In general, the carvings on the crosses, where there are carvings, can be said to be either geometric designs, or figural representations. There is great variety in each of these two categories. This essay discusses geometric design.

Geometric Design

Henry S. Crawford identifies the following types of geometric patterns in Celtic art: spiral patterns, star patterns, interlaced patterns, fret patterns, and geometric symbols. (Crawford 1926)

Spiral Patterns: Crawford tells us that spiral patterns are of two types: C and S curves. Using these two types alone or in combination the artist can create an incredible number of different designs. (Crawford 1926, 12-19)

The left image above is a primitive pattern used in the Neolithic as well as Celtic periods of Irish history. The other three can all be found in the Book of Kells, a 9th century illuminated manuscript of the four Gospels. The infinite variety of design offered by the spiral patterns is clear from these examples. In all of these cases both C and S curves are easily identified. Spiral patterns were used in a variety of settings including as borders, in manuscripts, metalwork and carving. The left image above was found at boards.elsaelsa.com/topic/the-scorpio-search-... August 2010. The remaining three images found at www.stone-circles.org.uk/celtic/christian2.htm August 2010)

Spirals are generally recognized as one of the oldest of symbols. Whatever their original meaning, it was certainly spiritual in nature. These symbols are found in Neolithic sites around the world. The image to the left is the curb stone at the entry to the Newgrange Neolithic passage tomb, dating from about 3500 BCE. Above to the left the triple spiral is also found at Newgrange.

[Newgrange passage tomb, Co. Meath. Close-up of part of the passage stone. Image found at www.public-domain-image.com/miscellaneous/sli... August 2010]

A spiral has movement. We might think of a spiral as moving in toward or out from the center. Spiritually the center has often been thought of as the Holy, God, the Ground of our Being. As we spiral in, we move deeper into relationship with the Holy. As we spiral out we move from our divine source into service to others. The inward and outward dimensions of spirituality are in constant dynamic tension. Both are necessary to the spiritual journey. In Christian scripture, for example, we see this in the life of Jesus. He alternated time alone with God and time in service through teaching, healing, miracles, and so on. An excellent example of the spiral on a High Cross can be seen to the right. This cross is located at Killamere (Co. Kilkenny).

Star Patterns: Star patterns are created by the intersecting of curves or circles. They are limited in variety and Crawford tells us they are “a minor division of Celtic ornament.” (Crawford 1926 20) The modern design to the right is a tattoo.

Image found at startattoopictures.blogspot.com/2008/12/celti... August 2010

The star pattern is very rare on Irish High Crosses, appearing only twice according to Richardson and Scarry. (Richardson and Scarry 29-49) One of these is on the Decorated or West cross at Kilkieran (Co. Kilkenny). There are two stars on the north face of the base. The star patterns are located in the lower corners of the left side of the base, and are obscured by lichen and by wear. They are combined with other decoration, mostly interlace. The photo above left does not show the star patterns clearly, but it does serve to demonstrate just how worn many of the High Crosses are.

The other example is on a partial cross head at a site known variously as Ardane and Templeneiry (Co. Tipperary), photo right. Peter Harbison describes the central star as follows: “there is a marigold pattern in the centre, and the ring is decorated with interlocking angular ‘S-shapes’.” (Harbison 1992 volume 1, 19)

Interlaced Patterns: Crawford tells us that interlaced “patterns consist of bands crossing each other alternately over and under and present two principle classes – plaits and knots. In the plaits each band passes through the pattern from side to side before turning back, but in knotted patterns the bands frequently turn back in the body of the design.” (Crawford 1926, 23) The difference is clearly seen in the two book covers below. You will note that Cheryl Samuel, the writer and artist, uses the term cutwork rather than knotwork. Images found at ravenstail.com/store/dvd-booklets/ August 2010

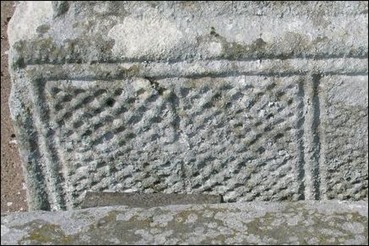

Plaitwork: Plaitwork in carving is almost certainly an imitation of weaving as can be clearly seen in the image on the left. It is found on some of the High Crosses, including the west cross at Kilkieran, (Co. Kilkenny) as seen in the photo below. This carving is on the south face of the base of the cross.

Plaitwork: Plaitwork in carving is almost certainly an imitation of weaving as can be clearly seen in the image on the left. It is found on some of the High Crosses, including the west cross at Kilkieran, (Co. Kilkenny) as seen in the photo below. This carving is on the south face of the base of the cross.

Knotwork: Celtic knotwork is related to plait work. In this case, however, the patterns have the potential for much greater variety. There are classes of knotwork based on the general shape of the piece. Crawford writes “Well marked classes are pointed, triangular and circular knotwork, the first and third of which are very characteristic of Irish monuments.” (Crawford 1926, 25) Peter Harbison describes the upper part of the shaft and the head of the South Cross at Ahenny (Co. Tipperary) right, as being decorated with “two-strand interlacing, regular on the shaft but more irregular on the head.” (Harbison 1992, 14)

The Meaning of Interlaced Patterns: Mildred Bundy reminds us that “The original iconographic meanings of Insular interlace patterns remain enigmatic.” (Bundy 197) She goes on to say that interpretations have varied widely including, “’a stylized representation of running water’, the river Jordan, an emblem of the Trinity, in the case of triquetra knots, as ‘a symbol of continuity’; and as an apotropaic or amuletic device.” (Bundy, 197) Each of these interpretations could certainly fit the interlaced carvings on Irish High Crosses.

Bundy suggests “Otto-Karl Werckmeister was closer to the mark in regarding intricate patterns, at least in religious contexts, as powerful tools to focus reflection upon the multiple layers of meaning in the text, as a guide for conduct, life, and salvation.” (Bundy 198) Werchmeister’s observation was made specifically in connection to illuminated Gospels where text and images are combined. In a way this could also be said of the scripture crosses that contain biblical images. But many of the Irish High Crosses have only abstract design. Here the patterns themselves may point to meanings such as those suggested above or to the interpretations of Derek Bryce, author of Symbolism of the Celtic Cross.

Two quotes from Bryce offer his perspective based on his research in mysticism and comparative religion. His primary thesis is that standing stones and crosses are symbols of the world-axis, the connection between Heaven and Earth. (Bryce p. 11) Concerning Plaitwork, he writes: “the basic symbolism is that of ‘the great cosmic loom of the universe,’ but it is important also to note that there are no loose ends, and the symbol is also one of continuity of the spirit throughout existence.” (Bryce p. 60)

The Celtic people of the Iron Age (beginning about 500 BCE in Ireland) and the early Christian era (beginning about 432 CE and ending with the arrival of the Normans in 1169 CE) certainly understood all aspects of life as interconnected. They had a sense of close relationship with the natural world, including plants, animals, earth, sky and water. They also looked beyond the artificial barrier of time. Past, present, and future were closely bound in eternity. In addition, the spirit world was experienced as very near. They may well have thought about interlace as symbolic of the seamless fabric of life as Bryce suggests.

Concerning knotwork, Bryce writes: “Here the symbolism is of the knots which bind the soul to the world. Like the Gordian knot cut by Alexander the Great, these knots must be cut or broken for the soul to become free to begin the spiritual journey.” (Bryce, p. 61) We find ourselves facing many knotty problems through the course of life. In some cases we can solve the puzzle and untie the knot. In other cases, like Alexander we may feel the need to cut ourselves free as Bryce suggests.

How did the Celtic people view these knots given their sense of harmony with the natural world? I offer another possible perspective on the knot. Celtic knots are complex and beautiful expressions of the connectedness of all things, and of the ever-twisting or ever-changing journey of life. With this understanding, the goal is not to break the knots but to trust in the unity of all life, to follow the path with the same confidence you would walk a labyrinth, knowing that the path leads inevitably to the center, to the Holy, to the Ground of our Being. In this interpretation, the journey is more important than the destination.

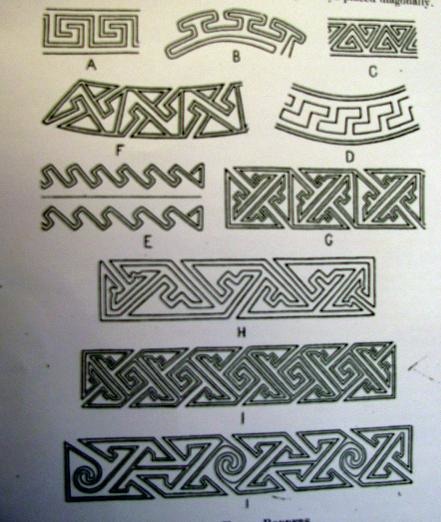

Fret work or Key-patterns: “The elementary form of the fret is a continuous line or band lying straight between certain points at which it is sharply bent in such a manner that no part crosses another.” (Crawford 1926, 34) In the image below are a number of illustrations Henry Crawford offers of the forms that fret work can take. (Crawford, 1926, 39) D-J are found on Irish High Crosses.

The image below, showing a section of the circle from the west face of the North Cross at Ahenny (Co. Tipperary) is described as “A key pattern of simple form which fills the segments of the ring. The space is divided into square compartments, in each of which is a pair of diagonal L-shaped keys springing from opposite angles and connected to the remaining angles by extra bars.” (Crawford 1926, 38)

Zoomorphic Designs: As the name suggests, zoomorphic designs have animals in them. Many designs can become zoomorphic by “modifying the terminal portions so as to represent the heads, feet, and tails of animals.” (Crawford 1926, 46) There is great variety in these images. Some depict fantastic representations of imaginary animals. Others depict real animals in a stylized way. On the left we have a panel from Muiredach's Cross at Monasterboice (County Louth), the south face. On the right we have a panel from the North Cross at Ahenny (County Tipperary), west face.

In the image on the left above, we have what Richardson and Scarry refer to as inhabited vine-scroll. (Richardson & Scarry 45) The base of the vine can be found in the center of the bottom of the design. The branches of the vine move upward and outward in sweeping spirals. In each of the six circles formed by the vine the branch terminates in the figure of a bird.

Crawford describes the design on the right above in this way: “A square panel of four men placed symmetrically with regard to the centre, and interlaced in a bold and effective manner… The idea of four human figures thus interlaced is an early and favourite one . . . It has been suggested that this close interlacing of human figures is intended to symbolize the brotherhood and interdependence of Mankind.” (Crawford 1926, 50)