlace.

South Side:

The photo to the right is from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 155. The description below follows Harbison p. 55.

Base: The base is badly worn but Harbison was able to discern two vertical panels on the lower part of the base. That on the left has an image of Adam and Eve, the tree and the serpent. On the right Harbison identified the Sacrifice of Isaac. This is a very uncertain identification.

The middle panel on the base contains interlace in what appear to be circular patterns. The upper panel seems to have knots of interlace.

Shaft:

Plinth: interlace

S 1: Four bosses aligned vertically and linked with spiral patterns.

S 2: Interlace

Head:

Underside of ring: It is divided in two by a vertical rib. On the left is fretwork and on the right interlace.

End of Arm: “The end of the arm has two linked interlaces of disparate size, framed together by a raised hatched moulding.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 55)

Top of ring: Like the underside of the ring it is divided by a vertical rib with interlace on the left and fretwork on the right.

Top of shaft: A panel of fretwork.

West Face:

Base: The lower panel on this face is divided into three vertical sections divided by ribs. In the center is a bossed decoration, on each side is a panel of interlace in circular design.

Middle: This panel shows a hunting scene with a man on the right carrying a stick and chasing birds and quadrupeds toward the left. One of these is a deer.

Upper: The decoration here is unclear.

Shaft:

Plinth: no decoration now visible.

W 1: “An interlace, possibly of animal type, forming four spiral devices.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 55)

W 2: Interlace that forms nine circular devices.

W 3: The Crucifixion scene with Stephaton and Longinus. Above the arms of the cross there is a figure on each side that may be intended to represent the Moon or Ocean on the left and the Sun or Earth on the right. See the photo to the right.

Head: Five bosses decorated with interlace are in relief while the background is decorated with pelta-shaped patterns.

Ring: There are raised mouldings, but any decoration that was there is not discernable.

North Side: The photo below is from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, figs. 159-160.

Base: The lower section is divided into two vertical panels. Any design that was there is no longer visible.

Middle: “Four squares of cross-shaped fretwork.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 56)

Upper: Interlace making five spiral devices.

Shaft:

Plinth: “The plinth bears two pairs of pelta-shaped forms, one on top of the other, and back to back.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 56)

N 1: Animal interlace

N 2: Interlace patterns interlocked and forming a rough circle.

Head:

Underside of ring: As on the south side a rib separates the ring into two panels with fretwork on the right and interlace on the left.

End of the Arm: Interlace inside hatched rope-moulding.

Upper side of ring: Like the underside a rib separates two panels. The one on the right contains interlace.

Top: An interlace pattern.

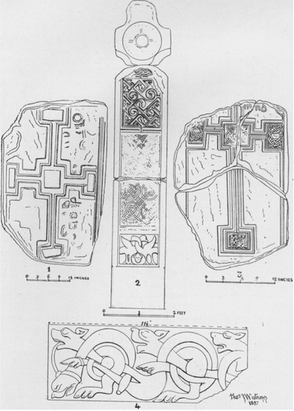

Upper Part of a Shaft:

This fragment of a sandstone cross was found by Liam de Paor in 1955. It was buried in the wall of St. Ciaran’s church. It is just short of two feet in height. The photos below are from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, figs. 161-164.

East Side: vertical interlace, see photo far left.

North Face: Interlace, see photo second from the left.

West Side: Interlaced Stafford knots, see photo second from the right.

South Face: “Two upright lions with interlocking jaws facing one another.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 56) See photo to the far right.

DU018-191—-There is a cross fragment (OF009-005006-) mentioned just above at Clonmacnoise, Co. Offaly (OF990-005009) and this piece appears to have come from the shaft of a high cross: It has interlace decoration. The missing cross head described below and the possible fragment of the shaft may belong to the same cross. This cross-head is now housed in Dublin, in the National Museum of Ireland (IA File, IA/29/1988). The cross-head is on display in the museum.

In 1974 the head of a high cross was removed from the monastery at Durrow and was described by Harbison as "A cross-head of sandstone stood for centuries on top of the gable of the now disused Protestant church to the east of the main cross. It fell to the ground in the late 1950s, after which it was placed on a base just south of the church. In 1974 it was, apparently, removed to Durrow Abbey nearby, in the grounds of which the old monastic site lies. The cross-head is 43cm (17 inches) high, 68cm (27 inches) across the arms, and the lower part of the shaft has a maximum width of about 20cm (8 inches) The arms expand markedly at the terminals, and it seems unlikely that the cross originally had a ring. The ends of the arms are probably not decorated.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 82)

In 1974 the head of a high cross was removed from the monastery at Durrow and was described by Harbison as "A cross-head of sandstone stood for centuries on top of the gable of the now disused Protestant church to the east of the main cross. It fell to the ground in the late 1950s, after which it was placed on a base just south of the church. In 1974 it was, apparently, removed to Durrow Abbey nearby, in the grounds of which the old monastic site lies. The cross-head is 43cm (17 inches) high, 68cm (27 inches) across the arms, and the lower part of the shaft has a maximum width of about 20cm (8 inches) The arms expand markedly at the terminals, and it seems unlikely that the cross originally had a ring. The ends of the arms are probably not decorated.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 82)

East Face: (?) David as Shepherd. "A figure stands with a crook in its left hand, and there may be a sheep with turned-back head to the right. Above the figure’s head there is what is probably an angel, on the analogy of panel S 3 of the Cross of the Scriptures at Clonmacnois. The figure is most likely to represent David as Shepherd, the presence of David in such a position at the centre of the cross-head being rendered quite likely in view of the David interpretation suggested here for the scene at the centre of head of the Tall Cross at Monasterboice. The arms are decorated with interlace.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 83)

West Face: The Crucifixion. "Christ is shown in a tight-fitting garment, stretching his arms out at right angles. Stephaton and Longinus are indicated as busts beneath Christ’s arms, though their attributes are not shown. At the end of the arms there is a whirl from which serpent headed animals emerge. Above Christ’s head, a bird flies upwards to the left." (Harbison, 1992, vol. 1, 82-3)

See this information also under Durrow, Co. Offaly.

Clonmacnois Pillar

This pillar may have been part of a cross, but no mortise or tenon exists to indicate an upper section may have been mounted on top. One side of the pillar is not decorated, suggesting it may have been mounted against a wall.

The photos to left and right are from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, figs. 165-167. The descriptions follow Harbison Vol. 1 p. 57.

East Side: a badly damaged interlace pattern.

South Face: There is one panel with four figures aligned vertically. At the bottom is a lion, its head turned back, he is biting his tail.

Above the lion is a horseman facing to the left.

The third and fourth images are both lions. The lower of the two lions is moving to the right but, like the lion at the bottom its head is turned back and it is biting the right front leg of the lion above it. The lion above is facing right. Both lions have foliate tails.

West Side: a badly damaged interlace pattern.

North Face: undecorated.

Fragments in the National Museum, Dublin

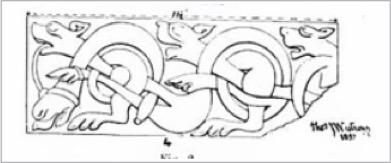

DU018-190—- “Fragments of a possible high cross that originally came from Clonmacnoise, County Offaly (see OF005-064—-). Described by Harbison as ‘In the National Museum in Dublin there are some fitting sandstone fragments from Clonmacnoise. The top of the upper fragment is so damaged that it is difficult to know whether it formed part of a pillar or cross. Together, the fragments measure about 90cm (35 inches) in height, and they are 35cm (14 inches) wide and 18cm (7 inches) thick. Their edges have been damaged, and the panels are framed by a raised moulding. There is a large tenon at the bottom, but no trace of a mortise hole on top. Only one face is decorated suggesting that it may have originally stood against a wall.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 57) In the photo below the left end is the lower end of the shaft.

Main Face: "Three deeply carved pelta motifs one above the other and rising from a double raised moulding below. At each end they roll into a three-coil spiral terminating in pierced lobes. There is a ‘drop’ appended to the centre of the pelta, which is formed of two facing trumpet-ends, above which there is a three pointed interlace.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 57)

Left Side: A panel of interlace. This side was against a wall when I visited it. The photo below is taken from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, fig. 169.

Right Side: "A vertical panel divided into three sections. In the centre there is an interlace. Above and below it there are two sunken crosses surrounded by a stepped raised moulding, outside which there is a further stepped moulding with a square in the outer corners." (Harbison, 1992, vol. 1, 57). The photo below shows this side of the shaft.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 33, C3. Located along the R444 and well sign posted. The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Resources Cited:

Bourke, Cormac, “A Panel on the North Cross at Clonmacnois”, The Journal of the royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 116 (1986), pp. 116-121.

Earle, Mary & Maddox, Sylvia, Holy Companions: Spiritual Practices from the Celtic Saints, Morehouse Publishing, London, 2004.

Harbison, Peter; The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey, Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1

MacGowan, Kenneth, Clonmacnois, KAMAC Publications, Dublin 1998.

The Monastic City of Clonmacnoise and its Cultural Landscape, Management Plan 2009-2014, prepared by The Office of Public Works and Environment, Heritage and Local Government, 2009.

newadvent.org; Abbey and School of Clonmacnoise; Catholic Encyclopedia.

Veelenturf, Kees, 1997. Dia Bratha: Eschatological Theophanies and Irish High Crosses, Stichting Amsterdamse Historische Reeks.

Drumcullin (Knockbarron)

For those interested in a concise but very comprehensive description of the Drumcullen cross-head and the background of the Drumcullen monastery the best read would be a brochure written by Dr. Peter Harbison entitled “The Drumcullen Cross-head of c. 900.” The link to this brochure is below. Here I will offer a brief summary taken from this and the other sources cited.

The Monastery

In an article published in 1918, Olive Purser describes finding the cross-head. She offered a description of both faces and some basic information about the supposed founder of the abbey. (Purser and Armstrong, pp. 74-77)

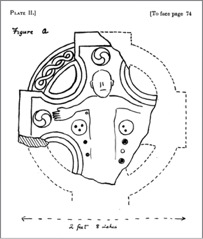

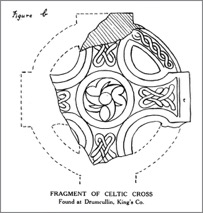

This same article offered drawings of both faces of the cross-head. These are pictured below along with photos and descriptions of the cross-head. (Purser and Armstrong, figs. a and b.)

The photo above shows the ruined church at the site. The cross-head was located in front of the church to the right.

Harbison suggests Drumcullen must have been important in spite of a scarcity of mentions in the annals. It was home to both the cross of which the current cross-head was part and the Kinnitty cross now located at Castlebernard nearby. The Drumcullen monastery is located near the river Camcor which was the ancient boundary between Leinster and Munster. Drumcullen is on the Lenister side of the river while another monastery at Kinnitty, not far from Drumcullen, lies on the Munster side of the Camcor.

In an Ordnance Survey Letter for King’s County we find: “The name of Drumcullen Parish in the Barony of Eglish is in the Irish Calendar written Druim Chuilinn, where we read:- ‘Bairfionn, Bishop from (of) Druim Chuilinn and from (of) Killbarfinn near Eas Ruadh to the north. He was of the race of Conall Gulban who was son of Niall, etc.’” (Ordnance Survey Letter)

The letter goes on to state that in 591 Barrindeus was abbot of Drumcullin and it flourished. Later, the Annals of the Four Masters record for 721 that St. Cuana of Druim Cuilinn died and for 740 that Ceannfaola, Comharb of Druim Cuilinn died. (Ordnance Survey Letter; see also Annals of the Four Masters)

The Saints

Harbison tells us that there were two saints connected with Drumcullen. One was Rioghnach, a female saint. The other was Barinthus, a male saint. Not much is known of Rioghnach. The Martyrology of Donegal tells us she was sister to Finnian of Clonard and mother of Fionntainn, a Priest, of Fochuillich. (O’Donovan, p. 197)

We know only a little more of Barrinthus or Barrindeus. He was Abbot of Druimcuillin and also of Killbarron in Tirconnell, county Donegal. He was of the family of Niall, the most powerful family in the north of Ireland and is mentioned as having encouraged Brendan to undertake his famous voyage. (Walsh, p. 508)

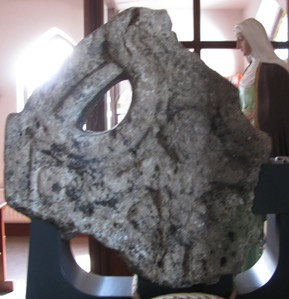

The Cross

The photo to the left was taken in 2008 before the cross-head was moved for preservation from the ruined abbey where it was found. The face showing is described below as the east face.

The descriptions of the carving on the cross are taken from Harbison, 1992, p. 75, except where elsewhere noted.

East Face:

The arms and the ring have interlace decoration. In the center a raised moulding encloses a spiral decoration. The design can be seen clearly in Figure b to the left. (Purser, Fig. b)

South Side:

On the underside of the ring a vertical roll moulding if found. On the end of the arm there is a panel of interlace.

West Face:

In the center of the head is a scene from the crucifixion. The figures of Stephaton and Longinus are suggested to the left and right of Jesus. “There is a hemispherical boss (SOL, the sun, or a worn human head?) at the end of Jesus’ arm.” Above his head is what may be a spiral motif. In Fig. a to the right this spiral motif is copied at the end of Jesus’ right arm.

Writing in the brochure for Drumcullin, Harbison writes, “There are, however, two curious features associated with the Crucifixion figure. The first is a large rounded boss in relief on the arm of the cross beyond Christ’s right hand. there was doubtless a somewhat similar-shaped boss on the other, lost, arm. On possible explanation is that these represented the cosmic symbols, sun and moon, whose faces may well have been painted onto the smooth surface of the boss.” (Harbison, brochure)

The West Face is seen in the photo to the left, the East Face in the photo to the right.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 43 1 D. The cross-head is on public display inside the Rath Roman Catholic Church less than 2 km southeast of the N 52. The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Resources Cited

Annals of the Four Masters, http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/T100005A/index.html

Catholic Ireland, “High Cross Fragment displayed in Meath parishhttp://www.catholicireland.net/ancient-high-cross-fragment-displayed-in-meath-parish/

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Harbison, Peter, “The Drumcullen Cross-Head of c. 900”, www.offaly.ie/eng/Services/Heritage/Archaeology/Monastic_Sites/Drumcullen%20high@20cross%20head%20brochure%20.pdf

O’Donovan, John, The Martyrology of Donegal, A Calendar of the Saints of Ireland, Dublin, 1864.

Ordnance Survey Letters King’s County, Letter no. 32 from Thomas O’Connor, Birr, Jan. 26th 1838: https://www.offalyhistory.com/reading-resources/archaeology/ordnance-survey-letters-for-offaly-in-1838/the-old-church-at-drumcullen

Purser, Olive and Armstrong, E.C.R., “Fragment of a Celtic Cross Found at Drumcullin, King's County” The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Sixth Series, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Jun. 30, 1918), pp. 74-77

Walsh, Thomas, History of the Irish Hierarchy, with the Monasteries of Each County, Biographical Notices of the Irish Saints, Prelates, and Religious, New York, 1854.

Durrow

The Site:

The monastery at Durrow was founded by St. Colum Cille (521-597). It lies along the Eiscir Riada, the major east-west roadway across Ireland. This same ridge crosses the River Shannon south of Durrow where Clonmacnois lies. The early name was Daru or Dairmag. The exact date of founding is unknown though Charles-Edwards suggests it was probably between 585 and 597 (the year Colum Cille died). (Charles-Edwards, p. 555) The point has been debated. Some suggest that Durrow was founded before 563, the date when Colum Cille left Ireland for the Isle of Iona in Scotland. Others believe it was founded after 575, while Colum Cille was back in Ireland for a Synod of Drumkeatt. He appears to have remained in Ireland for an extended time following the Synod and may have founded Durrow then, or on a subsequent trip back to Ireland.

Colum Cille was a member of the Ui Neill family and more specifically the Cenel Conaill, the dominant branch of the Ui Neill at the time Durrow was founded. Charles-Edwards suggests that the founding may have had a political aspect. The Cenel Conaill was at the time seeking to continue the decline in influence of the Cenel Fiachach, a rival faction of the Ui Neill. Durrow lies just about four miles from the chief monastery of the Cenel Fiachach and with royal patronage its foundation would have added to the influence of the Cenel Conaill in that area. (Charles-Edwards, p. 555)

Durrow was a daughter house of the monastery of Iona, the primary Columbian foundation. A number of the most influential monasteries had daughter houses. The daughter houses of Iona included Derry and Durrow, and in the early ninth century Kells, which due to the pressure of Viking attacks on Iona became the new center of the Columbian foundations. (Charles-Edwards, pp. 250 and 587)

The Venerable Bede, an eighth century English monk who wrote “The Ecclesiastical History of the English People” referred to Durrow as a monasterium nobile or famous monastery. It was large both in population and in land area. The present church and graveyard area are only a small part of the larger monastery at its heights.

Durrow experienced challenges over the course of the years. In 764 it found itself at war with the folk of Clonmacnois over issues of political and spiritual influence. The Annals report that 200 of the Durrow men died. The Chronicon Scotorum reports that Durrow was burned in the year 833. In 1019, according to the Annals of Lough Ce, the sanctuary of the church was violated. Molloye, King of Fearceall had sought asylum there and was removed by force and later killed. The Annals of Clonmacnoise place this same event in 1013. In 1095 the books of the library were burned, fortunately the Book of Durrow was not destroyed.

The twelfth century saw the arrival of the Augustinian Canons who opened a house near the old monastery. In 1153 and again in 1155 fire damaged or destroyed the monastery. In 1175 the Normans destroyed the old monastery. While the Augustinians remained, the monastery declined in significance.

We have the names of only a few of the Abbots of Durrow. Cormac Ua Liathain is said to have been appointed Abbot by Colum Cille when he left for Scotland. Abbot Ruadhan also dates to the sixth century and so would have been an early abbot of the foundation. About 630 we know that Cumain was Abbot of Durrow and the Annals of Ulster report that Saergus Mac Cuinnid (Soergus Mac Cionnaoth) the Abbot of Dairmag (Durrow) died.

Little remains of the early monastery. The church presently on the site was build during the renaissance period. The illuminated Gospels known as the Book of Durrow, dating from about 700, is on display at Trinity College, Dublin. The High Cross, that will be described below, dates to the early tenth century, while a smaller cross head, also described below, may be a bit earlier. An eleventh century crozier, venerated as that of Colum Cille, is now in the National Museum of Dublin. There is also a probable cross base, known as the “headache stone” as well as a holy well on the site. In the field to the north and west of the church part of the circular bank and ditch which once protected the monastery can be seen, especially in an aerial photograph.

The Saint:

Much has been written about St. Colum Cille (Columba). Our primary resource is the Vita Columbae or Life of Columba written by Adomnan, Abbot of Iona, about a century after Colum Cille’s death. Colum Cille was born in County Donegal in 521and studied under St. Finnian at Clonard. Finnian's school was noted for sanctity and learning. Colum Cille was one of twelve students of Finnian who became known as the Twelve Apostles of Ireland. As noted above, Colum Cille was a member of the Royal family of the Ui Neill. Indeed when he was born his half uncle was High King at Tara and during his life six of his cousins reigned as High King.

He founded a number of monasteries in Ireland prior to his exile from Ireland in 563. He then founded the monastery at Iona in Scotland. As noted above, he returned for the Synod of Drumkeatt, after which he remained in Ireland for a time and founded other monasteries, possibly including Durrow. He then returned to Iona where he died in 597.

The Crosses

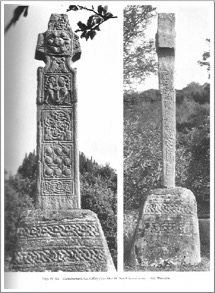

The West Cross at Durrow

Inscriptions: There are two inscriptions on the plinth of the shaft of this cross. One is on the west face, the other on the north side. Both of these inscriptions have been damaged, likely “the result of deliberate action and the use of stone working tools, chisels and punches.” O Murchadha, p. 55) O Murchadha and O Murchu did an extensive analysis of these inscriptions, publishing their results in 1988. They propose the most complete reading of this inscription yet ventured, but they offer no translation of the text.

The inscription on the north side of the cross might be rendered as follows: (O Murchadham p. 58)

O R D O [M] _ _

S E C H N A _ _ _

R I G H E R E _ _

O R _ O C _ O _ _

A _ D O R R O _ _

A C H R O _ S

The first line probably said “prayer for”, a typical part of an inscription. The second line may provide the name of Soergus Mac Cionnaoth, abbot of Durrow till his death in 835/6. The next lines would then ask a “prayer for” and provide the name of the person who erected the cross. (Harbison, 1992, p. 359) A few years later, Harbison wrote: the inscription “on the north side, though poorly preserved, can reasonably be reconstructed to include the name of king Maelsechnaill — leaving the options open as to whether it was commissioned by him or was commemorating the achievements of a dead man.” (Harbison, 1998, p. 165) If the Maelsechnaill referred to is Mael Sechnaill mac Mail Ruanaid, king of Mede (Meath) from 845-862, and if we have the correct Soergus, it is possible that the king caused the cross to be raised to honor the late abbot, and of course, himself.

The inscription on the west face of the cross is more badly damaged than that on the north. About all that can be safely postulated is that the inscription begins with “prayer for”. Suggestions for a name in the inscription, made by Stokes and Smyth include Dubhthach, Airchinnech of Durrow who died in 1010 and Dubtach who was head of the Columbian monasteries of Ireland from 927 to 938. (Harbison, 1992, p. 358) Either of these identifications would place this person long after the death of Soergus and Maelschnaill.

The West cross at Durrow can be roughly dated to the “second and third quarters of the ninth century, and the . . . first half of the tenth.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 368)

The descriptions below are based on the work of Harbison (1992, Vol. 1, pp. 79-83)

East Face:

Base: There are two undecorated panels on the base.

Plinth: Any identification is uncertain. There may be a ringed cross or the head of a lamb with a ringed head to the left. The center may contain a human figure with an animal or two centaurs face to face.

E 1: The Raised Christ. This image has a central Christ figure with an angel on each side of the head. His feet are on the knees of two robed figures seated opposite each other. They have an open book between them. They probably represent Peter and Paul and the book the gospel.

E 2: A panel of interlace with circular devices.

E 3: The Sacrifice of Isaac. Abraham is on the left with a sword in one hand and the fire in the other. Isaac is on the right, one knee on the ground. He holds an ax and carries the wood for the sacrificial fire. Above him are an angel and the ram.

Center of Head: The Last Judgment. A central Christ figure holds a cross-staff and a scepter. Above his head is a lamb in a circle. He stands on interlace that may represent clouds. On the left and right are angels. One with folded hands, the other blowing a pipe.

South Arm: David Playing the Lyre. The very end of the arm contains interlace.

North Arm: David Slays the Lion. David, knee on the back of the lion, pulls apart its jaws. In front of him is a lamb.

Top of Head: A square panel has bosses in each corner. From these emerge animals which bite one another in the center and others with heads on the outer periphery of the bosses.

The Ring: There is roll moulding framing animal interlace in the lower left and upper right segments. There is fretwork with spiral terminations in the lower right segment. The upper left segment decoration is unclear. Inside the ring are cylinders with round bosses on the ends.

South Face:

Base: The base has one undecorated panel.

Plinth: While difficult to see in the photo, there are two winged animals standing opposite one another under a tree. The animal on the right appears to grasp the tree.

S 1: Eve Gives the Apple to Adam. Once again we have a tree, this one with spiraling branches. The serpent is not prominent. Eve is on the left handing a fruit to Adam.

S 2: Cain Slays Abel: Cain appears on the left in profile. He strikes his brother Abel with a club. Abel is on the right and appears in a frontal position.

S 3: David as King: David is seated and holds a sword and a shield. There are two animals, one on each side, both having their heads in David’s lap.

Underside of Ring: In a center panel a snake coils around three human heads. To the left is a panel of S-spirals, while to the right are C-shaped spirals.

End of Arm: The end of the arm is shaped as a truncated pyramid. On a panel on the truncated end is a panel of fretwork.

Upper side of Ring: Probable interlace on the left.

Top: A horseman moves to the left. Above this is a triangular panel that is too worn to identify.

West Face:

Base: There are two undecorated panels.

Plinth: There is an inscription that is described above.

W 1: Christ in the Tomb: Jesus’ body lies below a grave slab, his head uncovered by the slab. Above two soldiers lean together, each holding a spear. There may be a small human figure between them. On the left a small bird stretches its beak toward Jesus’ head.

W 2: The Mocking or Flagellation of Christ. The figure of Jesus is in the center, facing left. He appears to be held by a solder behind him who also faces left. In front of Jesus a second soldier holds a flail in each hand. With one he appears to beat Jesus on the shoulder.

W 3: The Soldiers Casting Lots for Christ’s Garments. The three figures are interpreted as soldiers. The one in the center appears to hold Jesus’ garment. The soldiers on each side hold swords and face toward the central figure.

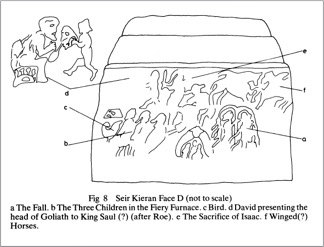

Center of Head: The Crucifixion. Jesus is in the center, his feet on interlace, his feet tied, his arms outstretched. On his left Stephaton offers him vinegar while on the right Stephaton pierces his armpit. Above Jesus’ head a bird, probably representing the Holy Spirit perches on his head with outstretched wings.