There are 10 High Crosses in County Dublin. They include: Clondalkin 2 crosses, Finglas, Jamestown, Kilgobbin, Kill-of-the-Grange north cross, Kilmainham and Tully roadside cross and cross in the field. The location of County Dublin is identified by the star on the map to the right.

In addition there are several cross fragments located in the National Museum in Dublin. These include: a shaft from a base in the graveyard at Drumcliff in Co. Sligo; sandstone fragments from Clonmacnois in Co. Offaly that may be part of a pillar or cross; the head of a High Cross from Clonmacnois; a cross shaft from Banagher in Co. Offaly; the head of a cross from Ogulla in Co. Roscommon.

A Brief History of County Dublin

General and Political History

Human habitation of what is now County Dublin dates to the early bronze age. Stone circles in the area date to around 2500 BCE. (O’Croinin p. ???) (Bronze-age Ireland by M.J. O’Kelly)

In the first century, the Drumanagh promontory fort, that seems to date to the late 1st century CE may have served as a bridgehead for a Roman invasion, a Roman trading colony or a native Irish settlement that traded with Roman Britain. That trade was involved is indicated by archaeological finds at the site. The fort is about 20 miles north of Dublin city.

Ptolemy, writing in the second century CE identified a native people in the area of the present County Dublin as the Blanii or Eblani. It is possible that their capital was Eblana, on the site of present day Dublin. (Before there were Counties)

Prior to the 5th century the area of the present County Dublin was under the control of the Laigin and was part of the Kingdom of Leinster. The Laigin were the main tribal group and the primary sub-groups in the area of the present County Dublin were the Dal Messin Corb and the related Ui Garrchon. The Dal Messin Corb were the dominant dynasty in Leinster until the 5th and 6th centuries when the Ui Dunlainge and Ui Cheinnselaig became more dominant.

In the fifth century, the sons of Niall Noigiallach, Niall of the Nine Hostages, founded the midlands kingdoms of the southern Ui Neill, Mide and Brega. The four sons were Coirpre, Loeguire, Fiach, and Maine. The area of Brega included present day counties Meath, north Dublin and south Louth. They were the leading kin-group until the arrival of the Normans in the 12th century.

In the mid-9th century a permanent Viking camp was established in part of the area of the present city of Dublin. The date was 841 CE. The Viking presence continued into the 10th and 11th centuries. At the Battle of Clontarf on 23 April 1014, Brian Boru, High King of Ireland defeated a Norse-Irish alliance and reduced the power of the Vikings and the Kingdom of Dublin.

In 1166, following the death of Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn, High King of Ireland, Ruaidri Ua Conchobair, King of Connacht took Dublin without opposition and exiled Dairmait Mac Murchada, King of Leinster. Three years later the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland began with the arrival of Strongbow, the Earl of Pembroke, who took control of Dublin and reinstated Dairmait as King of Leinster. Following Dairmait’s death Strongbow became King of Leinster.

Ecclesiastical History

There was no lack of early monasteries in the area of present day County Dublin from as early as 450 CE. Listed below are the early foundations as listed in the Monastic Houses of County Dublin. The list is not exhaustive as two sites with High Crosses, Kilgobbin and Kill-of-the-Grange, are not among those listed. The Kilgobbin site is of uncertain date. It could have been as early as the 7th c. or as late as 800-900. Kill-of-the-Grange was founded in the 7th century and is dedicated to St. Fintan of Clonenagh; With these two sites added there are 31 early Christian sites. Only 6 of these have extant High Crosses. Some history of those that do will be discussed as part of the examination of High Crosses in County Dublin below.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_monastic_houses_in_County_Dublin

For a map of these sites see: https://tools.wmflabs.org/osm4wiki/cgi-bin/wiki/wiki-osm.pl?project=en&article=List_of_monastic_houses_in_County_Dublin

Balally MonasteryEarly site: Baile Amhlaoibh or “town of Olaf” a Viking saint?

Ballyboghill MonasteryEarly Gaelic monks, prior to Anglo-Normans

Clondalkin AbbeyEarly Gaelic monks, founded in 7th century by St. Cronan (Mo-Chua), plundered 833, burned 1071, granted to Culdees possibly existed after 1111

Clontarf MonasteryEarly Gaelic monks, founded 550 by St. Comgall of Bangor

Crush MonasteryEarly Gaelic monks, 5th century by D. Daluan of Croibige

Dublin: Holy TrinityEarly monastery, 7th century, later Benedictine

Finglas MonasteryEarly Gaelic monks, 560 by St. Canice, probably destroyed by the Vikings ?

Glasmore MonasteryEarly Gaelic monks founded by St. Cronan (Mochua)

Glasnevin MonasteryEarly Gaelic monks founded before 545 by St. Mobi, ended after 10th c.

Ireland’s Eye MonasteryEarly site; besieged 897; plundered 960

Killiney MonasteryEarly Gaelkc nuns

Killininny MonasteryEarly Gaelic nuns

Kilmainham MonasteryEarly site founded 7th century by St Magnet or Magdnend/Magnen in the time of St. Fursey. It was established as a Knights Hospitaller site in 1174 by Strongbow.

Kilnamanagh MonasteryEarly site

Kinsaley MonasteryEarly site founded by St. garden (Gobban) or St. Doulagh

Lambay Island Monastery Early site founded by St. Colmcille

Lusk AbbeyEarly site founded about 450 by Cuinnidh mac Cathmugh (St. MacCullin), plundered by Danes 827, 856, burned by Munstermen 1053; by Meath men 1133.

Newcastle MonasteryEarly site founded by St. Finnian

Rathmichael MonasteryEarly site has remains of round tower

Saggart MonasteryEarly site

St. Anne’s MonasteryEarly site founded by Bishop Sanctain ?

St. Doolagh’s MonasteryEarly site founded by St. Doolagh?

St. Patrick’s Island Monastery Early site founded by St. Patrick, burned by Danes in 798, became Augustinian Cannot Regular after 1140

Santry MonasteryEarly site founded in 6th century

Sruthair MonasteryEarly site possibly located in Co. Dublin

Swords MonasteryEarly site founded about 560 by St. Columbkill

Tallaght MonasteryEarly site founded by St. Maelruan; plundered by Danes in 811, may have ceased after 1125

Taney MonasteryEarly site.

Tullow/Tully MonasteryEarly site related to St. Brigid and known as the “Hill of the bishops”.

Dublin was established as a diocese initially in 1028 by Sigtrygg (Sitric) Sildbeard, King of Dublin. At that time Dublin was subject to the Province of Canterbury. This was not confirmed bye the Synod of Rath Breasail.

At the Synod of Rath Breasail, held in 1111 CE, the Irish church was reformed from a monastic to a diocesan and parish based church. At that time diocese were established for the whole of Ireland. Dublin, that had been a diocese under Canterbury, was not named as a diocese. It was not until 1152, at the Synod of Kells that Dublin was not only established as a diocese but was also given the distinction of being named a Province. The Archbishop of Dublin had jurisdiction over Ferns, Glendalough, Kildare, Leighlin and Ossory. This was the state of affairs at the turn of the 13th century.

Clondalkin

Christianity arrived in East Leinster in the 5th century. It was not until the 7th century that an abbey was established at Clondalkin by St. Cronan who was also known as Mocha. He died in 630.

Norsemen attacked the abbey in 832, 1071 and 1076. They settled in the area and constructed a fortress called Dun Amhlaeibh after their king.

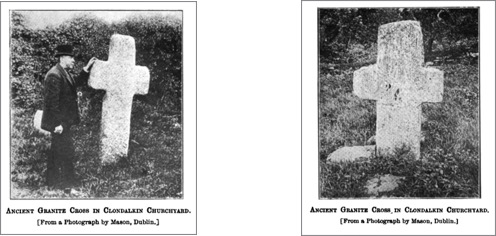

In the present churchyard of St. John’s Church there are a font and two granite crosses that Sherlock presumed to be ancient. (Sherlock p. 4) The crosses are listed by Crawford but not by Harbison. There is also a round tower nearby that may have been constructed as early as 700.

The Annals of the Four Masters lists St. Cronan Mocha as the first abbot of the abbey. Saint Ferfugillus, is named as the first bishop, died 789 and Cathal who died in 879 is also mentioned as a bishop. (Sherlock p. 4)

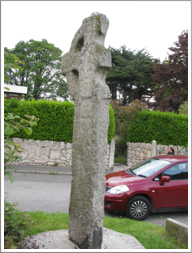

Ball, writing in 1899 tells us that “In the churchyard there is a large cross of granite without ornament, 9 feet in height, and made of a single stone; also a small one, apparently much older, and a curious font, of great size, made of rough granite.” (Ball, p. 97) In the photos above the larger cross is on the left and does not measure 9 feet (2.7m) in height. Crawford listed its height as 6 feet (1.8m). (Crawford p. 219) The shorter of the crosses is pictured to the right. It also appears to be without ornament. Both photos above are from Sherlock. The photos below show the larger cross. Both crosses are located behind the church. It was necessary to scale the wall, which was not a difficult task, in order to get into the church yard.

The larger cross, seen left and right has no decoration.

The photos left and right show the smaller cross. In the center of the cross on the side shown to the left, there is an equal armed cross enclosed within a ring. This cross within the cross has a partial shaft carved that becomes less pronounced as it descends down the shaft.

On the side of the cross shown to the right there is a carving of a cross that has arms that reach into the arms of the main cross. The upper arm is broken off and the shaft of this carved cross within the cross extends to the base of the shaft.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 36 3 E. Clondalkin is located west of the M50. Take exit 9 onto the N7 west. Exit right on the R113 to the northwest. Take a right on Convent Road. Stay left at the Y and continue on Tower Road. The Round Tower will be obvious on your left, St. John’s Church will be on your right. The crosses are in the churchyard behind the church. You may have to climb over the low wall to get to them. On the map to the right the round white circle marks the round tower.

The map detail left is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Resources Consulted

Ball, F. Elrington, “Descriptive Sketch of Clondalkin, Tallaght, and Other Places in West County Dublin”, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 9, No. 2 (Jun. 30, 1899), pp. 93-108

Sherlock, Canon, “Clondalkin”, Journal of the Co. Kildare Archaeological Society and Surrounding Districts, Vol. V. 1906-1908, Dublin, 1908, pp. 3-11.

Finglas Cross

The Site:

The Celtic abbey of Finglas is associated with Saint Canice or Cainnech, who lived from about 515/16 to about 600. The monastery was founded about 560 and was active in from the 6th century until at least the 9th century. Five Saints have been associated with Finglas: St. Flann, St. Noe, St. Dubhlitir and St. Faelchu. Dubhlitir appears to have been abbot and was succeeded by Flann who was described as a bishop, scribe and anchorite. The end of the abbey may have come at the hands of the norsemen who destroyed it. Afterward it drops from the records. (Tutty, pp. 66, 67)

Finglas, along with Tallaght and Terryglass, was associated with the Celi De movement. (Harbison, 1992, p. 330) This movement seems to have originated in Ireland near the end of the eighth century. (Zimmer, p. 100) Celi De referred to those who had dedicated themselves to the service of God.

In 1649 Cromwell’s soldiers passed through the area and knocked down the great cross at Finglas, breaking it in two parts. Tradition says that locals buried the cross to protect it from further damage. In 1816 it was unearthed due to the interest of Rev. Robert Walsh. It was re-erected near where it was found. (Tutty, p. 67)

The Cross

This cross originally stood north of the village at Watery Lane but since 1806 or 1816 it has stood inside the entrance to the local graveyard. It stands on a base that is about 39 inches (1m) tall. The cross itself is 7 feet (2.16m) high 5 feet (1.55m) across the arms and 10+ inches (27cm) thick.

Harbison groups this cross with the “South Leinster group of granite crosses” and suggests that these crosses postdate that at Moone which could be dated as early as the second quarter of the 9th century. (Harbison, 1992, pp. 376-7) The descriptions below are based on Harbison, 1992, p. 90) The cemetery is typically locked but the caretaker lives in the last house before walking up to the cemetery gate.

East Face:

A cross stands out in relief with a ring formed by two ribs that cross over the shaft and arms. A roundel is at the center and the decoration is not discernible. There was other sculpture on this face that is also too worn to identify. The arms outside the ring are smaller than those inside.

South Side:

Under the ring is an S-shape, probably of animal nature. Under the south arm is another S-shaped animal “with legs pointing forward and seen from above.”

West Face:

Only the outline of a cross and the ring are visible.

North Side:

There is a long S-spiral on the underside of the ring and under the arm is a diamond shape design.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 36 3 F. Located inside the M50. Take M50 exit 5 to the southeast on the R135. About 200m after you cross the R103 take a right on Wellmount. There is a cemetery visible up the hill to the right. The cross is just inside the gate off Wellmount.. The gates are typically locked but the caretaker lives in the last house before going up the steps to the gate.

The map to the right is cropped from the Historical Environment Viewer.

Resources Consulted

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Tutty, Michael J., “Finglas”, Dublin Historical Record, Vol. 26, No. 2 (Mar. 1973), pp. 66-73.

Zimmer, Heinrich, The Celtic Church in Britain and Ireland, Translated by A. Meyer, London, 1902. http://www.thechristianidentityforum.net/downloads/Celtic-Church.pdf

Jamestown Cross

Jamestown is not an ancient designation. It appeared only during the 16th century. Aside from O’Reilly there seems to be little information about the cross there. It is listed by Crawford who describes it as “A rude cross, 3 feet 6 inches (1+m) high, with a large figure in relief on the west side, and the remains of a raised circle on the east side.” (Crawford, p. 220) O’Reilly suggests that the cross seems to be a “votive monument” and if it was actually dedicated to St. James it may date from the 9th century or before. (O’Reilly, P. 254)

The site near the cross was part of an ancient cemetery. This suggested to O’Reilly that the church of Balemochain, the vanished church of Ballyogan may have been on this site. That could date the site to the late 6th century. (O’Reilly, p. 258)

Located near St. James’s Well is a “curious cross” that stands four feet high and two feet wide. In the center of the northeast face a single circle is carved in high relief. On the opposite face there is a rude human figure, also carved in high relief. The head is in the center of the cross with the body occupying the shaft. “There is no attempt to represent a neck; raised mouldings diverging from the head in rounded curves form the shoulders, and, descending some distance along the outer edges of the shaft, represent the arms which turn inwards, the hands meeting, as in the Tully figure, below the centre of the breast.” (O’Reilly, p. 253)

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 36 4 F. From the M50 take exit 15 and go south on the R842. When it intersects with the R117 take a right. There will be a sign to the Stepaside Golf Course. Permission will be needed to access the site as it is in the middle of the course in a woods between two holes.

The map right is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

O’Reilly, Patrick J., “The Christian Sepulchral Leacs and Free-Standing Crosses of the Dublin Half-Barony of Rathdown”, the Journal of the royal Society of antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 31, No. 3, [Fifth Series. Vol. 11] (Sep. 30, 1901), pp. 246-258.

Crawford, Henry S., “A Descriptive List of the early Irish Crosses, Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 37 [Vol. 17 Fifth Series] 1907. p.220 pp. 187-239

Kilgobbin Cross

The Site

The history of the ecclesiastical foundation at Kilgobbin is uncertain. Some information suggests a date as late as 800 to 900. Other evidence suggests an earlier 7th century date.

Excavation work at the site suggests a date for a probable monastic foundation as early as 600. Most of the artifacts discovered date from 650 to 950 with a predominance toward the earlier period. This conclusion is also supported by the series of enclosures identified and the metallurgical evidence found. (Bolger, p. 103, 107)

The name of the site, Kilgobbin, may be of late origin (post Norman) but could also support an early date for the foundation as the name could refer to a Saint Gobban, a nephew to St. David of Wales. (Bolger, p. 87) However, “Local tradition associates the place-name with the mythological Goban Saor.” (Bolger p. 87) Goban Saor is associated with Goibniu or Gaibhne who was the smith of the Tuatha De Danann in the mythology of Ireland.

Control of this area prior to the Scandinavian control of Dublin was in the hands of the Ui Briuin Cualann. It then passed to the Kingdom of Dublin (9th century). The name Technabretnach or “house of the Welshman/men” was used by Archbishop Alen to refer to what is now Kilgobbin. John Alen (1476-1534) was Archbishop of Ireland and wrote the Liber Niger. The name Technabretnach may well relate to an influx of Welsh settlers into the area around Dublin with the support of the Scandinavian Kingdom of Dublin. (Bolger, p. 87)

The Crosses

There is a tall cross at Kilgobbin that is listed by Harbison. The description below is based on his description. Dating of the Tall Cross ranges from the 10th to the 12th century. In addition, Ó hÉailidhe discusses a cross-head fragment found inside the church.

The Tall Cross: This cross is made of granite and stands about 8 feet (2.4m) in height and was nearly 4 feet (1.2m) across the arms. There are roll mouldings on the edges of the shaft and the sides are undecorated.

East Face: The Crucified  Jesus is depicted clad in a long robe and with arms outstretched on the arms of the cross.

Jesus is depicted clad in a long robe and with arms outstretched on the arms of the cross.

West Face: (?) The Risen Christ. The figure of Christ is similar to that on the east face but the arms are shortened. It could represent either the Risen Christ or Christ in Glory. (Harbison, 1992, p. 117; photo right Vol. 2, Fig. 382)

The sides of the cross have no carving. Seen to the left is the south side and to the right the north side with the ruins of a church on the hill behind.

Cross-Head Fragment

A fragment of a cross-head was found inside the church but is no longer present there. The date is uncertain. The granite fragment measures 7 inches (18cm) by 7 inches (18cm) by 3.5 inches (9cm) thick. It had a circular panel in the center and the arms appear to have been short. “On one face the centre panel is framed by an incised line and raised border. On the other face there is a raised border and one arc of a cross drawn with arcs in relief.” (Ó hÉailidhe, p. 144; illustration p. 143)

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 36 4 F. From the M50 take exit 15 and go south on the R842. When it intersects with the R117 take a right. Follow the R117 past Stepaside and take the Kilgobbin Road to the right The cross will be on your right about 200m along. If you come to a three way roundabout you have gone too far by less than 60m. The cross is marked by the upper black circle of the cluster, the ruins of a church are above it on the hill.

The map to the right is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Bolger, Teresa, “Excavations at Kilgobbin Church, Co. Dublin”, The Journal of Irish Archaeology, Vol. 17 (2008), pp. 85-112

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

O’hEailidhe, P., “Decorated Stones at Kilgobbin, County Dublin”, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 114 (1984), pp. 142-144

Kilmainham Cross

The Site and Saint

By about the year 607 there was a monastery at what is now Kilmainham and St. Magnend or Magnen was the abbot. The early name of the place was Kill Magnend or the church of Magnend.

In 782 the death of “Leargus Ua Fidhchain, a wise man of Cill Maighnenn.” (Annals of the Four Masters)

In 1013 and again in 1014 Brian Boru and his army were encamped at Kilmainham. In 1013 he was there from August to December, but there was no major action. In 1014 Brian was encamped at Kilmainham prior to the battle of Clontarf. Both Brian and his son Murrough were killed in the battle and its aftermath. Murrough is said to have been buried near the cross that stands in the present graveyard.

A little over a century and a half later, Strongbow established a priory at Kilmainham for the Knights Templars who presided there at the end of the High Cross period in 1200.

The site of the old monastery and of the priory of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem was later the royal Hospital Kilmainham. It now houses the Irish Museum of Modern Art.

The Cross

The cross is carved of Granite. The shaft that remains is just short of 10 feet (3m) in height, just over 2 feet (61cm) wide and one foot (30cm) thick. It stands in a granite base. The descriptions below are from Harbison, 1992, p. 130.

East Face: The carving on this face of the cross is difficult to discern. Harbison described it as follows: “The east face has a sunken panel, the bottom of which is about 1.13m above the base. It contains a vertical rib in relief which opens out into a spiral on either side below, and expands into a V-shape at the top.” The photo to the left is from Harbison, 1992, vol. 2, fig. 435.

West Face: There is a sunken panel on this face as well. It contains an interlace that ends in “two pendants with circular ‘bosses’ at the bottom.” The illustration to the right is from the Dublin Penny Journal, Aug. 25, 1832, p. 68.

Sides: Once again there are sunken panels but no apparent decoration.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 36 3 F. The Royal Hospital, Kilmainham is located just to the south and west of Heuston Station in Dublin. It is just south of St. John’s Road West (R148). The cross is in a locked cemetery at the far west end of the grounds. See the map to the right. Entry is by special arrangement with the curators. The map to the right is cropped from Googlemaps.com.

Sources Consulted

"Annals of the Four Masters", CELT, Corpus of Electronic Texts, http://www.ucc.ie/celt/publishd.html,

Dublin Penny Journal, Aug. 25, 1832, p. 68.

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Tully Church, (Laughanstown) Crosses

The Site

The church at Tully is pre-Norman with a 13th century chancel. There are two crosses on the site and three grave-slabs. The site was once known as tulach na n-Epscop or the “hill of the bishops”. The name derives from a passage in the Martyrology of Oengus that tells of 8 bishops departing from Tully to visit St. Brigit at Kildare. Tully has a strong connection with Brigit while many south Dublin churches were associated with St. Kevin of Glendalough. It has been speculated that the church was founded in the 8th century.

In the pre-Norman period the church lands were “granted to Dublin’s Holy Trinity Church (Christ Church) by Citric Mac Torcaill, a member of the ruling Viking family of Dublin.” (Corlett and Condit)

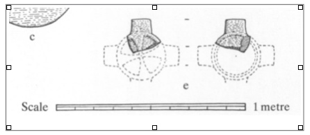

The Crosses

There are two stone high crosses at Tully. The first is a ringed cross that stands on a high plinth. This plinth was constructed when roadwork was done after 1860 to keep the cross at its original elevation. The cross and base are both granite. The cross stands about 7 feet (2m) in height. The top of the cross has the shape of a gable roof and the carving of shingles is very clear, but there is no other decoration visible on the cross. This cross has been dated to the 10th century.

In the photo to the left the west face and the north side are visible. In the photo to the right the east face and south side are visible.

The second cross stands on a tall base nearby. It stands about 7 feet (2m) in height and one arm has broken away. “On the west face is a weathered carved head at the intersection of the cross. On the east face is a figure carved in relief, with its head placed at the intersection of the cross. The figure is depicted with a long beard, but the facial features are worn away.” (Corlett and Condit) This figure holds a crosier and so represents a bishop. Corbett and Condit propose that his figure may represent Lorcan Ua Tuathail (Lawrence O’Toole). The photo to the left shows the cross in context as seen from the northeast.

The second cross stands on a tall base nearby. It stands about 7 feet (2m) in height and one arm has broken away. “On the west face is a weathered carved head at the intersection of the cross. On the east face is a figure carved in relief, with its head placed at the intersection of the cross. The figure is depicted with a long beard, but the facial features are worn away.” (Corlett and Condit) This figure holds a crosier and so represents a bishop. Corbett and Condit propose that his figure may represent Lorcan Ua Tuathail (Lawrence O’Toole). The photo to the left shows the cross in context as seen from the northeast.

In 1901 O’Reilly described this same carving as “a full-length and well-proportioned female figure” and suggested it might represent St. Brigit. (O’Reilly, p. 249) More recent consensus agrees with Corlett and Condit in identifying a beard on the face of the figure, making it the face of a male.

This cross has been dated to the 12th century and is not included in Harbison’s “The High Crosses of Ireland”.

The photo to the left shows the cross from the northeast. The photo to the right shows the cross from the southwest.

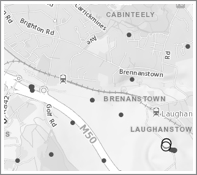

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 36 4 G. From the M50 take exit 15. If you are going south take the road opposite the exit at the first round-about. At the second round-about take the first exit to the left (Glenamuck Road North. At the first major intersection (Brighton Road) take a right and follow Brighton until it takes a sharp left turn. After the turn, about 100 yards later take a right (Lehaunstown Road) and follow it as it winds about till you see the ringed cross on the left. If you are going north on the M50 you will take the exit three quarters around the round-about (Glenamuck Road North) then follow the directions above.

The map to the right is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Corlett, Christiaan and Condit Emer, Heritage Guide No. 61: Tully church, Laughanstown, Co. Dublin, Archaeology Ireland, June 2013.

Corlett, Christiaan, http://www.christiaancorlett.com/blog/4564514201/Tully-Church-near-Cabinteely-south-county-Dublin/5971049.

National Museum Cross Fragments

Fragments of eight crosses, not original to County Dublin, are to be found in the possession of the National Museum in Dublin. In the spring of 2018 I had the opportunity to view and photograph these fragments, only two of which are on display in the museum. In addition a possible cross base of unknown provenance is described.

These cross fragments are listed in the National Monument Viewer under the headings, Dublin and High Cross (present location). See http://webgis.archaeology.ie/historicenvironment/. Where there is a difference between the measurements in inches and that in centimetres, the measurement in centimetres reflects measurements taken by Harbison.

Each fragment has an identification number. All are located in the Townland of Dublin South or at the National Museum Resource Centre at Swords. The descriptions follow.

DU018-181—- The shaft of the high cross the base of which stands in the graveyard at Drumcliff, Co. Sligo (SL008-084008) There are two sections of the cross-shaft, joined by a modern concrete filler. Only one face of the cross is visible as it is displayed standing against a wall. See the photo to the right.

The lower fragment measures 22.5 inches high (60 cm), 14.5 inches across (34 cm), and 9 inches thick (22.5 cm).

East Face: See the photo to the left. At the bottom of the shaft is a narrow plinth with an empty panel. It is set off by double roll-moulding. Above this there is a pattern of interlace that has four circular motifs that are interconnected. In the center there is a cruciform pattern crossed by strands of the interlace that connect the panels diagonally.

The panel at the top of this fragment is broken, making identification of the image there difficult. Harbison identified the image as David Slaying the Lion. He wrote: “The animal’s body and feet are visible, one of the front legs being raised. David’s right knee is visible on the lion’s back, while the lower part of the left foot can be seen beneath the front part of the lion’s body.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 73)

The Sides: On the right or north side there is a plinth and two panels, both undecorated. The panels have double roll-moulding. See the photo to the left. The left or south side has a plinth. Above this is a semi-circle then an undecorated panel with concave ends. Above this is a circle and the lower end of another apparently concave panel. See the photo to the right. (Harbison, 1992, p. 73 and Vol. 2, Fig. 223)

West Face: There is no clearly defined plinth. The lower panel has an interlace design similar to that on the east face. The panel above is broken. In the panel are the lower torsos of three figures, each clothed in a long robe. While a number of possibilities exist for explaining the meaning, there is not enough of the panel to provide any context. See the photo to the left. (Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 224)

The upper fragment measures 32 inches in height (83 cm) and tapers to 10.25 inches near the top (30 cm in the middle of the fragment). It is 6.5 inches (16.5 cm) thick. There are two panels on the shaft with part of another panel forming the lower part of the head of the cross. There is an indication on the right side at the top of the shaft that there was probably a ring on the cross.

East Face: See the photo to the right. The lower panel represents Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac. There are two persons depicted. The left hand person is as tall as the panel and holds a club or some other weapon in his right hand. The right hand figure is smaller and appears to lean forward toward the left hand figure. He may be depositing a bundle of faggots on the altar. Above to the right, appearing to be on the back of the right hand figure is a sheep or ram. In the extreme upper right corner is a circle or boss that may represent the angel.

The upper panel contains an image of Daniel in the Lion’s Den. Daniel stands in the center of the panel with arms outstretched. On each side of Daniel there is a lion below and above his arms.

In the constriction of the arms there is the lower part of a figure that appears to be clothed to the knees. There is not enough context to hazard a guess as to the identity of this image.

The Sides: The South side has two panels too worn to identify any patterns. The North side appears to have two undecorated panels.

West Face: See the photo to the left. (Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 228) There are two panels on the shaft with another in the constriction of the arms. Harbison identifies the lower panel as an image of the Resurrection. Christ in the center is flanked by angels, one of which holds a staff of some sort. Below, on both sides of Christ’s feet there is a sleeping soldier with his weapon on his shoulder.

The upper panel has been identified as a Mocking of Jesus scene. Jesus, the central figure is flanked on each side by a figure taken to be a soldier. Each holds a stick or baton up to Jesus’ face.

In the constriction of the arms there is a knot of interlace. A pair of feet are above this but there is no context to venture a guess as to the identification.

DU018-190—- “Fragments of a possible high cross that originally came from Clonmacnoise, County Offaly (see OF005-064—-). Described by Harbison as ‘In the National Museum in Dublin there are some fitting sandstone fragments from Clonmacnoise. The top of the upper fragment is so damaged that it is difficult to know whether it formed part of a pillar or cross. Together, the fragments measure about 90cm (35 inches) in height, and they are 35cm (14 inches) wide and 18cm (7 inches) thick. Their edges have been damaged, and the panels are framed by a raised moulding. There is a large tenon at the bottom, but no trace of a mortise hole on top. Only one face is decorated suggesting that it may have originally stood against a wall.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 57) In the photo below the left end is the lower end of the shaft.

Main Face: "Three deeply carved pelta motifs one above the other and rising from a double raised moulding below. At each end they roll into a three-coil spiral terminating in pierced lobes. There is a ‘drop’ appended to the centre of the pelta, which is formed of two facing trumpet-ends, above which there is a three pointed interlace.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 57)

Left Side: A panel of interlace. This side was against a wall when I visited it. The photo below is taken from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, fig. 169.

Right Side: "A vertical panel divided into three sections. In the centre there is an interlace. Above and below it there are two sunken crosses surrounded by a stepped raised moulding, outside which there is a further stepped moulding with a square in the outer corners." (Harbison, 1992, vol. 1, 57). The photo below shows this side of the shaft.

DU018-191—-There is a cross fragment (OF009-005006-) cemented into the S end of the W wall of the graveyard at Clonmacnoise, Co. Offaly (OF990-005009) and this piece appears to have come from the shaft of a high cross: it has interlace decoration on its visible side. The missing cross head described below and the possible fragment of the shaft may belong to the same cross. This cross-head is now housed in Dublin, in the National Museum of Ireland (IA File, IA/29/1988). The cross-head is on display in the museum.

In 1974 the head of a high cross was removed from the monastery at Durrow and was described by Harbison as "A cross-head of sandstone stood for centuries on top of the gable of the now disused Protestant church to the east of the main cross. It fell to the ground in the late 1950s, after which it was placed on a base just south of the church. In 1974 it was, apparently, removed to Durrow Abbey nearby, in the grounds of which the old monastic site lies. The cross-head is 43cm (17 inches) high, 68cm (27 inches) across the arms, and the lower part of the shaft has a maximum width of about 20cm (8 inches) The arms expand markedly at the terminals, and it seems unlikely that the cross originally had a ring. The ends of the arms are probably not decorated.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 82)

East Face: (?) David as Shepherd. "A figure stands with a crook in its left hand, and there may be a sheep with turned-back head to the right. Above the figure’s head there is what is probably an angel, on the analogy of panel S 3 of the Cross of the Scriptures at Clonmacnois. The figure is most likely to represent David as Shepherd, the presence of David in such a position at the centre of the cross-head being rendered quite likely in view of the David interpretation suggested here for the scene at the centre of head of the Tall Cross at Monasterboice. The arms are decorated with interlace.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 83)

West Face: The Crucifixion. "Christ is shown in a tight-fitting garment, stretching his arms out at right angles. Stephaton and Longinus are indicated as busts beneath Christ’s arms, though their attributes are not shown. At the end of the arms there is a whirl from which serpent headed animals emerge. Above Christ’s head, a bird flies upwards to the left." (Harbison, 1992, vol. 1, 82-3)

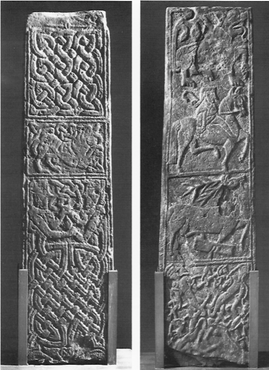

DU018-205—-. The high cross from Kylebeg or Banagher, Co. Offaly (OF021-003004-). Described by Harbison as "A cross shaft of sandstone which originally stood at Banagher, Co. Offaly, was removed by Cooke around the middle of the last century (1800’s). After his death, it was moved to Clonmacnois around 1870, and to the National Museum in Dublin in 1929, where it is now on display with the inventory number 1929:1497. It is 1.47m tall, and its tapering faces and sides have maximum dimensions of 40cm and 19cm respectively. All the corners have small roll moulding, and the panels which are all of different sizes are also framed by similar moulding. Damage to the two top side panels was probably caused by a secondary attempt to add a ring. A shallow mortise-hole on top is probably secondary also.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 25)

The shaft fragment stands 56.5 inches in height (143.5 cm) has a width of 14.5 inches (39 cm) and is 7 inches thick (18 cm).

Face 1 - Harbison identifies the face pictured to the left as face 1. Below right are Harbison’s photos of both faces. (Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Figs. 65-66)

Panel 1: "Emerging from a single-strand interlace between two animals with backward-turning heads at the bottom of the panel is a two-strand interlace. The top of this interlace coalesces with two figures in profile. The right hand of the left-hand figure grasps the other’s left wrist, and their respective other hands seem to touch. The two figures — with their spiky noses - have hair which forms an interlace between their heads.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 25)

Panel 2: "A crouching lion with protruding tongue and with its tail between its legs. There is a three-point interlace in the upper left hand corner and another very irregular, interlace above the lion’s back.” (Harbison, 1992, pp. 25-26)

Panel 3: A two-strand interlace.

Side 1 - Harbison identifies the side pictured in the two photos to the right below as Side 1. The photos to the left below show both sides of the cross shaft. (Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Figs. 67-68.)

Panel 1: "Two animals one above the other, enmeshed in a narrow band of interlace. The tail of the upper animal terminates in a triangular shape in the centre of the panel.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 26)

Panel 2: A single-strand interlace.

Panel 3: "Interlinking C-shaped spirals forming pelta-shapes, terminating in two outward turning spirals at the top.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 26)

Panel 4: "A damaged coiled animal (head missing) with a fish-like tail.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 26)

Face 2 - Harbison identifies the face shown to the left as Face 2. For his photo see Face 1 above right.

Panel 1: "A human interlace with the legs intertwined at the centre and the bodies radiating outwards to the corners. A narrow ribbon winds its way around the arms of the four human figures. The heads of these figures are located in the corners of the panel. The bodies are narrow and sinuous.

Panel 2: "A deer with its front right leg caught in a rectangular trap.

Panel 3: "A horseman, with hair flat on top and falling to a curl behind, holds a crozier in his right hand which emerges from the folds of his cape-like garment. He has no stirrups, and his legs are placed well forward as the horse prances proudly to the right. Above is a partially-damaged prancing lion with protruding tongue, also facing towards the right. Its tail rises behind, and terminates in two leaf-like shapes.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 26)

Side 2 - Harbison identifies the side shown in the photos to the left and right as side two. For Harbison’s photo see above under Side 1.

Panel 1: "A tall panel bearing interlace of various kinds which terminate in animal-heads with ropes-like necks and ear-lappets, and with their mouths biting the interlace.

Panel 2: "Very similar to panel 3 on side 1.

Panel 3: "Interlace terminating below in animal-heads which bit the interlace. A broad groove at the top suggests that a ring may have been inserted secondarily to support the arms of a cross." (Harbison, 1992, vol. 1, 25-26)

DU018-210—: Ogulla, Co. Roscommon is the original location of the head of a high cross. Harbison suggests that it probably dates to the 12th century. (Harbison, 1992, p. 185) The fragment consists of the crux or crossing in the head of the cross. It measures 20 inches (51 cm) across what would have been the arms, 14.5 inches (37 cm) in height and 4.75 inches (12 cm) thick. The thickness does not include the boss on one face and the head and shoulders on the other that stand out from the face of the stone.

Face 1 (pictured below left) has a large boss that is surrounded by a dental pattern.

Face 2 (pictured below right) contains a figure with head and shoulders that is suggestive of the crucifixion of Jesus.

There is a mortise in the base of the peice (see the photo below) that seems unusual for a fragment that appears to have been only a portion of the center of the head. Presumably the body of Jesus would have extended onto the shaft of the cross in the manner of the 12th century cross at Dysert O Day in County Clare.

Balsitric ME006-033001- The head of a cross with an imperforate ring. The cross-head measures 11.25 inches (28.6 cm) in height by 11 inches (28 cm) across the arms. The fragment is about 2 inches (5 cm) thick. The cross was found in the ploughing of a field known as “the Church field”. It was located within the old ecclesiastical enclosure. (Michael Moore, Historic Environment Viewer)

Face 1: On the face pictured to the left below there is the shape of an equal armed cross and there is a low boss in the center of the head.

Face 2: On the face pictured to the right below there is a crucifixion scene. The arms of Jesus are angled down. Harbison notes that there may be a boss on each arm and there could also be something above Jesus’ head. (Harbison, 1992, p. 25)

Donaghmore cross-head ME025-015004- It is unclear whether this fragment is from Donaghmore in County Down or County Tyrone. The damaged head of a sandstone high cross 25 inches (0.63m) high ; 14 inches (original c. 0.45m) across the arms and 4.25 inches thick (10.8 cm), now in the National Museum of Ireland, is almost certainly that described by Wilde (1857, 1, 141-2) as being from Donaghmore. It has roll mouldings, the shaft was divided into panels, and interlace is confined to a knot at the crux and on the ring (Harbison 1992, 185)

The photo to the left shows the face that Harbison refers to as Face 1. There is vertical interlace running from the center of the head down. The low end of the fragment has the suggestion of a panel set off by roll-moulding. The arm may contain a three cornered interlace. At the top of the head is a human figure with arms raised in an orant pose and feet standing on the interlace that is in the center of the head.

The photo to the right shows the face that Harbison refers to as Face 2. There is no clear carving visible. At the top it is clear that the ring was denoted by indentations that also appear to produce the rough shape of a cross in the center of the head.

Killary, County Meath, inventory nos. 1987:156-157; 1987 156, 1987 157.

These two fragments are assumed to have been parts of the same cross shaft. They were re-used in the 16th century as window stones.

Fragment 1 (pictured to the left)

This fragment measures 55 cm (23 inches) high, 22.5 cm (9 inches) broad and 15 cm (6 inches) thick.

Lower Panel: At the bottom of the panel is a human head above six bosses. Harbison suggests that using the Arboe cross W 3 panel this could represent the Multiplication of the Loaves and Fishes. Above this there is a figure seated on a chair. The body is in profile but the face is turned toward the viewer. This figure seems to face another figure on the missing half of the shaft. There is not enough context to offer any identification of this image.

Upper Panel: The lower part of a body shows us the legs and lower torso. In the right hand there appears to be a “hooked or U-shaped object visible at thigh level.” (Harbison 1992, p. 126) This figure originally faced a fragmentary figure to the right. By comparison with Muiredach’s Cross at Monasterboice, Harbison suggests this may represent the Traditio Clavium scene.

Fragment 2: (pictured to the right)

This fragment measures 50 cm (20 inches) high, 19.5 cm (8 inches) wide and 12.5 cm (5 inches) deep.

Lower Panel: There are eight joined knots of interlace above an unidentified object at the bottom that may have been part of a lower panel.

Upper Panel: There is a carving that Harbison suggests may be animal ornament. (Harbison, 1992, p. 126)

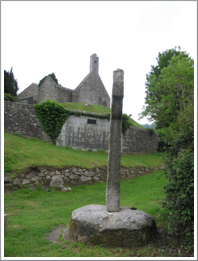

A Possible Cross Base (provenance unknown). Registration number 1994:26

This base is unusual in the sense that it has eight faces, each corner being cut into a narrow face.

This base is unusual in the sense that it has eight faces, each corner being cut into a narrow face.

Banager, County Offaly fragment.

Inis Cealtra, County Clare, Head fragment

Monasterboice, County Louth shaft fragment.

Monasterboice, County Louth head fragment

Mona Incha, County Tipperary, fragment