This page explores the High Crosses of County Tyrone. They include: Arboe, Caledon, Clogher, Donaghmore, Errigal Keerogue and Killoan. Where information is available there is a section on the history of the site, brief information about the primary saint related to the site and a description of the cross or crosses at the site. Except where noted, the photographs were taken by the author. Directions to the sites reference The Official Road Atlas Ireland. Maps related to the sites are cropped from Google Maps.

This page begins with a sketch of the history of the area that is now County Tyrone from the Mesolithic Age to about 1200, the end of the Early Christian Age and of the period of the Irish High Crosses.

Beginning just prior to the Christian period, Tyrone was the stronghold of the O'Neill clans. The name Tyrone is a development of the Irish Tír Eoghain, the land of Eoghain, a son of Niall of the Nine Hostages who reportedly died in the early 400’s of the common era. The Ui Neill expanded from what is now Donegal and became the strongest of the clans in Ulster throughout the early Christian period.

The Mesolithic (7500 to 3200 BCE)

Human habitation of Ireland dates to the middle of the eighth millennium BCE, according to M. J. O’Kelly in “Ireland before 3000 B.C.” in A New History of Ireland: Prehistoric and Early Ireland, edited by Daibhi O Croinin. O’Kelly wrote “that mesolithic settlement in the country was not confined to the north-east but extended to most areas of the island, to the midlands, the west, and the far south.” O’Kelly suggests that an early mesolithic period lasted from about 7500 to 6000 BCE with a later Mesolithic period dating from about 5500 to 3200 BCE. (O’Kelly, p. 65) Evidence for human habitation has been established largely through discovery of flint tools. (O’Kelly, pp. 58-65) It is possible that some flints found at Beaghmore, discussed below, may date from the Mesolithic period.

Neolithic Age (4000-2500 BCE)

The late Mesolithic and the early Neolithic overlap. M. J. O’Kelly, in “Neolithic Ireland” in A New History of Ireland, describes an excavation at Ballynagilly, in County Tyrone as offering important evidence “of early neolithic activity in Ireland.” This site, excavated between 1966 and 1971 contained “a rectangular house 6.5m x 6m, marked by foundation trenches and postholes. . . . Radiocarbon dates . . . average between 3700 and 3800 bc.” The area was used for pasture rather than planting grain. (O’Kelly p. 69)

Elsewhere, referring to the Neolithic period in Ireland in general, O’Kelly remarks that by the early fourth millennium BCE agriculture was being practiced in Ireland. This would have included the growing of wheat and barley. (O’Kelly, pp. 69 and 71)

County Tyrone is the focus of a series of stone circles, cairns and stone rows that stretch across Counties Fermanagh, Derry and Tyrone. The bulk of the sites (about 80%) are found in County Tyrone. One of the best examples is at Beaghmore. The name Beaghmore means “the moor of the birches.” While the circles and rows seem to date to about 1600 BCE, the Bronze Age, there is also evidence of hearths and flint tools that date to the late Neolithic Age (2900-2600 BCE). In addition, some stone rows run over field walls that also date from the Neolithic period. (Beaghmore) The presence of field walls might indicate that the folk at Beaghmore were engaged in agriculture.

Another site of note is the Knockmany Passage Tomb. While the passage is missing, some of the upright stones are decorated with “characteristic passage-grave art, including circles, spirals and zigzags.” (Coyle) The site has been dated to 3000-2500 BCE. Below left is an illustration of the passage grave from The Little Book of Tyrone, by Cathal Coyle. (Coyle)

Yet another County Tyrone passage tomb is Sess Kilgreen. It has some of the best neolithic rock art in Ulster. An illustration from The Little Book of Tyrone is shown above right. (Coyle)

The Bronze Age (2500 to 500 BCE)

As noted above, human occupation, in what is now County Tyrone, continued in the Bronze Age. It was then that the stone circles, cairns and stone rows were placed at Beaghmore. These almost certainly had a ritual purpose. (Beaghmore) Thus, what is now County Tyrone must have had a settled population engaged in farming and animal husbandry that continued from the Neolithic period. The photo below shows portions of the Beaghmore complex.

“A total of seven circles, six of which are paired, were discovered, along with many cairns, some of which have associated stone rows. A typical feature of the Beaghmore stone rows is a "high and low" arrangement where short rows of tall stones run beside much longer rows of small stones.” (Beaghmore)

M. J. O’Kelly, in “Bronze-Age Ireland”, notes that about 2000 BCE a new type of pottery arrived in Ireland. This was beaker ware. This seems to have marked a shift into the Bronze Age. O’Kelly writes: “the Beaker people are credited with having had close association with the knowledge of, and the search for, metal. . . . . It has been suggested that the Beaker folk came to Ireland as prospectors and miners looking for suitable copper lodes to exploit.” (O’Kelly pp. 100-101)

The Iron Age (500 BCE to 400 CE)

The exact dates for the Iron Age in Ireland are debated. We will assume the dates listed above. The early date represents the time period when Celtic peoples began to move into Ireland. It is believed they brought iron technology with them.

The Iron Age in Ireland has been referred to as a dark age related to archaeology in Ireland. In an article entitled “Iron Age Ireland: Finding an Invisible people”, Becker, O’Neill and O’Flynn report some results from the 2008 Archaeology Grant Scheme. They write:

“Until recently, knowledge of Iron Age Ireland was largely restricted to an artefact record which is biased towards the north of the country; a limited burial record; and’ a small but significant, group of specialised monuments: the so-called Royal sites. However, very little is known of the vernacular culture of the Irish Iron Age, particularly, where and how people lived, the types of houses they built and their industrial activities.” (Becker p. 1)

The work carried out related to the 2008 Grant Scheme identified 240 Iron Age sites. (Becker p. 19) A general description suggests that “A range of different types of evidence for Iron Age vernacular life could be identified. These site which provide the previously lacking evidence for settlement and industry in this period, range from possible house or workshop structures and enclosures to fulacht fiadh, troughs and trackways.” (Becker p. 20)

A characteristic structure of the Iron Age was the hill fort. In County Tyrone at least eight hill forts and contour forts have been identified. For example, at Mallabeny, a townland in County Tyrone there is a hill fort that covers a circular area at least 100m in diameter that is surrounded by a bank that was up to 2m high. (Mallabeny)

In a two volume work entitled “The Social the Technological Context of Iron Production in Iron Age and Early Medieval Ireland c. 600 BC - AD 900”, Brian Dolan dates the Early Iron Age in Ireland to as early as 700 BCE. He describes one site in County Tyrone that exhibits evidence of Late Iron Age and Early Medieval iron work. This site was described as “A multi phase site with extensive prehistoric activity in a mound subsequently re-used as an enclosure with two distinct phases, both with evidence for ironworking. The later phase, Layer 3 was represented by a cobbled occupation surface extending over the entire site with the same limits as phase 1. A low stony bank with no ditch was identified which enclosed the site. Very little evidence for domestic occupation was recovered.” (Dolan, Vol. 2)

The Early Christian Period (400 to 1000 CE)

This period of time in Ireland is obviously named for the arrival of the Christian faith. This new faith gradually became the dominant religion of the Emerald Isle.

Political Background:

Tradition tells us that Niall Noigiallach (of the Nine Hostages) became King of Midhe (Meath) around 400 CE. Around this time the Ui Neill’s divided with the Cenel nEoghain and Cenel Conaill occupying the northwest. They became known as the Northern Ui Neill. Others followed Niall of the Nine Hostages into Meath where they came to be know as the Southern Ui Neill.

Niall of the Nine Hostages and his sons originally moved north and east from Connachta in the West. The Ui Neill in the north eventually dominated an area including counties such as Donegal, Derry and Tyrone. By 500 CE this group were know as the Northern Ui Neill and they were expanding east into the territory of the Ulaid in northeast Ireland. By about 600 CE the Northern Ui Neill had two main groups; the Cenel Conaill to the west and the Cenel nEogain to the west. By about 700 CE they held all or most of what is present day County Tyrone. Through at least 1000 CE the Northern Ui Neill continued to expand to the south and east. (Rootsweb)

The Cenel nEoghain take their name from Eogan, son of Niall of the Nine Hostages. With three brothers, Conall Gulban, Enda and Cairbre, he overthrew the Ulidian power in the northwest and became King of Ailech, a hill fort at the base of the Inishowen Peninsula that bears Eogan’s name. Their territory came to be called Inis Eogain, Eogain’s island. This is dated to about 425. It is said that Eogan was converted to Christianity by St. Patrick, perhaps about 442. The Cenel nEogain overcame the dominance of the Cenel Conaill, their cousins, in the mid to late 8th century. By around 800 the kingship of Tara alternated between the Cenel nEogain and Clann Cholmain of the Southern Ui Neill. Gradually, the Cenel nEogain advanced into the territory of the Airgialla and Ulaid. Their territory eventually included what is now County Derry and County Tyrone. In fact the name Tyrone derives from Tir nEogain or the land of Eogan. This expansion took place during the 10th and 11th centuries. As the Cenel nEogain advanced to the east they gained influence over the religious center of Armagh.

After about 1000, the power of the Northern Ui Neill and Cenel nEoghan, began to wane. For example, the Ua Dochartaig (O’Doherty) forced the Cenel nEogain out of Inishowen and the Mag Uidhir (Maguire) became dominant in in Fir Manach (Fermanagh).

The Cenel Conaill were the descendants of Conall Gulban who ruled in Tir Connell, the land of Conall, the area of modern County Donegal. It was this branch of the Ui Neill that produced St. Columba and subsequently provided Abbots for the Iona monastery from 563-891 or later. The Cenel Conaill were, the dominant branch of the Northern Ui Neill during the 6th to the late 8th century, as noted above.

There were other branches of the Northern Ui Neill. These included the Cernel Cairpre and the Cenel nEnnai.

Having related the traditional story of the Northern Ui Neill, it is important to relate another reading of the story. Brian Lacey, in Cenel Conaill and the Donegal Kingdoms AD 500-800, in a chapter entitled “The ‘Ui Neill of the North’: a genealogical fabrication” outlines this alternative story. “To sum up, with the exception of Cenel Cairpre, there appears to be no evidence that any of the rulers of the Donegal kingdoms were related by blood to Niall Noigiallach or to the Ui Neill. Instead, it seems that there is evidence that the Cenel Conaill were a Cruithin people associated in some way with the Ui Echach Coba and with other, allegedly, east Ulster peoples. The Cenel nEnnai may have had connections with the Cruithin Dal nAraidi or, alternately, with the Airgialla, who, themselves may originally have had connections also with the Cruithin. The Cenel nEogain, but a lot less certainly, may have had connections with the Dal Fiatach. The paradox in all of this is, that, of the groups said to have belonged to the northern Ui Neill, the one that would become most marginalized, the Cenel Cairpre, may have been the only genuine one among them.” (Lacey, p. )

Ecclesiastical History

As noted briefly above, St. Patrick was active in the areas of the Cenel nEoghan and Cenel Conaill from some time in the mid 5th century. Eogan, the king of the Cenel nEoghan at the Grianan of Aileach, a hill fort at the foot of the Inishowen peninsula and capital of the Cenel nEoghan, was baptized by St. Patrick around 442. Tradition states that Patrick founded a church in Ard Macha (Armagh), in what is now County Armagh, in 445. From that time, the church at Armagh was considered by its supporters to be the principal church in Ireland. As noted above, the Northern Ui Neill eventually had great influence over the Armagh church. St. Patrick, of course, became one of the three patron saints of Ireland.

Another of the patron saints of Ireland was St. Columba. As noted above, he was, by tradition, a member of the Cenel Conaill. Columba lived from 521 to 597. He established the monastery at Iona in Scotland in 563. The Cenel Conaill provided Abbots for the Iona monastery from 563-891 or later.

As in all the counties of Ireland, numerous monasteries were established in what is now County Tyrone. The following is a list of early monasteries in County Tyrone. (List of Monastic Houses, Tyrone)

Ardboe Monastery,early site, founded late 6th century

Ardstraw Monastery, early site, founded by St. Eugene

Ardtrea Monastery, early site, nuns, founded by St. Trea

Bodoney Monastery, early site, founded 5th century by St. Patrick

Cappagh Monastery, early site, patron St. Eoghan

Carrickmore Monastery, early site, founded by St. Columba

Clogher Abbey,early site, founded 5th century by St. Patrick

Clonfeacle Monastery, early site, founded pre-597, Culdees

Donaghanie Monastery, early site, founded by St. Patrick

Donaghedy Monastery, early site, patron St. Ciadnus

Donaghenry Monastery, early site, founded by St. Patrick

Donaghmore Monastery, early site, founded 5th century by St. Patrick

Dromore Monastery, early site, nuns, founded by St. Patrick

Drumragh Monastery, early site, patron St. Columcille

Dunmisk Monastery, early site, founded by St. Patrick

Errigal Keerouge,early site, patron St. Ciaran, founded pre 506 by St. Macartin

Glenarb Monastery, early site

Kilskeery Monastery, early site, founded 749

Leckpatrick Monastery, early site

Longfield Monastery, early site

Magheraglass Priory, early site, founded 6th century by St. Columcille (?)

Omagh Monastery,early site, founded about 792 (?)

Termonamongan,early site, founded 6th century, patron St. Caireall

Termonmaguirk,early site, founded by St. Columcille (?)

Trillick Monastery,early site, founded by 613

Of the twenty-five sites listed above, seven are attributed to the work of St. Patrick. It is clear from the Tripartite Life that Patrick was active in this part of Ireland. Four monasteries are attributed to St. Colum Cille, who was active about a century after St. Patrick. There was competition between the paruchia of Patrick and that of Colum Cille in the 6th and 7th centuries. The paruchia was the collection of churches and monasteries that held a particular leader as their patron. An example of this rivalry is narrated in the Tripartite Life. It is noted in relationship to the Ardstraw (Ard-Sratha) monastery that “to Patrick belongs the church, upon which the people of Colum-Cilloeand of Ard-Sratha have encroached.” (Tripartate Life, p. 65) As noted above, Ardstraw is located in County Tyrone. The Ardstraw monastery, as listed above, is attributed to St. Eugene (Eoghan), rather than St. Patrick. St. Eugene (Eoghan) died in 618. This means that if Ardstraw was founded by St. Eoghan, it was founded in the late 6th or early 7th century. (Parish of Ardstraw east)

Writing in the seventh century, Tireachan, in the Collectanea, claimed that Patrick ordained Mac Erca as bishop of Ard Sratha, making it subject to Armagh. This would suggest that St. Patrick actually established the church/monastery there. This claim reflected the situation in Tireachan’s time, when Armagh was trying to extend its power and influence. The Parish of Ardstraw east states this actually suggests that in the seventh century, Ardstraw was independent. This background makes it difficult to say when or by whom Ardstraw was founded. What we do know is that the lives of St. Colum Cille and Eoghan overlapped and that Ardstraw at some point, perhaps in the seventh century, came under the influence of the paruchia of Colum Cille.

Of the early monasteries listed above, Ardboe, Clogher, Donaghmore, Errigal Keerogue and Glenarb have high crosses. In addition there is what may be the shaft of a high cross at Killoan. Background on each of these sites and descriptions of the crosses can be found in “The High Crosses of County Tyrone” as indicated in the Sources Consulted.

Arboe

This feature includes an Introduction to the Site and the Saint and an Overview of the Cross.

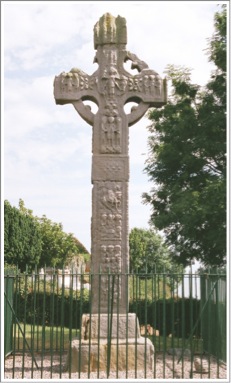

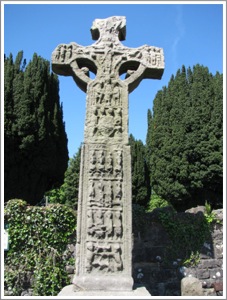

“The cross at Arboe is unusually tall, standing some 20 feet high. It is profusely decorated by abstract motives and by a comprehensive series of figure sculptures which are treated with exceptional detail and fullness. The balance between form and decoration, between ornament and narrative: the delicate execution of the abstract design contrasting with the robust and lively realism of the figure sculpture, all combine to set this cross amongst the most distinguished of the Irish monuments.” (Helen M. Roe, p. 81)

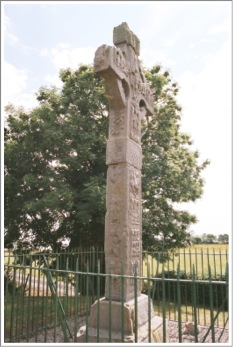

The photo to the right shows the east face of the cross.

The Site

Basic information about the monastery at Arboe (also spelled Ardboe) can be found in a letter from William Reeves, the Rector at Tynan in County Armagh to a C. Treanor at Ardboe. The letter is dated 30 November 1869.

“My Dear Sir, I myself made a pilgrimage many years ago to the old Cross of Ardboe, when I was fresh in the incumbency of Ballymena, ere my tastes had broken out in a love for antiquities.

“I copy all that is said about it in Archdale’s Monasticon.

“‘In the Barony of Dungannon, and two miles west of Lough Neagh, a noble celebrated monastery was founded here by St. Colman, the son of Aid, and surnamed Macaidhe; his reliques were being preserved in the Abbey, and Festival is kept on the 21st February.

“‘A.D. 1105. Monchad O’Flarthican, Dean of this Abbey, and a doctor high in esteem for his wisdom and learning, died in pilgrimage in Armagh.

“‘A.D. 1166. Rory MaKany Mackillwarry Oilloona did so destroy this Abbey by fire that it immediately fell to decay, and was scarce visible in the time of Colgan the Franciscan.’” (Bigger and Fennell, p. 2)

The citation of the death of Monchad O’Flarthican is actually listed in the Annals of Ulster under the year 1103. It reads “Murchad ua Flaithecán, superior of Ard Bó, eminent in wisdom and honour and teaching, died happily on his pilgrimage, i.e. in Ard Macha. (Annals of Ulster, 1103)

The mention of the destruction of the Abbey appears both in the Annals of Ulster and Annals of the Four Masters. The citation in the Annals of Ulster reads “And Ard-bo was burned by Ruaidhri, son of Mac Canai and by the son of Gilla-Muire Ua Monrai and by the Crotraighi.” (Annals of Ulster 1166)

The photo to the left shows the west face of the cross.

The current Parish of Ardboe has a website that offers a brief history of the parish. It traces the conversion of the people of the area, the Ui Turitre clan by Saint Patrick. Legend has it that he converted Cairthen Beg, the leader of the clan. About a century and a half later Colman MacAidh, great-great grandson of Cairthen Beg founded an abbey at Ardboe. The history continues “there can be no doubt that the Abbey of Ardboe was a seat of learning and instruction; indeed it thrived for almost six hundred years.” (parishofardboe.com)

Following the destruction of the Abbey in 1166 it was not reestablished. The brief history states “its destruction coincided with reforms put in place by St Malachy, Archbishop of Armagh, to replace Ireland’s monastic system by parishes and dioceses. Subsequently the townlands of Ardboe became a parish in the deanery of Tullyhogue, in the diocese of Armagh.” (parishofardboe.com)

For four hundred and forty years after its destruction the parish continued and the Gaelic way of life continued for its members. In 1607, as a result of the creation of the Plantation of Ulster, the native Irish population was dispossessed and the church became the property of the new settlers. (parishofardboe.com)

The lovely photo below, taken by Kenneth Allen, was found on the internet. Attribution is below in the References section. This shows the east side of the site with the ruins of an old church to the right and a view of Loch Neagh to the left.

The Saint

Legend tells us that Arboe was founded by a Saint Colman. However, there are at least 130 saints named Colman mentioned in the Irish Martyrologies and Histories.

The Colman who is celebrated at Ardboe, as founder of the monastery there, has been identified with Saint Colman, surnamed Mucaidhe. A genealogy identifies him as son of Aid, son to Amalgad, son of Muredach, son to Carthenn, son of Erc, son to Ethac or Eochod, son of Colla Huasius, King of Ireland. (omniumsanctorumhiberniae.blogspot.com) This follows the genealogy offered by the Parish of Ardboe website in claiming Colman was related to the royal family of his clan. The Carthenn mentioned above would appear to be the same person the Parish website names as Cairthen Beg. It is well known that many of the saints of Ireland had connections to royal families. Colman was apparently a member of this group.

The Cross

The cross at Arboe stands 5.70 meters or just over 18 and a half feet tall. It is one of the tallest in Ireland. It stands on a stepped base. Taken together the two levels of the base are 3 and a half feet tall. The cross is constructed of four pieces of red sandstone.

The top stone fell in about 1817. The upper portion, including the arms fell in 1846. Restoration took place between then and late 1850. It was managed by Colonel Stewart of Killymoon and the cross was apparently moved in the process. (Bigger and Fennell, p. 1)

Colonel William Stewart of Killymoon was born in 1781 and died in late 1850. He was a Colonel in the Tyrone militia and served in the Dublin and Westminster parliaments for Tyrone. He and his family were members of the Protestant Acendency.

(http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/member/stewart-william-1781-1850)

The upper parts of the cross are quite weathered. For our purposes the cross can roughly be divided into four parts. 1) the shaft, 2) a wider band of decoration near the top of the shaft, 3) the head above the band and 4) the house or church shaped cap.

The East Face

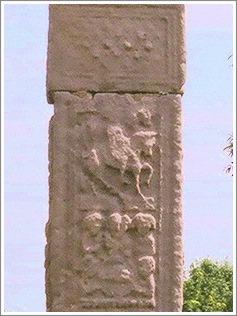

The shaft is composed of four panels. The lowest of these panels represents the Hebrew scripture story of Adam and Eve in the garden after they have eaten the forbidden fruit and suddenly see themselves as naked. (Genesis 3)

In the scene the tree stands between them and arches over their heads. On the trunk of the tree the serpent is visible and is turned toward the left hand figure, presumably Eve. Both Adam and Eve have their hands lowered to cover their genitalia.

(Photo to the left from Harbison, 1992, vol. 2, figure 31)

The next panel up represents the Hebrew scripture story of Abraham’s near sacrifice of his son Isaac. (Genesis 22:1-19)

Both Peter Harbison and Helen Roe describe this scene in some detail. In general what we see is Abraham on the left. In front of him Isaac bows over an altar. He appears to bring the wood for the sacrifice with him in the foreground. Above Isaac’s back is the figure of the ram and above and to the right of the ram is an angel. Roe describes Abraham as “bearded and clad in a belted tunic, hold[ing] a cleaver-like weapon. It is not clear if he grasps Isaac’s hair with his other hand.” (Roe, p. 82)

Harbison describes Abraham standing “upright on the left, dressed to the knees and wearing an over-garment. His right hand is placed across his breast, while his left holds up the sword diagonally.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 15)

Roe describes the angel in the upper right of the scene as “thrust[ing] in the ram.” (Roe, p. 82) Between their two descriptions we have a reminder of just how difficult it is, even for those who have studied the crosses most deeply, to discern the details of the image. This is more difficult on a sandstone cross like Arboe that has suffered so much deterioration from weather.

The third panel up depicts the story of Daniel in the Lion’s Den. (Daniel 6:10-28)

The figure of Daniel is in the center of the panel. He seems to be clothed to the knees and to have an overgarment that comes to below the waist. Roe also describes him as having “a heavy mustache and short beard.” (Roe, p. 82) His hands are stretched out to the sides so that he has a kind of cruciform shape. His posture is best understood as an orant posture. Following is part of what the Encyclopedia Britannica has to say about this posture.

“In Christian art, a figure in a posture of prayer, usually standing upright with raised arms. The motif . . . is particularly important in Early Christian art (c. 2nd-6th century) and especially in the frecoes and graffiti that decorated Roman catacombs from the 2nd century on. Here many of the characters in Old Testament scenes of divine salvation of the faithful, the most commonly represented narrative subjects of the catacombs, are shown in the orant position. . . .The orant has been interpreted as a symbol of faith or of the church itself.” (http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/430996/orant)

It is clear from the text of Daniel that deliverance was a major theme of this story. When Daniel is initially placed in the lion’s den, Darius the king says “may your God, whom you faithfully serve, deliver you!” (6:16b) When Darius returns in the morning he calls out “ Daniel, servant of the living God, has your God whom you faithfully serve been able to deliver you from the lions?” (6:20b) Daniel replies that angels have protected him.

On either side of Daniel is a lion raised up on hind legs, tail twisting around its legs, facing Daniel with its jaws open and its tongue reaching out toward Daniel.

The fourth panel up represents the story of the story of the Fiery Furnace. (Daniel 3:19-30)

Details are difficult to make out due to weathering. Harbison describes the image in this way: “The three children — two of them kneeling on one knee and facing one another in profile, and the third, much smaller, frontally between them — are protected by the outspread wings of the angel. On either side of the angel’s head, four flames curl upwards above the horizontal frame at the top of the panel.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 16 and the photo to the right Vol. 2, figure 31)

Bigger and Fennell, writing in 1897, are the lone voices suggesting another, but unlikely, interpretation of the panel. They describe it as an image of the Ark of the Covenant being carried along. They do not offer a detailed analysis of the image and that makes it problematic to assess their interpretation.

The Ark of the Covenant is mentioned numerous times in the Hebrew scriptures. The construction of the Ark is described in Exodus 25 and 37. A section of the text that may have influenced Bigger and Fennell reads as follows: “The cherubim spread out their wings above, overshadowing the mercy seat with their wings. They faced one another, the faces of the cherubim were turned toward the mercy seat.” (Exodus 37:9) The image to the left offers an interpretation of what the Ark of the Covenant may have looked like. (http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Judaism/ark.html is the source of the artists rendering)

The story of the Fiery Furnace follows the themes of the Sacrifice of Isaac and Daniel in the Lion’s Den better than the Ark of the Covenant.

The band of decoration that tops the shaft is pictured to the right. The full design in difficult to make out. What is obvious is that the whole is framed by moulding. Within is a second framing feature described as a line of pellets. The interior design can be described as "a panel of rather wiry spirals with fret.” (Roe p. 82)

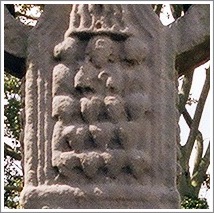

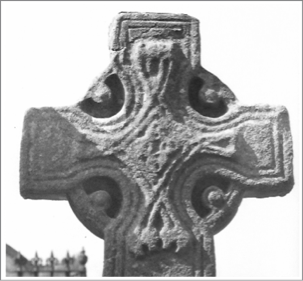

The head of the cross begins with a panel just above the band that has proved to be difficult to identify with any precision. Both Roe and Harbison agree on the content of the scene. At the top, in the center, is a bust of Christ. He is identified by the crook in his left hand. On each side of this figure are the busts of angels. Below are eleven figures, identified as the eleven apostles (the twelve minus Judas). See the photo to the left.

Harbison identifies this scene as the second coming of Christ. Roe identifies it as Christ with the apostles. Harbison informs us of a variety of other interpretations: Bigger and Fennell, the Resurrection; Henry the Transfiguration or part of the Last Judgment; Flower, a monastic leader and community at the Judgment. (Harbison, 1992, p. 16)

If this represents a specific text, what text might that be? The only one that seems to come close to fitting is that of a resurrection appearance. In Matthew we read “but the eleven disciples went into Galilee, to the mountain where Jesus as directed them. When they saw him, they worshipped him; but some doubted.” (Matthew 28:16) Jesus then gives his disciples the Great Commission. The eleven surviving apostles and Jesus are accounted for in this scene. The angels accompanying Jesus are not mentioned in scripture but are typically present in high cross art depicting the crucifixion, for example. This interpretation bridges the interpretations of Bigger and Fennell and Roe by suggesting this is a resurrection appearance of Jesus with the apostles.

The center and arms of the cross contain a scene identified as either Christ in Glory or the Last Judgment. As seen in the photo below left, the figure of Christ is in the center. He stands upright, clothed in a long robe, holding a cross in his left hand and perhaps a secptre in his right. He is surrounded by an indeterminate number of heads on his left and right and possibly above him. The head of the cross is badly eroded. Below the feet of Christ is an image of a scales. Below that are flames. These features suggest that the scene reflects the Last Judgment. A similar, but more detailed scene appears on the head of Muiredach’s cross at Monasterboice in County Louth. In this image (below right) it is clear that the figures on the left are moving toward Christ while those on the right are moving away. They represent, respectively, the saved and damned. Whether this was true of the image at Arboe is not clear.

The South Side

The Shaft: The following describes the decoration of the south side of the cross below the ring.

The lowest panel represents Cain killing his brother Abel. The story is found in Genesis 4:1-16. Like the image of Adam and Eve on the east face of the cross, this image represents fallen humanity. (The image to the right is a detail found in Harbison 1992, vol. 2, figure 34) In the image, Cain appears to kill Abel with a cleaver or machete type instrument.

The next two panels, moving up the shaft, are closely related. They both come from the story of David and Goliath. The lower of the two shows David subduing a lion and rescuing a lamb. The text is found in I Samuel 17:32-37. This is a story David tells King Saul to convince him that he (David) is capable of subduing Goliath. In the image we see the lion in the lower part of the panel with David to the left reaching down and grasping the jaws of the lion. Above to the right is a lamb and there may be another lamb below the lion.

The upper panel carries on the story. Saul sends David out to fight Goliath. The text is found in I Samuel 17:38-52. David is on the left and Goliath is on the right with a round shield on his left arm. Goliath is on his knees before David. Roe and Harbison agree that David’s sling is hanging from his hand and that Goliath has his right hand on the wound in his head. (Roe, p. 82; Harbison 1992, p. 16)

Here we have two more images of deliverance.

The fourth panel changes the theme away from the Hebrew scriptures to the tradition of the Desert Fathers, a popular theme for the churches of Ireland. It is relatively easy to pick out the figures of the two saints. They are seated side by side. Above there is a descending bird. What is more difficult to make out is that each of the saints has a staff with a crooked head that appears above their heads. Also difficult to make out clearly is that the bird carries a loaf of bread to the saints. This image appears on a number of crosses, including the north cross at Castledermot.

The story is that Saint Paul the Hermit was the first to live alone in the wilderness. For seventy years he lived in a cave, wore a tunic made from a palm tree fiber and saw no one. His meals were send to him by God via a raven. Each evening he received half a loaf of bread. When Saint Anthony, another of the early desert fathers, learned about Saint Paul, he immediately went to find him. When Anthony found him he was greeted with hospitality and the two talked about the greatness of God. In the evening the raven appeared. The bird carried not a half loaf of bread but a full loaf, half for each of the two saints. The story is intended to emphasize the holiness of both of the men. (CopticChurch.net, 1998-2005, http://www.copticchurch.net/synaxarium/6_2.html)

The band and the area above it are dedicated to decoration. Both panels feature bossed spiral design. That on the band is described by Roe as having “foliate links.” (Roe, p. 83) In this case the bosses are located in the four corners of the panel.

In the panel above the band there are also four bosses. In this case they are located in such a way that in the center of the panel a cross is formed. Harbison suggests that above and below this cross form there are “what appear to be stylized animal forms.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 16) In the images available, it is difficult to make out the details of either of the panels.

The West Face

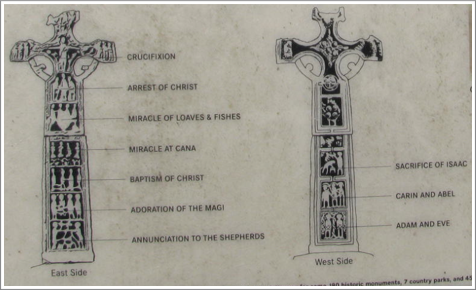

The entire west face of the cross, except for the band is dedicated to stories from the Gospels about Jesus. Beginning at the bottom and moving up we have the Adoration of the Magi, the miracle of the Wedding at Cana, the miracle of the Multiplication of Loaves and Fishes, the Triumphal Entry into Jerusalem, the Arrest of Jesus, and in the center of the head and on the arms, the Crucifixion.

The Shaft: The lowest of the images represents the story of the Adoration of the Magi. There are five figures in the panel. Sitting and holding the baby Jesus is Mary. Above her head are two bosses. At least one of the bosses may represent the star that guided the Magi. The Magi appear, two on Mary’s left and one on her right. They carry their gifts in their hands. Matthew 2:1-11 offers the text for this story. It is the only one of the four gospels that relates a visit by the Magi.

The image to the left is taken from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, figure 37.

The second panel up represents the story of the Miracle at the Wedding at Cana of Galilee. The text is found in the Gospel of John 2:1-11. Helen Roe suggests we read it as a story in two acts, the first across the top of the panel, the second across the bottom. (Roe, p. 83) Read this way Jesus appears in the center of the upper frame. He is flanked by Mary on the left and the master of the feast on the right. Here we see Mary requesting that Jesus do something about the lack of wine.

In the lower panel we have four figures, Jesus on the right faces three servants on the left. Along the very bottom of the frame are the six stone jars of water for the rite of purification. Jesus seems to hold a hand out and the servant nearest him may be taking water, now wine, from one of the jars at Jesus’ request.

In John this is recorded as Jesus’ first miracle. The text tells us this revealed Jesus’ glory. The story appears only in the Gospel of John.

Moving up the shaft we have the miracle of the Multiplication of Loaves and Fishes. All four gospels have a version of this story (see Matthew 14:13f , Mark 6:30f , Luke 9:10f and John 6:1f) . In Matthew the disciples declare that they have only five loaves and two fish. Mark and Luke follow a similar pattern. John is the only gospel to mention a young boy as the source of the loaves and fish.

The panel (below right) seems to reflect the story told in John. The figure in the center represents Jesus. He is flanked by two apostles, perhaps Philip and Andrew, the two apostles mentioned in the text in John. Below right and left are two figures who support a platter before Jesus that seems to hold the loaves and fish. Harbison points to the pellet like bosses along the bottom of the panel as the twelve baskets filled with leftovers at the end of the feast. (Harbison, 1992, p. 17 and Roe, p. 83)

The next scene is intended to represent Jesus’ Triumphal Entry into Jerusalem. This is another text that appears in all four gospels: Matthew 21:1f, Mark 11:1f, Luke 19:28f and John 12:12f. In Matthew and John the animal Jesus rides is referred to as a donkey. In Mark and Luke it is referred to as a colt. In the image to the right the animal appears to be a fine and full grown horse. Porter accounts for this incongruity by suggesting this is actually a scene from the life of Saint Columcille, founder of the monastery at Iona. (Porter, p. 41) Favoring this point of view is the presence on the south side of the cross of a scene identified as the Raven bringing bread to Saints Anthony and Paul, an image from the lives of the saints. (See above.) Against this point of view is the fact that all the other scenes on the face of the cross are connected to the life of Jesus.

The band: On the band at the top of the image to the right is a panel that includes a series of small bosses. The pattern is worn and indistinct.

The Head: The lowest scene on the head of the cross is a panel that extends below the ring. Above and below a figural scene are bosses. There are three below and a pattern of four above. In between we see the figure of Jesus flanked on each side by a soldier. Each appears to hold a club or sword against Jesus’ breast. The arrangement of the scene offers several possible interpretations, all related to the passion narrative. These include:

a) The Arrest of Jesus. This story appears in Matthew 26:47f, Mark 14:43f, Luke 22:47f and John 18:1f

b) The Mocking or Flagellation of Jesus. This episode is reported in Matthew 27:26f and Mark 15:15f, following Jesus’ condemnation by Pilate; in Luke 22:63f while Jesus is in the home of the High Priest and before he appears before the Council; and in John 19:1-5 before Pilate condemns Jesus.

c) The Ecce Homo. This refers to a statement made by Pilate as recorded in John 19:5 following the mocking and flogging of Jesus. In this version of the trial he is brought out draped in a purple robe and with the crown of thorns on his head.

Regardless of the interpretation, the image is a reminder of the events in the gospels that led to the crucifixion of Jesus.

The head of the cross is centered on the crucifixion. It is a classic image that contains Stephaton and Longinus on either side of the crucified Jesus and an angel on each shoulder. Stephaton on the right offers vinegar on a pole. Longinus on the left stabs Jesus near the armpit. In the constriction of each arm is a star shaped design with small bosses. On each arm are three figures. In each case a center figure is flanked on each side by what appears to be a soldier. The soldiers appear to beat the figure in the center. The most probable interpretation suggests these parallel scenes represent the thieves crucified with Jesus being beaten before being crucified.

Above the crucifixion image there appear to be another three figures. The image is worn to such a degree that no reasonable interpretation is possible from the art itself.

The North Side

The shaft: The photo to the left is from Harbison 1992, Vol. 2, figure 40. The panels are identified as the Baptism of Jesus (bottom) and Christ before the Doctors (above). There are alternative interpretations of the upper panel.

In the lower panel John the Baptist stands to the left. He is a towering figure and appears to hold a book in his hand. On the right is the much smaller figure of Jesus. The waters of the Jordan may be suggested at their feet. There is what probably was a dove above the head of Jesus. It is badly worn. The texts that describe Jesus’ baptism can be found in Matthew 3:13f and Mark 1:8f. The dove, as a symbol of the Holy Spirit, appears in both versions.

The most logical interpretation of the upper panel is that it represents Jesus before the Doctors. The text here is found in Luke 2:42f. In this interpretation a young Jesus sits or kneels in the presence of two larger figures who represent the teachers in the Temple in Jerusalem.

Biggers and Fennell offer a very different interpretation, suggesting the center figure is Moses. The only text that would come close to supporting this interpretation is found in Exodus 17:8f. The text, however, has Aaron and Hur holding up the arms of Moses. This image does not reflect this most important aspect of the text. (Bigger and Fennell p. 2)

The photo to the right is from Harbison 1992, Vol. 2, figure 40. The prevailing interpretation of the lower panel is the Slaughter of the Innocents. The upper panel has been interpreted as the Judgment of Solomon, the Slaughter of the Innocents, the Annunciation to the Shepherds and a scene from the legends of Cuchulain.

In the lower panel two figures, typically identified as soldiers wearing long robes, hold a smaller figure upside down. Each is holding a leg. The story of the Slaughter of the Innocents is found in Matthew 2:16f. Roe interprets the upper panel as an extension of this scene. She identifies the large figure as a soldier with a spear and the two small figures to the left as children who have been killed. (Roe, p. 84)

Bigger and Fennell, as with the upper panel above, offer an interpretation taken from the Hebrew Scriptures. This scene and the one above can be read together as reflecting the story of the Judgment of Solomon. This text is found in I Kings 3:16f. In the story two mothers argue over one child. The lower image could well reflect this scene. In this interpretation the upper panel represents Solomon ordering that the child be divided between the mothers. (Bigger and Fennell, p. 2) In their interpretation three of the four panels on the north side of the cross have themes taken from the Hebrew scriptures.

Roe and Bigger and Fennell group the upper two panels together as part of one story. They identify entirely different stories, however.

Harbison agrees with Roe and others in interpreting the lower panel to the right as representing the Slaughter of the Innocents. He sees the upper panel as representing the Annunciation to the Shepherds. He identifies the large figure on the right as that of an angel with a cross staff, the small figure lower left as a shepherd kneeling, and the small figure upper left as being that of another angel. (Harbison, 1992, p. 18)

Porter offers a non-biblical interpretation of the upper panel. He sees this image as a reference to the hero of Irish folklore Cuchulain. He identifies at least one of the figures on the left of the panel with a hound, an attribute of Cuchulain. (Porter, p. 15). This identification seems unlikely to me. The image is worn in such a way it is difficult to identify details that might assist with a more precise interpretation.

The band and above: The upper two panels on the north side of the cross are filled with decoration. This balances the north with the south side of the cross. On the band of the cross we have “S” spirals. On the panel above there are bosses from which Harbison sees animals emerging. (Harbison, 1992, p. 18)

The Iconographic Program of the Cross

The Arboe High Cross offers a consistent, logical and comprehensive set of images from both the Hebrew and Christian scriptures.

The shaft on both the east and south faces offer scenes from the Hebrew scriptures. In each case the lowest image reflects fallen humanity: Adam and Eve knowing their nakedness on the east and Cain killing his brother Abel on the south. On the east face the other images reflect the salvation of God for those in need: God provides a substitute sacrifice for Isaac, Daniel is saved from the lions and the three children are protected from the fiery furnace. In addition the scene of the sacrifice of Isaac prefigures the saving power of Jesus’ death on the cross. The central two images on the south are part of the David Cycle and also reflect the saving power of God: David rescues a lamb from a lion and David saves his people by slaying Goliath. The only variance from the Hebrew scriptures appears on the south side of the cross in the upper panel. This scene is taken from the lives of the Desert Fathers. It represents God’s provision for the faithful: the raven bringing bread for Anthony and Paul.

The shaft on both the west and north faces can be interpreted as outlining major events in the life of Jesus. On the west face we have the Adoration of the Magi, the miracles of Cana and the Loaves and Fish. On the north face we have, in this case moving from the top down to follow the chronology, the Annunciation to the Shepherds and or the Slaughter of the Innocents, Jesus before the Teachers and the Baptism of Jesus. These panels, taken together, and added to the images on the east and west faces of the head of the cross, offer images of the miracle of the birth of Jesus, his early life, the beginning of his ministry, his miracles, events from Passion Week and, depending on interpretation his Resurrection or Second Coming and Christ as Judge.

As noted directly above, the west face of the head of the cross offers images of some aspect of Jesus’ Arrest and Trial and a depiction of the Crucifixion. On the east face we have what may be an image of the Resurrection or Second Coming in a panel below an image of the Last Judgment.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 11, A 4. The Cross is marked on the map. The cross is located south of the B73. Just past the Moortown Post Office take the Ardboe Road south. It will turn to the southeast and lead to the cross site.

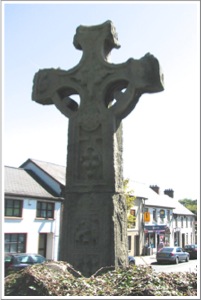

Caledon aka Glenarb

At one time there were at least seven crosses on a hill of Glenarb. The cross presently under consideration was once in the townland of Glenarb and was moved in about 1872 to the Caledon Demesne for preservation. The odd thing about the Glenarb hill site is that while it was clearly used for burial, there is no sign of any building having been there. Alexander Pringle writes that “Under its old name of Clonarb, or Cluain airbh, the place is mentioned in the Martyrology of Tamlacht, an Irish calendar of the ninth century, and also in the metrical calendar of Marian Gorman, which was compiled about the year 1167. Although no monastic buildings appear to have occupied the site it would seem to have been held in great veneration in early times, and may have been endowed with rights of sanctuary by the church, which would account fo the profusion of crosses, which were usually placed as boundary-marks to define the area of the city of refuge.” (Pringle, p. 292)

The cross at Caledon is a composite cross, composed of two parts. It is set up over Lady Jane’s Well in the grounds of Caledon Estate.

Shaft: The shaft stands 1.20m high. It tapers slightly from bottom to top and has a “box” at the top. “There is a circular device at the centre of the panel on each side.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 30) Only the device on the west is distinct. There is a central boss surrounded by eight circling and interlinked bosses.

Head: The head was part of another cross. It is imperforate and the arms, which seem to have been broken, presently extend just beyond the ring. The cross is framed by a round moulding. On the west face in the center is a large boss. There may have been a flatter boss on the east face, but only traces now remain.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 18, G 2. Caledon is located west of Armagh on the A 28. As noted above, the cross is on private property. Permission would be needed to view the cross. I have been unsuccessful in gaining permission to view this cross.

Clogher Crosses

The Site and Saint

While some traditions claim that the monastery at Clogher was founded by St. Patrick, the Register of Clogher states that Macartin was the first Bishop of the See. The Register lists Bishops or Abbots into the 16th century. (Ware, p. 30) This places the foundation of the monastery at about 490. In the early 5th century it appears that a new group of “political, cultural and ethnic kinsmen, again a mixed bag of Irish and British warriors” made an incursion into the area around Clogher. They came to be known as the Airgialla. (Warner, p. 41) It was the leaders of this group that St. Patrick would have encountered and among whom, and with whose support, Macartin established the Clogher monastery. This may not have happened as early as 490 as Eochu, the king of the area in the late 5th century was not a Christian. His son Caipre was a Christian as was his grandson Daimine. It is more probable that one of them encouraged and became patron of the monastery. It was built on Castle Hill adjacent to the royal site, probably in the early 6th century. (Warner, p. 45)

The church there was rebuilt in 1041 and dedicated to the memory of St. Macartin. At the Synod of Rathbreasail, in 1111, Clogher was recognized as an episcopal see. The church was rebuilt again in 1295 by Matthew M’Catasaid, Bishop of Clogher. The church and more than 30 other buildings burned to the ground in 1396.

Macartan’s hagiography states that he was born somewhere in Munster. Hearing of Patrick’s teaching he traveled to Armagh to hear him preach. He left behind a wife and child. He actually met Patrick first in County Leitrim. There he was baptized by Patrick and soon became Patrick’s “strong man”. It is said that when Patrick wore out Macartan supported him or carried him. Eventually, as he also grew older, he ask permission to settle down and live out his life in peace. The story goes that Patrick sent him to establish a monastery in Clogher. This tradition would support the rather later date for the foundation of Clogher monastery that Warner suggests above.

The Crosses

There are parts of five different crosses to the west of the Cathedral in Clogher. There are two composite crosses, each composed of separate shafts and heads. There is also a fragment of another cross on the ground between the two composite crosses.

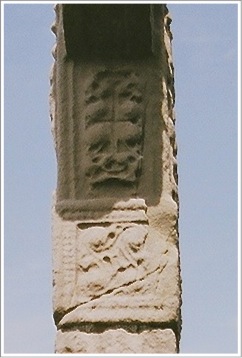

North Cross:

Base: The base of this cross is stepped near the top.

East Shaft: Near the top of the shaft there is a area of interlace forming four circular devices. See photo to the right.

East Head: The head of the cross is imperforate. In the photo above left the design on the head is clear. “At the centre of the head there is a four-point knot of interlace framed by four animals forming a cross pattern. Two of their heads are below, and the other two presumably on top, while the animals’ legs are presumably on the arms of the cross.” (Harbison, 1992, Vol. 1, pp. 42-43; Vol. 2, Fig. 118)

West Face:

West Shaft: There is a lozenge-shaped panel of interlace. See photo the the left.

West Head: At the center is a roundel of interlace.

North and South Sides: The sides of the cross are undecorated.

South Cross

Base: The base is undecorated.

East Shaft: The shaft is decorated with bosses of different sizes. See photo to the right.

East Head: The top of the head is broken and missing. The upper part of the shaft at the bottom of the head has bosses that may have animal heads related to them. The head is imperforate and in the center is a boss with interlace. Three sections of the ring also seem to have interlace design. The forth, the lower right, is unclear.

South Side Shaft: There is a panel of interlace.

North and South Side Head: The decoration on the ends of the arms is not clear. On the South there is a “three-point interlace in a bottom triangle, and there may conceivably have been upright animals in the vertical panels.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 43)

West Face Shaft: In the center of the shaft is interlace. See photo to the left.

West Face Head: The section of the shaft below the head has interlace. There is a boss at the center of the head with loose interlace. The ring has fretwork on the lower right and interlace on the lower left. The upper right may also have interlace.

Cross Fragment:

This fragment appears to be part of the shaft of another cross. It is undecorated.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 18, E 1. The crosses are located at St. Macartan’s Cathedral Church on the southwest side of Clogher. The Cathedral is located just to the southeast of the A 4.

The map is cropped from Google Maps.

Donaghmore

Very little is known about the monastery at Donaghmore. Some sources state that the monastery was founded by St. Patrick for St. Columb. Another source associates it with St. Patrick and St. Macerc. In each case the foundation was dated to the 6th century. The cross is a composite of two original crosses. The cross is typically dated to the 10th century. It has been in its present location since 1776.

The Cross

East Face: See photo to the left.

E 1: The Annunciation to the Shepherds.

E 2: The Adoration of the Magi.

E 3: The Baptism of Christ.

E 4: The Marriage Feast of Cana.

E 5: The Entry of Christ into Jerusalem. (?) Only a small fragment of the lower part of this panel survives. It is at the top of the lower section of the composite cross.

E 6: Unidentified Scene. Only a small portion of a panel survives. It is at the bottom of the upper section of the composite cross.

E 7: The Multiplication of the Loaves and Fishes.

E 8: The Mocking or Flagellation of Christ.

East Head:

Center: The Crucifixion

Top: Unidentified scene.

Arms: Thieves held by guards.

Ring: No decoration survives.

The image to the right appears on a sign posting at the site. Note there are some differences between the identifications of the scenes on the cross between those listed on the sign post and those identified by Harbison above. The primary difference is the identification of the panel just below the crucifixion as the Mocking or Flagellation of Christ (Harbison) and the Arrest of Christ (sign post).

South Side: The lower shaft, near the bottom of the cross, may have an image of Romulus and Remus (?). Above are a lozenge-shaped pattern, a rounded one and another lozenge-shaped image. On the upper section is a lozenge-shaped figure with interlace under the ring. Two triangles with knots of interlace are under the arm. The end of the arm shows an animal facing down, its front paws beside the head. (Harbison, 1992, p. 66) See photo to the right for lower section.

West Face:

Base: A horseman facing to the right. There may be other animals on the upper step of the base. See photo below. The lower portion of the shaft is hidden by the cemetery wall.

Shaft:

W 1: Adam and Eve knowing their nakedness.

W 2: Cain Slays Abel.

W 3: The Sacrifice of Isaac.

W 4: Unidentified scene.

W 5: “An upright lozenge-shape with somewhat rounded corners bearing four bosses in high relief, and possibly with animal-heads on top and bottom.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 66)

W 6: “A very curious rounded device having a raised circular boss bearing a sunken cross-shape in the centre and seeming to have small legs protruding from it. On the left there seems to be an animal-head in raised relief looking towards the left and two ‘legs’ extending beyond it above and below. The whole looks almost like a copy of a metalwork clasp.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 66)

West Head: An oblong figure from which four animal-heads seem to emerge.

West Arms: Bears seated upright with long necks.

Top: Broken away.

Ring: Interlace that may be animal interlace.

North Side: The design is similar to that on the south side. The animal at the base does not have any trace of figures beneath its body. Bosses in the roundel in the center are clearer. The animal at the end of the arm is less worn that on the south. See photo to the right.

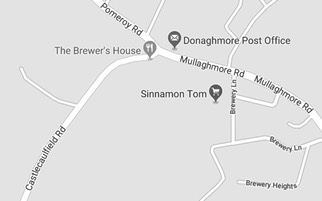

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 10, G 5. The cross is marked on the map but not in its exact location. The cross is located on the B43 across from The Brewer’s House, where the Castlecaulfield road goes to the south.

The map is cropped from Google Maps.

Errigal Keerogue

The site is also known as Errigal Kieran and it is said to have been founded or dedicated to St. Kieran. I presume this is Kieran of Clonmacnois. While local traditions reported in the late 19th century suggest that Kieran built the church there, the construction of the stone church would have been much later than the life-time of Kieran. (Simson, p. 29)

The site is also known as Errigal Kieran and it is said to have been founded or dedicated to St. Kieran. I presume this is Kieran of Clonmacnois. While local traditions reported in the late 19th century suggest that Kieran built the church there, the construction of the stone church would have been much later than the life-time of Kieran. (Simson, p. 29)

Simson writes: “In the graveyard surrounding the ruins of the church there stands an ancient stone cross. The ornamentation is partly defaced, in the centre of the cross on the far side is a kind of raised boss. It seems to have been ornamented but being greatly exposed to the weather it is almost completely worn away. There is no carving round the edges. . . The cross at Errigal stands about 5 ft. 6 in. high, and 2 ft. 6 in. in width.” (Simson, p. 30)

The photo above left shows the west face of the cross, the image to the right shows the east face. On the west there is a central boss in a frame created by incised lines. On the east face the outline of the cross and ring have been incised. The ring is imperforate.

Getting there: See the Road Atlas page 18, E 1. The location of the cross is marked on the Road Atlas. The site is located on the map to the right south of Seskilgreen near the left upper edge of the map.

Killoan

Nothing is known of the history of the site related to the Killoan cross-base. Foley, in an article on the history of County Tyrone writes: “Traces of many early church sites survive from the same period. Last remnants, such as a cross base at Killoan or an occasional bullaun, are sometimes clues to these earlier settlements. The large earthwork enclosures which once defended these sites are often sloughed out, but recent work on aerial photographs has turned up some new examples.” (Foley p. 89)

This decorated cross base (see photos left and right) is located “in a fence two fields down from a farm in Killoan townland.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 129) The Ordinance Survey has it marked as “The Head Stone”.

Only the south face is decorated. It has "a square panel consisting of four angular spirals divided by a square moulding and with a square in the centre, which gives it a cross form.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 129)

In conversation with the owner of the land and operator of a horse farm that is the “farm” mentioned above, I was told that the locals have long associated this monument with a head stone for an ancient grave. This explains the reason it is referred to as The Head Stone on the Ordinance Survey map. Harbison identifies it as a base for a cross, at least in part because it has a mortise in the top. It stands 90 cm high, is 58 cm wide and 32 cm thick. (Harbison, 1992, p. 129)

The land owner, who accompanied me to the site, stated that he is prohibited from plowing in that field and that it is his understanding that there was at one time a monastic workshop there.

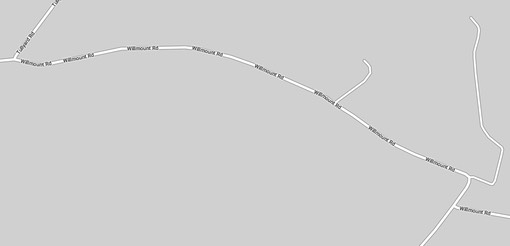

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 9, B 4. From the Langfield Primary School on the northwest side of Drumquin, take the Willmount Road west northwest till you come to the Tullyard Road, that goes to the north. South of this intersection is a Horse Stable. The cross is located in a field south of the stables that can be reached by a farm road. The field is down a steep hill and is on the left. On the map below, the location is on the extreme left center of the map.

The map is cropped from Google Maps.

\

Resources Cited

Allen, Kenneth, photo: http://www.geolocation.ws/v/W/File%3ASt%20Colman's%20Abbey,%20Ardboe%20-%20geograph.org.uk%20-%20300757.jpg/-/en

Annals of Ulster, CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts, http://www.ucc.ie/celt/publishd.html

Beagmore: http://www.megalithics.com/ireland/beagmore/beagmain.htm

Becker, Katharina; John O’Neill and Laura O’Flynn: Iron Age Ireland: Finding an Invisible people, Final Report to the Heritage Council, 2008 Archaeology Grant Scheme. https://www.ucd.ie/t4cms/iron_age_ireland_project_16365_pilotweb.pdf

Bigger, Franacis Joseph and Fennell William J., “Ardboe, Co. Tyrone: Its Cross and Churches”, Ulster Journal of Archaeology, Second Series, Vol. 4, No. 1 (Oct., 1897), pp. 1-7.

Colman of Arboe. parishofardboe.com. Parish History.

CopticChurch.net, 1998-2005, http://www.copticchurch.net/synaxarium/6_2.html

Coyle, Cathal, The Little Book of Tyrone, The History Press Ireland, 2018.

Dolan, Brian, “The Social the Technological Context of Iron Production in Iron Age and Early Medieval Ireland c. 600 BC - AD 900”, Vol. 1, https://www.academia.edu/1997896/The_Social_and_Technological_Context_of_Iron_Production_in_Iron_Age_and_Early_Medieval_Ireland_c_600_BC_AD_900_Volume_1_

Foley, Claire, “Tyrone”, Archaeology Ireland, Vol. 3, No. 3 (Autumn, 1989), pp. 86-90.

Harbison, Peter; The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and

Lacey, Brian, Cenel Conaill and the Donegal Kingdoms AD 500-800, in a chapter entitled “The ‘Ui Neill of the North’, Four Courts Press, 2006.

List of Monastic Houses, Tyrone, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_monastic_houses_in_Ireland#County_Tyrone

Mallabeny, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mallabeny

O’Kelly, M.J., “Bronze-Age Ireland.” in A New History of Ireland: Prehistoric and Early Ireland, edited by Daibhi O Croinin, Oxford University Press, 2005

O’Kelly, M.J., “Ireland before 3000 B.C.” in A New History of Ireland: Prehistoric and Early Ireland, edited by Daibhi O Croinin, Oxford University Press, 2005

O’Kelly, M.J., “Neolithic Ireland,” in A New History of Ireland: Prehistoric and Early Ireland, edited by Daibhi O Croinin, Oxford University Press, 2005

Parish of Ardstraw east, http://parishofardstraweast.com/StEugene.htm

Photographic Survey, Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

History of Parliament: (http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/member/stewart-william-1781-1850)

Jewish Virtual Library (http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Judaism/ark.html

Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae: omniumsanctorumhiberniae.blogspot.com See Saints of February, February 18,

Orant: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/430996/orant)

Porter, Arthur Kingsley, The Crosses and Culture of Ireland, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1931.

Pringle, Alexander, Morris, H. and Patterson O.D. and T.G.F., “Correspondence”, Ulster Journal of Archaeology, Third Series, Vol. 2 (1939), pp. 292-295.

Roe, Helen M., “Antiquities of the Archdiocese of Armagh: A Photographic Survey. Part III The High Crosses of East Tyrone”, Seanchas Ardmhacha: Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society, Vol. 2, No. 1, 1956, pp. 79-89.

Rootsweb, http://sites.rootsweb.com/~irlkik/ihm/ireclan2.htm

Simson, W. J., “Note on the Parish of Errigal Keerogue, Co. Tyrone”, The Journal of the Royal Historical and Archaeological Association of Ireland, Fourth Series, Vol. 7, No. 61 (Jan., 1885), pp. 29-30.

Ware, James, The Antiquities and History of Ireland, Dublin, 1705.

Warner, Richard B. “Clogher: an archaeological Window on Early Medieval

Tripartate Life

Tyrone and Mid Ulster” in Dillon, C. and Jefferies H. (eds), Tyrone: History and Society, Dublin, 2000. pp. 39-54.

Tyrone History: (http://www.rootsireland.ie/irish-world-family-history/tyrone-history/