This page highlights the crosses of County Clare. These include Dysert O’Dea Cross in the Field and Cross in the graveyard, Inis Cealtra, Kells, Kilfenora, Killaloe, Killnaboy, Kilvoydan, Noughaval, and Skeaghavannoe. County Clare is located with a star on the map to the right.

Historical Background of County Clare

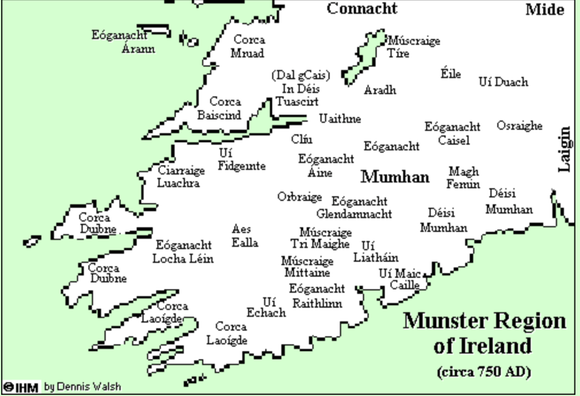

In the twelfth century, Thomond was the designation of a geographic area that included County Clare, County Limerick and part of County Tipperary. From the eighth century it was the home of the Corco Baiscind in southern Clare; the Corco Mo-Druad in northern Clare, the Desi Tuaiscirt in eastern Clare and Limerick and other smaller clans or tribes. Thomond was, in turn, part of the larger kingdom of Munster.

Ancient divisions of Munster listed in the Irish annals included:

Érna Muman, or Ernaibh Muman - ancient land of the Ernai tribe.

Desmhuman, or Desmumu - Desmond, or south Munster.

Tuadhmhuman - Thomond, or north Munster.

Urhmumhan, or Urmumu - Ormond, or east Munster.

Iarmumhan - west Munster.

Deissi Muman - Deisi, or the County Waterford area.

(http://what-when-how.com/medieval-ireland/dal-cais-medieval-ireland/)

During the period of 400-800 CE, the Corcu Mo-Druad were dominant in the area of the Burren in northern what is now northern Clare; the Corcu Baiscind were dominant in southern Clare. Both of these tribes were under the influence of the Eoganacht, the leading tribal group at this time in Munster. The Eoganacht had their dynastic capital at Cashel in County Tipperary. Toward the end of this period the Corcu Mo-Druad were defeated by the Desi, a tribe located to their east and located in east Clare and parts of present day Limerick. The Deis, in the fifth century had a center in what is now Waterford. Between the fifth and eighth centuries part of the clan moved northwest into eastern Clare and Limerick. By the tenth century, the Deis were a tribe on the rise and soon became known as the Deis Tuaiscirt or the Dal Cais. (O Croinin, pp. 224-225 and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dalcassians)

The map below describes Munster in about 750 CE. It can be found at http://sites.rootsweb.com/~irlkik/ihm/thomond.htm#dalcais

Political influence was accompanied by ecclesiastical influence. By the time of the synod of Raith Bressasil in 1111, when the Irish church was reformed in line with the Roman model, the Dal Cais had grown in influence and were able to have their tribal center at Killaloe made the center of the dioceses of Killaloe and Limerick, which mirrored the borders of the Dal Cais heartland. (O Croinin p. 915)

The Dal Cais was the tribe of the famous Brian Boru, who ultimately became High King of Ireland. Back in the diocese of Killaloe and Limerick the abbots of the monastery of Killaloe from the tenth to the thirteenth century were all members of the ruling Dal Cais dynasty or one of its collateral branches. (O’Corrain, p. 53) One of the losers at Raith Bressasil was the diocese of Kilfenora. Kilfenora had been a bishopric prior to the synod but did not retain that title in 1111. As will be noted later in the historical background on Kilfenora, the community, determined to again be a bishopric, began a program of renovation of the cathedral and the carving of High Crosse. The photo to the right is a view of Saint Flannan’s Cathedral from across the River Shannon.

Ecclesiastic History

There were numerous monasteries founded in the area of present day County Clare. Several were founded in the 6th century; including Bishop’s Island, Ceannindis, Drumcliff, Inchicronan, Inish-loinge, Inishmore, Inis-tuaischert, and Scattery Island. A list of early monasteries, found in a “List of monastic houses in County Clare” is below. It will be noted that there is little information about many of these foundations. This list does not include several sites that have High Crosses. These sites are Kills, Kilvoydan and Skeaghavannoe.

To visit the site go to: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_monastic_houses_in_County_Clare

Bishop’s Island Monastery,Gaelic monks, founded in 6th century by St. Senan

Canon Island MonasteryEarly site possibly founded by St. Senan

Ceannindis MonasteryEarly site founded in 6th century by St. Comgan of Killeshin

Drumcliff Monastery, Gaelic monks, founded in 6th century possibly by St. Colmcille

Dysert O Dea MonasteryGaelic monks, founded prior to 735 by St. Tola

Enniskerry MonasteryEarly site

Ennistimon MonasteryGaelic monks

Feenbish MonasteryGaelic nuns, founded by St. Brigid of Conchraid

Glencolumbkille AbbeyColumban monks, founded by St. Columcille

Illaunmore MonasteryGaelic monks, founded in 7/8th century

Illaunmore Lough DergPossible early site

Inchicronan PrioryEarly site, founded in 6th century by St. Cronan of Tuamgraney

Inishcealtra MonasteryEarly site, founded in 653 by St. Camin

Inishloe AbbeyGaelic monks, founded by Turlogh, King of Thomond

Inish-loingeEarly site, founded 6th century

Inishmore MonasteryEarly site, founded in 6th century by St. Senan

Inis-tuaischertEarly site, founded in 6th century by St. Senan

Kilballyowen MonasteryPossible early site

Kilfenora MonasteryCeltic monks, founded by St. Fachnan

Killadusert MonasteryGaelic monks

Killaloe MonasteryGaelic monks, founded in 10th century

Killinaboy MonasteryEarly site, founded by Ingrid Baoith

Kilnagallech MonasteryGaelic nuns

Mucinis MonasteryEarly site

Noughaval MonasteryGaelic monks, founded by St. Mogua

Oughtmama MonasteryEarly site, associated with three Sts. named Colman

Rath MonasteryGaelic monks, founded by St. Blathmac

Rossmanagher MonasteryGaelic nuns

Scattery Island MonasteryCeltic monks, founded in 6th century by St. Senan or St. Patrick

Tomfinlough MonasteryGaelic monks

Tomgraney AbbeyGaelic monks

Tulla AbbeyGaelic monks

Described below are High Crosses located at the ancient monastic sites of Dysert O’Dea Cross , Inis Cealtra, Kells, Kilfenora, Killaloe, Killnaboy, Kilvoydan, Noughaval, and Skeaghavannoe. These were not the only monasteries in present day County Clare during this time period. One example would be the monastery on Scattery Island in the Shannon estuary. The monastery continued after 1111. There are extensive ruins on the island, including a round tower, but no High Crosses.

In the entries below, where there is some knowledge of the history of the site, that is offered, along with background on the primary saint(s) as introduction to the description of the cross(es).

Dysert O’Dea

The Monastery: According to tradition, St. Tola founded the Dysert O’Dea monastery. The year of its establishment is not clear. However, the Annals of Ulster for 738 refer to the death of St. Tola, Bishop of Cluain. Other dates in the 730’s have also been offered for his death. It is likely, therefore, that the monastery was founded in the late 7th or early 8th century.

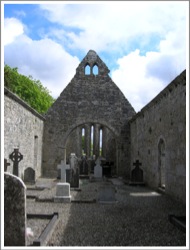

In addition to the High Crosses, which will be described in detail below, there are additional features of the monastery that are of note.

There is a roofless chapel on the site that dates to the 12th century, (see the photo to the right). It has been suggested that this church stands on the site of an earlier church. One highlight of the church is its Romanesque doorway as seen in the photo to the left. This doorway features 12 human heads carved on the arch. O’Farrell suggests each head was carved as an image of one of the monks who belonged to the community at the time. Some heads depict animals. Each head is certainly distinctive. (O’Farrell, p. 27)

Another feature of the site is the stump of a round tower, which can be seen the photo to the right.

The Saint: Little is known about Saint Tola. There are different views concerning where he lived as hermit and abbot. He was likely born in the second half of the seventh century. His tribe may have been the Galengi who lived in a district known as Galenga or Gallen in parts of Counties Carlow and Kildare. As a hermit, Tola lived in a place called Desert Tola, which seems to be present day Dysert O’Dea in County Clare. “The Irish Genealogist, Duald Mac Firbis, enters Tola, bishop, from Disart Tola — said now to be Dysart O’Dea, county Clare in Upper Dal-Cais.” (Saint Tola of Disert Tola)

Tola is associated with the monastery at Clonard in County Meath, where he was bishop. It was after 700 CE that he was supposed to have established the monastery in County Clare known as Disert Tola or Dysert O’Dea. He seems to have returned to Clonard as bishop or abbot prior to his death between 734 and 737. (Tola of Clonard) However, T.J. Westropp, in an article entitled “Churches with Round Towers in Northern Clare” states that he could find no information about Tola’s time in County Clare. (Westropp, Churches with Round Towers)

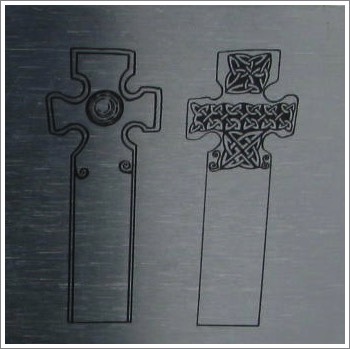

The Cross in the Field:

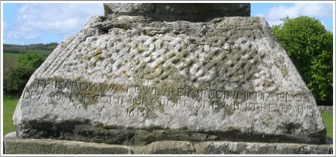

The cross and its base stand on a tall platform that is just larger than the base, as seen in the photo to the left. According to the inscription on the east face of the base the cross was repaired by Michael O’Dea in 1683 and re-erected by F.H. Synge in 1871. The Commissioners of Public Works later placed a much larger and lower platform around the whole. The roof of the cross is modern. (Harbison, 1992, p. 83) The cross stands 9 feet (2.77m) tall, is 3 ft. 4 in. (1.02m) across the arms and the base is 1 ft. 8 in. (50cm) tall.

East Face:

The base has a panel of interlace, part of which was cut away to create a surface for the inscription mentioned above. See the photo below.

The shaft of the cross contains an image identified as a bishop or abbot as seen in the photo below left. The figure wears a mitre what was originally pointed. In the left hand is a crozier. The right hand is missing and appears to have originally been an insert. (Harbison, 1992, p. 84) Writing in 1899, George MacNamara simply assumes that the figure represents Saint Tola. (MacNamara, 1899, p. 249) While this identification is appealing, it is by no means certain. What is certain is that more than 350 years after the death of St. Tola, no one knew what he looked like.

The head of the cross has a depiction of the crucifixion of Jesus. Harbison notes that Henry suggested that the figure appears to be more consistent with Christ triumphant than crucified. (Harbison, 1992, p. 84)

The head is seen in the photo to the right.

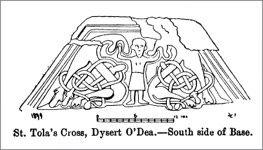

South Side:

The Base contains a very stylized image of Daniel in the Lion’s Den as seen in the illustration below left. (MacNamara, 1899, p. 248) Harbison notes that Porter suggests this image may represent Gunnar in the Serpent’s Den. This refers to a Norse legend that would have been known from the 10th century. Deciding between the two identifications of the image calls on the interpreter to read the mind of the artist as both stories have similar content. This image is very different than most of the High Cross images of Daniel in the Lion’s Den.

Below this carving is an inscription that was added in the 19th century. It reads: “Re-erected by Francis Hutchinson Synge of Dysart Fourth son of the late Sir Edward Synge Bar and Mary Helena his wife in the year 1871.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 84)

The photo below right shows both the North and South sides of the cross shaft.

The South Shaft. (MacNamara, 1899, p. 251) Harbison describes this side of the shaft as follows:

Harbison describes this side of the shaft as follows:

"S 1: Two animals back to back, their heads turned around to face one another. Each devours the end of an (animal?) interlace which coils around their respective bodies.

"S 2: Two interlaced animals with a human head between their snouts. A narrow band of interlace coils between them.

“S 3: A single animal, now headless because the top of the panel has been damaged. It coils to form a figure of eight, interspersed with a narrower band of interlace.

“S 4: Meander patterns interlinking horizontally and vertically.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 84)

West Face

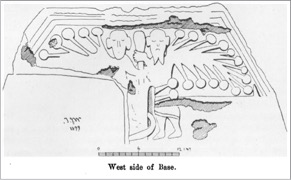

The base has an image that has been interpreted in a number of ways but likely it represents Adam and Eve in the garden. The illustration to the left below is from MacNamera. The image to the right shows the same scene as it appeared in 2008.

Writing in 1899, MacNamara suggested the two figures are angels whose wings are “a series of banjo-shaped members, intended, as I take it, to represent feathers.” The angels hold a staff between them. Near their legs is a “sickle-shaped object, to which two ‘feather(s)’ . . . appear to belong.” MacNamara offers two interpretations. It may refer to a legend connected to St. Tola that is now forgotten. Or, it may represent the killing of a badger-monster “securely chained for ever by St. Mac Creiche . . . to the bottom of Loch Broicsighe.” (MacNamara 1899, p. 248-249)

Harbison notes that Roe believed it might represent St. Paul and St. Anthony of the desert breaking bread. This was a familiar story of the Desert Fathers that would have been widely known in Ireland at the time. (Harbison, 1992, p. 84)

Harbison prefers to interpret the scene as Adam and Eve in the garden. Adam, with a forked beard, is on the right and Eve on the left. The “sickle-shaped object” near their legs is the serpent winding itself around the tree. The “banjo-shaped members” are the boughs of the tree laden with fruit. (Harbison, 1992, p. 84)

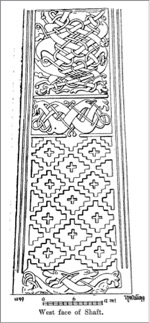

The shaft, like other aspects of the cross, is beautifully illustrated In MacNamara’s 1899 article as seen to the left below. (MacNamara, 1899, p. 252)

Harbison describes it as follows:

"W 1: A damaged horizontal panel of animal interlace.

“W 2: Sunken or relief crosses in panels with stepped edges.

“W 3: A horizontal panel of two crossing and interlaced animals.

“W 4: An upright panel of two interlaced animals intertwined with a narrower ribbon-serpent. The top of the panel has been removed.

“W 5: A panel divided into four quadrants with a circle at the centre, forming the motif of a cross, the expanded terminals of which break through the sides of a central square with bosses at each corner. There are sunken fields of L- and other shapes.” This panel is not illustrated to the left but can be seen in its current very worn condition on the photo below of the head and upper shaft of the west face, and in the illustration from MacNamara, also below.

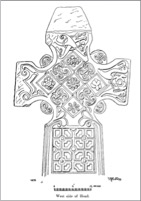

The Head of the cross is best described by MacNamara. “On the west face are five raised lozenges, 5 1/2 inches square, forming a cross, four of them ornamented with rosettes, and the remaining one with superimposed trefoils. Between the lozenges are scrolls of an earlier type, the whole producing a very pleasing effect. The arms are embellished with zoomorphs and the neck with a leaf pattern, but the former are much worn from exposure to the full brunt of the west wind.” (MacNamara, 1899, pp. 251-252)

North Side

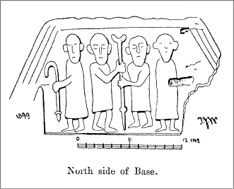

The Base contains a carving that has created considerable speculation. As seen below, it depicts four men, standing at various angles but all facing forward. The two in the center hold “a staff with a tau or crutch head, (MacNamara, 1899, p.249, also the source of the illustration to the left) or “a staff expanding or blossoming to left and right at the top.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 85) Buckley notes the “boss and sharp point at its lower end.” (Buckley, p. 248) There are two additional figures, flanking the men holding the staff on the left and right. The left hand figure holds what appears to be a short crozier. The right hand figure is missing the left arm. It may have held a staff. Buckley finds this scene to be consistent with two bishops, the outer figures, observing or blessing two monks as they take possession of a piece of land. While Harbison chooses not to speculate on exactly what this scene depicts. He finds some parallels in images of Joseph Interpreting the Dream of Pharaoh’s Butler or a story from the Paul and Anthony cycle of the Desert Father. As seen in the photo below, the scene is no longer clearly visible.

While it is speculative, Buckley offers support for his interpretation of the scene with a quote from the annals of the Abbey of Morimond in France. “The abbot, holding a wooden crutch or cross staff in his hand, went forward in front of the brothers . . . all reciting the Psalms. Having got to the place in the forest, or on the moorland, which had been given to them, the abbot planted a ‘cross’ staff thereon, sprinkling the spot with holy water all around and taking possession thereof, in the name of Christ.” He goes on to explain that the bishops of the adjoining area would be present as witnesses. (Buckley, pp. 248-249)

The Shaft, as seen in the illustration above to the right is described by Harbison as follows:

“N 1: Two animals with open mouths and raised paws facing one another, and having a narrow interlace coiling among them.

“N 2: Two interlacing animals with their heads facing upwards, and with a narrow ribbon of interlace coiling among them.

“N 3: A damaged panel with two animals with broad bodies being interlaced by a narrow ribbon.

“N 4: A fret pattern.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 86)

Cross in the Graveyard

In the graveyard there is a small cross that stands by an unmarked grave. The origins of the cross are unknown. The cross stands just over 2 feet (61cm) in height and is about one foot across at the arms. It has an imperforate ring. The arms extend just beyond the ring. There is no carving on either face of the cross.

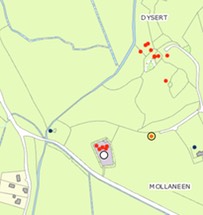

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 41, C 3. The site is named on the atlas as Dysert O Dea Church and Round Tower. Located west of the R476 between Ennis and Corroein. The field cross stands alone in a field, the church is down the hill with the graveyard cross located there.

Inis Cealtra

The Crosses

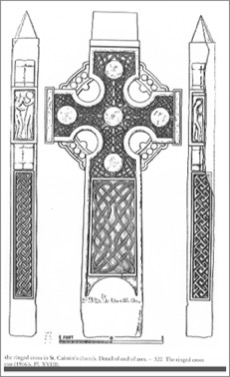

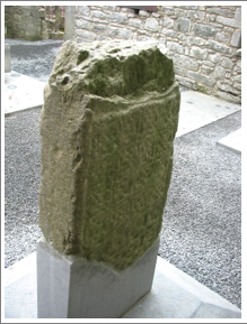

The Ringed Cross, Cross of Caimin

As illustrated in the two photos above, the ringed cross consists of fragments of the original cross: the head has been pieced together and is attached to an inner wall of St. Caimin’s church. The base and shaft are located outside near the round tower. The head is 37 inches (95cm) in height, 34 inches (86cm) across the arms and 6 inches (15cm thick). The base and shaft are 33 inches (85cm) tall, 16 inches (40cm) wide and 6 inches (15cm thick).

On the head, as pictured above, three characteristics are clear. There are four bosses, one in the center, one on the upper extension and one each on the arms. Rolled moulding is clearly visible on the cross and the ring. The cap is roof shaped and has no decoration.

What is not so clear in the photos above, but is clarified by the illustration below, is that the bosses are set in a pattern of interlace and the upper left segment of the ring has a meander decoration. Reporting on Inis Cealtra in 1916, Macalister offered illustrations of what the cross may have looked like. (Harbison, 1992, vol. 2, fig. 320)

The other face of the cross is against the wall. While parts of it are apparently broken away, Macalister suggests it may have been decorated.

The other face of the cross is against the wall. While parts of it are apparently broken away, Macalister suggests it may have been decorated.

The illustration reveals a figural carving on the end of each arm. On what is identified as the east arm Harbison identifies Samuel Anointing Saul or David. Macalister identifies Adam and Eve. Harbison has this to say about this panel: “Two figures stand opposite one another, clad to above the knees. The figure on the right holds up what seems to be a horn in the left hand, while that on the left extends the right fore-arm.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 99) In the illustration above the clothing described by Harbison is not apparent.

On the end of the west arm Harbison identifies Samuel Kissing Saul or David. The panel is damaged and only one figure is visible. Based on comparison with the East Cross at Galloon another figure is probably present. Any identification is hypothetical. (Harbison, 1992, p. 99)

On the west side of the shaft, facing St. Caimin’s, there is a rectangular panel that according to Macalister contains interlace. At the top is a boss that completes the lower section of the head. The sides of the shaft have interlace. The east face of the shaft is damaged. The lower half contains a square panel. (See photos below, west face left, east face right.)

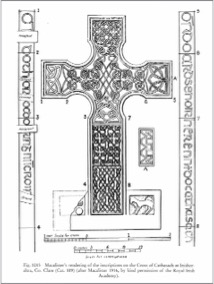

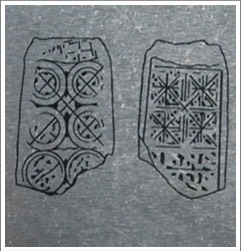

East Cross “Cross of Cathasach”

The East Cross, also attached to a wall in St. Caimin’s, is ringless and stands about 1.6m high. The edges have roll moulding. The surface of the cross is badly worn but Macalister produced a drawing illustrated below. (Harbison, 1992, vol. 3, fig. 1015) This drawing shows a very complex and lovely pattern, or more precisely, patterns of interlace covering the face of the cross. This cross is 5 feet 2 inches (1.6m) tall, 38 inches (97cm) across the arms and 4 inches (10cm) thick.

Like the West Cross, there is a rectangular panel on each side of the foot of the cross. The left side is broken off. On the right side there is a panel that shows a quadruped with a human leg hanging from its mouth.

There is an inscription on the east side of the cross that was interpreted by Macalister. It reads “Prayer for Tornoc who made the cross.” This may be a reference to the artist who carved the stone. On the west side is an inscription that reads “Prayer for the Chief Elder of Ireland, i.e. for Cathasach.” This Cathasach is mentioned below. He died in 1087. (Harbison, 1992, p. 98)

West Cross

The west cross is ringless and is attached to an inner wall of St. Caimin’s church. It is 6 feet 3 inches (1.9m) high, 38 inches (96cm) across the arms and 3 inches (7cm) thick. The right arm is broken. The edges of the cross have roll mouldings. No decoration is visible on the cross.

At the bottom of the cross, on each side of the foot is a square panel. Each bears a St. Andrew’s Cross. The terminals of each cross are squared. Harbison suggests this may imitate a bronze model. (Harbison, 1992, p. 98)

While the sides and back are not visible, Macalister reported that the back was plain.

Head Fragment

Liam de Paor (historian, archaeologist and political thinker) discovered a “finely-carved Romanesque head” during an excavation on Inis Cealtra. He identified it as a head of Christ related to a 12th century High Cross. It is in the possession of the National Museum in Dublin. The fragment is 13 inches (32cm) tall, 7 inches (19cm) wide and 7 inches (18cm) thick.

The head stands out in relief. Christ’s eyes appear to be closed. He has a flowing mustache and a beard. The head is tilted to one side, suggesting that Christ is represented as dead on the cross. (Harbison, 1992, p. 99, Vol. 2 Figure 322) This would make the head, and the cross it was part of, unusual in that on most of the High Crosses, where there is a crucifixion scene, Jesus is depicted with head erect and eyes open, more triumphant than defeated.

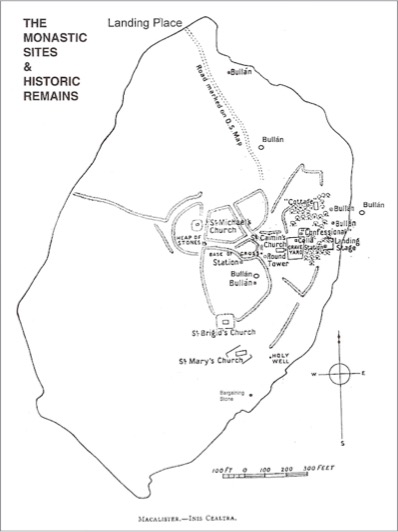

The Monastery and Saints

Inis Cealtra is a lovely island located in Loch Derg, just southwest of the Mountshannon harbor and not far from the shore. It is only accessible by boat. In the old Irish the name can be translated literally as Island Church, hence Church Island. . It is also referred to as “Holy Island” (Madden, p. 5) The ruins of numerous buildings are located on the island.

[The photo above looks to the mainland from the island.]

MacCreiche the Anchorite

"The first Christian association with the island came in the late fifth or early sixth century when a hermit named MacCreiche moved there and dedicated himself to a life of prayer. (Review, Macalister p. 130) The Confessional or Anchorite’s Cell on the island is said to be the site of his abode. According to tradition it contained four flag-stones “a stone at his back, a stone to each side, and a stone in front of him”. These prevented him from reclining or being comfortable even while he slept. He considered this discomfort part of his penance. (Review, Macalister, p. 132)

[The Confessional is pictured left.]

MacCreiche had a sacred tree. It was a Tilia, a lime or linden tree. Meehan quotes the Acta Sancti Columbae De Tyre Da Glas, a hagiography of Saint Colum mac Crimthan (see below), as reporting in part “a tree by the name of Tilia, whose juice distilling filled a vessel and that liquor had the flavor of honey and the headiness of wine.” (Meehan, pp. 469-70)

Saint Colum mac Crimthan

A monastery was first founded on Inis Cealtra around 520 by St. Colum mac Crimthan, a Leinster saint and one of the Twelve Apostles of Ireland. (Macalister p. 130). The Twelve Apostles were twelve 6th century Irish saints who all studied under St Finian at Clonard Abbey in County Meath. His name is also recorded as Columba or Mac Hy-Crimthainn. This same Colum was associated with the monastery at Terryglass (Tir Dha Ghlas or land of the two streams) in County Tipperary. According to this tradition Inis Cealtra was founded as one of a group of communities St. Colum established in the area of Loch Derg. Hagiography tells us that he was guided there by an angel, and that the same angel guided MacCreiche the anchorite to depart from the island. Colum brought numerous monks with him, a ready made community. Macalister suggests that at some point Colum left the district because it was too heavily populated. (Macalister, p. 130) Madden, on the other hand, believes Colum remained. He bases this on an entry in the Annals of the Four Masters that refers to Marcan, Abbot of Inis (Cealtra d. 1009), as Coarb (successor) of Colum Mac Criomthuinn.

[The map above shows the location of the ruins on Inis Cealtra. http://www.visitclare.net/holyisland.php]

The Annals of the Four Masters reports that “St. Colam, of Inis Cealtra, died of the mortality which was called the Cron Chonaill or Yellow Plague.” (Annals of the Four Masters, M548.9) Peter Berresford Ellis, historian and novelist, notes that “Medical historians agree that the descriptions of The Yellow Plague, referred to in the Irish records as Buidhe Connaill, point to it being a virulent type of jaundice in which the yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes are a result of excess bilirubin in the blood. Its devastation of Europe, including Ireland, in the 7th Century points to warm climatic conditions at the time as it is usually transmitted by the bite of the female mosquito. (sisterfidelma.com/interview.html)

[The photo to the left is the Church of the Wounded Men. It was probably a mortuary chapel for the O’Grady clan. The name may derive from the clan motto: “wounded but not defeated.”] (Madden, p. 27)

Successors to Colum

Several successors to Abbot Colum can be identified. The first was Nadcaoimh, a protege of Colum, who like Colum was also associated with the monastery at Terryglass. Fintan, who had been a student of Colum, followed next. He was succeeded by Colman Stellan. This Colman was one of the clergy of Ireland who received a letter from Pope elect John IV in 640. The letter concerned the Easter controversy. Colman Stellan died in 651. (Madden, p. 7)

Saint Caimin

St Caimin (Caminus, Cammine) is often credited with founding a monastery on Inis Cealtra. Madden believes, based on the work of Liam De Paor, that Caimin either founded a separate foundation or refounded/reformed the existing community. (Madden p. 8)

He is listed as Bishop-Abbot of Inis Cealtra and Terryglass. He was a scholar who wrote a commentary on the Psalms. A fragment of a later copy of his work still exists. Caimin was known for his sanctity and it was under his leadership the monastery developed as a center for learning. (Meehan, p. 470) He died in 654. “Repose of Camíne of Inis Celtra, and of Mael Aithgein, abbot of Tír dá Glas.” (Annals of Innisfallen, AI654.1)

The School at Inis Cealtra

[The photo right is the Church of Saint Bridget at Inis Cealtra.]

The school at Inis Cealtra was of some repute in Ireland and on the continent. Healy described it as “another celebrated nursery of ancient sanctity and learning.” (Healy, 512) It flourished during the seventh and eighth centuries but continued long after. This was a place “where the saints of old sought communion with God, and spent their lives in prayer, and fasting, and sacred study.” (Healy 513) As an example of the emphasis on learning in the monastery it is noted that in addition to Caimin’s commentary on the Psalms, St Coelan (Kalian), a monk of Inis Cealtra who lived in the eighth century, wrote a life of St. Bridget. It is also reported that students came not only from Ireland but from the continent as well.

The Eighth Century

Two additional leaders of the monastery, with 8th century dates, are mentioned in the Annals. They are Diarmait and Kellach. The death of Diarmait, an Abbot, is recorded in 749 by the Annals of Innisfallen. For the year 780, the Annals of the Four Masters records the death of Mochtighern, a wise man who was the son of Kellach, Abbot of Inis Cealtra.

[The photo right shows the ruins of St. Bridget’s in the foreground and St. Mary’s church in the background.]

Ninth and Tenth Century

Like so many other monasteries Inis Cealtra was plundered by Vikings. The first time was in 836. The Annals of the Four Masters reports that in that year the Danes burned the churches of Laichtreine, Inis Cealtra and Kill-Finche.

Nearly a century later, in 922, the Annals of Innisfallen record that Tomrar, son of Elgi, a Norseman plundered Inis Cealtra and “drowned (cast into the lough) its shrines and its relics and its books.” In this attack many monks were killed.

We also have information about leaders of the monastery during this period. For the year 898 the Annals of the Four Masters records the death of St. Cosgrath (Coscrach). He was another anchorite who lived and died at Inis Cealtra. He was known as Truaghan (the meagre). Tradition says he used the Anchorite’s Cell of MacCreiche mentioned above. (Review, Macalister, p. 132)

The Annals of the Four Masters mention two tenth century Abbots. They are Diarmaid and Maol-Keallaigh. One citation reads “M.951.4 Diarmaid, son of Caicher, Bishop of Inis-Cealtra died.” The other, a citation for 967, records the death of Maolgorm, the son of Maol-Keallaigh, Abbot of Inis Cealtra.

The Eleventh Century

[The photo below left shows the round tower and St. Caimin’s Church.]

Three inhabitants of the monastery in the eleventh century are noted: Corcran, Marcan and Cathasach.

Corcran was a celebrated scholar and served as Abbot. This suggests that the school at Inis Cealtra and its reputation for learning continued at least into the eleventh century. Marcan, brother of Brian Boraime, King of Munster and High King of Ireland, was abbot there up to his death in 1009. (MacAlister, p. 131) An inscription in stone, on one of the high crosses on the island, identifies Cathasach as “chief of the devout of Ireland”. It records his death in 1087. (MacAlister, p. 130)

An interesting historical side note suggests a close relationship between the monastery and Brian Boraime, king of Munster and High King of Ireland. As noted above, his brother was one of the abbots there. Healy goes on to tell us:

“Brian Boru repaired the great church about that very time, A.D. 1005-1010, and no doubt also restored the efficiency of the schools, for his biographer tells that ‘he sent professors and masters to teach wisdom and knowledge, and to buy books beyond the sea and the great ocean, because their own writings and books, in every church and in every sanctuary where they were, were burned and thrown into the water by the plunderers from first to last, and Brian himself gave the price of learning and the price of books to every one separately who went on this service.’” (Healy, pp. 521-522)

Twelfth Century

When the diocesan system was formalized in Ireland at the Synod of Rathbreasail in 1111, Inis Cealtra was assigned to the diocese of Killaloe. It is not clear when the monastery ceased to function but in 1210 St. Caimin’s church gave way to St. Mary’s as the parish church. After 1615, largely as a result of the Reformation, the buildings on Inis Cealtra were finally all left derelict.

Getting There, a personal journey.

In May of 2008 I was visiting Ireland. The goal of my two week trip was to locate and visit a group of Irish High Crosses. I wanted to see the cross or crosses and to spend some time at each site. I was hoping to experience the spirituality of each place. The afternoon of my first day in Ireland I found myself in Killaloe, a community in County Clare, along the beautiful Shannon River at the south end of Lough Derg. The Information Center there had just opened for the year that very day. The attendants there helped me make contact with a man named Ger Madden. Ger is a local historian who has a special interest in Inis Cealtra. In fact he has written a booklet on the subject “Inis Cealtra: Jewel of the Lough”. He and I made arrangements to meet the next day in the late morning.

[The photo left shows the round tower.]

I found Ger at the Mountshannon marina where he takes folk to the island on a regular basis. I was his only customer for the day, so we took a small motor boat out to the island. He dropped me off at a dock on the north side of the island. He returned to the harbor and left me alone for a couple of hours so I could explore the island in peace.

There's a caretaker on the island who provides some security, maintains the grounds and cares for some cattle. Otherwise the island was deserted. I met the caretaker while he was weed eating in the cemetery. We visited for a few minutes, but mostly I had the island to myself. There are numerous ruins and sacred sites on the island. I was particularly interested in the three crosses described above.

I had purchased a copy of Ger’s book at the harbor so I had a map of the island with the locations and information about the various sites. With or without the booklet the sites are well signposted as the collage below illustrates.

As I moved around the island, from one ancient site to the next I felt the thinness of the place, the presence of the Holy, or, as J. Phillip Newell might say, I found myself “Listening for the The Heartbeat of God.” I thought about the countless souls who had journey here across the centuries in search of God, of holiness, of renewal, of a strong education steeped in scripture, of a community where life was prayer. I thought of those who had and, like me, continue to make pilgrimage to this Holy Island.

A couple of hours later I met Ger at the dock and he took me back to Mountshannon harbor. Dark clouds were rolling in from the southwest and I sat in my car and ate my lunch while it poured rain for a few minutes. By the time I drove away I was refreshed and renewed in body and spirit. I left Inis Cealtra in my wake, looking for more of the sacred places of the Emerald Isle. But it is always in my heart as one of the very special holy places I have visited in Ireland.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 42, G 3. Located on an island in Loch Derg, the site is accessible only by boat from Mountshannon.

The map is from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Kilfenora Crosses

The Monastery and the Saint:

Little is known of the first four hundred years of the history of the monastery and church at Kilfenora (see photo right). A voluntary community project, the “Kilfenora Timeline” exhibition opened in the spring of 2013. It is housed in the 12th century St. Fachtnan's Cathedral at Kilfenora. There are only two entries before 1000 CE They are both from the sixth century and read as follows:

“560 A.D. St. Fachtnan establishes a monastery in Kilfenora. Born in West Cork and a student of both St. Ita and St. Finbar, Irish Martyrology lists Fachtnan as Bishop of Ross and Kilfenora. A sixth century teacher who lost his sight and, unable to read or write, prayed to God for his sight to be restored. His prayers were answered and it is suggested that in thanksgiving for this favour, he founded a monastery in Kilfenora. Following the establishment of the monastery, tradition says that St. Fachtnan lived the remainder of his life in Kilfenora and died there circa 590 A.D. His feast day is remembered on Dec. 20th.

“570 A.D. A raid by the King of Connaught on the people of Corcomroe taking all their cattle. This represented all their wealth at that time.” (Kilfenora Timeline)

Corcomroe is the name given to a pre-twelfth century tuath or territory that coincided with the boundaries of the diocese of Kilfenora

Any information we have about St. Fachtnan is hagiographic. As early as the nineteenth century there was a question about whether a Fachtnan established the monastery or whether the church was simply later dedicated to him. The writer suggests that the founder was not Fachtnan of Ross but another of the same or similar name. (An Ecclesiastical History of Ireland: From the Introduction of Christianity: by Patrick Joseph Carew, 1838, pp. 432-433)

Just inside the doors to the present Cathedral there is an effigy of a bishop (image left). As we will learn below, Kilfenora was an episcopal see.

Kilfenora, or Cill Fhionnurach in Irish, means “Church of the fair white brow.” (http://www.catholicireland.net/saintoftheday/st-fachanan/)

While the Irish Martyrology mentioned above in the Kilfenora Timeline lists Fachtnan as Bishop, it is unclear when Kilfenora became an episcopal see. The Timeline picks up again at 1002 CE with the following entries:

“1002 A.D. Newly crowned High King of Ireland Brian Boru places enormous levies on the people of the Kilfenora area to maintain his army. During his reign the people of Corcomroe paid annual levies of 1,000 cows, 1,000 oxen, 1,000 rams and 1,000 cloaks.

“1055 A.D. In a raid into Corcomroe, Murough, grandson of Brian Boru, burned the Abbey of Kilfenora, plundering houses, and killing 100 inhabitants.

“1056 A.D. Renovation of the church is commenced.

“1058 A.D. Renovation of the church is completed and is considered one of the finest churches in Ireland.

“1088 A.D. According to the Annals, Kilfenora is plundered three times this year by troops from Connaught led by Roderic O’Connor, who left scarcely any cattle or people he did not kill or carry off.”

The next entries in the Timeline take us into the twelfth century, the time period when the High Crosses of Kilfenora were carved and erected as indicated by the text for 1152 CE

“1111 A.D. The Synod of Rathbreasail; the European Diocesan system was introduced. Kilfenora at this time did not retain its Bishopric.

“1128 A.D. Finguirt, Confessor of Corcomroe, died in the Cathedral of Kilfenora. Confessor in Irish was ‘Anamchara’ meaning soul friend and was considered so important to novice monks that to be without one was like a body without a head.

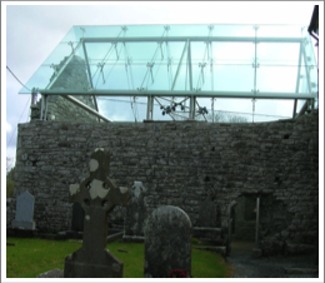

“1152 A.D. At the Synod of Kells, under Cardinal John Papro, tribal chiefs of Corcomroe renewed their efforts to have the Bishopric retained. In a show of unity, renovation of the cathedral and the carving of high crosses began. (The image to the right shows part of the transept of the 12th century cathedral. It is covered to protect the High Crosses that are displayed inside.) Such was their determination that Kilfenora succeeded in retaining its standing and was listed as one of the thirteen Diocese in the province of Cashel. One of the smallest Diocese in the country, it also included the Aran Islands. Renovation on the cathedral at this point can still be viewed in the east window of the Chancel. The carvings at the top of the two pillars which divide the three lights date from this time.

“1152 A.D. At the Synod of Kells, under Cardinal John Papro, tribal chiefs of Corcomroe renewed their efforts to have the Bishopric retained. In a show of unity, renovation of the cathedral and the carving of high crosses began. (The image to the right shows part of the transept of the 12th century cathedral. It is covered to protect the High Crosses that are displayed inside.) Such was their determination that Kilfenora succeeded in retaining its standing and was listed as one of the thirteen Diocese in the province of Cashel. One of the smallest Diocese in the country, it also included the Aran Islands. Renovation on the cathedral at this point can still be viewed in the east window of the Chancel. The carvings at the top of the two pillars which divide the three lights date from this time.

“ Seven stone crosses are associated with Kilfenora. Six crosses survive. The positioning of these would appear to outline the boundary of the original monastic enclosure which indicated a diameter of not less than 300 m. The remains of these crosses can be seen in the transept of the cathedral which is in state protection under the authority of The Office of Public Works. The seventh cross was removed by Dr. Richard Mant, Bishop of Killaloe, in 1821 and now stands in the cathedral at Killaloe.” (Kilfenora Timetable)

The Crosses

Below are photographs and descriptions of six of the seven Kilfenora crosses. Two complete crosses and shaft fragments of two others are on display in the re-roofed transept of the cathedral. An additional cross is in a field to the west of the cathedral. A sixth cross, the one moved to Killaloe in 1821, is also considered below.

The Doorty Cross

This cross takes its name from a family who used the lower portion of the shaft upside down as a tombstone until it was discovered it was part of a cross and was reassembled. Below, to the left, is the east face of the cross with the south face also visible.

The East Face

The lower portion of the east face, seen to the right, appears to be one image. At the top are two clerics. The one on the left holds a "drop-head" crozier while the one on the right holds a "tau-shaped" crozier. The "tau" crozier suggests an identification for the right figure as that of St. Anthony of the Desert. This in turn suggests that his companion is St. Paul, a fellow-hermit. Both are late 3rd or early 4th century figures. They stand with their arms entwined.

The base of St. Anthony's crozier is thrust into the neck of a strange winged beast below the feet of the saints. This suggests an image of St. Anthony overcoming evil.

The beast in turn is atop two human heads. It appears that one of the beast's legs is on the head of the human figure to the right. "This figure may hold the bottom of one of the beast's legs in its left hand, while beside it -- to the left -- a similar figure raises its left hand to catch the beast's other leg, and its right hand is raised to ward off the claw-like tail of the beast above it." (Harbison, 1992, p. 114) It is possible there was originally more of these figures below the present bottom of the shaft.

The image may lift up St. Anthony's struggle against the forces of evil on behalf of humanity. The human family constantly struggling with the forces of evil.

The upper part of the shaft and the head of the cross, seen to the left, have an image of a bishop or an abbot. Given the fact that the Synod of Rathbreasail in 1111 CE established the episcopal system for all of Ireland, it is likely this is intended to be a bishop. The crozier he holds in his left hand has a volute head. He wears a pointed mitre. There is an angel on each of his shoulders. High right hand points downward as if to indicate the scene below.

Peter Harbison describes the North Side (left) and the South Side (right) of the Doorty Cross as follows:

"North Side: On the shaft an irregular interlace, possibly terminating in an animal head above left, is surmounted by a checker-board pattern.

"South Side: Above a single human head there is a figure with right hand down by the side and with the left hand placed across the chest, holding a book. Above is an interlace. The end of the arm is undecorated." (Harbison, 1992, pp. 114-115)

West Side:

The head of the cross (left) has an image of the crucified Christ. There is a bird above and below each arm. The figure must have originally extended into the top of the shaft but that area of the cross is extremely worn.

The lower part of the shaft (right) is described by Peter Harbison as follows: "On top of a shingled roof, resembling those found on top of other (earlier) High Crosses, a man stands beside -- though probably meant to be understood as being astride -- a horse, the reins of which he holds. (Harbison, 1992, p 114) Some have interpreted this as the Entry of Jesus into Jerusalem. Harbison suggests it may "represent an apocalyptic horseman." (Harbison, 1992, p. 115)

The upper part of the shaft (lower right), above the head of the horseman, is composed of "ornamental scrolls interlaced by what would seem to be a narrow-bodied animal, terminating in a figure of eight formation at the top. (Harbison, 1992, p. 115)

The North Cross

This is an unringed cross that is 6 feet 9 inches (2.06m) tall, 29 inches (73cm) across the arms and 6 inches (16cm) thick. Before being moved into the transept for protection, it was located near the north-west corner of the Cathedral churchyard. It is now, ironically, located in the southeast corner of the transept. What was the east face of the cross now faces the transept.

This east face (left) is decorated with a boss in the center and roll mouldings on the edges. These mouldings curl into spirals at the top of the shaft.

On the west face (right) there is decoration on the head of the cross. Peter Harbison describes it as follows: "Right across the arms there is a field of Stafford knots. Beneath it there is a square panel consisting of four interlinked knots of pointed triangular interlace, with a double spiral on each side of it at the top of the shaft. The top has a panel of pointed interlace, flanked beneath and on the right by a meander motif." (Harbison, 1992, p. 115) The images below from the display plaques illustrate the design on each face of the cross.

The South Cross (lower shaft)

This partial cross shaft was found in 1954 and was placed south of the door to the Cathedral before being moved into the transept for protection. It is about 6 feet 4 inches (1.95m) tall, 28 inches (72cm) wide and 7 inches (18cm) thick. There is roll moulding along the sides that curls into spirals at the bottom of the shaft. The only discernible carving is toward the top of the shaft on each face.

Ironically, the South cross is now located in the northwest corner of the transept. What Peter Harbison describes as the east face (right) now faces south. "The east face has a horizontal panel of Stafford knots, with a panel of closer-meshed interlace above it, at the present top of the shaft." (Harbison, 1992, p. 115)

The West face (not pictured) has a partial panel of interlace near the top.

Shaft-fragment

This shaft-fragment is identified by Harbison as #137, Shaft-fragment in the Cathedral chancel. (Harbison 1992, p. 116) It stands in the northeast corner of the transept and is mounted on a modern lower shaft segment. The side facing south is described by Harbison as the West Face.

"The west face (left) has interlacing forming circular devices, above which is a segment of a circle of interlace, suggesting that it may have formed part of the decoration of the ring of the head.

"The east face has square panels of interlace, each subdivided into four, and beneath them, a thick-banded interlace. There are roll mouldings at the corner" (Harbison, 1992, p. 116)

These designs can be seen more clearly in the image from the display plaque pictured below.

West Cross

The West Cross is located in a field west of the Cathedral. It has a perforated ringed cross with cylinders on the inside of the ring. This cross is 15 feet (4.60m) tall, 4 feet 4 inches (1.30m) across the arms and 12 inches (30cm) thick.

The East Face (left) is dominated by a figure of the crucified Christ. He wears a long robe that comes to below the knees. The scene emerges from the bottom of the shaft where "two rope-mouldings rise up along the centre of the shaft to open out near the top into a downward-pointing triangle containing a knot of interlace which supports Christ's foot-rest. On either side of the rope-moulding the shaft is decorated with false relief patterns of interlace, fretwork and 'angular' spirals." (Harbison, 1992, p. 115-116)

Two other features of note are not readily visible in the photos we have. Peter Harbison tells us that Christ has a square satchel or reliquary suspended around his neck that hangs on his abdomen. Harbison does not venture a guess as to the meaning of this. If it is a book satchel, it might represent Christ bringing the good news of the Gospel to the world.

The second feature of note is found on the top of the head of the cross. Harbison describes it as a lion-like animal "which manages to eat the end of its elongated tail." (Harbison 1992, p. 116)

The North and South sides of the cross are undecorated except for the end of the arm on the North side where there is a square of interlace.

The West face of the cross is filled with geometric design. Near the base there is a triangle of interlace pointing downward (see below left). "The upper half is filled with interlocking pelta-shapes, together with interlace forming four circular , and above it, four square devices (below right).

The Head "has a circular fretwork panel surrounded by a rope moulding. Two-strand interlace flanks it on the arms and on the shaft below, but the interlace at the top is single-strand." (Harbison, 1992, p. 116) This design could be interpreted as a sun symbol, perhaps representing the Risen Christ.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 41, B 2. Located in St. Fachtnan’s Church of Ireland in the town of Kilfenora. The church is located behind (north) of the Burren Centre.

The map is from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Cross at Killaloe

A cross was moved from Kilfenora to Killaloe in the nineteenth century. It is presently erected in the nave of the Killaloe Cathedral and will be described below related to Killaloe.

Killaloe Crosses

I. The Monastery and Diocese of Killaloe: from its origins to 1267

A monastery was founded at Killaloe in the late sixth century by St. Molua. Killaloe bears his name, the church of “Lua”. Molua, like many of the saints, abbots and bishops of early Christian Ireland was a member of a noble family, the Ui-Fidgente of the Limerick area. He was succeeded as abbot in 639 by St. Flannan who is remembered as the patron saint of the Killaloe diocese. Flannan was the son of Theodoric, King of Thomond, a ruler in the northern portions of Munster. Little else is known of the history of Killaloe before the tenth century. (Catholic Encyclopedia)

A monastery was founded at Killaloe in the late sixth century by St. Molua. Killaloe bears his name, the church of “Lua”. Molua, like many of the saints, abbots and bishops of early Christian Ireland was a member of a noble family, the Ui-Fidgente of the Limerick area. He was succeeded as abbot in 639 by St. Flannan who is remembered as the patron saint of the Killaloe diocese. Flannan was the son of Theodoric, King of Thomond, a ruler in the northern portions of Munster. Little else is known of the history of Killaloe before the tenth century. (Catholic Encyclopedia)

The photo to the right was taken in 2008 and shows St. Flannan’s Cathedral from the east.

The history of Killaloe becomes clearer in the early tenth century during the time of Viking incursions in Ireland. The Viking raids on this part of Ireland began in the ninth century. By 861, a Dane named Yorus had established a longphort or raiding fort in the general area of present day Limerick. In the tenth century a town was established on King’s Island in present day Limerick. For more than 100 years, there was on-going conflict between the Vikings and the Irish. In 968 the Irish captured Limerick, only to lose it again the next year. In the early eleventh century, while Brian Boru was King of Munster, the Irish captured it again and the Viking population was gradually absorbed into Irish society. An excavation in Limerick reported on in 2003 showed that by the early eleventh century, thanks to the Vikings, Limerick was a major trading hub. (O’Donovan p. 40)

During the eleventh and twelfth centuries attacks on Killaloe came not from the Vikings but from Connacht. There are attacks on record for the years 1062, 1081 and 1084. In 1088, Domnhnail MacLochlainn, King of Aileach, in Ulster, destroyed Kincora. Kincora was the residence of the king. It was located just over 1000 feet to the west of the monastery, known as Killaloe. (Westropp p. 407, 410) In 1116 Turlogh O’Connor burned Kincora, and he did it again in 1119. In 1185 the first cathedral church was destroyed by Cathal Carrach of Connacht. It is unclear whether the monastery was attacked and/or destroyed each time Kincora was attacked, but it seems likely.

As noted above Killaloe gained prominence during the reign of Brian Boru who was born at Kincora. He became King of Munster in 978 and Kincora, was his capital. Like other Irish kings of the time, Brian sought to bring the most important of the monasteries in his kingdom under his control. In his early years as King of Munster he rebuilt the palace of Kincora and the churches of Killaloe, Inniscaltra and Tomgraney. He was also responsible for the construction of the Round Tower at Tomgraney. When he gained the High Kingship of Ireland in 1002, Kincora became the functional capital of Ireland. (Ferrar, p. 10)

The artists rendering, to the left, of what Brian may have looked like was found at aohflorida.org, Ancient Order of Hibernians: Florida State Board, 9/2015.

The abbots of the monastery from the tenth to the thirteenth century were all members of the ruling Dal Cais dynasty or one of its collateral branches. Eight abbots are mentioned in the annals and genealogies. Scandlan mac Taidc (ob. 991, AI), was probably a member of the Ui Ailgile. He was succeeded by Marcan mac Cennetig (ob. 1010), brother of Brian Boru. He was also abbot of Inniscaltra and Terryglass. Next came Cathal mac Maine (ob. 1013). His father was Brian’s first-cousin.

Echach of Ui Ailgile (ob. 1027, AI; 1028, AU), followed Cathal as abbot. He was succeeded by Macc Endai (ob. 1030) of the Cland Echach Macc Endai founded a significant hereditary ecclesiastical family. He was followed by Coscrach mac Aingeda (ob. 1040), second cousin of the king, Donnchad mac Briain. The eighth abbot of Killaloe for whom there is an obit was Tadc ua Taidc (ob. 1083, AI, ATig). The date of his death indicates that one or more abbots ruled the monastery between Coscrach mac Aingeda and his time as abbot. We do not know the identity or number of these abbots. (O’Corrain, pp. 52-53)

The Dal Cais dynasty, of which Brian Boru was a member, was involved early in the church reform movement that culminated at the Synod of Raith Bresail in 1111. One of the leaders of the reform movement, Domnall Ua hEnna (1023-98) was a member of the hereditary clerical family and bishop of Killaloe. He was the leader of the reform movement up to his death.

Dal Cais dominance of church leadership in what became the diocese of Killaloe continued after the establishment of the diocesan system in Ireland in 1111. For about 150 years, every canonical bishop of the Killaloe diocese, except one, was a member of the Dal Cais. (O’Corrain, pp. 57-58)

These bishops were:

Gilla Patrick Ua hEnna, dates unknown

Domnall Ua Lonngargain, bishop 1131-1137

Tadg Ua Lonngargain, bishop 1138-1161

Donnchad Mac Diarmata Ua Brian, bishop 1161-1164

Constantin Mac Toirrdelbaig Ua Brian, bishop 1179?-1194

Dairmait Ua Conaing, bishop 1194-1195

Conchobhar Ua hEnna, bishop 1201?-1216)

Domnall Ua hEnna, bishop 1216-?

Robert Travers, bishop 1217-1226

Domnall O’Cenneitig, bishop 1231-1252

Isoc O’Cormacain, bishop 1253-1267 (GCatholic.org, Diocese of Killaloe, Ireland)

As his name suggests, Robert Travers was the exception to the rule. Following the death of Conchobar in 1216 there were rivals for the episcopal succession at Killaloe. Donal Ua hEnna was elected in 1216 but Geoffrey de Marisco, the justiciar of Ireland for the English throne, sought the position for his nephew Robert Travers without canonical election. Exactly who exercised episcopal authority during that time is not clear. In 1221 Domnall was elected once more but Robert continued to claim the title.

II. The Crosses at Killaloe

The Limestone Cross from Kilfenora

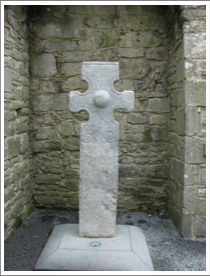

The limestone cross described below was carved and originally located at Kilfenora. This cross was moved from Kilfenora to Killaloe in 1821 by Dr. Richard Mant, Bishop of Killaloe and Kilfenora (Church of Ireland). When Harbison described it in his 1992 The High Crosses of Ireland, it was built into a wall on the interior of the cathedral. It now stands in the nave of the cathedral, with some modern parts added to make it whole .

The cross stands 13 feet 9 inches (4.20m) in height, 39 inches (1m) across the arms and 5+inches thick..

The West Face (left) has interlace beginning near the top of the shaft and covering the arms. This decoration is not visible in the photo to the left taken in 2008 by the author, but can be seen in some detail in the photo to the right taken in 1930. (Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 400) It was this side of the cross that was attached to the wall of the cathedral.

The East Face (below right) has an inscription about the center of the shaft. It is in Latin and is dated 1821, acknowledging the moving of the cross from Kilfenora to Killaloe. The gist of it seems to be along these lines. “Here you see a cross from the fields of Kilfenora, not fully aware of the situation of decay it was in. This now has the favor of a home in Killaloe, erected with care in the old church by R.M.S.T.P. [Richard Mant] serving bishop of the diocese, A.D. 1821.”

The carving on the East Face is limited to the top of the shaft and the head of the cross. At the top of the shaft is a square panel that contains fretwork. In the center of the head is an image of the crucified Christ. His hands are outstretched and he is clad in a long robe down to his ankles. In the areas above and below the right arm of Christ and above his left arm are knots of interlace. That on the left is double strand. “Under his left arm, four animal-heads emerge from a whirl. Above Christ's head there is a simple, single-strand interlace." (Harbison, 1992, p. 120)

The photo on the left is from a plaque located in the church at Kilfenora describing the cross at Killaloe.. That on the right was taken in 2008 by the author.

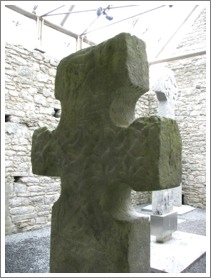

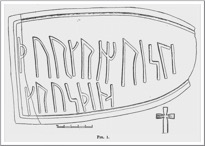

The Killaloe/Shantraud Fragment

Set on a pedestal in the nave of the Cathedral is a very unique stone whose provenance is not clear. Could it be a fragment of a High Cross that had its origins at the Killaloe monastery? The cross fragment is 27 inches (68cm) tall, 17 inches (44cm) across and 9 inches (22cm) thick.

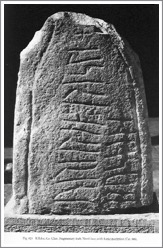

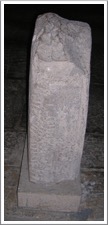

When Macalister took note of it in 1916, it was built into a wall of the Cathedral. Only one side was showing and Macalister was surprised to see that it contained Runic letters. This turned out to be an inscription that was clear to read: “Thorgrim raised this cross.” As shown in the illustration to the left above, Macalister took this to be the dexter arm of a cross. At that time only two other Runic inscriptions had been found in Ireland. This made the find extremely unique and interesting. The illustration above right is from Macalister, p. 493. The photo below left was taken by the author in 2008, that to the right is from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 401.

When Macalister took note of it in 1916, it was built into a wall of the Cathedral. Only one side was showing and Macalister was surprised to see that it contained Runic letters. This turned out to be an inscription that was clear to read: “Thorgrim raised this cross.” As shown in the illustration to the left above, Macalister took this to be the dexter arm of a cross. At that time only two other Runic inscriptions had been found in Ireland. This made the find extremely unique and interesting. The illustration above right is from Macalister, p. 493. The photo below left was taken by the author in 2008, that to the right is from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 401.

The name Thorgrim is clearly Scandinavian. Macalister concluded that “Thorgrim, in spite of his heathenish name, must have been at least Christian enough to erect a cross.” (Macalister, p. 497) As noted above, the Viking raids on this part of Ireland began in the ninth century. By the early eleventh century a process of assimilation of these Vikings into the Irish population had at least begun.

The name Thorgrim is clearly Scandinavian. Macalister concluded that “Thorgrim, in spite of his heathenish name, must have been at least Christian enough to erect a cross.” (Macalister, p. 497) As noted above, the Viking raids on this part of Ireland began in the ninth century. By the early eleventh century a process of assimilation of these Vikings into the Irish population had at least begun.

At some point in time, the stone was removed from the wall and the other three sides became visible. What was revealed brought additional surprises and a reconsideration of the part of a cross that it represented. The first surprise was found on the East Side of the stone. There is an Ogham inscription that reads: “Prayer for Thorgrim.” So the same name appears in both the language of Scandinavia and that of Ireland.

At some point in time, the stone was removed from the wall and the other three sides became visible. What was revealed brought additional surprises and a reconsideration of the part of a cross that it represented. The first surprise was found on the East Side of the stone. There is an Ogham inscription that reads: “Prayer for Thorgrim.” So the same name appears in both the language of Scandinavia and that of Ireland.

The identity of Thorgrim may never be known. The two inscriptions suggest that he bridged the gulf between two cultures. That he is mentioned at all suggests he was a person of some importance. His sponsorship of a cross suggests he was, at least nominally a Christian.

The photo left was taken in 2008 by the author, that to the right is from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 401.

The presence of both an Ogham inscription and a Runic inscription on the cross, referencing the same name adds some complexity to the process of dating the cross. Runes continued in use, in a Scandanavian context, throughout the period under consideration. The gradual disappearance of Ogham inscriptions after the ninth century argues for an earlier rather than a later date for the cross fragment, perhaps as early as the late tenth century. That a Viking, presumably associated with Limerick might have had a cross erected might argue for a later rather than an earlier date. So a range of possible dates from the late tenth to the mid eleventh century, seems reasonable. This fits well with Macalister’s suggestion of the first half of the eleventh century as a date for the cross.

The second surprise following the removal of the stone from the wall was the presence, on what is now the south face of the cross, of a carving that appears to be Christ crucified. The orientation of this carving caused a reappraisal of the part of a cross the fragment represents. Harbison suggests that the fragment was from the upper portion of the shaft of a cross, just below the head. This aligns the carving on the south face properly and means the Runic inscription was carved sideways from bottom to top.

The carving identified as Christ crucified is primitive in style. The figure is off center to the right. Above Christ’s arms may be carvings of angels.

The photo to the left above was taken in 2008, that to the right is from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 402.

The primitive nature of the carving seems at odds with the power and prestige of the monastery in the early eleventh century. The monastery at Killaloe was experiencing the heights of power and prestige in the early eleventh century. Brian Boru was High King of Ireland and his capital of Kincora overlooked the monastery. He was a patron of the churches and monasteries in the area. Family members were in positions of leadership in the monastic communities of the area. The Viking community at Limerick was prospering in spite of conflict with the Irish under the leadership of Brian Boru. We might expect carving of a higher quality than we have on this cross fragment.

Where did this the cross, of which this fragment was a part, originate? Based on the importance of Killaloe as an ecclesiastic and political center in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, it is reasonable to think that there were crosses at the monastery. We know, from fragments such as this, that many crosses were damaged or destroyed over the course of time. The most that can be said is that it is possible that the cross from which this fragment comes may have had its origins at Killaloe.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 42, G/H 4. Located in Saint Flannan’s Cathedral in Killaloe, along the R463. The crosses are inside the nave of the church.

The map is from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Killinaboy Cross

This fragment is the head of a Tau Cross, one of only two in Ireland. It was originally near the road north of Killinaboy. It is on display in the Clare Heritage Centre in Corofin. The photos here are of the replica that is in the site of the original cross. The cross-head is 34 inches (87cm) tall, 27 inches (68cm) across the arms and 5.5 inches (14cm) thick.

The sides of the cross are flat, with no carving. The top of the cross has a face carved on each arm with three ribs running across between them. There is nothing to indicate the identity of the faces. However, the tau cross form is associated with St. Anthony the Hermit, who is identified by a tau shaped crozier. This led Harbison to speculate that the faces might belong to St. Anthony and St. Paul of the Desert.This may have been a wayside cross, intended to direct pilgrims to the church at Killinaboy. This church may have once housed a relic purporting to be a fragment of the “True Cross”. This is indicated by a double-armed cross in the west gable of the church.

To the left and right are the two faces on the top of the tau cross.

What may have been part of the shaft was discovered nearby. It does not, however fit with the head. (Harbison, 1992, pp. 128-129)

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 40, H 3. The Clare Heritage Centre Museum is located on Church Street in Corofin, the R460. It is open only on weekdays. There is a replica located at the original site for the cross. It is on the R476 8km from Kilfenora and 5km from Corofin. Park at the intersection with the L5260 and walk about 100m back toward Corofin. The replica will be on your right.

The maps are cropped from Google Maps.

Kilvoydan Cross

The Site

A Church and graveyard are located half a mile east of Corofin, on a hill overlooking the lake of Teadaun (Atedane on OS map) The patron of the church is unknown.

The Cross

22 yards south of the churchyard wall in the center of a small field is the old Cross of Kilvoydan. It consists of a base and head.

Base: A square block 3.5 feet (107cm) high, 26 inches (66cm) east west by 18 inches (46cm) north and south at base. it tapers toward the top. The socket measures 7x4 inches (18.10cm).

Head: Lies loosely in the socket-hole and is crude with much damage.

Getting There:

See the Road Atlas page 41,C 3. One half mile east of Corofin, on a hill overlooking the lake of Teadaun, on the River Fergus. The site is marked by the blue star on the map.

Off the R460 east out of Corofin take the first minor road to the right. It is one lane. Follow this to the top of a crest where you can see lake Teadaun and you will see a graveyard to your left. The cross-base and cross are just beyond the graveyard to the east. They are not in the graveyard. Down the lane to the right of the graveyard there is a house at the bottom of the lane. Mr. O’Laughlin owns the land the cross-base and cross are on. Ask permission as there are often cows in the pasture.

The map is cropped from Google Maps.

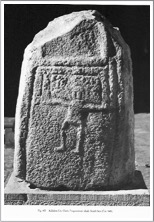

Noughaval Cross

In the Noughaval civil parish there is a ruined 13th century church. South of that there is a limestone cross that may be 12th or early 13th century. The cross is ringed and perforate. It stands 3 feet 10 inches (1.18m) in height, 26 inches (67cm) across the arms and it is 4 inches (10cm) thick.

The shape of the ring is not circular but resembles some other 12th century cross in this regard. The armpits are small and round.

There is circular decoration in the center of the head and the top of the shaft on the west face. These may have contained interlace. The east face is not apparently decorated. (Harbison, 1992, p. 158)

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 40, H 2. Noughaval is noted on the Road Atlas northeast of Kilfenora.

From the R476 between Kilfenora and Corofin just east of a place known by locals as the Milk Mart, turn north on a minor road. Follow this to the first road to the right. Just up this road you will see the modern church. Behind that are the ruins of an older church and the cross is in the graveyard. The location is noted on the map with a blue star. All the roads on this map appear on the Road Atlas.

The map is from Google Maps.

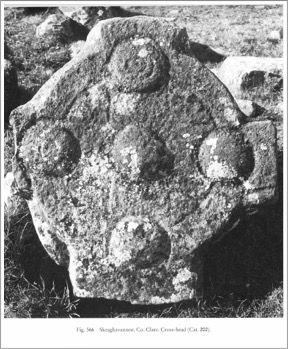

Skeaghavannoe or Kells Cross-head

The Site:

Nothing is known of the history of this site. It is located near a hill fort and may have been related to the fort as a church site.

The Cross-head:

The cross-head measures 28 inches (71cm) high, 27 inches (68.6cm) wide and 4 inches (10cm) thick. “The back is uncut, but the front is ornamented with five circular bosses marked with concentric circles, and formed into a Celtic cross by means of incised lines of no great depth.” (Macnamara p. 32)

(photo from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 566)

Getting There:

See the Road Atlas page 41 D 2/3. The Cross is located on a ridge a half mile from the Kells Bridge It is loose of the foundation of a small house or church located 67 yards north from a hill-fort.

Unfortunately the cross-head is completely overgrown with brambles and is not visible. It is off the road on farmland.

The map is cropped from the Historic

Resources Consulted

Catholic Encyclopedia (1913), Volume 8, Diocese of Killaloe, Michael Joseph Breen (9-2015)

Celt: Corpus of Electronic Texts, Annals of Ulster AD 431-1201 and Annals of the Four Masters 1 and 2. http://www.ucc.ie/celt/publishd.html

Clare County Library, clarelibrary.ie, Killaloe: Places of Interest (9-2015)

Clare Library, http://www.clarelibrary.ie/eolas/coclare/places/holy_island1.htm, Citing Journal of Thomas Dineley, 1681; A Description in 1845 in County Clare A History and Topography by Samuel Lewis, and records of the Iniscealtra Parish.

Dalcassians: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dalcassians

Ellis, Peter Berresford, Interview, http://www.sisterfidelma.com/interview.html

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Healy, John, Insula sanctorum et doctorum, Sealy, Bryers and Walker, 1890. http://www.clarelibrary.ie/eolas/coclare/places/holy_island1.htm II.

Ferrar, John, The History of Limerick, Ecclesiastical, Civil and Military, From the Earliest Records, to the Year 1787, A Watson, & Co., Limerick, 1788.

L.G. reveiw of, R.A.S. Macalister, The History and Antiquities of Inis Cealtra, Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 6, No. 21, March 1917, Irish Province of the Society of Jesus,

Macalister, R. A. S., On a Runic Inscription at Killaloe Cathedral, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Section C: Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature, Vol. 33 (1916/1917), pp. 493-498.

Macnamara, George U., “The Ancient Stone Crosses of Ui-Fearmaic, County Clare,” The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Mar. 31, 1900), pp. 22-33.

Madden, Gerard, Holy Island: Jewel of the Lough, A History, East Clare Heritage, 1990. Ger continues to offer trips out to the island.

Meehan, Cary, Sacred Ireland, Gothic Image, 2004.

O’Corrain, Donncha, Dal Cais — Church and Dynasty, Eriu, Vol. 24 (1973), Royal Irish Academy, pp. 52-63.

O Croinin, Daibhi, ed.; "A New History of Ireland: Prehistoric and Early Ireland", “High-kings with opposition, 1072-1166, Marie Therese Flanagan, Oxford University Press, 2005.

O’Donovan, Edmond, Limerick: New Discoveries in an Old City, History Ireland, Vol. 11, No. 1 (Spring, 2003), pp. 39-43.

Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae: http://omniumsanctorumhiberniae.blogspot.com/2013/03/saint-tola-of-disert-tola-march-30.html

Thomond: http://sites.rootsweb.com/~irlkik/ihm/thomond.htm#dalcais

Tola of Clonard: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tola_of_Clonard

Westropp, Thomas Johnson, Killaloe: Its Ancient Palaces and Cathedral. (Part I), The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 2, No. 4 (Dec., 1892), pp. 398-410.

Westropp, Thomas Johnson, “Churches with Round Towers in Northern Clare”, Clare County Library, http://www.clarelibrary.ie/eolas/coclare/archaeology/churches/st_tolas_cross.htm

What-When-How: (http://what-when-how.com/medieval-ireland/dal-cais-medieval-ireland/)