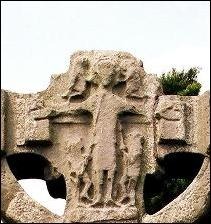

Figural or Pictorial representation: Included in this category are a large set of carvings that depict scenes from the Bible, contemporary life, or in some cases ancient mythological figures. The example below left is the Cross of Muiredach at Monasterboice in Co. Louth. I have divided these into three categories: images from the Hebrew Scriptures, from the Christian Scriptures, and non-biblical images. We will briefly survey each category. First, I want to address briefly the version of the Bible that was in use in the western church in the early fifth century. This was the Bible that was introduced to the Irish.

The Bible in the fifth century: In 807 a scribe of Armagh named Ferdomnach supervised the production of what is now known as the Book of Armagh. This volume contained the story of Patrick, the Gospels and Epistles and a life of St Martin of Tours. “This [book] is revered as being the oldest complete Irish copy of St Jerome’s Vulgate and brings us into contact with the Gospels and Epistles as read in the Early Irish Church.” (Slavin 90, 94, 101) The Vulgate was commissioned by the Pope and completed in about 405 (before the arrival of Saint Patrick in Ireland). It became the standard Latin translation of the Bible. This was, almost certainly, the Bible that was first introduced into Ireland. In the early centuries following its completion, there were very few complete copies. In addition, because it was written in Latin, only those who were well educated would have been able to read the text for themselves. This underlines the importance of the monasteries as educational institutions that preserved, produced and proclaimed the stories and message of the Bible. It also suggests a possible educational role for the so called “scripture crosses” (crosses that contained pictorial images from the Hebrew and Christian scriptures). Viewing these scripture crosses would bring to mind for the literate and non-literate the stories of the bible and to some degree their interpretation or meaning.

The Bible in the fifth century: In 807 a scribe of Armagh named Ferdomnach supervised the production of what is now known as the Book of Armagh. This volume contained the story of Patrick, the Gospels and Epistles and a life of St Martin of Tours. “This [book] is revered as being the oldest complete Irish copy of St Jerome’s Vulgate and brings us into contact with the Gospels and Epistles as read in the Early Irish Church.” (Slavin 90, 94, 101) The Vulgate was commissioned by the Pope and completed in about 405 (before the arrival of Saint Patrick in Ireland). It became the standard Latin translation of the Bible. This was, almost certainly, the Bible that was first introduced into Ireland. In the early centuries following its completion, there were very few complete copies. In addition, because it was written in Latin, only those who were well educated would have been able to read the text for themselves. This underlines the importance of the monasteries as educational institutions that preserved, produced and proclaimed the stories and message of the Bible. It also suggests a possible educational role for the so called “scripture crosses” (crosses that contained pictorial images from the Hebrew and Christian scriptures). Viewing these scripture crosses would bring to mind for the literate and non-literate the stories of the bible and to some degree their interpretation or meaning.

Images from the Hebrew Scriptures: [For a more complete assessment of the Hebrew Scripture texts that appear on the High Crosses see the feature below entitled Hebrew Scripture Images.] As the early Christians sought to understand who Jesus was and the significance of his life, death and resurrection, they turned to the pages of the Hebrew Scriptures. The majority of High Cross scholars would agree with Francoise Henry that most Hebrew scripture scenes on the crosses were selected “either as manifestations of God’s help to the faithful or as ‘types’ or ‘prefigurations’ of an event in the life of Christ.” (Henry 1964, 35)

It might be helpful to note that the Hebrew texts were, of course, the only scriptures available to the Christians of the first three centuries after Christ. The earliest of the documents now contained in the New Testament or Christian scriptures were letters of the Apostle Paul. The first of these was probably written about fifty. While all or most of the books now in the New Testament had been written by 100 or shortly after, it was not until 367 that we find the first list of New Testament books that is identical with those in our New Testament today. In the Hebrew Scriptures, many Christians then and now identify passages and stories in which they see references to Jesus. Here is the reasoning for this method of interpretation according to William Barclay. “It was a Jewish belief that all Scripture had four meanings – Peshat, the simple meaning which could be seen at the first reading; Remaz, the suggested meaning and the truth which the passage suggested to the seeking mind; Derush, the meaning when all the resources of investigation, linguistic, historical, literary, archeological, had been brought to bear upon the passage; Sod, the inner and allegorical meaning. . . . Now of all the meanings Sod, the inner, mystical meaning was the most important. The Jews were, therefore, skilled in finding inner meanings in Scripture. It was thus not difficult for them [the Jews who were the first Christians] to develop a technique of Old Testament interpretation which discovered Jesus Christ all over the Old Testament.” (Barclay, 45)

In this way the Hebrew Scriptures were baptized by early Christians. “For example, Isaac carrying the wood for his sacrifice was paralleled with Christ carrying his cross.” (Henry 1964, 38; text from Genesis 22:1-19)

There are many examples of Old Testament scenes on the High Crosses, but allow the following few to suffice to make the point.

The image on the left is from Muiredach's Cross at Monasterboice (Co. Louth). The image on the right is from the High Cross at Moone (Co. Kildare).

The image on the left is described by Peter Harbison. “Adam and Eve are shown under the arcaded branches of the apple tree, its fruit falling down behind their backs. The serpent coils its way up the tree and turns to Eve on the left, whose right hand proffers the apple to Adam while the left hand hides her shame. Adam, bearded, stretches forth his left hand to receive the apple while using his right hand to hide his shame.” (Harbison 1992, 143; text in Genesis 3) Early Christians came to see the story of the fall as contrasting the first Adam and Christ as the new Adam. “For since death came through a human being, the resurrection of the dead has also come through a human being. For as all die in Adam, so all will be made alive in Christ.” (NRSV 1 Corinthians 15:21-22) The image of the Fall served as a reminder of the problem of human sin and at the same time foreshadowed God’s solution to that problem in Jesus Christ.

The image above right represents the story of Daniel in the Lion’s Den. The text can be found in chapter 6 of the book of Daniel. In the image we see Daniel as the central figure with three lions on his left and four on his right. In the text angels protect Daniel from harm.

Images from the Christian scriptures: [For a more complete assessment of the Christian Scripture texts that appear on the High Crosses see the features below entitled Christian Scripture Images; Imaages of the Fall, Biblical or Secular Images; Holy Week Images; the Crucifixion and the Resurrection.] Depictions of the crucifixion appear more often than any other image from the Christian scriptures. These scenes are almost always in the center of the head of the cross. In a good number of these we see the figures of “Stephaton the sponge-bearer and Longinus with his lance.” (Harbison 1992, 273) These are the names traditionally given to the two Roman soldiers, the first of whom offered Jesus a sponge filled with wine and the second of whom pierced Jesus’ side after he had breathed his last. In the examples to the left and right these figures appear in one but not in the other. The left image is from the west face of the Unfinished cross at Kells (Co. Meath), while the right image is from the east face of the west cross at Kilfenora (Co. Clare).

Not surprisingly, the apostles are another popular theme on the Irish High Crosses. On the cross to the left, from the Tall Cross at Monasterboice (Co. Meath), they appear grouped in four successive panels. On the cross to the right, Moone (Co. Kildare) the apostles are grouped together on the base of the cross. These images offer an excellent example of scenes that are not related to any particular biblical text. The apostles are recognized only by the fact there are twelve of them in the group.

Another Christian image, not directly connected to one particular text, is the Last Judgment. There are a number of texts this image might be related to including Matthew 25: 31ff, The Judgment of the Nations. One of the finest examples of the Last Judgment is found on the Cross of Muiredach at Monasterboice (see below). Kees Veelenturf writes that this cross has the most elaborate depiction in Irish art of the Last Judgment. (Veelenturf 104-107)

Peter Harbison describes the scene: “In the centre, Christ stands with outspread feet and wearing a long robe to below the knees. There is an eagle above his head, with its head to the left and its left wing expanded. Christ carries a cross-staff over his left shoulder, and a blossoming scepter over his right. To the left of his feet there is a kneeling angel holding a book, and with another book above its head. Beside the angel, and looking to the right towards Christ, a harper – presumably David – sits playing the instrument which rests on his knees, while a bird perches on top of it and whispers into his ear – the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. Behind him is a man playing a flute-like wind instrument, while behind him again there is a man with an open book, probably to be understood as singing. The south arm is taken up with a number of seated or kneeling figures in long garments – the good who have been saved and who deserve a place in heaven.

“To the right of Christ there is a seated musician with something flat (an instrument?) on his lap as he plays a three-reeded pipe. He is presumably one of David’s musicians. To his right, a bearded devil – holding a trident – herds the evil souls, in all their nakedness, towards their eternal damnation in hell. The first of these figures is a curious kneeling figure with the lower legs splayed sideways, to the right of which there is a figure with a book. The north arm is occupied by the bad souls.” (Harbison 1992, 141-2)

Non-Biblical Images: There are quite a variety of non-biblical images on the High Crosses. Some of these are religious in theme and others are not. Under the first category we have images that have been identified as various saints including St. Anthony (a desert father), St. Brendan (the Navigator) founder of Clonfert monastery, St. Columcille founder of Iona and many other Irish monasteries, and of course St. Patrick. The following photos each present a story about Saint Paul the Hermit and Saint Anthony of the Desert. While Anthony was visiting Paul “they noticed with wonder a raven which had settled on the bough of a tree, and was then flying gently down till it came and laid a whole loaf of bread before them. They were astonished, and when it had gone, ‘See,’ said Paul, ‘the Lord truly loving, truly merciful, has sent us a meal. For the last sixty years I have always received half a loaf: but at your coming Christ has doubled his soldier's rations.’” (Saint Jerome) The cross on the left is the Moone High Cross (Co. Kildare), the one on the right is from the South Cross at Castledermot (Co. Kildare).

The later, mainly twelfth century crosses sometimes depict bishops or other ecclesiastical figures. In the year 1111 an all-Irish church synod was held at Rath Breasail. At this meeting the first diocesan structure for all of Ireland was established. This shifted the balance of power in church politics from the Abbots to the Bishops. While scholars debate whether the ecclesiastic images on some of the twelfth century crosses represent bishops, abbots or Christ as the bishop of the world, the results of the Synod of Rath Breasail suggest these images represent bishops in their role as the vicars of Christ. The two twelfth century crosses below offer representations of this type of image. On the cross to the left, from Dysert O’Dea (Co. Clare) the figure of the bishop is just below the image of the crucified Christ. On the cross to the right, from the Doorty Cross at Kilfenora (Co. Clare), the bishop is the main feature of the east face of the cross. A crucifixion scene appears on the west face of the head of this cross. The illustration on the right is an artists rendering of the image on the Doorty High Cross at Kilfenora, (Co. Clare). It appears on an interpretive sign at the site and shows the image clearly.

There are also figural images on some of the Irish High Crosses that may not be religious in content. The east face of the base of the Cross of the Scriptures at Clonmacnois (Co. Offaly) offers an excellent example. Here is how the scene on the lower panel of the base is described by Peter Harbison: “Two chariots, with large 8-spoked wheels, and probably drawn by two horses apiece, proceed toward the right. In addition to the charioteer, who holds the reins, there is one passenger in each vehicle.” The photo is also from Peter Harbison. (Harbison 1992, vol. 1, 48; vol. 2 photo) Harbison notes on the same page that at least one scholar has sought to identify this image with the Exodus.