The location of County Waterford is indicated by a red star on the map to the left.

There are two crosses, or more properly a cross-head and a cross base related to County Waterford. The cross base Ballynaguilkee Lower aka Ballynamult is LOST. The cross-head is at Lismore. Prior to addressing these important monuments, a brief overview of the history of the present County Waterford, up to about 1200 CE, is appropriate.

History of County Waterford

During the historic period Waterford has been a part of the Province of Munster. However, the history of human habitation began in the megalithic period, perhaps as early as 8000 BCE.

Mesolithic Waterford: 8000 to 4000 BCE

An article in the Irish Times, published in August of 2018, reported that surveys “carried out on items found at Creadan Head, near Dunmore East, Co Waterford” may stretch back to 8000 BCE. The finds included flint tools. The study concluded that “Every indication then was that people did come to Waterford as early, if not earlier than, people came to the north and west of Ireland. This understanding changes Irish prehistory, and this proposed project aims to verify this.” (Dalton)

Neolithic Waterford: 4000 to 2500 BCE

The Neolithic age in Ireland saw the arrival of agriculture, the management of domesticated animals, pottery and weaving. Megalithic monuments of various types were constructed during this time.

The Neolithic people of County Waterford constructed Passage Tombs. For example the Matthewstown Passage Tomb is said to date to 2500-2000 BCE. It is located about one mile north of Fenor. It is one of a group of passage tombs in County Waterford that have been named among the Scilly-Tramore group. This means they have similarities with tombs in Cornwall and the Scilly Isles. This suggests that the builders may have come to Ireland from Cornwall. The tomb “is 4.5 m (fifteen feet) long and about 1.8 m (six feet) wide. There are two rows of five orthostats protruding above the ground to about 1 metre (three-and-a-half feet). This grave was covered by four large stone slabs.” (Matthewstown)

In addition to the Passage Tomb at Matthewstown, County Waterford has Court tombs such as the one at Ballynomona Lower; Portal tombs, such as Ballyquin (pictured above); and other Passage Tombs like the one at Harristown. (Irish Megaliths)

Bronze Age Waterford: 2500 to 500 BCE

Metallurgy arrived in Ireland with the Beaker people, who may have come to Ireland initially in search of copper and tin ore. The combination of these two ores created bronze. The advent of the Bronze Age brought a revolution in technology, tools and weapons.

In an article titled “A Bronze Age settlement and ritual centre in the Monavullagh Mountains, County Waterford, Ireland,” Michael J. Moore discusses “A complex of settlement and ritual monuments . . . covering a core area of c. 4km squared. There are “three cemeteries or sanctuaries.” (Moore)

Another Bronze Age complex can be found in the valley of the Nire River in the Tooreen towns land. At this site “There is evidence of several Fulacht Fia, ancient field systems and settlements, a stone circle, a stone row and a pair of Bronze Age Barrows, one of which contains evidence of a cist burial.” The article on Tooreen continues “There are no less than two Barrows in Tooreen East. They are considered to be Ring Barrows, one of which contains evidence of a Cist Burial. (These are single grave cists and became the burial of choice towards the end of the Bronze Age.)” (Tooreen)

Iron Age Waterford: 500 BCE to 400 CE

There is some evidence that iron working arrived in Ireland prior to 500 BCE, perhaps as early as 811 BCE. This is based on carbon-dating of an iron spearhead found in the River Inny in County Westmeath. (Iron Spearhead) Traditionally, the Iron Age is said to have begun in Ireland with the arrival of the Celts, around 500 BCE. This find suggests the technology may have arrived earlier. In addition to another leap forward in technology that effected agriculture and warfare, it was during the Iron Age that promontory forts and ring forts were constructed.

Coastal Promontory Forts seem to date to the Iron Age. Those in Waterford are similar to those in Britain and Brittany. For example, “Near the village of Annestown, the site of the Promontory Fort at Woodstown juts out southwards into the Celtic sea. The Fort was originally cut off from the landward side by a bank measuring 7 metres wide and 2.2 meters high and a Fosse (Moat) of 1.6 meters in width. The entrance was towards the East end. The internal area of the Fort was approximately 1,100 square metres. However, this may have been greater and have once included Brown's Island which is now separated by the sea.” (Woodstown)

During the second half of the Iron Age the Roman Empire was active in Britain. At Stoneyford in County Kilkenny archaeology has indicated the presence of a small Roman colony in Ireland. The site was probably reached from the Waterford harbor via the River Nore. Speculation is that these Romans were “traders, refugees or even shipwrecked sailors.” (O Croinin, p. 175)

Late Iron Age and Early Medieval Waterford

As early as 278 CE, the primary tribal group in the area of present day County Waterford were the Desii. Tradition tells us that in the third century the Desii held territory in Meath. As the story goes, in 278, Aengus, prince of the Desii, rebelled against King Cormac, king at Tara. The Desii were ultimately defeated and driven south into Munster. The story suggests that the Desii were granted land in what is now County Waterford. (Waterford Museum) The Desii seem to have had a connection with south Wales, Cornwall and Devon. (History of Ireland in Maps, circa 400) The Desii are remembered currently in County Waterford as the area around Dungarvan is still known as the Desies. At some point in time, by 600 at the latest the Desii were referred to as the Desi Muman.

Discoveries at the Woodstown archaeological site in County Waterford there is evidence that the site may have been a settlement of the Desii in the fifth century, during the time of St. Patrick. (Woodstown wiki) However, Patrick is not given credit for converting the Desii. They were converted to Christianity by St. Declan and their conversion pre-dated Patrick by about 30 years. (Fenor) The site at Woodstown was later taken over by Vikings.

By at least 700, the Eoganachta ruled Munster. This suggests that the Desii Muman were vassals of the Eoganachta. It has been reported that the tribute of the Prince of the Decii to the King of Cashel included: “2,000 chosen hogs; 1,000 cows; and in war, 1,000 oxen; 1,000 sheep; 1,000 cloaks; 1,000 milch cows yearly.” (Waterford Museum the Decies)

Viking Age and Anglo-Norman Waterford

The Woodstown archaeological site was mentioned above. It is located on the south bank of the River Suir, about 5.5 km west of Waterford City. This site became a Viking longphort. It was a defensive site intended to protect Viking ships and raiders and their plunder. “About 4,000 objects including silver ingots, lead weights, ships nails, Byzantine coins and Viking weaponry have been recovered.” These objects date to the mid to late ninth century. In addition, “600 features such as house gullies, pits and fireplaces” have been found. This suggests a “densely populated and affluent settlement.” (Woodstown wiki)

Underlining the importance of Viking presence in the Waterford area is the fact that they established what is now Waterford City inn 914. “‘Waterford’ is one of the few Scandinavian place-names in Ireland and appears to be derived from the Old Norse words for ‘ram fjord’ or ‘windy fjord.’” (O Croinin, p. 819) The site was “Probably chosen for the access it gave to the hinterland of the rivers Nore, Suir, and Barrow.” (O Croinin, p. 839)

By the early eleventh century the O’Faolains and the O’Brics were the principal families of the Desii tribe. At Clontarf in 1014, Mothla, son of Faolan, chief of the Desii, fought with Brian Boru against the Danes.

From at least the early eleventh century the two families were in conflict. For example, “In 1031 Murray, the son of Bric slew Diarmid, son of Donal O'Faolan at the battle of Sliabhgua, in the County of Waterford.” (Waterford Museum the Decies)

Norman Waterford

It was a leader of the O’Faolain family, Malachi O’Fallon, who defended Waterford against Strongbow in Ireland in 1170. Strongbow with at least 200 knights and 1000 soldiers joined with a force lead by Raymond and laid siege to Waterford. The walls were eventually breached and at least 700 defenders died.

Norman Invasion

In 1177, King Henry II of England granted the City of Waterford, and in essence what is now County Waterford, to Robert le Phuer (le Poer). This family succeeded the Desii in ruling the territory.

This brings us to the close of the twelfth century and the end of the era of the High Crosses of Ireland.

Ecclesiastical History

Christianity arrived in Ireland, and in what is now County Waterford, before the arrival of St. Patrick in Ireland. As noted above, the Desii were converted to Christianity by St. Declan in the early fifth century. There is a tradition in Munster that four or five saints introduced Christianity to the province before St Patrick arrived. Depending on the list these were: St Ailbe of Emly, St Ciaran of Saigir, St Abban of Moyarny, St Declan of Ardmore and Saint Ibar, uncle to St. Abban. In addition, it has often be noted that Palladius was sent to Ireland before Patrick. His work was largely in the south and even in 431, he was sent to the Christians in Ireland.

As will be noted in the list of early monasteries in County Waterford below, there are no claims that St. Patrick founded any of them. Only two, Ardmore and Kilmacleague were founded in the fifth century. (Monastic Houses of Waterford)

The monastery at Lismore is the only one of these monasteries that definitely produced a High Cross. The head of the cross is still in possession of the Lismore Church of Ireland Cathedral. A cross-base, now lost, that will be discussed below may have been associated with one of these monasteries, but if so, we have no way of knowing which.

Achad-Crimthain,early site, founded pre 829, possibly in Waterford

Achad-dagain,early site, founded pre 639

Ardmore,early site, founded 5th century by St. Declan

Cathair-mac-conchaid, early site, founded by 7th century

Clashmore,early site, founded pre 646-56 by Cuancheir

Disert-niabre,early site, founded by St. Medoc of Ferns

Dungarvan,early site, founded 7th century by St. Garvan

Killbunny,early site

Kilmacleague,early site, founded 5th century by St. Mac Liag

Kilmolash,early site, founded by St. Molaise (of Leighlin?)

Lismore, early site, founded 636 by St. Carthach (Mo-chuda)

Lismore,early site, nuns, founded 7th century

Little Island,early site, possibly in Co. Wexford

Molana,early site, founded 6th century by St. Molanfide

Mothel,early site, founded 6th century by St. Brogan

The Vikings who settled in places like Dublin and Waterford were pagans when they arrived. By the late tenth century they were mostly Christians. “We find . . that Viking chiefs were giving their sons the names of Christian saints, such as Gilla Patraic, son of Ivar of Waterford.” (O Croinin, p. 645)

In the late eleventh century (1096) A bishop for Waterford was consecrated. Anselm, archbishop of Canterbury was asked to consecrate Meal Isu (Malchus) Ua hAinmire as bishop for the Hiberno-Norse of Waterford. He agreed. There was a connection between Anselm and Malchus. Both had trained at St. Albans and Malchus had served as a priest under bishop Walkelin of Winchester. This placed the diocese of Waterford under the control of Canterbury. (O Croinin, p. 911)

In 1111, at the Synod of Rath Breasail, the churches of Ireland were brought into conformity with the Roman system of organization. The monastic structure of the church was replaced with the diocesan and parish-based system. At this time the diocese of Waterford came under the authority of the Archbishop of Cashel.

The High Crosses of County Waterford

As stated above, there are two crosses, or more properly a cross-head and a cross base in County Waterford. The cross base Ballynaguilkee Lower aka Ballynamult is LOST. The cross-head is at Lismore.

Ballynaguilkee Lower aka Ballynamult

While nothing is known of the site for which this cross-base is named, it lies in an area known as the Sliabh gCua, a district in West County Waterford that lies between Clonmel and Dungarvan between the Comeragh Mountains on the east and the Knockmealdown Mountains on the west.

The Historic Environment Viewer identifies a Church at Ballynaguilkee Lower that is described as follows: "Situated in pasture on level ground at the top of an E-facing slope down to the N-S Finisk River, c. 300m to the SE. This is an early ecclesiastical site with traces of an oval enclosure (dims. 63m N-S; 46m E-W) visible as a scarp N-S and a slight dip S-W. The perimeter is incorporated into a field bank W-N. The base of a stone cross (dims. c. 0.35m x 0.25m.” (Historic Environment Viewer)

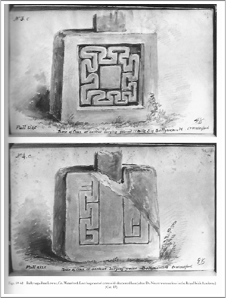

The illustration to the left was produced by George Victor Du Noyer an Irish painter, geologist and antiquary. From 1834 until 1848 he was employed by the Irish Ordnance Survey. This watercolor would have been produced during that time.

The original cross base was quite small. It measured 9 inches high, 13 inches wide and about 9 inches deep. The shaft, a small portion of which remained, was 7.5 inches wide by 3 inches deep.

The two images to the left represent the sides of the base. The side above has a plain central square surrounded by a meander design. The opposite side also has meander design in two panels that are separated by a central undecorated panel.

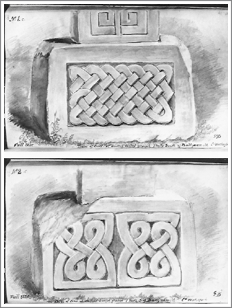

The two images to the right represent the two faces of the base. The face above has a single panel of interlace. On the opposite side there are two panels of interlace side by side.

The two images to the right represent the two faces of the base. The face above has a single panel of interlace. On the opposite side there are two panels of interlace side by side.

Just visible on the shaft fragment in the image above right is what may be a meander or and angular spiral design. There is no carving on the other three sides of the shaft.

(Illustrations from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Figs. 57-60)

It is unclear when the base and shaft fragment went missing but easy to imagine them being carried off without great effort.

Lismore Cross

The Monastery

We know only bits and pieces about the history of the Lismore monastery. It was established by Saint Mochuda, also known as Saint Carthage around the year 630. More will be told of Mochuda, who died in 637, below (see The Saint). Lismore was mentioned numerous times in the Annals of Inisfallen between 701 and 1024. The list of entries provides us with the names of a number of the abbots or bishops of Lismore as well as noting other events of importance in the history of the monastery. (Annals of Inisfallen and Lismore, County Waterford) The photo of St. Carthage Cathedral, Church of Ireland is included as it houses the cross-head. (photo, St. Carthage Cathedral)

• AI701.1 Kl. Repose of Cúánna of Les Mór.

• AI707.1 Kl. Conodur of Les Mór rested.

• AI730.1 Kl. Repose of Colmán grandson of Lítán, abbot of Les Mór.

• AI752.3 Repose of Mac Uige, abbot of Les Mór.

• AI760.1 Kl. Tríchmech, abbot of Les Mór, rested, and Abnér, abbot of Imlech Ibuir.

• AI763.1 Kl. Repose of Rónán, bishop of Les Mór.

• AI768.1 Kl. Aedan, abbot of Les Mór, rested.

• AI774.2 Suairlech, abbot of Les Mór, [rested].

• AI778.2 Repose of Airdmesach of Les Mór.

• AI783.3 Repose of Suairlech Ua Tipraiti in Les Mór.

• AI794.4 Violation(?) of the Rule of Les Mór in the reign of Aedán Derg.

• AI814.1 Kl. Repose of Aedán moccu Raichlich, abbot of Les Mór.

• AI814.2 The abbacy of Les Mór to Flann, son of Fairchellach.

• AI818.2 The shrine of Mochta of Lugmad in flight before Aed,son of Niall, and it came to Les Mór.

• AI825.1 Kl. Repose of Flann son of Fairchellach, abbot of Les Mór, Imlech Ibuir, and Corcach.

• AI833.1 Kl. Les Mór Mo-Chutu and Cell Mo-Laise plundered by the heathens.

• AI867.1 Kl. Amlaíb committed treachery against Les Mór, and Martan was liberated from him.

• AI883.1 Kl. The burning of Les Mór by the son of lmar.

• AI912.1 Kl. Repose of Mael Brigte son of Mael Domnaig, abbot of Les Mór.

• AI920.1 Kl. The martyrdom of Cormac son of Cuilennán, bishop and vice-abbot of Les Mór, abbot of Cell Mo-Laise,king of the Déisi, and chief counsellor of Mumu, at the hands of the Uí Fhothaid Aiched.

• AI938.1 Kl. Repose of Ciarán son of Ciarmacán, abbot of Les Mór Mo-Chutu.

• AI947.1 Kl. A leaf [descended] from heaven upon the altar of Imlech Ibuir, and a bird spoke to the people; and many other marvels this year; and Blácair, king of the foreigners, was killed.

• AI953.2 Repose of Diarmait, abbot of Les Mór.

• AI954.3 Diarmait son of Torpaid, abbot of Les Mór, [rested].

• AI958.3 Repose of Cinaed Ua Con Minn, bishop of Les Mór and Inis Cathaig.

• AI959.2 Repose of Maenach son of Cormac, abbot of Les Mór.

• AI983.3 Repose of Cormac son of Mael Ciarain, abbot of Les Mór.

• AI1024.3 Repose of Ua Maíl Shluaig, coarb of Mo-Chutu.

Lismore was not immune to the Viking attacks of the 9th century. The town and monastery were burned on eight different occasions. (History of Lismore)

Like many of the early monasteries of Ireland, Lismore developed a school that over time produced some notable graduates. Before the end of the 7th century St. Cathaldus founded a monastery at Taranto in southern Italy. In the 12th century Lismore was deeply involved in the reform movement that concluded with the Synod of Rath Breeasail in 1111. Indeed Saint Malachy, Archbishop of Armagh and primate of Ireland, who led the reform movement, was a graduate of Lismore. (History of Lismore)

Nothing seems to be available concerning the decline and end of the history of the Lismore monastery. What we do know is that the Lismore castle was built in 1171 by order of King Henry II of England and completed by 1185 as an Episcopal residence for the local bishop. Whether this indicates the end of the monastery is not known. (History of Lismore)

The Saint

St. Carthage (of Lismore) or Mochuda, was a native of Kerry. His given name was probably Chuda with the Mo was added as a sign of affection, as in my dear Chuda. As a boy he was introduced to bishop Carthage (the elder), from whom the name Carthage may derive. Attracted by the singing of psalms, he followed Carthage and some other clergy and spent the night outside the monastery of Thuaim listening to them sing far into the night. The chieftain of the area Moeltuili, who was fond of Mochuda went looking for him and on finding him and hearing his explanation, sent for the bishop and recommended Mochuda to his care. The bishop took on Mochuda and cared for and educated him until his ordination as a priest. This happened about the year 580. (Lanigan, p. 351)

The image to the right is from (Mochudu bishop of Lismore)

After moving from place to place, Mochuda was encouraged to establish a monastery. He selected a place called Raithin or Rathen, located in Westmeath. This monastery, founded about 590, grew to nearly 900 members. Carthage remained there 40 years and while there wrote a Rule for the community and was consecrated bishop. Due to the “envy of some clergymen or monks of a neighbouring district” the prince of that area expelled Carthage and his monks in 630. (Lanigan p. 352-3)

The expulsion from Rathen was due in large part to the political climate in what is now Westmeath. During the time of Carthage the Eoghanacht of Munster and the Ui Neill of Central Ireland were expanding. Rathen was in ancient Mide (the middle kingdom) and in the orbit of the Ui Neill. It was, however close to the northern reach of the Eoghanacht and Carthage was a Munsterman. It was not acceptable to the Ui Neill to have what could be a Munster outpost in Ui Neill territory. (Ryan)

By 633, a son-in-law to Failbhe Fland (King of Munster) granted him land on which the Lismore monastery was established. Carthage died just 4 years after the establishment of the monastery in the year 637. (Lanigan p. 353)

The Cross

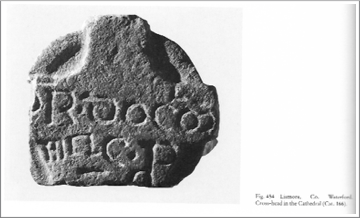

The cross at Lismore is a cross head that is imperforate and ringed. It was found during excavations at Lismore Cathedral and was attached to the interior of the west wall. In 2017 it was being restored and was to be placed in a display that will offer a view of each face.

There is an inscription across the arms that reads “Prayer for Cormac P”. The cross is a little over 6.5” (16.5cm) high by about 7.5” (19cm) wide. See the photo to the left. (Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Fig. 454) The whole cross was probably less than 2’ (61cm) in height.

The Lismore Crozier

The National Museum of Ireland, in Dublin, has a crozier found in the Lismore Cathedral in the early 19th century. It is dated to about 1100, the period of church reform in Ireland. In the competition between major monasteries to become episcopal centers, various treasures were commissioned to reinforce their claims for authority.

The museum website describes the crozier as follows: “It is formed of a wooden staff decorated with sheet bronze, spacer knops, and surmounted by a cast copper-alloy crook. The crook is cast in a single piece and is hollow apart from a small reliquary which was inserted in the drop. Both sides of the crook are decorated with round studs of blue glass with red and white millefiori insets. Three animals with open jaws form the crest of the crozier, and these terminate in an animal head with blue glass eyes. An inscription at the base of the crook records the name of Neachtain, the craftsman who made the crozier, along with the Bishop of Lismore, who commissioned it.” (Museum.ie)

Getting There: Located along the N72 between Dungarvan and Fermoy. The Saint Carthage Cathedral (Church of Ireland) is located on the north side of town. From the N72 take Main street to the east. At S. Mall turn left. The Cathedral is at the north end of S. Mall. The map is cropped from Google Maps.

Resources Cited

(Anals of Inisfallen) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lismore,_County_Waterford and http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/T100004/index.html

County Waterford: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lismore,_County_Waterford, November 2015.

Fenor: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fenor

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey

Historic Environment Viewer: https://webgis.archaeology.ie/historicenvironment/

History of Lismore: http://www.lismore-ireland.com/about-us/history-of-lismore, November 2015.

Irish Megaliths: http://www.irishmegaliths.org.uk/waterford.htm Source of photo above: https://www.prehistoricwaterford.com/products/ballyquin-portal-tomb/

Iron Spearhead: http://100objects.ie/ironspearhead/

Lanigan, John, An Ecclesiastical History of Ireland, 1923.

Lismore, County Waterford: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lismore,_County_Waterford

Matthewstown: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matthewstown_Passage_Tomb

Mochudu bishop of Lismore: http://catholicsaints.info/butlers-lives-of-the-saints-saint-carthagh-or-mochudu-bishop-of-lismore/, 2015

Monastic Houses of Waterford: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_monastic_houses_in_County_Waterford

Museum.ie: (http://www.museum.ie/en/exhibition/list/ten-major-pieces.aspx?article=933dffe0-8d17-4347-bccb-ff5daeb8b861 November, 2015)

National Museum of Ireland, Archeology, Dublin: http://www.museum.ie/en/exhibition/list/ten-major-pieces.aspx?article=933dffe0-8d17-4347-bccb-ff5daeb8b861 November, 2015

Norman Invasion: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Norman_invasion_of_Ireland#Arrival_of_Strongbow_in_1170

O Croinin, Daibhi, ed.; "A New History of Ireland: Prehistoric and Early Ireland", “High-kings with opposition, 1072-1166, Marie Therese Flanagan, Oxford University Press, 2005.

Ryan, John, S.J., Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae, http://omniumsanctorumhiberniae.blogspot.com/2013/05/saint-carthage-of-lismore-may-14.html, November 2015.

St. Carthage Cathedral: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lismore_Cathedral,_Ireland

Tooreen: https://www.prehistoricwaterford.com/products/tooreen-megalithic-complex1/.

Waterford Museum: http://www.waterfordmuseum.ie/exhibit/web/Display/article/312/2/Early_Waterford_History_The_Decies_.html

Woodstown: https://www.prehistoricwaterford.com/products/woodstown-pormontory-fort/

Woodstown wiki: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woodsto