This page highlights Three High Crosses found in County Monaghan. They are: Clones, Old Donagh and Selloo. The location of County Monaghan is indicated by the red star on the map to the right.

History of County Monaghan

The modern County Monaghan came into existence in 1585 following a conference of Sir John Perrot and a number of Irish chieftains. The leading family was McKenna.

Neolithic Monaghan: (c4000-2400 BCE)

The area of present day County Monaghan was settled by Neolithic farmers as illustrated by excavation at Monanny, near Carrickmacross, where three rectangular houses were identified. (Walsh p. 9) Settlement sites were typically located near streams that provided a supply of salmon.

Bronze Age Monaghan: (2400-500 BCE)

The population of County Monaghan in the Bronze Age (c. 2400-500 BCE) was likely sparse. This is suggested by the scarcity of burnt mounds (fulachta fiadh) in Monaghan. (Life and Death in Monaghan p. 9) Burnt mounds are characterized by large quantities of head shattered stone. It is thought these were cooking places that were used over a broad period of time. (Irish Archaeology)

Iron Age Monaghan: (c 500 BCE - 400 CE)

During the Iron Age there is, to date, no archaeological evidence for habitation in what is now County Monaghan. This, of course, does not mean there were no people living there.

Early Medieval Monaghan: (c 400 - Late 12th Century CE)

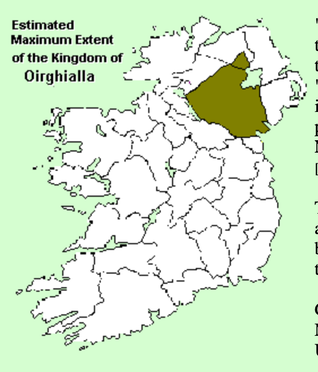

During the Early Medieval period (c 400 CE - late 12th Century CE) there was a significant population in the area. County Monaghan has “669 known ring forts and 74 crannogs. . . . Early Medieval sites make up 87% of all known archaeological sites in County Monaghan. The people who lived in Monaghan at this time are known as the Airghialla (anglicised to Oriel).” (Life and Death in Monaghan, p. 12)

Airgialla (Oriel)

“The ancient kingdom of Airgialla was formed around AD 330. At one time, it included the southern parts of the modern counties of Tyrone and Derry, as well as much of Armagh, Monaghan and Fermanagh. With its royal site at Clogher, it included the Ui Thuitre, Ui Cremthainn, Ui Meith, Airthir, Mugdorna, Dairtre and Fir Rois tribes. Later the septs of the MacMahony, O'Hanlon, and O'Neill of the Fews were prominent in this area.” (Rootsweb)

The Anglo-Norman advance in the 13th century broke up Oriel, but Monaghan remained dominated by the MacMahons and lay outside the main area of Anglo-Norman influence.” (Rootsweb)

The map to the right was found at http://sites.rootsweb.com/~irlkik/ihm/colla.htm.

“A steady push by the Cenel nEogain in the 7th and 8th centuries reduced the size of the Aighiallan federation as the people of northern Airghialla came to be treated as sub-kingdoms of the Cenél nEógain. During a similar period the southern branches of the Airghialla came under the dominion of the southern Uí Néill kingdoms of Mide and Brega. By the 9th century Airgialla proper, as a political entity, was practically confined to the modern counties Armagh, Monaghan, Fermanagh, and part of Louth, with the Uí Thuirtri kingdom in east Tyrone in process of being absorbed into the Cenél nEógain over-kingdom of Ailech.” (Rootsweb)

Ecclesiastic History

During this Early Medieval/Early Christian period there were at least 15 confirmed or supposed monastic sites in present day County Monaghan. Two of these, plus Seeloo that is not listed below, had high crosses . According to the List of Monastic Houses in County Monaghan, the following early monasteries were located in the area that is now County Monaghan.

Carrickmacross Monastery: early site, founded before 845

Clones Abbey: early site, Gaelic monks founded c 549/50 by St. Tigernach

Clontibret Monastery: early site, Gaelic nuns, patronized by St. Colman

Connabury Monastery: early site, Gaelic nuns, founded before 740

Donagh Monastery: early site, Gaelic monks

Donaghmoyne Monastery: early site, founded by St. Patrick

Drumsnat Monastery: early site, patronized by St. Molua

Errigal Trough Monastery: early site, Gaelic monks

Inniskeen Monastery: early site, founded before 587

Kilmore Monastery: early site

Monaghan Monastery: early site

Muckno Monastery: early site, Gaelic monks

Tehellan Monastery: early site, Gaelic monks, founded 5th century by St. Patrick

Tedavnet Monastery: early site, Gaelic nuns

Tullycorbet Monastery: early site

With the reorganization of the Irish church at the Synod of Rath Breasail in 1111, the area that was Airgialla was in the Archbishopric of Armagh and divided, for the most part between the diocese of Armagh and Clogher.

Clones Cross (Crossmoyle)

The Monastery and the Saint

The monastery at Clones was probably established in the sixth century. The traditional founder of the monastery, Tigernach of Clones died in 549. As evidence of this early date, Tirechan, a seventh century biographer of Saint Patrick "implies that Clones was a well established church in his day.” (McCone, p. 307) During the seventh century, Clones was closely associated with the nearby monastery at Ardstraw. Together, these two monasteries seem to have been rivals, for episcopal influence, with the Columba monasteries of the Cenel Conaill to their north and with Armagh to their east. The Columba monasteries looked to the spiritual leadership of Saint Columba or Colum Cille and the monasteries associated with Armagh looked to the spiritual leadership of Saint Patrick.

The photo to the right is an artistic depiction of Saint Tigernach of Clones. http://sanctiobliti.blogspot.com/2013/09/st-tigernach-patron-saint-of-clones.html

The Hagiography of Saint Tigernach tells us that his father was a Leinsterman and his mother of the Airgialla in Ulster. His story states that, like Patrick, he was captured by pirates. However, Tigernach was taken from Ireland to Britain. Later, he was educated with Saint Ninian at Candida Casa, located in what is now southwest Scotland. Like Patrick, he visited Rome before returning to Ireland. His hagiography seeks intentionally to put Tigernach on a par with Patrick. This reflects the competition for primacy among the groups of monasteries referred to above.

This competition was largely due to the struggles of the secular leaders of the various kingdoms of ancient Ireland for political supremacy. Each ruler sought enhanced authority for the chief monastery or monastic parochia of their area. And so the monastic parochia became part of the political calculation. In Ireland a parochia could be composed of several monasteries in a geographic area. But it could also stretch beyond a given geographic district. For example, Tigernach of Clones first founded a monastery in Leinster, the land of his father. When he moved north and established three monasteries in Ulster, the Leinster monastery continued to be part of his parochia. (McCone, p. 320)

Several additional examples of how the competition between saints and their parochia were manifested both underlines the competition and shapes out a bit more of the history of Clones. It was in the eighth century that the Lives of Tigernach of Clones and Eogan of Ardstraw were likely written. Those seeking to elevate Eogan, also from Leinster, claimed he came north first to found Ardstraw then helped Tigernach found the three monasteries attributed to him, including the one at Clones. The Life of Tigernach, on the other hand, lacks any mention at all of Eogan. (McCone, p. 319)

Pictured to the left is the Round Tower at Clones. Pictured to the right is a sarcophagus that is said to house the remains of Saint Tigernach.

Tigernach’s life also angles for influence over Armagh. There is a story there that Duach, an Abbot of Armagh who died in about 548. made a pilgrimage to Clones to visit Tigernach. Point one for Clones. On his way home to Armagh, Duach died. In a vision, God informed Tigernach of Duach’s death. In response, Tigernach hurried to the spot and raised Duach from the dead. Point two for Clones. To top things off, Duach is reported to have said, “Tigernach on earth, Tigernach in heaven.” Game, set and match to Clones.

Illustrating the complexity of the struggle for monastic influence on the one hand and for autonomy on the other, The Life of Tigernach also links him with Saint Brigit of Kildare. The Life tells us that it was Brigit who baptized Tigernach and named him. It was also Brigit who, after Tigernach returned to Ireland who sponsored his elevation to bishop. She is described as his spiritual mother. Of course, at this time, Kildare was another rival for the position of chief parochia of Ireland. (McCone, p. 322)

McCone describes what is called the “Sletty Syndrome.” “If a powerful church nearby is threatening your independence, protect yourself by submission to a powerful church further away whose control is likely to be less pervasive and irksome.” (McCone, p. 323) This is exactly what Clones did in aligning itself with Kildare. As time went by and the balance of power shifted, Clones became a pawn in a struggle between Armagh, Kildare and Clonmacnoise. (McCone, p. 325)

Like most monasteries, Clones was attacked and destroyed several times, in 836, 1095, 1184 and again in 1207. In the seventeenth century Clones was again destroyed following the suppression of the monasteries by Henry VIII. Sometime in the thirteenth century the monastery at Clones became an Augustinian Abbey.

On the south side of Clones, along Abbey Street are the remains of a twelfth century church, a 22m high round tower and a ninth century sarcophagus that is said to house the remains of Saint Tigernach.

The Cross

The High Cross at Clones, located in the Diamond in town center, is a composite formed of fragments of two crosses. The largest fragment is the shaft of a cross that appears to be complete. The second fragment is the head of a different cross that has been set on the shaft. These fragments stand on a base that is undecorated. On the top of the head is another fragment that dates to the eighteenth century and does not belong to either cross. (Harbison, 1992, p. 45)

The original locations of the crosses are unknown, though it would be reasonable to connect them with the Clones Monastery. They are both sandstone and may date to the tenth century. In the present location the cross sits at an angle. This offers some confusion as the side Harbison refers to as the South-East Face, Meehan simply refers to as the South Face. We’ll begin the description of the carvings on the cross there.

The following descriptions of the carvings on the cross follow Harbison.

The South Face:

Panel S 1 depicts Adam and Eve Knowing their Nakedness. In typical fashion, the two stand under an arched fruit laden tree. They are shown frontally and are covering their nakedness. The serpent can be seen coiling up the tree and facing the left figure, who is Eve. See the photo to the right.

Panel S 2 illustrates the Sacrifice of Isaac. Abraham is on the left holding a sword diagonally in his right hand. With his left he seems to hold Isaac, who is bending over the altar holding a bundle of faggots. Above Isaac is a ram with the image of an angel visible behind it. See the photo to the left.

Panel S 3 shows Daniel in the Lions’ Den. Daniel stand frontally with forearms stretched out. Above and below each arm is a lion. See the panel below right.

Panel S 4 was decorated with small bosses and is much worn.

The Head: See the photo below left.

The lower arm of the head of the cross contains a horseman and perhaps a riderless horse, above which is a motif of linked bosses.

The center of the head is another depiction of Daniel and the Lion’s Den showing as above Daniel and four lions. Remember the head is from a different cross than the shaft.

The west arm contains an image identified by Harbison as Cain Slays Abel. There are three figures. In the center Cain raises a club to strike Abel on the right. On the left, with a hand on Cain’s shoulder is God.

The east arm may be interpreted as Joseph Interprets the Butler’s Dream. Two figures hold an upright staff resembling panel E 1 of the Cross of the Scriptures at Clonmacnois.

Above the center are the legs of two frontal figures that cannot be identified. At the very top, as noted above is an eighteenth century addition. (Harbison, 1992, p. 45-46)

The West Side: contains a panel of interlace above which is a panel with small bosses, above which is another panel of interlace. The box at the top of the shaft is decorated with bosses. See the photo to the left.

There is interlace and fretwork on the bottom of the ring and arm respectively. A winged angel adorns the end of the arm. (Harbison, 1992, p. 46)

The North Face

Panel N 1 contains an image of the Adoration of the Magi. Mary is seated and holding the child. A boss above her head represents the star. The other three figures represent the magi bringing gifts. See the photo to the right.

Panel N 2 represents the Marriage Feast of Cana. The three figures in the top row seem to represent Mary, Jesus and the steward of the feast. On the bottom row are four figures. The one on the left seems to hold out a container toward the figure beside him. That figure may be pouring water into a jar in front of him and above a row of four other jars that line the bottom of the panel. See the photo to the left.

Panel N 3 shows the Multiplication of the Loaves and Fishes. In the center of the image is a basket holding fish. Above the basket is the figure of Jesus. The figures on his left and right hold the basket. Below and across the bottom of the panel twelve small baskets can be discerned. In the story, they held the bread that was left over after the miracle. See the photo to the right.

Panel N 4 is part of the box at the top of the shaft. It appears to have been decorated with very worn bosses. See also the photo to the right.

The Head: The images on the head of the cross are worn and not easily discerned in the photo to the left. On the shaft is one figure turned left. In the center of the head is an image of the Crucifixion. Jesus is depicted with Stephaton (bringing vinegar) and Longinus (with a lance). There is an angel above each of Jesus’ arms.

Each arm of the cross bears an image of one of the two thieves crucified with Jesus. Each is flanked by soldiers who seem to be beating them.

The East Side is dominated by one long panel of interlace. The box at the top has a central boss with five smaller bosses around it. The underside of the ring and arm mirror the West Side. (Harbison, 1992, pp. 46-47)

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 18, E4. The cross is located in the Diamond in the center of Clones in front of Saint Tigernach’s Church of Ireland. The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Old Donagh

The Site

Little is known of the origins of the church at Donagh, or of the cross that now stands there. Maloney notes that Saint Patrick is said to have passed that way in the fifth century. By tradition, he blessed a holy well nearby. In 1492 the site was referred to (in Latin) as Dompnach inter gums or ‘the church between the bogs.’ Maloney suggests the name might refer instead to a Muadan or Mellan, a disciple of Saint Patrick and the patron of the nearby parish of Errigal Truagh. (Maloney)

Whether there was ever a monastery there, or how early the church was established is not know. Dates ranging from the ninth to the fourteenth century have been suggested for the High Cross. Because Harbison includes the cross as one likely carved before 1200, we are on firm footing to suggest a date between the ninth and twelfth centuries.

In the fifteenth century the church was active and many of the priests were members of the Treanor family. Following the Reformation the church and church lands came into the possession of the Church of England. In the photo to the right the remains of the old church can be seen.

In the fifteenth century the church was active and many of the priests were members of the Treanor family. Following the Reformation the church and church lands came into the possession of the Church of England. In the photo to the right the remains of the old church can be seen.

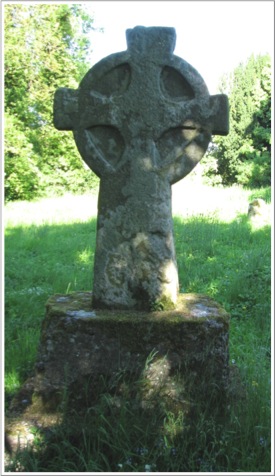

The Cross

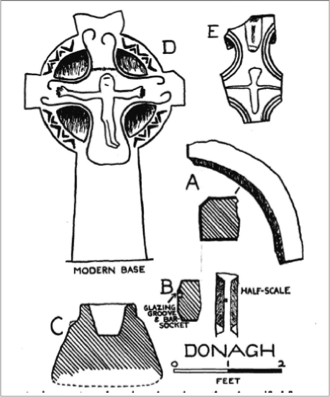

The Old Donagh cross was found in 1911 as will later be described. In 1939 a section of another cross was found nearby (E) in the illustration below. It is in the possession of the Monaghan County Museum (item 2002:4). There is also a cross base on the site known as the “Warty Well” as it is said to offer a cure for warts.

As noted above, the cross itself was found in 1911. Francis Joseph Bigger and Shane Leslie visited the graveyard and reported: “we looked around to find any trace of the cross, thinking it might have been destroyed or removed by the older race to preserve it from desecration, as Monaghan had much turbulence in the Plantation and even later times. After diligent search I came on a mossy stone level with the ground. On removing some grass and earth, I found it unshakable, thus proving it had some depth in the ground. Further excavation revealed the head of the lost cross of Donagh.” He goes on to describe how Leslie had it set up again and then notes the carvings visible on it. “It has upon its east face the figure of our Lord carved in the old Irish way.” (Bigger, p. 6)

According to local tradition, the cross was the inauguration site of the McKenna chieftains of Truagh. As a result it has also been called the McKenna Cross. (Moloney)

The photos to the left and right illustrate the two faces of the cross. While the original orientation of the cross cannot be know for certain, the crucifixion scene typically appears on the west face of the cross. See the photo to the left.

The image to the right does not have any apparent figural or ornamental carving.

The illustration to the left comes from the Moloney article online. Item “A” is identified as part of a door-jamb. Item “B” is identified as a three foot uncured window-mullion. The “Wart Well” or cross base is item “C”. The Donagh Cross is “D” and a fragment of another cross mentioned above is item “E”.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 18, G2. The Old Donagh graveyard is located just southwest of Glaslough. On the west side of Glaslough the R185 takes a sharp turn to the east. Going west from there is the Glaslough Road. Take the Glaslough Road. Just after turning west on the Glaslough Road you turn to the southwest on an unnamed road. The graveyard is located in the rough triangle seen in the lower left corner of the map to the right, near the narrow end of the triangle. Take the northern side of the triangle and a road just visible on the map, near the narrow end of the triangle, will take you south to the graveyard. The map is cropped from Google Maps.

Selloo Cross Fragment

The Monastery

During an Archaeological Survey in County Monaghan in 1983 the monastic site at Selloo was examined by Anna Brindley. The site is composed of a nearly circular earthen bank that is about 100m in diameter. Near the center is a small burial ground enclosed by a wall. Records report the presence of a cross base at the site, but it was missing in 1983. What was found was a fragment of a free standing cross. (The diagram to the left is taken from Brindley, 1988, pp. 49-53)

Nothing seems to be known about the history of this site.

In the Archaeological Inventory of County Monaghan, compiled by Anna L. Brindley we find the following entry for Selloo, related to the site of the monastery from which the fragment came.

“1178 Selloo

“OS 8:11:5 (59.1, 21.9) ‘Children’s Burial Ground’ OD 200-300 H 5698, 3377

“Monastic Remains: Large, approximately circular area surrounded by low artificial scarp now only faintly visible and enclosing small sub rectangular area surrounded by boulder faced wall. Portion of decorated shaft of stone cross and parts of several quern-stones (all now in MCM), cross-base, bullaun stone and bones recorded from smaller enclosure.. (CR 1954, 63-64)

“SMR 8:11, 10-5-1983”

The Cross Fragment

The Cross fragment from Selloo is now housed in the County Museum in Monaghan. It is item #1983:63.

Brindley provides a detailed description. The photo to the right shows the front face of the fragment. “The shaft measures 18cms. (wdth) by 19cms. (thickness) and the fragment is 20cms. long. One of the edge mouldings is worn. The broken edges are parallel but diagonal to the shaft edges giving the panels a slightly trapezoidal appearance. This is fortuitous, however, as the panels themselves are quite regular. Decoration is confined to one side (henceforth termed the front face) and consists of interlace patterns contained within a moulded frame between edge mouldings. Parts of two panels are visible, one of which is represented only by the top of its frame moulding. The second panel is filled with a fretwork and interlaced pattern (angular and curving elements). This is too worn to allow full reconstruction but it is apparently comparable to the fretwork panel on the head of the Castledermont South Cross”

fragment is 20cms. long. One of the edge mouldings is worn. The broken edges are parallel but diagonal to the shaft edges giving the panels a slightly trapezoidal appearance. This is fortuitous, however, as the panels themselves are quite regular. Decoration is confined to one side (henceforth termed the front face) and consists of interlace patterns contained within a moulded frame between edge mouldings. Parts of two panels are visible, one of which is represented only by the top of its frame moulding. The second panel is filled with a fretwork and interlaced pattern (angular and curving elements). This is too worn to allow full reconstruction but it is apparently comparable to the fretwork panel on the head of the Castledermont South Cross”

"The reverse and sides show clear evidence that the shaft is unfinished and may have been abandoned due to an error of design. Parts of two panels are visible on the reverse; both are very irregularly scratched out and have not been completed. One of the horizontal lines was executed at an angle to the sides and subsequently corrected. This and some damage to the second panel may have led to the abandonment of the piece although, as both mistake and accident are shallow, it would have been possible to minimize both. The moulding on one side although outlined, is not completed, while the second moulding is outlined only on the reverse face and not on the adjacent face. This side face has been cut back except for a part of the centre; the other side face has not been cut back, is still rounded in profile as a result and projects beyond the edge moulding by 2cms. If completed, the finished width of the shaft would have been about 15cms. and not 18cms as at present.

The front face of the shaft is confidently executed and would, if completed, have compared favorably with some of the best known of the Early Christian period, in its disciplined use of mouldings to define the individual panels and to decorate the edges of the shaft. These elements occur on crosses of the 8th and 9th century.” (Brindley, p. 50)

Brindley’s comments about the unfinished nature of the fragment raises a question about whether the full cross was ever erected and displayed at Selloo. In this regard, it may follow the pattern of other incomplete crosses that were erected, such as the Unfinished Cross at Kells in County Meath.

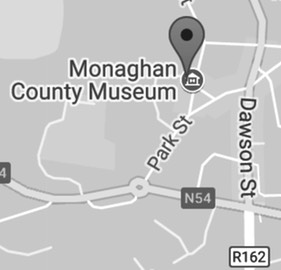

Getting There: On display in the County Museum of Monaghan in Monaghan town at 1 Hill Street. The map is cropped from Google Maps.

Resources Cited

Bigger, Francis Joseph, “Some Recent Archaeological Discoveries in Ulster”, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Section C: Archaeology, Celtic Studies History, Linguistics, Literature, Vol. 33 (1916/1917), pp. 1-8.

Brindley, Anna L., (compiler), “Archaeological Inventory of County Monaghan”, Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, 1986.

Brindley, Anna, L., “Early Ecclesiastical Remains at Selloo and Kilnahalter, County Monaghan”, Ulster Journal of Archaeology, Third Series, Vol. 51, 1988, pp. 49-53.

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Irish Archaeology: http://irisharchaeology.ie/2012/07/the-enigmatic-fulacht-fiadhburnt-mound/

“Life and Death in Monaghan”, Monaghan County Museum in Association with the National Roads Authority, 2003.

McCone, Kim, “Clones and Her Neighbours in the Early Period: Hints from Some Airgialla Saints’ Lives”, Clogher record, Vol. 11, No. 3, 1934, pp. 305-325.

McElherron, Brian T., photograph. http://stonecircle.bravehost.com/tours/2008/monaghanmiscellany/monaghanmiscellany.html

Moloney, Grace, “Old Donagh Church and Graveyard”, http://www.glasloughtidytowns.com/old-donagh-graveyard.html

Monastery Houses in County Monaghan: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_monastic_houses_in_County_Monaghan

Rootsweb: http://sites.rootsweb.com/~irlkik/ihm/ireclan2.htm, http://sites.rootsweb.com/~irlkik/ihm/colla.htm

Walsh, Fintan, “Neolithic Monanny, County Monaghan. http://www.tii.ie/technical-services/archaeology/publications/archaeologymonographseries/Mon-3-Ch-2-Walsh.pdf