This page explores the High Crosses of County Donegal. They include: Cardonagh, Carrowmore, Carrownaff or Cooley, Clonca Clontallagh, Fahan Mura, Inishkeel, Kilcashel, Ray and Tory Island. Where information is available there is a section on the history of the site, brief information about the primary saint related to the site and a description of the cross or crosses at the site. Except where noted, the photographs were taken by the author. Directions to the sites reference The Official Road Atlas Ireland. Maps of the sites are cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer. On the map to the right County Donegal is markled by a green star.

The story of County Donegal begins with the arrival of the Celts, who built forts around the countryside. These forts provided the Irish name of Donegal, Dun na nGall (Fort of the Foreigner), though this name was not used before the ninth century at the earliest. (Lacy, p. 30) From the second half of the sixth century the dominant political power lay in the hands of the Ui Neill, descendants of Niall Noigiallach, ‘Niall of the Nine Hostages’. “According to the Ui Neill myth, sometime around 429 to 432, that is before what was believed to have been the separate legendary date for the arrival of St Patrick in Ireland four of the sons of Niall Noigiallach are said to have conquered most of what is now Co. Donegal. Subsequently, they are said to have founded a number of dynastic kingdoms there. From Donegal, the influence of the people, their rule and eventually even their descendants, would spread eastwards and southwards into what are now the adjoining counties of Derry, Tyrone, Leitrim and Sligo.” (Lacy p. 31)

His descendants the Cenel Conaill controlled most of what is now County Donegal. The ancient name at that time was Tyrconnell or Tir Conaill, ‘the Land of Conal’. The Cenel Conaill were also influential in Christianity. Saint Columba or Columb Cille was of the Cenel Conaill. (Charles-Edwards, p. 441) Columb Cille is best known for founding a monastery at Iona in Scotland. Prior to leaving Ireland he founded monasteries at Derry at the southern tip of the Inishowen peninsula, home of the Cenel Conaill; Durrow in County Offaly; Kells in County Meath and Swords in County Dublin.

Carndonagh Cross or Churchland Quarters

The Site:

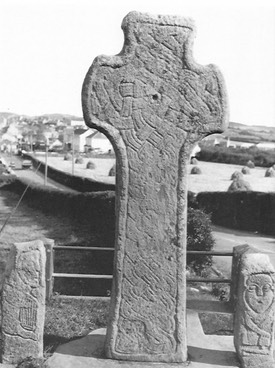

The high cross at Carndonagh is also known as the Donagh or St. Patrick’s Cross. It is located on the Inishowen Peninsula in County Donegal, see the photo to the right. This cross is part of a group of crosses that Peter Harbison identifies as the Northern or Ulster Group. The group includes crosses at Arboe, Armagh, Camus, Donaghmore/Tyrone, Galloon and others. (Harbison, 1992, p. 373)

In the Northern Group, Christ is typically shown wearing “a colobium-like garment which comes to just below the knees.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 274) In Roman usage, the colobium was typically a sleeveless tunic. This is true of the Carndonagh Cross, though the garment appears to have sleeves. The Carndonagh Cross is, however, different from many of the crosses in the group in having the crucifixion scene on the shaft of the cross rather than the head.

It is also typical of the Northern group of crosses for the two theives crucified with Jesus to be shown on the arms of the cross. With the crucifixion placed on the shaft of the cross that is not the case with the Carndonagh Cross. It is possible, however, that the theives do appear. See the discussion of the east face of the cross below.

Tradition suggests that a church or monastery was founded in the fifth century by Saint Patrick or one of his followers. Little beyond this tradition is known about the origins or history of the monastery at Carndonagh. Indeed, the supposition there was a monastery there seems to be based in large part on the presence of the Carndonagh Cross. The majority of the Irish High Crosses are related to a monastery. Their presence suggests the monastery in question had achieved a level of prosperity and importance.

Dating the Cross

There is some debate about the dating of the Carndonagh Cross. Estimates range from the 7th to the 10th century. As you will find below, some scholars claim a 7th or 8th century date for the cross. The best example is Francoise Henry. Her dating is reflected in a number of online sites including Megalithicireland.com; Megalithomania.com; tourdonegal.com; and discoveringireland.com. Others, including Peter Harbison and Robert Stevenson lean toward a 9th or 10th century date. Based on an early date, Henry saw the Carndonagh Cross as one of the earliest of the Irish High Crosses. This distinction is lost if the cross is dated to the 9th or 10th century. Some of the points in the discussion are mentioned below. You can, of course, draw your own conclusions.

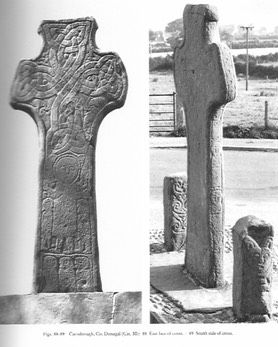

The dating of the Carndonagh Cross has frequently been related to the dating of the Fahan Mura Cross Slab. Harbison lists Fahan Mura among the High Crosses because “it has frequently featured in discussions about the chronology and development of the crosses.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 2) One of the similarities involves the interlace on the cross. Harbison describes the interlace on the east face as follows: “The head of the cross is occupied by an interlaced cross of two broad strands with pointed terminals.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 32) He describes the interlace on the east face of the Fahan Mura cross-slab as “interlacing which has a broad central band flanked on each side by a narrower band.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 88) See the comparative photos below, the Fahan Mura slab on the left and the Carndonagh cross on the right. (Harbison, 1992, Volume 2, Figures 88 and 277)

Francoise Henry, in works written between 1932 and 1967 proposed an early, 7th century date for the cross. Robert Stevenson, in a 1985 article, summarized her thinking as follows: “When Henry formed her views on the date of the Inishowen sculptures she thought that ‘The broad plaited ribbon existed for only a short time in Irish art’, the most notable examples being in the Book of Durrow. [Henry dated the Book of Durrow to the 7th century, but more recent scholarship has dated it to the 8th century. (Meehan, p. 22)] This, together with a kind of terminus post quem of 633 for the Greek Gloria formula inscribed on Fahan’s edge, and the series of primitive-looking slabs along Ireland’s west coast, seems to have been the basis for the 7th century dating. It was supported by her reference to very different Coptic slabs, which however had on them pediments and birds.” (Stevenson, 1985, p. 92)

Another aspect of the debate relates to an inscription on the Fahan Mura Cross Slab mentioned above by Stevenson. The inscription is in Greek and reads [in English], “Glory and honour to Father and to Son and to Holy Spirit.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 360). This is a doxology that was approved by the Council of Toledo in 633. This inscription was taken by Henry and others to confirm a 7th century date. However, the presence of this doxology on the cross-slab cannot limit the time frame of the cross-slab to the 7th century as it continued in use after that. “Kathleen Hughes pointed out that the only other Irish version of the doxology found in the Fahan inscription occurs in a late 8th century penitential.” (Harbison 1992, p. 375)

While Henry and others supported a 7th or 8th century date, Stevenson, Harbison and others support a much later 9th or 10th century date. Based on more recent archeological evidence Stevenson writes, “There seems altogether a stronger case to be made now than in 1956 for the Inishowen sculptures to be part of that widespread but locally differentiated interest in sculpture characteristic of Celto-Scandanavian Cumbria, Man, the Solway shores, Strathclyde and the Isles, spread out over the 10th and 11th centuries. Eclectic and often archaising so that sequential dating is difficult, latterly it was apparently prone to serious degeneration, so much so that some of its Galloway products have also been thought to be ‘primitive’.” (Stevenson, 1985, p. 94)

The Cross

Neither side of the Carndonagh Cross is divided into panels. On both the west and east faces there is roll moulding along the outer edge.

The West Face

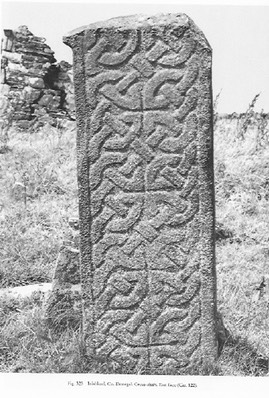

The entirety of the west face of the cross is covered with a ribboned interlace composed of a central ribbon with narrower ribbons on each side as seen in the photo to the left. (Harbison, 1992, vol. 2, fig. 87) This ribbon pattern is similar to that on the Fahan Mura Cross-slab discussed above in the section on “Dating the Cross.”

The North Side

The north side of the cross, which is not shown in the photos, is undecorated.

The East Face

On the lowest part of the shaft on the east face there are three figures, turned to the left. They wear long garments. Their position below the scene of the crucifixion led Peter Harbison to identify them as the “Three Holy Women Coming to the Tomb.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 32) This is a reasonable identification given the fact that in most all of the crucifixion scenes on the Irish High Crosses, Jesus appears to be triumphant rather than defeated. That is, as on the crosses, the scene of the crucifixion implies the victory of resurrection.

The Gospels vary in their description of who came to the tomb on Resurrection Sunday. In St. Matthew we read that it was Mary Magdalene and the other Mary, two women. (Mt. 28:1) In St. Mark it is Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James and Salome, three women. (Mk. 16:1) In St. Luke we read that it was an unspecified number of women who came to the tomb. Those mentioned by name are Mary Magdalene, Joanna, and Mary the mother of James, three named women. (Lk. 24:1-10) In St. John it is Mary Magdalene alone who comes to the tomb. She then runs to tell what she had seen and Simon Peter and "the other disciple, the one whom Jesus loved" came to see for themselves. (Jn. 20:1-4)

While the scene of the women coming to the tomb on Resurrection Sunday is crucial to the story of the resurrection, it is also true that the Gospels record that women who were followers of Jesus were watching the crucifixion itself from a distance. “Many women were also there, looking on from a distance; they had followed Jesus from Galilee and had provided for him. Among them were Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James and Joseph, and the mother of the sons of Zebedee,” three women. (Mt. 27:55-56). Thus another alternative would be to consider these women fit with the crucifixion scene rather than the resurrection scene. In either case the role of women as faithful disciples is lifted up.

The main section of the shaft offers us an image of the crucifixion. Jesus is clothed in a colobium-like garment that comes to below his knees. He has what appear to be short stubby arms. His arms may be bent at the elbow with only his forearms extended. His head is surrounded by a narrow roll moulding that Peter Harbison identifies as giving a hooded or haloed impression. (Harbison, 1992, p. 32)

There are two figures below Jesus’ outstretched arms and two figures above. The figures below Jesus’ arms have two possible interpretations. They could be taken to be Stephaton and Longinus depicted without their identifying symbols (a stick with a sponge for Stephaton and a spear for Longinus). These are the names given to the characters described in John 19:28-34. Longinus and his spear make their only appearance in the Gospels in this text. Stephaton appears in all four of the Gospels. (Mt. 27:45-48; Mk. 15:33-36; Lk. 23:36-37 and Jn. 19-28-34) Only in Luke is Stephaton identified as a solider.

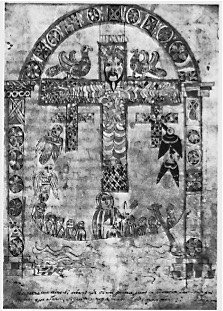

Harbison suggests that these figures may, instead, represent the two theives crucified with Jesus. Here also the Gospel stories vary to some degree about the details. See for example Mt. 27:38; Mk. 15:27-28; and Lk. 23:32-33. There is apparently a bird in a horizontal position above the head of the figure on Jesus’ right and an unidentified figure that could be a bird facing upward above the head of the figure on Jesus’ left. Harbison sees this as comparable to an image found in an 8th century manuscript of the Pauline Epistles that resides in a library it Wurzburg, German. (Harbison, 1992, v.1,p. 32, v. 3 fig. 885)

As seen to the left, this Wurzburg image depicts birds pecking at the thief on the right and angels accompanying the thief on the left. The Gospel of Luke tells us that one of the thieves derided Jesus while the other defended his innocence. The tradition is that the one descended to hell while the other was with Jesus in paradise. (Luke 23:39-43)

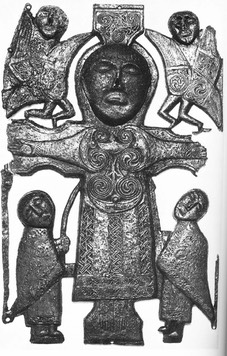

In the image to the left, the figures above Jesus’ arms are peacocks, a symbol of resurrection. On the Carndonagh Cross the figures above Jesus’ arms may be taken to represent angels. Harbison points to a comparison with the Crucifixion plaque from St. John’s near Athlone, now in the National Museum in Dublin. This image is seen to the right. (Harbison, 1992, v. 1, p. 32, v. 2, Fig. 901) Angels on each side of Jesus head are common on images of the crucifixion on the Irish High Crosses.

Carrowmore Crosses

In the townland of Carrowmore the site of the ancient monastery of Both Chonais is marked by the presence of two stone crosses. Tradition suggests that a monastery was founded here by St. Patrick, presumably in the late 5th or early 6th century.

In 2013, A Geophysical Survey was conducted at Carrowmore Ecclesiastical Complex, Inishowen. A brief report prepared by Max Adams and Colm O’Brien yielded the following findings.

"At Carrowmore magnetic anomalies, strongly indicative of a hitherto unknown double sub-circular ditch-and-bank enclosure, were recorded in a gradiometer survey. This appears to have formed the setting for the historically attested Early Christian monastery of Both Chonais and the burial ground whose physical presence is reflected in two high crosses, smaller marker stones, a rectilinear earthwork and ‘holy well’ site (Lacy 2010).” (https://historyofdonegal.wordpress.com/2014/10/04/carrowmore-survey-of-monastic-site-2013/)

North Cross

The cross is ringless and undecorated. It stands about 3.32m or 10 feet high. See the photo to the right.

The South Cross

The cross is ringless and stands about 2.85 m or about 9 feet high. There is one image on the west face of the cross that has been identified as the Majestas Domini. Jesus is flanked on each side by an angel. See the photo to the left

The Cross-base?

Near the two crosses is a stone with a socket that has been identified as a possible cross-base. See the photo to the left.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 3, C 2. The crosses are located south of the R244 about 5km or 3 miles east of Cardonagh.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Carrownaff aka Cooley

“Near the site of the church of Maghbile (Moville) in Bredach Glen, known as the church of Cooley, there is a fine specimen of an ancient monolithic cross.” (Doherty, p. 105)

This area is in the townland of Carrownaff, near Moville. The cross stands outside the gates of the Cooley cemetery.

Doherty described the cross as follows: “This High Cross of Cooley bears no inscription or decoration, and has four perforations within its circular body, and one perforation in the upper member. The cross faces east and west, has a height of 9 ft. 3 in. over the table slab in which it stands. . . .” He adds, “A foot-mark traditionally ascribed to St. Patrick, is pointed out on the slab in which the cross is fixed.” (Doherty, p. 106) This led Doherty to suggest the cross is as old as St. Patrick, which of course it is not. There is no explanation for the hole in the upper arm of the cross.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 3, C 3. The cross is located west of Moville as indicated on the map to the right that is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Clonca Crosses

The monastery at Clonca was an influential center for Christian evangelism in Inishowen from the 6th century. On the site are the remains of a 17th century church and two high crosses, one standing and relatively complete, the other the head of what was a very large cross. The standing cross is known as St. Baudan’s Cross. St. Baudan was the patron saint of the monastery.

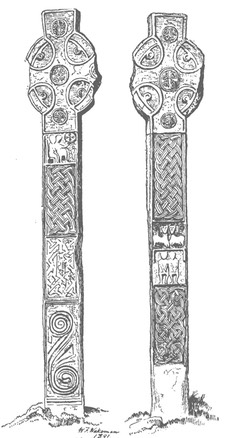

In an article on “The Cross of St. Buadon of Cluain-Catha (Clonca)” Doherty includes a sketch of the cross that assumes the head mentioned above belonged to the shaft that is standing. Apparently the head of the standing cross was missing at the time. The resulting image is shown to the left. (Doherty, p. 109) The cross of the illustration was never a composite cross. The illustration is useful, however, in seeing the designs on the shaft.

East or St. Baudan’s Cross

The cross is about 10 feet in height. The head was reconstructed in concrete about 1980. There is no decoration on the sides.

East Face:

E 1: Two animals with coiling tails

E 2: A fretwork pattern

E 3: A loose two-strand interlace

E 4: The Multiplication of the Loaves and Fishes (?) A seated figure holds up a disc representing a basket or tray with five circular loaves. Below are two fish. (Harbison, 1992, p. 44)

Arm: An Orans figure. The orans was a posture of prayer. This image is not pictured.

West Face:

Bottom: undecorated

W 1: Two strand interlace.

W 2: Saints Paul and Anthony in the Desert. This image has two figures sitting frontally side by side. Above them are two lion-like creatures, each with a crozier appearing above their back. “The two figures are presumably Saints Paul and Anthony, to whom the croziers belonged, and the lions are those who came to assist St. Anthony in digging a grave for St. Paul.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 4)

W 3: Two-strand interlace.

West Cross

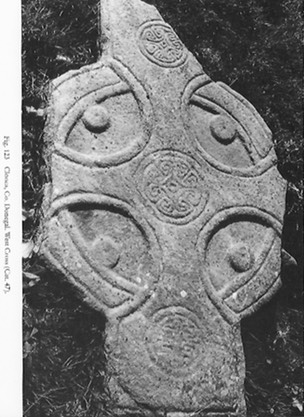

All that has survived of this cross is the head, probably the base and an arm fragment that is in the church. The head and arm fragment are pictured to the left. (Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Figs. 123, 124)

“The head is imperforate, and the cylinders are attached to the inner surface of the ring. Around the edges of both shaft and ring there is a roll moulding. At the centre of the head there is a roundel with five interconnected C-shapes with their backs to a central boss with central depression. A similar roundel is found on the shaft, while that on the top may have had a fretwork pattern.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 44)

I have turned the photo above right so that the photo depicts the upper shaft of the cross. Looked at in this way it is easy to believe the arm in the church was, in fact one arm of the cross head. The roundel is of similar design. My own photo of the arm fragment is to the left below. I was unable to locate the cross-head.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 3, C 2. Located east of Carndonagh north of the R244. The turn is about 5km or 3 miles east of Carndonagh and very near the turning to the south for the Carrowmore crosses. The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Clontallagh (Cluain tSalach) aka Mevagh

Little is known about this cross or the church where it now stands. Harbison gives it one sentence, “An undecorated cross, about 2.60m high and without ring stands in an old churchyard about 2 miles north of Carrigart.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 58)

A more complete description can be found on he Historic Environment Viewer. “A cross (DGF016-004002) carved from a single slab 2.5m in height and c. 15cms thick. the angels where shaft and arms meet have been hollowed and emphasized by a small knob-like projection. It stands to the S of the church.”

Tradition suggests that Colm Cille founded the Church at Mevagh in Clontallagh townland. He is also credited with erecting the High Cross there. It is said that he left the track of his fingers in the stone. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosguill) As the earliest of the High Crosses post date Colm Cille, the cross was not erected by Colum Cille. The cross may have been dedicated to him when it was erected and the tradition morphed over time. The "Map of Monastic Ireland" marks a possible monastic site in the area of Mevagh but does not name it.

The two faces of the cross are pictured above.

The small cross pictured to the left is on the main road just where the lane that leads to the church site is located. It is said this is where St. Colum Cille’s donkey sat down. Presumably either when Columba founded the monastery or when he, according to tradition, delivered the cross.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 2, G 2. Located north of Carriage Airt. On the map to the right the site is indicated by the largest of the circles. The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Fahan Mura Cross

The Monastery and Saint

When the monastery at Fahan was established and by whom are both uncertain. Henry reported that Colgan, a 17th century Franciscan historian credited the foundation of Fahan to St. Columba. She goes on to suggest this may be more reflective of a connection between Fahan and other Columbian monasteries rather then an historical fact. She also tells us St. Mura is the patron saint of the monastery. (Henry pp. 127-128) St. Columba is, of course, one of the patron saints of Ireland, along with St. Patrick and St. Brigit. St. Columba lived from 521 till 597. St. Mura lived from 550 till 645, nearly 100 years. He was a direct descendant of the founder of the Northern O’Neill, the most powerful clan in the north of Ireland for several hundred years. When what we know is sorted through, the evidence suggests that St. Mura was the founder, or a very early Abbot of the monastery and that its foundation can be dated to the late 6th century.

Like most Irish monasteries, Fahan was sacked by the Vikings in the 10th century and again in the 13th century, when it was abandoned. A later monastery was destroyed in the 16th century.

The Cross

The dating of the Fahan Mura cross is open to debate. Harbison discusses this in some detail. The Fahan Mura cross slab and the cross at Carndonagh are closely linked by their artistry. They have traditionally been compared to the Book of Durrow and dated to the 7th century. This has led to the conclusion that in these two monuments we are seeing the "beginnings of the development of the Irish High Cross.” The Greek inscription, which will be discussed below, led Berchin to date the cross in the 8th century and Hughes found the only other version of the Greek inscription in the late 8th century. A 9th century date has also been proposed. Harbison seems to support an early 9th century date as probable while Stevenson offered a 10th century date and connected the cross and slab design to a Scottish development. (Harbison 1992, pp. 375-6) For additional detail see the discussion of the Carndonagh cross above.

The illustration to the left is found in Doherty, p. 113.

Harbison and others include the Fahan Mura cross slab with the Irish High Crosses because of the role it has played in discussions regarding the origins and evolution of the High Crosses. (Harbison, 1992, p. 88)

East Face

In both the illustration above and the images to left and right below, the east face is on the right. Doherty describes the design as follows: “The head of the cross on this side is surmounted by a triangular pediment that presents the appearance of the wings of a dove; within the triune interlacings are a central boss, with four others in the exterior concaves that form the arms of the cross.” (Doherty, pp. 112-113) Harbison interprets the image atop the cross as representing “two birds facing one another in the gable at the top of the slab, their curving beaks crossing one another. (Harbison, 1992, p. 88)

West Face

West Face

This face of the cross also contains a cross. This cross has a more elaborate interlace than that on the east face. A rounded boss is at the center of the cross. On either side of the shaft of this cross there is a figure. Each has long strands and a steep-fronted head. These have been interpreted both as ecclesiastics and as women. (Harbison, 1992, p. 88)

Macalister discovered what he considered to be additional inscriptions both above the two figures, and on their robes. While guessing at what the inscription might say he considered that the two above the heads of the figures were part of the formula “a blessing upon . . . “ Macalister was unable to make sense of the inscriptions on the robes of the figures, and others have identified them as simply decoration on the robes. (Macalister, p. 90-91)

South Side

The south side of the cross is undecorated.

North Side

On the north side is a two-line inscription. Doherty, writing in the 1890’s found it impossible to decipher. He assumed that the wording was in Irish and that it suggested the slab was erected to commemorate a distinguished individual. (Doherty, p. 112) Writing in 1929, Macalister was the first to identify the text as Greek, not Irish. With this insight, he was able to decipher the text as the Gloria Patri, “Glory and Honor to Father and to Son and to Holy Spirit.” He identified the Greek as that of “an ecclesiastical Latinist,” and noted that the spelling contained some mistakes. He considered it to be part of the original cross, not a later addition. (Macalister pp. 93, 96)

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 3, A 4. The Cross Slab is marked on the map. The graveyard and old church are located just south of Fahan on the R238. The white circle on the map is not the cross-slab. It is one of the red dots between the road and the old church. The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Inishkeel or Ionascail Cross

Inishkeel is a tidal island in the Gweebarra Bay near the town of Naran on which St. Connell aka Connall Caol founded a monastery sometime in the sixth century. On the island are the remains of two churches: St. Connall's and St. Mary’s. St. Mary’s has a thirteenth century chancel and a late medieval nave. St. Connall’s seems to have been constructed in the fourteenth century. There are several cross slabs on the island and a stone known as St. Joseph’s Bed. There are also two holy wells, dedicated respectively to St. Connall and St. Mary. (Meehan, pp. 116-117)

McGill tells us of a passage in the Annals of the Four Masters for 619 that suggests Inishkeel may have been a noted monastery in the early 7th century. He supposes that the early buildings consisted of beehive huts or clochans and small stone oratories. (McGill, p. 56)

The photo to the left is from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 323.

McGill examines in detail the possible identity of St. Connal Caol, the supposed founder of the monastery on Inishkeel. He writes: “It is my opinion, . . . that Christianity was introduced to Inis Caoil by missionaries, travelling by boat, who were inspired by Coelan of Nendrum. Possibly the latter originally hailed from the Caol or Achad Cail areas of south Co. Down. We have noted already that Coelan was venerated on a little island in north Donegal and that Tassach, also associated with east Co. Down, was celebrated on the island of Rathlin O’Birne off the coast of south-west Donegal. Whether the cult of Coelan arrived in Inis Caoil in the form of Coelan or Coel/Cael or Conall Caol is a question, but I would estimate that it arrived as Coelan and that, since the largest early population group which the missionaries had to convert were the Cenel Conaill, the cult gradually took on the name of Conall. It may have taken a few generations to do so, but it seems too much of a coincidence to find such an eminent saint as Conall among the Cenel Conaill, and the attraction of a combined ancestral (Conall Gulban) and Christian (Conall Caol) cult must have appealed.” These suppositions are based on the idea that saint’s pedigrees are fabricated to reflect the family that provided the successors to the abbacy of the monastery. (McGill, p. 111)

McGill concludes, “There is no doubt that in the early stages of Christianity in the north-west the ecclesiastical foundation on Inishkeel was an important pivot, its influence reaching into much of south-west Donegal. It is likely that the founder was an inspirational figure whose charisma fueled the faith of later generations of ecclesiastics on the island. That belief in him in the form of Conall of Inishkeel has been harboured by people down through the ages and, carefully and lovingly handed down to us, is far more important and relevant than a mere biography of the man.” (McGill, p. 112)

McGill concludes, “There is no doubt that in the early stages of Christianity in the north-west the ecclesiastical foundation on Inishkeel was an important pivot, its influence reaching into much of south-west Donegal. It is likely that the founder was an inspirational figure whose charisma fueled the faith of later generations of ecclesiastics on the island. That belief in him in the form of Conall of Inishkeel has been harboured by people down through the ages and, carefully and lovingly handed down to us, is far more important and relevant than a mere biography of the man.” (McGill, p. 112)

Saint Connell's legend has an interesting story about how he came to Inishkeel. He was hot tempered and one day, while working with his father, he flew into a rage and killed him. As punishment, he was exiled to Inishkeel. He was sentenced to remain there until he became calm enough that a bird could build a nest in his hand. Seven years later he fell asleep one day and woke to find that a bird had indeed built a nest in his hand. A similar “nest in the hand” story is told of St. Kevin of Glendalough and seems to symbolize not only a peaceful or contemplative nature but also a deep connection with nature. (Meehan, p. 116)

Harbison has little to say about the cross, which is a partial shaft. Only the east side is decorated. This side bears an extensive panel of broad interlace. There is raised moulding at the edges. The only clear indication this was a cross is the presence on the upper south corner of the shaft of what must have been the beginning of a section of the ring. (Harbison, 1992, p. 99)

There is a more highly decorated cross slab on the island that is about four feet tall with a rounded top. On each face is a Latin cross made of interlacing. On one side are two hooded figures in profile, standing under the arms of the cross, while beneath the cross two figures stand facing one another bowing to what may be an altar between them. (Meehan, pp. 117-118) This cross slab is known as the “swan cross.” Photos of this cross slab can be seen at megalithicireland.com and earlychristianireland.org.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 8 E 1/2. Located across from Naran off the R261. This is a tidal island and according to a local the tide is low enough to walk there only once or twice a year, usually near the vernal and autumnal equinoxes. I was not able to visit the site, but it may be possible to hire a boat to take you across. The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Kilcashel Cross

This cross is known as St. Conball’s Cross. It is located 100m west of the old graveyard at Cashel in the Loughros Peninsula. It stands 1.6m high and measures 65cm across the arms. It is 11cm thick. The only decoration is a ringed cross on the south face.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 7 ???

Ray (Raith) Cross

The “Map of Monastic Ireland” does not show any monastery or possible monastery on the site. Legend connects the cross with St. Colm Cille, who founded numerous churches and monasteries in this part of Ireland in the sixth century. The cross is know by some as St. Colm Cille’s Cross. The stone for the cross has been associated with the Muckish Mountain near Ray. It is said that Colm Cille intended the cross for the monastery at Tory Island.

The story of how the cross ended up at Ray is a later invention because, as with the Clontallagh cross above, the cross post dates the time of Colm Cille. The story is that Colm Cille traveled to Tory Island, the intended site for the cross, with two companions. They were Fionan and Begley. When they arrived on Tory, Colm Cille found he had left his prayer book on the mainland. He promised he would give whatever was desired to the companion who retrieved the book. Fionan went and found the prayer book sheltered under the wings of an eagle. As his reward he asked that the cross be given to Ray. (http://www.colmcille.org/torry/2-09)

The Historic Environment Viewer states that “There are unconfirmed and unlikely claims that the cross was brought from Tory Island in the last century. John O’Donovan (O’Flanagan 1927, 39) saw it in its present state in Ray Graveyard in September 1835 and was told it had been knocked by a storm about a century before.”

The Ray Cross is located inside the ruins of the Ray Church, where it was moved for protection. The cross is 5.56m high and 2.26m across the arms. The shaft and ring are thin, at 15cm. The cross was apparently standing until 1750 when it was knocked over in a storm. It then lay broken in the graveyard until the 1970’s when the Office of Public Works set it up in the church and added support. (http://www.arasainbhalor.com/HistoryofFalcarragh.htm)

There are raised flat panels on the head of the south face of the cross —square in the center and slightly rectangular on the arms. These are visible in the photo above left. There is no other decoration. (Harbison, 1992, p. 162)

Because it has no decoration, the cross cannot be dated based on artistic styles. In shape, it resembles the late 8th century St. John’s Cross on Iona. A connection is certainly possible as several of the abbots of Iona in the 7th century came from this area of Donegal. (http://www.colmcille.org/torry/2-09 )

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 2, E 3. The site is located north of the N56 about where there is a camera on the Road Atlas map. The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Tory Island Crosses

Tory Island lies in the North Atlantic about nine miles off the northwest coast of County Donegal. It is about three miles long and one mile wide. Forde notes that Tory is one of the early places mentioned in the Bardic History of Ireland. Legend has it that Tory was a stronghold of the Fomorians, mythic demigod inhabitants of Ireland. Later, in historical times the Scandinavians, who raided and pillaged the coasts of the Pretanic (British) Isles, had a settlement there. (Forde) The name Tory (Toria) means outlaw, reflecting the fact that raids were often carried out from Tory. During Celtic times, before the conversion of the island, it was a Druidical center. (Meehan, p. 120)

The Monastery and Saint

A monastery was founded on Tory Island some time prior to 560. St. Columba (Colm Cille) is credited with its establishment. Colm Cille, along with St. Patrick and St. Brigid is one of the patron saints of Ireland. He established many churches and monasteries both in Ireland and later in Scotland.

Forde tells an interesting story of the founding of the Tory monastery that bears quoting at length. “The legend says; Columba, being admonished by an angel to cross into Tory, set sail with several other holy men for the Island, that there arouse a dissension among them with respect to the individual who should consecrate the Island, and thereby acquire a right to it in the future, each renouncing from humility and a love of poverty the office of consecration and right of territory. They all agreed with St. Columba that the best way to settle it was by lot, and they determined by his direction to throw their staves in the direction of the island, with the understanding that he whose staff reached nearest to it should perform the office of consecration and acquire authority over Tory. Each threw his staff, but that of Colum-kille at the moment of issuing from his hand assumed the form of a dart, and was borne to the Island by supernatural agency.

“The saint immediately called before him Alidus, son of the chief of the Island, who refused to permit its consecration or the erection of any building. St. Columba then requested him to grant as much land as his outspread coat would cover. Alidus readily consented, conceiving the loss very trivial, but he had soon reason to change his mind, for the saint’s cloak, when spread on the ground, dilated and stretched so much by its divine energy as to include within its border the entire island. Alidus was roused to frenzy by this circumstance, and incited or hunted upon the holy man a savage, ferocious dog, unchained for the purpose, which the saint immediately destroyed by making the sign of the Cross. The religious feelings of Alidus were awakened by this miracle, says the legend, He threw himself at the saint’s feet, asking pardon, and resigned to him the entire Island.” (Forde)

The Annals of the Four Masters reports that the monastery was destroyed in 612 and that the Church was rebuilt four years later. It is also said that St. Eman was abbot there about 650. (Crumlish, pp. 23-24) The monastery continued in existence until 1595 when it was sacked by the Governor of Connacht. (Meehan, p. 122) Still visible are the shaft of a round tower, three altars and a graveyard, the site of a church, and of special importance here, a Tau Cross and two additional cross fragments.

The Crosses

Harbison lists three cross related items on Tory Island. The first and most obvious is a Tau or T-shaped Cross near the top of the pier at West Town. The second is actually two fragments that Harbison believes were part of the same cross. The third is a tentative identification of a limestone slab as part of a cross shaft. (Harbison, 1992, pp. 173-4)

The Tau Cross: Such a cross is rare in Ireland. There is another at Killinaboy in County Clare, and a possible third at Killegar in County Wicklow. The Tau cross is also known as a St. Anthony’s or Egyptian cross as it reflects the shape of the Coptic crozier. Its depiction in Christian art is known from the third century.

While only two or three Tau crosses exist in Ireland, it also appears in the form of a crozier in other stone carving including the Market Cross at Kells in County Meath and the Doorty Cross at Kilfenora in county Clare. The above mentioned representations are typically dated to the twelfth century. It would be reasonable to date the Tau Cross on Tory to the same period. (Crumlish, p. 24)

The cross stands 1.88m tall and is 1.15m across the arms. The arms taper a bit toward the ends and it is clear that it never had an upper limb. "The south side of the shaft is rounded, but the north side and the two faces are flat.” It appears there was never any decoration. (Harbison, 1992, p. 173) See the photos left and right above.

The Tower Cross:

This cross is so named because the two fragments that compose its remains are among other stone fragments close to the Round Tower The first fragment, seen below to the left and right, bears a figure, probably Christ, standing with forearms stretched out and hair falling down on both sides of his face.

The second piece, below to the left and right, is fitted into a circular base and has apparently been placed upside down. A partial figure is visible with the feet at the top. (Harbison, 1992, p. 173)

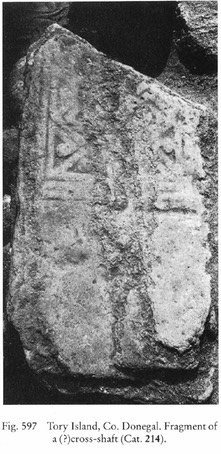

Cross Fragment:

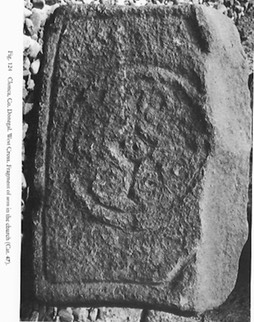

This limestone slab is decorated with fretwork and may have formed part of a cross similar to the Ray Cross. It was also located near the Round Tower before 1992. As noted above, there is a tradition that the Ray cross was intended for Tory Island, though it was almost certainly never there. The photo to the right is from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 597.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 1, D 2. Ferry service is available from Min Larach on the R257 on the north coast of Donegal and from An Bun Beag off the R257 on the west coast. The Tau Cross is at the top of the pier and the fragments are to the west near the base of the Round Tower, marked by the white circle on the map. The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Resources Cited

Adams, Max and O’Brien, Colm, A Geophysical Survey at Carrowmore Ecclesiastical Complex, Inishowen, https://historyofdonegal.wordpress.com/2014/10/04/carrowmore-survey-of-monastic-site-2013/.

Charles-Edwards, T.M., Early Christian Ireland, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Crumlish, Richard, “The Archaeology of Tory Island”, Archaeology Ireland, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Spring, 193), pp. 22-25.

Doherty, William J., “Antiquities of Inishowen, County Donegal”, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy (1889-1901) Vol. 2 (1891-1893), pp. 100-116.

Forde, Hugh, “Sketches of Olden Days in Northern Ireland”, http://www.booksulster.com/library/sketches/toryisland.php

Harbison, Peter; The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey, Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volumes 1 and 2

Henry, Francoise, Irish Art in the Early Christian Period to A.D. 800, Methuen & Co. LTD, London, 1965.

Lacy, Brian, Cenel Conaill and the Donegal Kingdoms AD 500-800, Four Courts Press, 2006.

Macalister, R. A. S., “The Inscriptions on the Slab at Fahan Mura, Co. Donegal”, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Sixth Series, Vol. 19, No. 2 (Dec. 31, 1929), pp. 89-98.

McGill, Lochlann, In Conall’s Footsteps, Brandon Book Publishers, Dingle, Co. Kerry, 1992.

Meehan, Bernard, The Book of Durrow: A Medieval Masterpiece at Trinity College Dublin, Town House and Country House, Trinity House, Dublin, 1996.

Meehan, Cary, Sacred Ireland, Gothic Images, 2004

Stevenson, Robert B. K., “Notes on the Sculptures at Fahan Mura and Carndonagh, County Donegal,” The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 115, (1985), pp. 92-95.

The Map of Monastic Ireland, Ordnance Survey Office

Websites

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosguill