What led to the creation and erection of the High Crosses of Ireland? What purposes did the crosses fulfill? What meaning did these monuments carry? What thoughts and feelings did they evoke in the late first and early second millennium? To attempt an answer to these questions requires some knowledge of the historical and cultural context at the time of the flowering of this form of artistic expression.

We might also ask a related question, what meaning, what thoughts and feelings do these crosses convey to the viewer in the early twenty-first century?

This article addresses the question of Purpose examining the use of the High Crosses for Commemorations, establishing Boundaries and Sacred Space, as sites for Prayer, Penance and Preaching, as signs of Status and Authority, and the Teaching function of a special class of the High Crosses, the Scripture Crosses. It also addresses the question of the Meaning of the crosses and The Meaning of the Crosses Today.

Purpose

Why were the crosses erected? A host of reasons have been offered. Some commemorated a person or event. Some set out limits for the monastery or special parts of the monastic site. It is almost certain that some, if not all, were used, at times, for preaching prayer, penance and sealing agreements. (Harbison, 1992, p. 352) The more elaborately carved crosses signified the wealth and authority of the monastery and its patrons. (Richardson and Scarry, p. 42) A special class of the crosses, the scripture crosses, also assisted in the teaching of scripture and reflection on scriptural truths. (Harbison, 1992, p. 353)

Commemorations:

Inscriptions on some of the crosses reveal dedications to individuals. The Kinnitty Cross in County Offaly offers one example. On the South face of the cross (see photo right) an inscription reads “A prayer for King Maelsechnaill son of Maelruanaid, A prayer for the king of Ireland.” On the north face another inscription reads “A prayer for Colman who made the cross for the king of Ireland, A prayer for the king of Ireland.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 356) Maelsechnaill was High King of Ireland at Tara from 846 to 862. Colman was likely the Abbot of this particular monastery during this time. (Photo, Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 97)

A second example comes on a fragment of a cross at Tuam in County Galway. An inscription on the South side of the cross has been read as “Prayer for the King, for Turdelbuch, descendant of Chonchobar. Prayer for the artisan, for Gillachrist, descendant of Tuathal.” On the north side there is another inscription (photo left) that reads “Prayer for the successor of Iarlath, for Aed O Ossin, who had the cross made.” (Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 617) This is one of only a very few crosses where we know the name of the carver, Gillachrist O’Toole. The Turlogh O’Connor and Aedh O Ossin mentioned were respectively a king and a bishop. O Ossin , who appears to have been bishop when the cross was made, became a bishop in 1126 and archbishop in 1152. Turlogh died in 1156. The cross must, therefore, have been carved between 1126 and 1152, while both men were still alive and O Ossin was still a bishop.

Boundaries and Sacred Space:

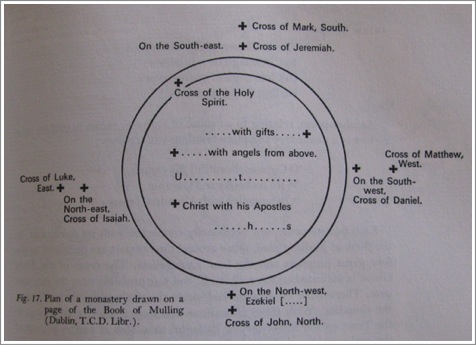

Crosses often marked out the boundaries of the monastic site and within the monastery proper marked the most sacred areas of the precinct. The Book of Mulling (Moling) is a late 8th century pocket Gospel. The text includes a plan of the monastery St. Moling founded in County Carlow, at what is now St. Mullins. That diagram is seen below. (Henry, 1965, p. 135)

The diagram shows us twelve crosses. Eight of these crosses are outside the outer wall of the monastic enclosure. Four of these are named for the Gospel writers and four for prophets of the Hebrew scriptures. Two of the four inside the enclosure are named: the Holy Spirit cross, which may have stood on the wall; and Christ with His Apostles. In this example the eight crosses outside the enclosure are located at the cardinal points and were likely intended to mark out the area of the monastery. In addition all of the twelve crosses served an apotropaic or protective purpose. They were understood as warding off evil and offering God’s protection and care.

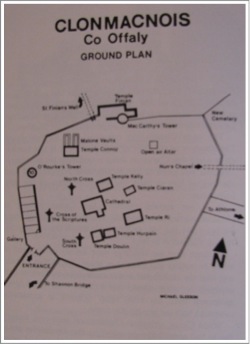

In some instances it is possible to speculate that certain crosses marked out the most holy areas of the monastery. One example is Clonmacnois in County Offaly.

The image to the left is found in Clonmacnois by Kenneth MacGowan,( p. 6). It shows the main walled enclosure of the monastery in its present state. Three crosses are noted on the diagram. They are the South Cross, thought to date from the 8th century. The North Cross, with a suggested 9th century date, and the Cross of the Scriptures, dated to the early 10th century. (MacGowan, p. 36)

These crosses form a kind of arc around the west side of the Cathedral. The Cathedral was built of wood in 909 under the patronage of King Flann, High King of Ireland, and Bishop Colman, Abbot of Clonmacnois and Clonard. (MacGowan, p.16) Its construction and the carving of the Cross of the Scriptures were at least near the same time. It is possible to infer from the present placement of these three crosses that they may have been intended to mark out the most holy part of the monastic enclosure, the Cathedral.

A further example of crosses marking the boundaries of monasteries comes from Kilfenora in County Clare. “Seven stone crosses are associated with Kilfenora. Six crosses survive. The positioning of these would appear to outline the boundary of the original monastic enclosure which indicates a diameter of not less than 300m.” (Kilfenora Timeline) Five of the surviving crosses have been moved into the protection of the old church.

Prayer, Penance and Preaching:

From at least the seventh century in the west, the cross was an object of veneration. This quasi-sacramental function of the cross started with the Church in Jerusalem after Saint Helen, mother of the emperor Constantine, while on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 326, claimed to have discovered part of the Holy Cross. Veneration of this fragment took place each year on Good Friday. This veneration came to be applied to all crosses. (Catholic News Agency) In 825 the Council of Paris specifically approved of the veneration of the cross and explained the meaning of this. The cross to the left is the Errigal Keerogue Cross in County Tyrone.

“Therefore, the adorers of images are wont to oppose the veneration, adoration or exaltation of the Holy Cross in defense of their position why it is not allowed to adore images in the same way as crosses. To whom we must reply that Christ chose to be hung not on an image but on a cross, when he wished to redeem the human race, and therefore Holy Mother Church throughout the whole world, among other innumerable sacraments of the cross which have been enumerated in multiple ways far and wide throughout the whole world by the holy fathers, has decreed that it is permitted to all Catholics because of the love of the Passion of Christ alone that wherever they should see crosses they may venerate them if they wish by bowing, and in addition on the holy day on which the Passion of the Lord is specially venerated throughout the whole world, that the whole priestly order or the whole people should with all devotion prostrate themselves in adoration.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 353)

In this sense we can easily visualize the crosses being places for individual and corporate prayer. Given the generally small churches of the time, it is also easy to imagine corporate worship being held with a cross as the backdrop.

Status and Authority:

Richardson and Scarry state “it is hard to avoid the impression that ornate stone crosses, intricately carved and painted, were used by ambitious kings and monastic rulers as a way of proclaiming their own status and authority.” (Richardson & Scarry p. 42)

Evidence from the inscriptions (see above) suggest the important role of some crosses in commemorating important kings and abbots. In some cases, as at Tuam, the crosses were erected and dedicated during the life of those honored.

Evidence from the inscriptions (see above) suggest the important role of some crosses in commemorating important kings and abbots. In some cases, as at Tuam, the crosses were erected and dedicated during the life of those honored.

The expense involved in the carving of the High Crosses, especially the more elaborately carved ones, reflected the wealth of the monastery and its patron(s). Having one or more of these crosses visibly proclaimed the wealth of the monastery.

In at least one case, we have clear evidence that a group of crosses were commissioned and carved with the express purpose of gaining ecclesiastic position for the church and community. The monastery/church was Kilfenora in County Clare. According to the history of the church prepared by the community in 2013, Kilfenora lost its status as a Bishopric at the Synod of Rathbreasail in 1111. In 1152 at the Synod of Kells an effort was renewed to recover their former status. “In a show of unity, renovation of the cathedral and the carving of High Crosses began. Such was their determination that Kilfenora succeeded in retaining its standing and was listed as one of the thirteen Dioceses in the province of Cashel.” (Kilfenora Timeline) The cross pictured to the right is the Doorty Cross at Kilfenora.

The Teaching function of the Scripture Crosses:

Harbison states that “All these purposes (and others) could have been, and doubtless were, served by wooden or plain stone crosses, but the figure-carved crosses must also have conveyed certain messages to the viewer” (Harbison, 1992, p. 325) This observation relates, especially, to what are known as “Scripture Crosses”. These crosses contain images from scripture, and, in some cases, the lives of the Desert Fathers.

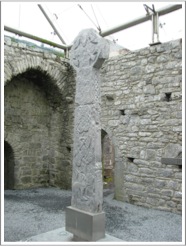

There are many excellent examples of figure-carved crosses that contain numerous biblical images. The Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois in County Offaly (photo left), the Cross of Muiredach at Monasterboice in County Louth and the Arboe High Cross in County Tyrone all illustrate this type of cross.

The use of such images was, for a time, controversial. During the Iconoclastic Controversy of the 8th and 9th centuries the use of images was discouraged. This was the situation during the reign of Charlemagne in the west. Charlemagne was King of the Franks from 768 and later, from 800, the first emperor in the west since the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The Synod of Frankfurt in 794 rejected the adoration of images and it is probable that the decoration of churches with images was at least officially discouraged during the rest of Charlemagne’s reign.

Louis the Pious, son of Charlemagne was emperor from 814. In 825 the Council of Paris while preferring the cross over pictures, recognized the educational and religious value of pictures, so long as they did not become objects of adoration. Following this Council, Louis personally promoted the painting of frescos illustrating scenes from scripture such as those on the walls of his chapel at Ingelheim. (Harbison, 1992, p. 314)

With this background it is clear that the scripture crosses served a purpose of aiding in the teaching of scripture. In this way they parallel the use of frescos in some of the basilica-type churches on the Continent. Irish churches, in general, had neither the wall space to paint such frescos nor the interior light for them to be seen. Hence, the same purpose was achieved by the development of the high crosses and their prototypes. (Harbison, 1992, p. 353)

While agreeing with Harbison that the scripture crosses served an educational purpose, Stalley states “It has often been suggested that the scripture crosses were designed for teaching, with the Christian truths being expounded to lay folk gathered around. This is perhaps too romantic a view, as the scenes are not always easy to see and comprehend. They appear better suited to an educated monastic audience than to the local populace. (Stalley, p. 42)

The scripture crosses did more than serve as teaching aids. The images on the crosses provided opportunities for devotional reflection on the great truths of scripture. They provided encouragement, hope, faith and love in the midst of the joys and sadness, the successes and defeats, the hopes and fears of daily living. The photo to the right illustrates the Last Judgment on the Cross of the Scriptures at Clonmacnois in County Offaly. More on the meaning of the images on the crosses in the next section below.

Meaning and the High Crosses:

When we ask the question of meaning, what are we asking? We might be asking about the various symbols and designs used in the work of art. Is there a religious message in the symbols that we can understand? Or we may be asking “what thoughts the [art] aroused in the mind” of a contemporary with its creation? (Bagley, p. 8) In what follows we will attempt to do a bit of each. In either case it is important to ask questions about the historical context in which the crosses were created.

Cultural Background:

Robin Flower described a part of the spiritual ethos of the Irish monasteries during the 8th and 9th centuries. During this period there was a revival of the acetic spirit that connects Irish and Egyptian monasticism. This was reflected in the development of the Irish Penitentials and the Stowe Missal, a mass-book written at Tallaght in the early 9th century. Saints Paul and Anthony of the desert were important figures as setting an example of the monastic life. They appear on some of the figure-decorated scripture crosses. (Flower, p. 89)

These monks lived in a world that was populated by spirits, both good and bad. The monks had a sense of being in constant communion with the saints and in conflict with evil. Ancient martyrs and hermits, who had suffered and overcome evil in the fight seemed to be very present to them. As a result, prayers of supplication were continually made to “Christ’s passion and the merits of his saints to help them in their desperate battle.” (Flower, p. 91)

Prayers that survive from this period are reflective of a type called the commendation animas. These were prayers of the Roman Breviary. One of these prayers is the Epilogue to the Festology of Oengus, written by Oengus between 797 and 808 at Tallaght. (Flower, p. 92) Onegus (also spelled Aengus) was a monk at Tamhlacht or Tallaght and was surnamed Cele De (servant of God). The Epilogue is a long litany that seeks the help of Christ and his saints, these petitions are reflected on the scripture crosses by figures from both the Hebrew and Christian scriptures. Flower states that “our Irish poems are clearly variations on this prayer, detached from the immediate purpose of the commendatio animas and used as a general apotropaic formula against all evil.” (Flower, p. 92)

In the fragment of the Epilogue quoted by Flower, there are several references to heroic figures from the Hebrew scriptures. For example:

“Save me as Thou didst save Isaac from his father’s hands.

Save me as Thou didst save David from Goliath’s sword.

Save me as Thou didst save Daniel out of the lions’ den.

Save me as Thou didst save the Three Children de camino ignis.”

Each of these scenes appear on some of the scripture crosses of Ireland. This is illustrated in the following four images. The image above left is from the Arboe Cross in County Tyrone. It represents Abraham and the Sacrifice of Isaac. The next image to the right (top image) illustrates David slaying Goliath, also from the Arboe Cross. The third image, below on the left, illustrates Daniel in the Lion’s Den on the North Cross at Castledermot in County Kildare. The last of the four images below right shows the Three Children in the Fiery Furnace from the Tall Cross at Monasterboice in County Louth.

In addition, some of the saints of Ireland are mentioned in the prayer.

“Save me as Thou didst save Patrick from poison at Tara.

Save me as Thou didst save Kevin from the falling of the mountain.” (Flower, pp. 91-92)

A second prayer of this type, the hymn of St. Colman Moccu Chluasaig, “is prefaced by a prose introduction which suggests that it was used as an amulet against plague and as a charm to be used upon journeys.” (Flower, p. 93) Based on this, Flower asserts “the prayer was, then, at once a liturgical formula, a private devotion and a charm.” (Flower, p. 93)

Flower then suggests that the figural scenes on many of the scripture crosses reflect the written and oral prayers of the people, both religious and laity. “So conceived, the crosses may well have seemed to possess, like the prayers, a magical efficacy. And we have evidence that in certain cases the crosses served for sanctuary. So that it may be said of one of these high crosses, as Oengus said of his Martyrology, itself a vast repository of the merits of the saints stored up to the same end, that it was a city of refuge, a strong rampart against men and devils, a vehement prayer towards God, a psalm that declares great might.” (Flower, p. 95)

As we have seen above, the cross had become an object of veneration that was affirmed as such by the Council of Paris in 825. The crosses placed in and around monasteries, in market centers and in the countryside carried the full meaning of the Passion of Christ and served as a source of protection and an object of devotion. This was true regardless of how simple or ornate the cross might be, as illustrated by the photos of crosses above in this section.

Robert Bagley considers the decoration of the crosses to be a reflection of the “surpassing importance” of the cross as a symbol. He suggests that those who planned and carved the crosses may have added decoration to “convey that importance by making the cross spectacular.” (Bagley, p. 13) This, he suggests, may have been a more important function than the “conveyance of symbolic meaning.” (Bagley, p. 18) This may be especially true for the crosses that are adorned primarily with geometric design (see the Geometric Design page on this website).

The Meaning of Geometric and Figural Images:

The idea that decoration adds a value to the crosses that surpasses any notion of the symbolic meaning of individual symbols or decorative patterns used, does not keep the human mind from asking what was in the mind of the planners and carvers of these stone monuments as they added spirals, stars, interlace, fret work and zoomorphic design to their plans. In the Geometric Design page on this website there is a section titled “The Meaning of Interlaced Patterns” that addresses this question in part.

The use of figural art, especially on the scripture crosses, serves more than a decorative purpose. The biblical scenes tie together the beauty of decoration that makes the crosses spectacular with a communication in story of the acts of God in salvation history.

Francoise Henry discusses this in her book Irish High Crosses. The high crosses contain a set of familiar biblical scenes, represented in a manner that was probably borrowed from the continent. “In most cases they are not chosen as realistic representations of an event, but essentially for their inner significance, either as manifestations of God’s help to the faithful or as ‘types’ or ‘prefigurations’ of an event in the life of Christ.” (Henry, 1964, p. 35)

Henry offers an example of the multiplicity of meanings that can reside in one scene. “So this one scene — the sacrifice of Isaac by his father Abraham — can appear as having at least three different interpretations: either Isaac can represent the faithful saved from death by God, or he can be a prefigure of Christ carrying his cross, or his sacrifice by Abraham can be a prototype of that of Christ, and consequently of the sacrifice of the mass.” (Henry, 1964, p. 38) The meaning may be altered by the arrangement of the other scenes around it.

There is a tendency on some of the crosses to bring the scenes from scripture into a historical sequence. This can be seen on the Arboe High Cross in County Tyrone. On the east face, moving from the bottom of the shaft upward we have Adam and Eve, the Sacrifice of Isaac, Daniel in the Lion’s Den, and the Three Children in the fiery furnace. On the west face, again moving upward we have the Adoration of the Magi, the Wedding at Cana, the Loaves and Fishes, Jesus entry into Jerusalem, the arrest or mocking of Jesus on the arms of the cross and the Crucifixion in the center of the head. Henry suggests that this mirrors a melding of symbolism and history on the Continent. (Henry, 1964, p. 45)

So the crosses served as a reminder of the importance of the Crucifixion and Resurrection of Christ for the faith. They pointed to the merits of the saints, they offered a refuge against evil. In addition, the scripture crosses also reflected the written and oral prayers of the time. The crosses offered encouragement, hope and faith in the face of the challenges of daily living.

The Meaning of the Irish High Crosses Today:

Speaking personally, when I view the Irish High Crosses, I see them through eyes of faith. Like those who planned and carved these iconic works in stone, I view them as a Christian. The cross is an important symbol of my faith. It reminds me of the love of the Creator as revealed through the life and ministry, the death and resurrection of Jesus. It holds the promise of God’s care, presence and assistance in difficult times in life. It lifts my heart in thanksgiving and praise in every experience. At the same time, the cross challenges me to live my life as a worthy response to the love I have experienced through the Creator, the Christ, the Holy Spirit and the community of faith.

These thoughts and feelings lie beneath the surface as each cross I find comes into view. My immediate response takes in the majesty of the appearance of the cross. A couple of examples might help to convey this sense of majesty and the variety of thoughts and feelings the crosses evoke in me.

The cross pictured above is the Reenconnell Cross in County Kerry on the Dingle Peninsula. It is a roughly carved cross and has no decoration except for an inscribed cross with a ring around it on the head of the cross. This cross has a pleasing shape with the upper and lower shaft close to equal in length and the arms also relatively balanced in length. The cross stands in a field, the second field over from an unlabeled gravel road. Peter Harbison suggests it may have been an old pilgrimage site. The splendid isolation of this cross in a beautiful setting of rolling hills and tilled fields reminds me of the solitary lives lived by some of the early hermits and small communities of monks. It reminds me of the devotion of those whose faith led them away from home on pilgrimage. These pilgrims remind us that we too are on a journey and are connected to all who see life as a journey of faith in communion with the Holy.

The second example is quite different from the first. The Patrick and Columba Cross is located in the city of Kells in County Meath. It is located within the ancient walls of a major monastic establishment that is adorned by two other decorated crosses and a decorated base. This is an elaborately carved scripture cross. In its present form it is missing the cap, but this does not detract from its impressive appearance. In contrast to the cross at Reenconnell, the Patrick and Columba Cross is covered with decoration and figural design.

The Patrick and Columba Cross serves as a reminder of some of the key stories in both the Hebrew and Christian scriptures that tell of the healing, and empowering love of God. Here I can imagine myself or others spending time learning and reflecting on the message and meanng of these biblical texts, or becoming lost in reflection on panels of interlace and inhabited vine-scroll. The decorative elements such as interlace also serve as a reminder of our connection with the pre-Christian Celtic tradition as it developed in Ireland, and of the interconectedness of all life. The ring on many of the crosses reminds us of that connection as it may refer back to the importance of the sun in the indigenous religion of the Celts.

The crosses inside monastic enclosures, like the Patrick and Columba Cross above stimulate reflection on worship practices dating back to the pre Christian period and continued into the Christian era. One tradition was Sunwise Walking or deasil. The practice was to walk sunwise or clockwise three times around something to be blessed or healed or consecrated. Worshippers may well have walked around a high cross near the entrance to the sanctuary three times before entering for worship.

With crosses like that of Patrick and Columba I stand in amazement at the quality and beauty of the planning and carving of these crosses. They reflect a faith that seeks to give ones best to honor and praise God. They are a reflection of extravagant gifts of time, talent and financial resources that express the the depth of their faith.

These crosses, as mentioned above, were objects of veneration, prayer, penance, preaching, meditation and reflection on the spiritual truths of scripture. It is possible to feel the prayers of generations of Christians infused in the crosses and sites. Here monks, priests and laity, pilgrims and locals have prayed. And so these prayers inhabit the crosses, the ruins of churches and round towers that in some cases surround them. The crosses continue to mark out sacred space.

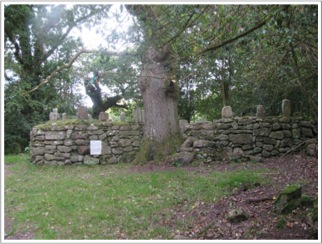

Some crosses and cross fragments have been preserved in a way that lifts up the importance to the human spirit of collecting and preserving sacred objects, especially in sacred places. In the Glen of Aherlow in County Tipperary, there is a small circular enclosure known as St. Berrihert’s Kyle. The heads of two imperforate crosses are built into the east wall of this enclosure. The photo below left is a view of this enclosure from the west. The photo to the right below shows the two cross heads, some of the other crosses and cross inscribed stones collected here and some of the votive offerings left by those who come here for prayer. This is a small and remote site that oozes spiritual power and human devotion. It feeds the spirit.

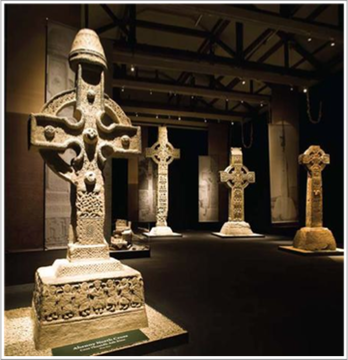

An entirely different experience of the High Crosses was on display in 2011-2012 at the National Museum of Decorative Arts and History located in the Collins Barracks in Dublin. As illustrated by the photo to the right this was a dramatic exhibit of plaster casts of five of the most impressive of the Irish High Crosses. (Source of photo:http://www.museum.ie/en/exhibition/list/displaying-high-cross-reproductions.aspx)

The four crosses shown in this photo are (from left to right) Ahenny North Cross (County Tipperary), Monasterboice Tall Cross (County Louth), Monasterboice Muiredach’s Cross (County Louth) and Drumcliffe Cross (County Sligo).

These casts were first exhibited at the 1853 Irish Industrial Exhibition in Dublin. This tasteful display emphasized the sacredness, power, and awe these crosses can inspire. They also point to the sharpness and drama of the carvings, some of which has been lost from the original crosses during the 160 plus years since they were cast.

We each bring our own experience to our interaction with the Irish High Crosses. Perhaps a small taste of the uniqueness, beauty and inspirational quality of the crosses can be conveyed even by the photos and commentary of this website. I hope so.