This page contains information on the High Crosses of County Galway. They include: Addergoole; two cross-shafts and a cross-head at Killeany/Teaglach Einne; three cross fragments at Temple Brecan; and a Cross-head, fragmentary cross-head and cross-shaft at Tuam, and several crosses and cross fragments on St. Macdara’s Island. The location of County Galway is marked by the star on the map to the right.

Historical Background on County Galway

Human habitation in what is now County Galway began at least 7000 years ago around 5000 BCE. Evidence for this can be found in shell middens along the coasts.

Jumping ahead to the early Christian period, what is now County Galway was part of a collection of tribal dynasties that were collectively the Connachta, but not yet the province of Connaught. These various tribal dynasties claimed a common descent from the legendary Conn Cetchathach (Conn of the Hundred Battles). Conn was supposed to have lived in the second century of the common era and to have ruled Ireland as High King.

There were numerous tribal dynasties that were part of the Connachta during the early Christian period. Several, related to County Galway, are mentioned across a broad stretch of time from about 500 to 1100 CE. A few of the major groups include:

The Corca-Mruad, a dynasty that inhabited what is now the Burren in County Clare but also the area of Galway south and east of Galway Bay.

The Ui Maine, a dynasty that inhabited parts of the east and north of County Galway, spilling over into what is now County Roscommon and County Clare They are the forebears of the O’Kelly’s. .

The Ui-Fiachrach Aidhne who were located in south central County Galway in an area that is roughly the Diocese of Kilmacduagh. Later clans included the O’Heyne, O’Cleary, O’Shaughnessy, O’Cahill, the Kilkelly and others.

The Conmaicne who occupied parts of central County Galway and seem to have shifted to the west as the Conmaicne-Mara, from which we have the area of Connamara in extreme west Galway. Ruling tribes included the O’Cadhlas and the O’Flaherty’s.

The Ui-Bruine Sella, who were located in north central County Galway from about 700-900 CE. Their lands included the east shore of Lough Corrib. In the early 13th century they were forced into the Connemara peninsula where they were dominant for 400 years. The O’Flaherty’s are their descendants.

For a series of maps that show “Ireland’s History in Maps,” start with the following link: https://sites.rootsweb.com/~irlkik/ihm/ire500.htm For information on some of the early tribes click on “Old Irish Kingdoms and Clans” just below the maps.

Beginning in the late 8th century Viking incursions began in the area of present day County Galway. In 795 there were raids on Rathlin island off the northeast coast, Inishmurray off the coast of County Silgo and Inishbofin, off the western tip of Connamara. A raiding base was later established there. Around the same time raids were made in the area of present day Galway City in 807 and a base known as Roscam was established there.

Ecclesiastic History

There were numerous monasteries founded in the area of present day County Galway. Several were founded in the 6th century; including Cloghmore, founded by St. Colmcille; Clonfert, founded by St. Brendan; and Cloonfush, founded by St. Jariath. The Donaghpatrick monastery, supposed to have been founded by St. Patrick, may have predated the 6th century. A list of early monasteries, found in a “List of monastic houses in County Galway” is below. It will be noted that there is little information about many of these foundations. It is not clear that this list includes a monastery that was founded on the west end of Inishmore in the Aran Islands by St. Brecan at the same time that St. Enda founded a monastery on the east end of the island.

See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_monastic_houses_in_County_Galway

Addergoole Abbeyorder, period and foundation unknown, a high cross is present.

Ahascragh Abbeyearly site possibly founded by St. Cuan.

Annaghdown Nunneryearly site, Gaelic nuns, founded 6th century by St. Brendan for his sister Briga; became Augustinian nuns after 1144.

Ardahan Monasteryearly site with the stump of a round tower

Aughrim Prioryearly site prior to 741, later Augustinian Canons Regular

Caheradreen Monasteryearly site

Cloghmore Monasteryearly site founded 6th century by St. Colmcille

Clonfert MonasteryGaelic monks founded around 577 by St. Brendan the Navigator

Clonkeenkerrill Monastery early site

Clontuskert Prioryearly site founded about 805 by St. Boedan, later Augustinian Canons Regular, 12th century.

Cloonfush Monasteryearly site founded in early 6th century by St. Jariath

Donaghpatrick Monastery early site founded by St. Patrick

Drumacoo Monasteryearly site

Dunmore Prioryearly monastic site

Gortnabishaun Monastery early site

Gorumna Islandearly site

High Island Monasteryearly site founded before 665 by St. Fechin

Inchiquin Monasteryearly site founded before 626 by St. Brendan the Navigator

Inishark Monasteryearly site

Inishbofin Monasteryearly site, Gaelic monks founded 7th century by St. Coleman

Inisheer Monasteryearly site

Inishmaan Monasteryearly site, 2 churches in the parish of St. Enda on Inishmore.

Inishmicatreer Monastery early site

Inishmore Monasteryearly site, connected to St. Enda. High cross and round tower present on site.

Inishnee Monasteryearly site founded before 768

Kilbennan Monasteryearly site, Gaelic monks, founded by St. Benignus (Benen) a disciple of St. Patrick

Kilcolgan Monasteryearly site founded before 580, burned 1258

Kilcolgan Monasteryearly site founded in 6th century by St. Colmcille for St. Colgan

Kilcommedan Monasteryearly site

Kilconia Monasteryearly site possibly founded by St. Conlat.

Kilconnell Monasteryearly site founded by St. Conall

Kilcoona Monasteryearly site founded by St. Colmcille, built by St. Cuanna (Cuannach)

Kilcummin Monasteryearly site founded 6th century by St. Coeman

Kilkilvery Monasteryearly site

Killamanagh Prioryearly site

Killeely Monasteryearly site

Killeenmunterlane Monastery early site

Killower Monasteryearly site

Killursa Monasteryearly site founded by St. Fursa (Fursey)

Kilmacduagh Monastery, early site founded 6th or 7th century by St. Colman son of Duagh

Kilmeen Monasteryearly site

Kilreekill Monasteryearly site for nuns; founded by St. Patrick for his sister Rochelle

Kiltiernan Monasteryearly site

Kiltullagh Monasteryearly site possibly ended after 10th century

Kinvarra Monasteryearly site; patron St. Corman

Maghee Monasteryearly site, possibly in Co. Galway

Monasternalea Monastery early site

Omey Monasteryearly site founded 7th century by St. Fechin of Forew

Rafwee Monasteryearly site

Rathmagh Monasteryearly site founded 6th century by St. Brendan of Clonfert

Roscamfounded in 5th century and associated with St. Odran, brother of St. Ciaran of Clonmacnoise. Destroyed by Danes 807

Rosshill Monasteryearly site possibly founded by St. Brendan of Clonfert

St. Macdara’s Islandearly site founded by St. (Sionnach) Mac Dara. High Crosses are present on the island.

Tuam Monasteryearly site founded in 501 by St. Jariath. High Crosses are present.

With the reorganization of the church in Ireland that took place at the Synod of Rathbreasail in 1111 and later at the Synod of Kells in 1152 Tuam was given an archbishopric which included all or most of present day County Galway.

Addergoole Cross-Head

A cross-head is all that we have of what could have been a very large cross. The cross-head measures 55 inches (1.4m) in height and 50 inches (1.3m) across the arms. It is 15 inches (38CM) thick. It is located in the Addergoole or Carrowntomash graveyard near Dunmore to the north northeast of Tuam.

Cunniffe tells us that local tradition states that the cross was once a market cross but could also have served as a boundary cross. (Cunniffe) Harbison adds that the cross was moved from a quarried hill 100m west of its present site. (Harbison, 1992, pp. 9-10)

The cross is unfinished, the east face having no decoration. The west face has an unfinished crucifixion scene. The carving is irregular in shape.

Getting There:

See the Road Atlas page 24 E 5. Located north of Tuam between the N17 and N83 and south of the R328, just south of Garrafrauns. The cross head is now mounted in the southwest corner of the wall of the cemetery rather than being in the field to the west of the cemetery.

The map is cropped from Google Maps.

Resources Consulted

Cunniffe, Christy, http://field-monuments.galwaycommunityheritage.org/content/archaeology/crosses/addergoole-cross

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Killeany (Teaglach Einne)

The Site

Killeany is located near the east end of the island of Aran Mor. It was established about 485 by St. Enda, and may have been the first Irish monastery. Life at Killeany was rigorous. The monks lived in stone cells, slept on the ground, ate together in silence and conducted farming and fishing. It is said that Enda would not allow a fire to be lit in the monastery, so conditions must have been very cold much of the year.

In the photo to the left we see the base and shaft of a High Cross, the stump of a round tower and the shape of Teampall Bheanáin (St Benan’s Church) atop the ridge.

The monastery and monastic school Enda established is mentioned a few times in the Irish Annals between 655 and 1167. Viking raids are reported in 1019 and 1095 and it is stated that the monastery was burned once in 1020. (Manning p. 98)

In the 1650’s The stone of most of the monastic buildings was taken by Cromwell’s men and used to build fortifications. At the time of the Cromwellian destruction there were remains of six churches. Those destroyed were Kill Enda, Teampall MacLonga, Teampall Mic Canonn and St. Mary’s church. The latter may have been part of a Franciscan friary that once stood there. The buildings remaining are Temple Benan and Tighlagheany. Both of them were at some distance from the location where the fortification was built. (Manning, p. 96) While most of the monastery was sheltered from the worst of the wind and weather by the higher elevations of the island to the north and west, Temple Benan sits atop a limestone ridge above the harbor of Killeany.

The Saint

Legends of St. Enda vary in detail, but a few basics are common to most of the stories. Enda was a prince of Oriel in Ulster and may have become king when his father died. In his early life he was a warrior. He was later converted by his sister, Fanchea. It is said that she was a convert of St. Patrick. After his conversion he traveled, perhaps widely. Most sources suggest he went to Rome, where he was ordained. O’Maoildhia writes that “On his travels he was influenced by St. Martin of Tours, St. Honoratus on the Isle of Lerins, St. David in Wales and St. Ninian in Whithorn in Scotland.” (O’Maoildhia, p. 11)

In the course of time he returned to Ireland and established a church at Drogheda. Through another sister, Darina, he had Aonghus, King of Cashel as a brother-in-law. Through this connection he gained Aran Mor as a place to found a monastery. He arrived there about 485 with about 150 followers and established what is remembered as the first monastery in Ireland.

St. Enda died in about 530.

Cross Shaft and Base:

The cross shaft and base are located just below the remains of a round tower. The base is square and has a meander design on the south side.

East Face

E 1: “Interconnecting horizontal and vertical C-shaped spirals.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 126)

E 2: An equal armed cross divides the panel into four parts. In each is an animal contorted into a spiral shape.

E 3: Four squares of fretwork form a St. Andrew’s cross in the center.

E 4: Three pointed knots of interlace.

South Side

Bottom: A half-palmette emerges from a spiral.

Top: Interlocking vertical T-shapes.

West Face

W 1: This panel occupies the lower two-thirds of the west face. There are figures of 8. The inner strands move inward to spirals. The outer strands form trumpet shapes in the top corners and spirals at the bottom. In the bottom center is a knot of triangular interlace. (Photo to the right from Harbison, 1992, Fig. 421)

W 2: Two animals, back to back, have open jaws.

W 3: There is a very small indication of pointed interlace.

North Side

Bottom: Half-palmettes emerge from spirals.

Top: The decoration is unclear.

Shaft Fragments at Teaglach Einne

There are 3 fragments that have been placed together against a wall in Temple Enda. See the photo to the left.

North Face

Bottom: Pointed interlace is topped with a chain of interlace. This piece is displayed upside down and would have been located just above a crucifixion scene on the head as the very top of Jesus’ head is visible at the top of the fragment as it now stands. Reversed this panel looks like the photo to the right with the top of Jesus’ head at the bottom.

Middle: This fragment has a hooded horseman and above that a chain of interlace. This piece would originally have been just below the crucifixion scene on the head as the feet of Jesus are just visible at the top of the fragment as it now stands.

Top: A marigold pattern in a circle is above a partial field of irregular interlace.

South Face

Bottom: This piece is displayed upside down but is shown in its proper orientation in the photo to the right.

There is pointed interlace at the top and “below it, the segment of a circle composed of interlocking T-shapes.” (Harbison 1992, p. 127) At the very bottom is what appears to be the top of a head.

Middle: The lower portion of a figure in a long robe stands on a segment of pointed interlace. Photo to the left.

Top: The lower portion of the panel, as seen to the right, has four fretwork patterns that seem to form a St. Andrew’s Cross.

The upper portion has “interlocking horizontal and vertical C-shaped spirals.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 127)

East Side Photo to the left.

Bottom: undecorated

Middle and Top: Spiral and half-palmetto shapes.

Cross-Head from Teaglach Einne

This cross fragment was discovered during an archaeological excavation published in 1985 by Conleth Manning. (See Manning, pp. 118-119) The fragment consists of the upper arm, the central portion of the head and one arm. It measures .52m across by .50m high and .11m thick.

Face One: There is a partial crucifixion scene that includes Stephaton the sponge-bearer holding a cup rather than a sponge and the spear and head of Longinus. Longinus and Stephaton were carved on the arms. This is the only known instance of that in Ireland. (Manning p. 118)

Face One: There is a partial crucifixion scene that includes Stephaton the sponge-bearer holding a cup rather than a sponge and the spear and head of Longinus. Longinus and Stephaton were carved on the arms. This is the only known instance of that in Ireland. (Manning p. 118)

Face Two: This face is covered with design elements that include circular knotwork in the center, angular knotwork on the surviving arm and plate work on the upper arm. (The photos above are from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Figs. 427a left and 427b right)

The present location of the cross-head is not known and is under investigation.

The sides of the fragment and the end of the arm are undecorated.The illustration below left is from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 423. It illustrates how the cross shaft and three fragments in Temple Enda may have formed one complete cross. The cross-head found near Temple Enda was clearly from a second cross.

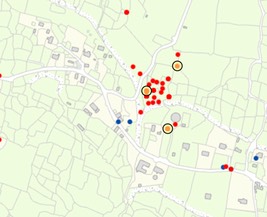

Getting There:

The Aran Islands are accessible by ferry. Killeany (Teaglach Einne) is located on Aran Mor, the largest of the Aran Islands. The site of the crosses described above is on the east end of the island, near the air field. The map marks the two locations with the large yellow and red circles.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Resources Consulted

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Manning, Conleth, “Archaeological Excavations at Two Church Sites on Inishmore, Aran Islands”, The Journal of the royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 115 (1985), pp. 96-120.

O’Maoildhia, Dara, Pocket Guide to Arainn: Legends in the Landscape, Aisling Arann, 1998.

Temple Brecan

On the west end of Aran More is a monastic site called Na Seacht dTeampaill, The Seven Churches. Present on the site today are two churches, a number of domestic buildings, some grave stones and cross inscribed slabs and fragments of three crosses. (O’Maoildhia, p. 81) The existing ruins date, at the earliest to the 12th or 13th century. Teampall an Phoill and the domestic buildings were built around the 16th century, suggesting that a European order had become established at the site. (O’Maoildhia, p. 93)

St. Breacan: Brecan arrived on Aran in the late 5th or early 6th century. This was about the same time as the arrival of St. Enda, who established a monastery on the east end of the island. Brecan was the son of a king and his monastery was originally called Diseart Bhreacain or Breach’s desert. (O’Maoildhia, p. 83)

St. Breacan insisted that he and Enda divide Aran Mor into two jurisdictions. They agreed that they would rise at dawn on a particular day, say mass and then walk until they met. Their meeting place would be the dividing line between their jurisdictions. St. Enda slept on a hill so he would see the sun as early as possible. St. Breach tried to cheat by riding a horse part of the way. Legend says that Enda saw this through his vision and put a spell on the horse so that it was pinned to the spot. (O’Maoildhia, p. 65)

St. Breacan is buried and his grave has a slab with his name inscribed on it. It is next to the Bed of the Holy Spirit that has the remains of the broken West Cross. The site became a pilgrim destination. (O’Maoildhia, p. 84)

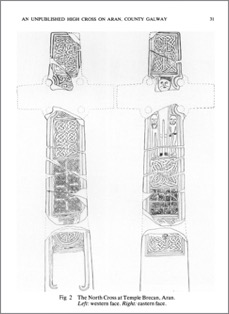

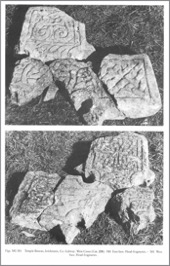

North Cross

Originally a limestone cross over 12 feet (3.7m) in height, only the stump of the shaft remains in position. As early as 1848 fragments were collected by Ferguson. They were uncovered again in 1973 by Waddell. The arms and parts of the shaft are missing. The photo below left shows how the fragments have been laid out. Waddell has described in some detail how these fragments had essentially been lost till he and his students rediscovered them in 1973. That they had been recognized as belonging together earlier is testified to by the fact there is a crude stone wall that surrounds the fragments. Macalister seems to have described the cross in 1928. Waddell notes that the carving is, for the most part, not done very well. (Waddell, pp. 29-30) The illustration below right shows how the pieces of this cross may have fit together. (Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 579)

The lower portion of the shaft is the only part standing.

East Face

E 1: Interlace with a triskele in the center circle.

E 2: Four key patterns form a St. Andrew’s Cross

E 3: Cross-shaped interlace

E 4: The Crucifixion

E 5: Interlace in the shape of a cross

West Face

W 1: Circular interlace with triangular interlace in the four corners.

W 2: Eight circular interlace designs

W 3 Six knots of interlace

W 4: Interlace

W 5: Interlace

Sides

The sides have no decoration.

The illustration above right from Waddell, p. 30.

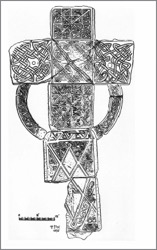

South Cross

The fragments of this cross have been cemented on a platform, leaving only one side visible. The illustration to the right is from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 576. The illustration was made by Westropp.

Head: Interlace forms four circular forms.

Arms: Two-strand interlace around a boss.

Above and below the head and on the upper panel there is fretwork.

Shaft: Westropp identified a crucifixion surrounded by ornament. This was no longer visible in the 1990’s.

Ring: The fragment of ring present has interlace.

West Cross

The remains of this cross consist of a partial shaft and a number of head fragments that are located nearby. The photo to the right is from Harbison 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 580-581. The west face of the head fragments is pictured above and the east face below.

East Face The photo is below left.

E 1: Four fret patterns form a St. Andrew’s Cross.

E 2: Four interlinked and circular interlace designs.

E 3: Two knots of pointed interlace.

E 4: Same as E 2.

Head: Circular interlace in the center. Interlace on the surviving arm.

West Face: The photo is to the right.

W 1: “Four circular devices apparently made up of two animals with heads meeting in the middle and biting each other. The space between them is filled up with an elongated three-point interlace.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 170)

W 2: Thick band of interlace.

W 3: Crucifixion scene with figures beside Jesus’ legs and under his arms.

The illustration to the left is from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 579 and was drawn by Waddell. The details of the crucifixion scene as shown in the illustration are much clearer than on the shaft, at least in the photos above.

Getting There:

The Aran Islands are accessible by ferry. Temple Brecan is located at the west end of the island in an area also known as Seven Churches. The locations of the three main crosses are indicated on the map by the yellow red circles. The north cross is away from the main enclosure of the site. There is a rusted sign that once marked its location. The cross pieces, except for a lower portion of the shaft that is upright, are largely overgrown. The South cross can best be found from the main road. There is a modern looking house visible on the north side of the road before you reach the Seven Churches road. If you go down this driveway, the cross is to your left about half way to the house.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

O’Maoildhia, Dara, Pocket Guide to Arainn: Legends in the Landscape, Aisling Arann, 1998.

Waddell, John, “An archaeological Survey of Temple Brecan, Aran”, Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society, Vol. 33 (1972/1973), pp. 5-27.

Waddell, John, “An Unpublished High Cross on Aran, County Galway”, The Journal of the royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 111, (1981), pp. 29-35.

Tuam Crosses

The Site

Human settlement at Tuam dates back to at least 1500 BCE. In the Christian period there was a monastery at Tuam from the early 6th century. The legend is that St. Jarlath (also known as larlaithe mac Loga) “was told by a vision, as interpreted to him by his friend St. Brendan, that he should leave the monastery at Cloonfush, and found a See where the wheels of his chariot broke down. (Kelly, p. 257) As it turned out, he ended up a mere 3 miles from Cloonfush where he started. An alternative story states that it was abbot St. Benin of Kilbannon who gave Jarlath the advice attributed above to St. Brendan. (The Tuam Guide)

In the 11th century Tuam gained prominence under the patronage of the O’Connor Kings of East Connacht, who established their capital there. In 1111 Turlough (Mor) O’Connor became High King of Ireland. He was a great patron of the arts and the high crosses of Tuam were produced during this time. Following the Norman invasion and the consequent reduction in the power of the O’Connor’s, Tuam lost its importance. After the first Cathedral was destroyed in 1184 Ruairi O’Connor left Tuam for Cong and gave the treasures of Tuam into the care of the abbot of Cong. (The Tuam Guide)

The Saint

Jarlath (also known as larlaithe mac Loga) was born of a prominent family in Connaught about 445 and died about 540. He is supposed to have studied under St. Benign (Benin) of Kilbannon, a disciple of St. Patrick. Later, he founded a monastery at Cluainfois (Cloonfush). He left Cloonfush around 495 to study with St. Enda of Aran. He returned, probably initially to Cloonfush, in the 520’s. Then, according to the story related above, he settled at Tuam where he founded a school and monastery.

The Crosses

The Market Cross

This cross is a composite formed by pieces of two different crosses. The base and shaft are from one cross and the head is from another. The base is just over 2 feet (60cm) in height. The shaft stands nearly 9.5 feet (2.9m) in height and the head is about 3.5 feet (1m) in height and a little wider across the arms than it is tall. Except where noted the descriptions below follow Harbison, 1992, pp. 175-176.

East Side

Base: The base is stepped with a plinth above the first step. On the area above the plinth are two panels of animal decoration. They are in the Urnes style, a Viking style often used on runic stones. Typically “animals are still curvaceous and one or more snakes are included with the quadrupeds.” (The Urnes Style) There is a socket between these panels that probably held a support for the original cross-head. (Harbison, 1992, p. 175)

Shaft: There are four panels and part of a fifth. All contain animals in the Urnes style.

Head: The underside of the ring has two panels of interlace flanking a panel of interlaced animal. The end of the arm has a figure in high relief.

South Face

Base: There is an inscription on the plinth that reads: “Prayer for Turlough O’Connor for the . . . of Iarlath by whom was made” (Harbison, 1992, p. 175) On the main face are two clerics in high relief. Urnes style animal interlaced flank the two clerics.

Turlough O’Connor (Tairrdlebach Ua Conchobair) was High King of Ireland from 1111 or 1128-1156. He was a patron of the arts. This, along with evidence from the inscription on the opposite side of the plinth (see discussion below) suggests a date for the carving of the cross between 1128 and 1150. (Tuam Guide)

Shaft: There are three panels of Urnes style and at the top a blank panel that has a mortise hole that may have held a now lost figure. (Photo; Harbison 1992, Vol. 2, Figs. 604-605, head Fig. 612)

Head: The Crucifixion shows Jesus against a cross with bosses above and below his hands. He appears to wear a crown. There is zigzag ornament beneath Jesus’ arms. Above Jesus’ head are two figures.

West Side:

Base: There is no inscription on the plinth and the main panels have animal ornament.

Shaft: There are four panels, each bearing Urnes style ornament. Part of a fifth panel is above.

Head: Under the ring a central panel of interlace is flanked by arches. Under the arm is a cheque pattern. The end of the arm has a bishop or abbot with a crozier who may be flanked by smaller figures. The photos to the right show the upper shaft and head above and the lower shaft below.

North Face:

Base: On the plinth is an inscription that seems to read: “Prayer for O Hossin, for the Abbot, by whom was made”. (Harbison 1992, p. 176) Urnes style decoration is on the panel above.

The inscription offers more evidence for dating the cross. O’Hoisin (O Hossin) became archbishop in 1150. In the inscription he is called abbot. He was abbot at Tuam as early as 1134 according to the Annals of Innisfallen. This suggests the cross was carved between 1134 and 1150. See the notes on the inscription on the south face above for more on the dating of the cross. (Petrie, pp.472)

Shaft: There are 4 panels. The lower one contains interlace, the other 3 have Urnes style interlace. The upper panel has animals arranged in the form of a cross. There is a square hole in the center.

Head: In the center of the head a bishop raises his hand in a blessing while holding a crozier in his left hand. On each side there are two small figures. Animal interlace is above the bishop’s head and what Harbison describes as “frills” are on the arms. A rectangular cut out is on the upper portion of each arm. (Harbison, 1992, p. 176)

Ring: There is moulding that encloses an undecorated panel. The moulding on the inner side terminates in animal heads.

Cross-shaft in Cathedral

This shaft was found beneath the communion table and has since been erected in the cathedral. It stands just under 5 feet in height. The panels are not separated by framing.

East Face Partial photo to the right.

E 1: Interlacing serpents.

E 2: Animal interlace forming four spirals.

E 3: Interlace forming four circular shapes.

E 4 and 5: Similar to E 3.

South Side Photo to the left.

An inscription covers the entire side. It reads: Prayer for the King, for Turdelbuch O’Conor. Prayer for the wright Gillu Christ O’Toole. (Harbison 1992, p. 177)

Based on the evidence above for the dating of the Market Cross, this cross must be essentially contemporaneous, dating to between 1128 and 1156.

West Face

W 1: Interlace for four circular shapes.

W 2: Four squares of fretwork.

W 3: Interlaced animals form a figure eight with an additional animal coiling around them.

Photo to the right.

North Side Photo to the left.

An inscription fills this side of the cross. It reads: Prayer for the successor of Iarlath, for Aed O Hossin who had this cross made. Like the inscription on the Market Cross this inscription supports the conclusion that this shaft is contemporaneous with the Market cross. Because it does not give O Hossin a table, the shaft could be a few years later than the Market cross as O Hossin became Archbishop in 1150.

Fragmentary Head of Sandstone Cross

This cross-head was found in the 1930’s. It consists of four pieces. It is 28 inches (61cm) high and 25 inches (60CM) across the arms. It has a ring that seems to encircle the head of the cross, though the arms may have originally extended farther. The head is perforate and is decorated with Urnes type animals intertwined with narrow ribbons that form an interlace on the ring. The opposite side of the cross is now without decoration, if any existed. (Harbison, 1992, pp. 177-178; photo Vol. 2, Fig. 618)

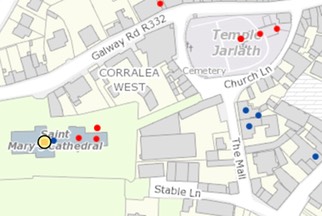

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 32 E 1. The crosses are located in St. Mary’s Cathedral in Tuam. The site is indicated by the yellow circle on the left-hand side of the map. The church is usually locked. Visiting for Sunday services would be an ideal way to see the crosses.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Kelly, Richard J., “Antiquities of Tuam and District”, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 34, No. 3, [Fifth Series, Vol. 14] (Sep. 30, 1904), pp. 357-260.

Petrie, George, “On the Stone Cross of Tuam”, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy (1836-1869), Vol. 5 (1850-1853), pp. 470-474.

Saint Iarlaithe mac Loga: http://slankamen.atwebpages.com/c.pl/439

St. Jarlath: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08323c.htm

The Tuam Guide, http://www.tuam-guide.com/history.htm.

Urnes Style: viking.archeurope.info/index.php?page=urnes-style

Saint Mac Dara Island

Saint MacDara Island is located off the south coast of Connemara. It was the site of an early Christian Ireland monastic establishment founded sometime in the 6th century, according to tradition. It was, of course, founded by St. Mac Dara, an early Irish saint who bore the name of his father. It is said that his own name was Sinach, which in Gaelic means “fox”. (Bigger, p. 102)

There are three crosses on the island with numerous fragments that have yielded another cross shaft and three fragments of a cross head, making a total of five crosses. Each of these crosses is described and pictured below.

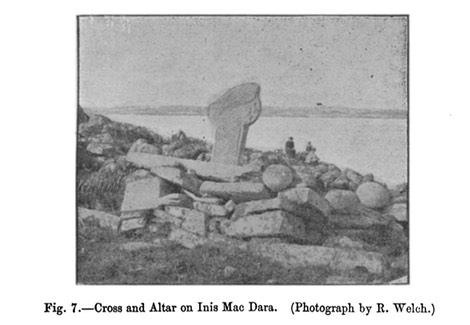

Cross on an Altar

What I will refer to as the Altar Cross is located on the northeast part of the island. It is pictured to the right. (Bigger, Fig. 7, p. 109) Crawford described this as “A rude cross, 3 feet (91cm) high, with an incised line following the outline; part of the top is broken.” (Crawford, p. 211)

Serpent Cross

The second cross, pictured to the left, has what Bigger described as serpents in the two lower segments of the head of the cross. It measures 30 inches (76cm) high, 17 inches (43cm) wide and 4 inches (10cm) thick. (Bigger, Fig. 8, p. 109) Crawford describes it as follows: “A plain limestone cross . . . with solid disk.” (Crawford, p. 211) Apart from the serpents, neither Bigger nor Crawford describe the rest of the carving on the cross. From the photo to the right it appears there is a crudely carved cross that occupies a raised circle around the head of the cross. In the center of the cross there is a boxlike figure with a raised boss in the center. This cross and the next are located south of the church.

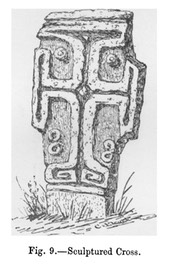

Sculptured Cross

This cross, pictured to the right measures 33 inches(83cm) in height and 17 inches (43cm) wide. Crawford describes it as “A granite cross, 2 feet 9 inches (84cm) above the ground (part being buried), with solid disk; carved with a double-lined cross in relief, and bosses on the east side and with circles, bosses, etc., on the west side.” (Crawford, p. 212) The arm to the right in the photo has the appearance of a rudimentary arm, extending slightly from the main body of the cross. The base tapers on both sides as it moves toward the base. (Biggers Fig. 9, p. 110)

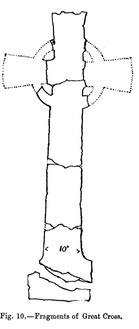

The Great Cross

Bigger identified several fragments of a cross that, when placed together, formed the central shaft of a cross. This cross, pictured to the left, was 7 feet 6 inches (2.3m) tall and 10 inches (25cm) wide. Based on the illustration to the right it was composed of five separate fragments. The illustration also suggests, based on what was present, what the cross may have looked like in its original form. (Biggers Fig. 10, p. 110)

Cross Head Fragments

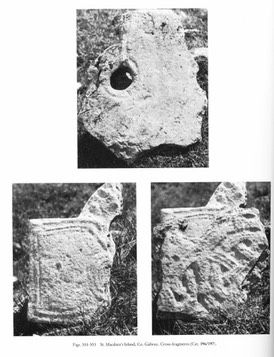

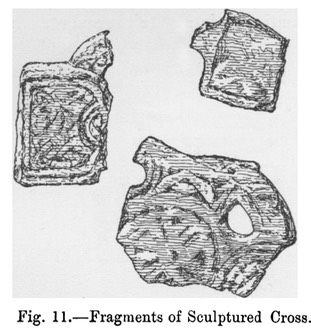

Harbison noted a grouping of two fragments that appear to have formed part of the head of yet another cross. These are illustrated in the photo below by the lower two photos on the right. Two of these fragments clearly include a two ribbed outline around the edges of the cross and an interlace pattern. Bigger included an illustration (Fig. 11, p. 111 below) of these two fragments with a third that he assigned to the same cross head. In addition, Harbison lists another head of a “ringed cross with small armpit holes, and with a roll moulding at the edges,” that is illustrated in the photo below in the upper photograph. (Harbison, 1992, Vol. 1 p 164, Vol. 2 Figs. 551-553)

Getting There

See Road Atlas page 29 D 3-4. The island is located southwest of Carna and can be reached only by boat. The best time to visit is on the pattern day on July 16, when fishermen take pilgrims to the island for free. Wear old clothes and Wellies.

The map is cropped from Google Maps.

Sources Consulted

Bigger, Francis Joseph, “Cruach Mac Dara, off the Coast of Connamara: With a Notice of Its Church, Crosses, and Antiquities,” The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 6, No. 2 (Jul., 1896), pp. 101-112.

Crawford, Henry S., “A Descriptive List of the Early Irish Crosses,” The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 17, Dublin, 1907.

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.