Two crosses are known from County Mayo. One is the lost cross of Cong. The other is at Mayo Abbey. The location of County Mayo is indicated by the red star on the map to the right.

Historical Background

The present County Mayo was established about 1570. The name derived from a famous monastery and the later diocese. The name Maigh Eo, means “plain of the yew-trees.” The ancient monastery is now known as Mayo Abbey. (Mayo History)

The Mesolithic and Neolithic Ages (4500 to 2500 BCE)

Human habitation in what is now County Mayo began as early as 4500

BCE, during the late Mesolithic Age. Archaeological surveys on the north coast in the area of the Ceide Fields complex document the development of a vast field system in the area. During this period megalithic tombs and stone circles were common. (County Mayo)

The Bronze Age (2500 to 500 BCE)

Metal work in bronze gives this period of history its name. Archaeological features include megalithic tombs for burials that change gradually to wedge tomb and cist burials. Other features included stone alignments, stone circles and fulachta faidh (early cooking sites). (County Mayo)

The Iron Age (500 BCE to 400 CE)

The introduction of Iron work seems to have coincided with the arrival of the Celtic people and their language. Archaeological features include crannogs, promontory forts, ring forts and souterrains. It was also during this time that the Ogham alphabet appears and that the tales of the Ulster Cycle are supposed to have taken place. (County Mayo)

The Early Christian Period (400 to 1000 CE)

About 500 CE the Fir Domnann were one of the major tribal groups in what is now County Mayo. (Ireland’s History in Maps) The Fir Domnann existed in two locations in Ireland, one in Leinster, the other in Connacht. They are presented as a people who predate the arrival of the Celts. (Pender, p. 101) The Connacht Domnainn territory, as reflected in the Rootsweb map for 500, encompassed the greater parts of Counties Mayo and Sligo. (Pender p. 109)

During the 6th century two other tribal groups were moving into the east of the Fir Domnann area. These were the Luigne and Gaileanga who were a part of the larger Connachta.

In the 7th century the Fir Domnann were overshadowed by the Ui Fiachrach. This was a tribal group descended from Eochaidh Mugmedon, king of Connacht in the 4th century. One of his offspring, Fiachra established the Fiachrach, later known as the Fiachrach Muaide. They seem to have held power in northern County Mayo and in County Sligo. They continued to have influence through at least the 12th century. The Luigne and Gaileanga, mentioned above also continued to be active in the area of Mayo and Sligo. (Ireland’s History in Maps)

During this entire time, of course, the areas occupied by the Fir Domnann, the Ui Fiachrach, the Luigne and the Gaileanga were part of the province of Connacht that had its traditional ritual site at Cruachain Ai, near Rathcroghan in County Roscommon.

Ecclesiastic History

The Christian faith probably came to Ireland first through contact with Roman Britain. It may have been introduced by captives who were forced into slavery and or through the medium of trade in other commodities. That there were Christians present in Ireland by the early 5th century is suggested by the appointment in 431 of Palladiusto serve as minister to the Christians in Ireland. He was appointed by Pope Celestine. This mission was followed by the better known ministry of Patrick, also sent as a bishop to the Christians in Ireland.

Some of St. Patrick’s work was done in what is now County Mayo. Tradition states that Patrick spent 40 days and nights praying for the people of Ireland on Croagh Patrick. Over time a large number of monasteries were founded in what is now County Mayo. The following is a list of those what were founded prior to to about 1200. ( List of Monastic Houses in County Mayo)

Aghagower Abbey, early site, founded by St. Patrick, later

Aghamore Monastery, early site, founded by St. Patrick for Loam

Airne Monastery, early site, founded in the time of St. Patrick, 5th century

Balla Monastery, early site, founded c 637 by St. Mocha (Cronan)

Ballintubber Abbey, early site, founded in the time of St. Patrick, 5th century

Ballyhean Monastery, early site, founded in 5th century by St. Patrick

Burriscarra Abbey, early site

Cell Tog Monaster,y early site, founded 5th century by Cainnech, bishop and monk of St. Patrick

Church Island, Lough Carra, early site, founded by St. Finan

Cong Abbey, early site, founded 624 by Domnal

Crossmolina Priory, possible early site, 10th century, later Augustinian Canons Regular

Davaghkeiran Monastery, early site

Domnach-mor Monastery, early site founded 5th century by St. Patrick

Duvillaun Monastery, early site Anchorites

Errew Abbey, early site

Fochlud Monastery, early site nuns founded 5th century by St. Patrick

High Island Monastery, early site founded 7th century

Inishglora Monastery, early site nuns, founded c 577-583 by St. Brendan

Inishkea North, early site, founded 6th century by St. Colmcille?

Inishmaine Abbey, early site, founded 7th century by St. Cormac

Inishrobe Monastery, early site, founded 6th century by St. Colmcille?

Inishturk Monastery, early site, founded 7th century by St. Colman

Kilfinain Monastery, early site, founded by St. Finan Abbot of Rathen

Kilgharvan Monastery, early site, founded 7th century by St. Fechin of Fore

Killala Monastery, early site, founded 5th century by St. Patrick

Kilmaine Monastery, early site, founded 5th century by St. Patrick

Kilmore Monastery, early site

Kilmore-Moy Monastery, early site, founded 5th century

Kilroe Monastery, early site founded 5th century

Kinlough Monastery early site, founded c. 8th century

Lia na Manach, early site, possibly founded in 5th century by St. Patrick

Mayo Abbey, early site, Anglo-Saxon monks, founded c 671 by St Colman of Lindisfarne

Meelick Monastery, early site

Oughaval Monastery, early site, founded 6th century (?) by St. Colmcille

Partry Monastery, early site, founded 6th century (?) in time of St. Colmcille

St. Derivla’s Monastery, early monastery, founded 6th century (?) by St. Dairbhile

Shrule Monastery, early site

Turlough Monastery, early site, founded 5th century by St. Patrick

Ten of these monasteries are attributed to St. Patrick. One of these, the Aghamore Monastery, he is said to have founded for for Loam. This suggests he left Loam in charge. Two others are indicated as being founded in the time of St. Patrick but with no attribution to him. Yet another monastery, the Cell Tog Monastery, was founded by Cainnech, a bishop and monk of St. Patrick. This is a clear indication of the significant ministry work that St. Patrick carried on in Connacht in general and what is now County Mayo in particular.

Of these 38 early monasteries, only two have been reported to have fragments of high crosses. Of these, the Cong cross fragment has been lost. We have only drawings of this fragment. The other, the Mayo Abbey base and fragment were not in the abbey graveyard in 2019.

In 1111, the Synod of Rath Breasail was held with the purpose of bringing the Irish churches into conformity with the Roman diocesan and parish based system. While there is some debate about where the Synod of Rath Breasail was actually held, there was no representation from Connacht. The reform movement had not gained footing in Connacht by that time. Nevertheless, five diocese were established for Connacht. Two of these, Cong Abbey and Killala, both in present day County Mayo, were named as locations where a bishop would lead the churches.

Cong Cross

The Site and Saint

St. Fechin (Feichin) founded a monastery at Cong in 623-624. It became known as Conga Feichin or “Feichin’s neck”. The foundation was established with the patronage of King Domhnall Mac Aedh Mac Ainmire. St. Fechin died in 664 of the yellow plague. At some point following his death the monastery fell into decline and may have ceased to exist.

The record is unclear as it is recorded that the church that existed in 1114 was burned. When this church was established is unknown. In any event a new church was constructed by the Canons Regular of the Order of St. Augustine shortly afterward. This church was destroyed by Munstermen in 1137. Following this King Turlock Mor O’Connor built a new church.

Having royal patronage from the O’Connors, the monastery developed into a large monastery with as many as 3000 cenobites. The schools there included scholars in history, poetry, music sculpture and illumination of manuscripts. There were craftsmen in many of the arts. The existing ruins date from reconstruction carried out by Cathal Crovdearg O’Connor (Cathal of the Red-Wine Hand) in 1205.

The Cross

Unfortunately the cross-shaft that is supposed to have come from Cong has been lost. It was reported in 1867 by Sir William Wilde. The shaft was 23’ (58 cm) high and Wilde made the illustration that is pictured to the right. The image to the left illustrates the sides and faces of the fragment. The two sides had animal interlace. One face had interlace, the nature of the decoration on the other face is unclear. Harbison identifies this cross as probable 12th century, hence from the later manifestation of the monastery. (Harbison, 1992, p. 60, illustration Vol. 2, Fig. 178)

Getting There: The cross, as noted above has been lost.

Resources Consulted

Cong Tourism: http://www.congtourism.com/cngabbey.htm

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Irish Tourist Association Survey: http://www.mayolibrary.ie/en/LocalStudies/IrishTouristAssociationSurvey/CongandTheNeale/CongAbbey/PDFDocument,16111,en.pdf

mayo-ireland.com: http://www.mayo-ireland.ie/en/towns-villages/cong/history/cong-abbey.htm

Mayo Abbey Cross

The Site and Saint

In about the year 670, St. Colman of Lindesfarne, in Northumbria, founded a monastery at Mayo, in the west of Ireland. This was a direct result of the decision of the Synod of Whitby in 664 that favored the practices of the Roman church over those of the Celtic church. Coleman first returned from Whitby to the mother church at Iona and from there traveled to Innisboffin, an island off the west coast of County Galway. From Innisboffin he moved to the isolation of what became Mayo (Maigh Eo). Over time Mayo came to be called “Mayo of the Saxons” because it’s foundation was a result of a split between Irish and Saxon monks. St. Colman brought with him to Mayo half the relics of Lindisfarne.

Mayo is mentioned by Bede in his History of the English People, written in the 10th century. It was known as a center of learning and had students from Britain and Europe, including many Saxon nobles. The first Abbot of Mayo was St. Gerald, who became abbot in 670 the year of Mayo’s foundation.

The monastery had its share of trouble with the Vikings. It was raided in 783 and again in 805. In 818 Turgesius completely destroyed it, though clearly it was rebuilt.

By the year 1000, Mayo Abbey had an estimated population of 3000 with important links to Canterbury in England, and the Court of Charlemagne, the Holy Roman Emperor (768-814).

In 1152 Mayo became a diocese and remained so until being joined with Tuam in 1631.

The Cross

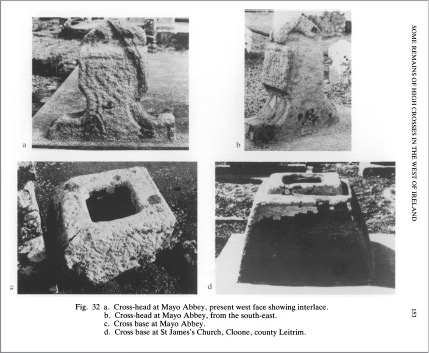

Cross-head: This fragment is set in a concrete plinth covering a grave in the graveyard of the old church in Mayo Abbey. It is 49.7cm high and 53.2cm at the transom. (Kelly, 1993, p. 154)

Decoration is difficult to assess. The arms of the cross are short. There is no evidence of a ring. The present west face may have been covered with interlace. There is also interlace on the south face of the upper shaft. On the other face is a sub-circular feature and a human head may be present above the modern base. There is a finial at the top of the shaft that is in the shape of a crouching animal straddling the cross-head from one narrow side to the other. This finial is unique among the Irish crosses. The presence of the finial, similar to St. John’s Cross at Iona suggests an early date for the cross, perhaps as early as 800. (Kelly 1993, pp. 152, 154)

The photos above right are from Kelly, 1994, p. 153.

Cross-base: The base is pyramidal in shape. It stands by the boundary wall of the graveyard, west of the old church. It is 34cm high and 64cm at the base. The base is also early in date but is not related to the cross-head. (Kelly, 1993, pp. 152, 154)

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 23, C3. The site indicated for the cross is located south of Mayo Abbey as indicated by the map to the right. Neither the cross-head or the cross-base were anywhere to be found.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Kelly, Dorothy, “Some Remains of High Crosses in the West of Ireland,” The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 123 (1993), pp. 152-163.

Mayo Abbey: http://www.mayoabbey.com

Mayo County Mayo: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayo,_County_Mayo

Museum of Mayo: http://www.museumsofmayo.com/mayoabbey1.htm