The crosses of County Carlow include: Clonmore North Cross, Clonmore South Cross, Garryhoundon, Kildreenagh/Newtown Cross, Lorum Cross, Nurney Cross, Old Leighlin, Orchard Cross, St. Mullins Cross, Tullow or Templeowen Cross and Watertown Cross. County Carlow is located with a star on the map to the right.

The Dynasties of County Carlow and County Wexford: 400-1200 CE

The establishment of counties in Ireland began under King John of England in 1210. Prior to that date; in the period that includes the coming of Christianity to Ireland, the establishment of monasteries and the carving of High Crosses; Ireland had many different tribal dynasties that were dominant in various areas of the island. In the province of Leinster, in the area of the current counties of Carlow and Wexford, there were several dynasties that were dominant between 400 and 1200 CE. The following is a brief survey of some of the tribal groups.

Around the year 400 CE, the century when Christianity seems to have first come to Ireland, the Ui Bairrche and the Ui Gabla seem to have dominated the area in southeastern Leinster that includes County Carlow.

In the mid-seventh century the Ui Bairrche were under the control of Bangor in the northeast. It was during the seventh century that the Ui Chennselaig tribe began to expand and dominate the area that includes the modern counties of Carlow and Wexford.

The Ui Chennselaig traced their heritage to Enna Cennselach (Enna the Dominant). They probably originated in the valley of the River Barrow. Their early capital was in Rathvilly, County Carlow. Near Rathvilly, at Watertown, there is a fragment of a High Cross, but no remains of a monastery or royal centre remain at Rathvilly. The Ui Chennselaig later expanded southward and had a base around St. Mullins on the River Barrow, also in County Carlow. There is a ninth century High Cross at St. Mullins and the remains of a monastary

By the ninth century the Ui Chennselaig power center had moved to the east and their tribal center was at Ferns in the present county of Wexford. This royal capital was also the site of an active monastery, and of course, ecclesiastical leadership was intertwined with political leadership. For example, Cathal mac Dunlainge is titled “rex nepotism Cennselaig et secant Fernann” (king of Ui Chennselaig and prior of Ferns). There are several High Crosses at Ferns.

In the year 1042, Diarmait mac Meal-na-mBo established himself as King of all Leinster. His family took the name of Mac Murchada (Mac Murrough). A later relative, Diarmait Mac Murchada was deeply involved in the politics of the twelfth century that resulted in the “invasions” of the English into Ireland.

The map below is one of many that are part of “Ireland’s History in Maps” (http://sites.rootsweb.com/~irlkik/ihm/ire400.htm) It shows that in about 700 CE the Ui Chennselaig were the dominant tribal dynasty in southern Leinster. The Ui Bairrche had become a more minor tribal group.

Ecclesiastic History

The Christian faith seems to have arrived in what is now County Carlow in the late 5th century. Three of the monasteries listed below; Domnach-feic, Kilfortchearn, and Tullow, were founded in this first century of the expansion of the faith into Ireland. The list below does not, however, include all the sites that have high crosses. Missing are: Garryhoundon, Kildreenagh/Newtown, Nurney, Orchard, and Watertown. These, along with Clonmore, Lorum, Old Leighlin and Tullow, will be discussed below.

The listing of monasteries below was found at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_monastic_houses_in_County_Carlow

Agha MonasteryGaelic monks, founded in 6th century by St. Fintan

Carlow MonasteryGaelic monks, founded pre 601 by St. Comgal of Bangor

Clonmore MonasteryGaelic monks, founded in 6th century by St. Mogue, church burnt 1040

Domnach-feic Monastery Early site founded in 5th century by St. Fiace

Kilfortchearn Monastery Early site founded in 5th century by St. Fortchern

Leighlin AbbeyGaelic monks, founded c.600 by St. gibbon, destroyed by fire c. 1060

Lorum MonasteryGaelic monks, patron St. Laseroam (Molaise)

St. Mullin’s Monastery Gaelic monks, founded in 632 by St. Molling

Tullow MonasteryEarly site, founded in 5th century

When the Irish church was reorganized in the style of the Roman church at the Synod of Rath Breasail in 1111, Leighlin was established as a diocese with a bishop. At the Synod of Kells in 1152, the diocese of Leighlin was placed in the Province of Dublin.

Clonmore Crosses

The old monastic site at Clonmore in County Carlow has numerous remains from the Early Christian period in-spite of the absence of any remains of a church or other buildings. In addition to crosses there are an ogham stone, two bullauns, a “font” and a number of cross-decorated slabs.

History of the Monastery

Some time in the sixth century, perhaps about 560, St. Mochaemog (Mogue) founded a monastery at Clonmore. Harbison points out that this Mogue is not to be confused with a saint of the same name at Ferns in Co. Wexford. (Harbison, 1991, p. 178) One estimate, not footnoted, suggests that as many as 5000 monks and scholars may have lived there at the height of the monasteries prestige. (McDonald)

Legend tells us that a St. Onchuo, a contemporary of Mogue was responsible for the presence of a great treasure of relics of the Saints of Ireland at Clonmore. It is told that Onchuo was interested in history and spent years traveling around Ireland to places of ecclesiastical importance collecting history and relics from church leaders noted for sanctity. These he brought to Clonmore seeking a relic from St. Mogue. Mogue denied the request but immediately one of his thumbs dropped off as if severed and was added to the collection of relics. While Onchuo, also known as Aedus and Aidenus may never have existed, the story suggests that Clonmore did in fact have a large quantity of relics of early Irish saints. (Harbison, 1992, p. 178; McDonald)

Comerford and McDonald mention a number of other saints associated with Clonmore. I presume these saints are named in the Martyrology of Tallaght, though this is not specifically stated. The list includes:

St. Finan, who is also associated with the abbeys of Innisfallen in Kerry and Ardfinane in Tipperary, who may have been abbot at Clonmore following Mogue;

St. Brogan Cloen who lived at Clonmore, perhaps between 620 and 650. He composed a hymn in praise of St. Brigid while there;

St. Stephen or Straffan who is also mentioned as succeeding St. Mogue around 615. He is another saint who may or may not be associated with Clonmore in Co. Carlow;

St. Ternoc or Ternog: While he is mentioned in the Martyrology of Tallaght and may be associated with Clomore in Carlow or a Clonmere elsewhere; (omniumsanctorumhiberniae)

St. Lassa or Lassair;

St. Dinertach, or Dinertach ail “the bashful”;

and St. Cumman are also mentioned in connection to Clonmore.

In the Annals of the Four Masters we find the names of several other leaders of the Clonmore monastery. They advance the history of the monastery into the late tenth century.

M767.2

Aerlaidh of Cluain Iraird Clonard, died.

M877.6

Ferghil, Abbot of Cluain Mor Maedhog;

M886.3

Seachnasach, son of Focarta, Abbot of Cluain Mor Maedhog;

M919.5

Cairbre, son of Fearadhach, head of the piety of Leinster, successor of Diarmaid, son of Aedh Roin, airchinneach of Tigh-Mochua, and an anchorite, died, after a good life, at a very advanced age;

M920.4

and Ailell, son of Flaithim, Abbot of Cluain-mor-Maedhog, died.

M972.6

Cairbre, son of Echtighern, comharba of Cluain-mor-Maedhog, died.

Like most early Irish monasteries, Clonmore was sacked or burned at times.

The last recorded raid may have marked the end of the monastery. It marked the end of Diarmait’s “power struggle against Mac Murchada relatives who were using Clonmore as a base from which to challenge Diarmait’s succession to the kingship of south Leinster.” (Harbison, 1991, p. 179)

The Crosses

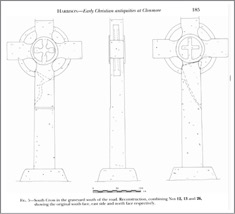

The North Cross

The North Cross is carved of granite and has an imperforate ring. It is variously referred to as St. Mogue’s Cross and the Mission Cross. The North Cross is carved of granite and has an imperforate ring. It is variously referred to as St. Mogue’s Cross and the Mission Cross. The cross stands 7.4 feet (2.25m) tall by 4 feet (40cm) across at the arms. It is 8 inches (21cm) thick. It now lacks the top arm or head of the upright. Unlike most Irish crosses the North and South crosses at Clonmore are oriented north - south rather than east - west. The only possible decoration that can be discerned is a possible spiral decoration that Harbison describes as “above the centre of the north face.” (Harbison, 1991, p. 191)

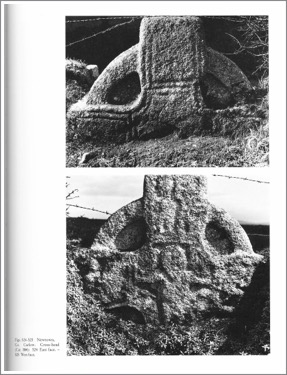

The South Cross

The cross-head, or South Cross, at Clonmore is carved from granite and is buried head down in the ground. The cross-head is ringed and imperforate and measures 5 feet 2 inches (1.58m) across the arms. There are hollowed armpits on the cross. Other fragments shown to belong to the original cross allow for a reconstruction of most of the cross. This is illustrated in the image to the left. (Harbison, 1991) The photo above right shows the north face of the cross-head.

The base and shaft are shown below right. On each face, in the center of the head is a raised circle with a cross inside. On the north face, as pictured above right, there is a Latin cross. This cross is attached to the circle only at what was the bottom of the ring. On the south face, as pictured below left, is a Greek cross with equal arms that expand from the center to the inside of the ring.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 45, 4 D. From the N81 between Baltinglass (3 C) and Tullow (4 C), take the R727 east. Five to six km after you turn onto the R727 there will be a signposting to Raheen, the Ballykilduff Road. Follow this for 2.1 km. Next follow the Ballinakill Road for 3.4 km.to Clonmore. See the map to the right. The road divides the two parts of the old monastery. North of the road is St. Mogue’s Cross and south of the road a series of stones fragments have been collected among which are the other high cross pieces mentioned above. The base and shaft are south of the cross-head.

Map detail right from Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Annals of the Four Masters, http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/T100005B/index.html

Comerford, M., Collections Relating to the Dioceses of Kildare and Leighlin, Volume III, (Dublin, 1886), 178.

Harbison, Peter, “Early Christian Antiquities at Clonmore, Co. Carlow”, Proceedings of the royal Irish Academy, Section C: Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature, Vol. 91C (1991), pp. 177-200.

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Historic Environment Viewer: http://webgis.archaeology.ie/historicenvironment/

Marcella, http://omniumsanctorumhiberniae.blogspot.com/2013/07/saint-ternoc-of-cluain-mor-july-2.html.. Recovered 12/9/16.

McDonald, Eddie, “The Riches of Clonmore”, Clan O’Byrne The Official Homepage. http://www.clannobyrne.com/the-riches-of-clonmore.http

Garryhundon Cross

This cross is located in the Killogan burial ground that may be the site known as Cill Eogain. The site is uncultivated and enclosed by a fence. I find no history of the site. (Historic Environment Viewer)

Harbison describes the cross as ringed and imperforate. It stands 4.5 feet (1.35m) tall is 34 inches (87cm) across the arms and 7 inches (18cm) thick. A raised boss decorates the center of the head. The base of the cross is nearby and stands 8.6 inches (22cm) high. (Harbison, 1992, p. 94) The cross and base are pictured to the right.

Kelly suggests a relationship between this cross and those at Tullow, Orchard and Nurney. All are closely grouped and have “continuation of the edge moulding which defines the ring across the face of the cross where it may be traced crossing the arms and upper and lower shaft.” (Kelly, p. 65) She also points out that they all have solid rings and raised bosses in the center of the head. The group probably dates to the 10th century.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas p. 45 B 5. Take exit 6 on the M9 south of Carlow (4 B). Take the R448 south toward Leighlinbridge. After about 0.6km turn left for less than 3km and follow the map to the right to the Killogan Burial Ground marked with a white circle on the map to the right. You will be on the east/west road just below the white circle.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Resources Cited:

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Historic Environment Viewer ( http://webgis.archaeology.ie/historicenvironment/ )

Kelly, Dorothy, “Irish High Crosses: Some Evidence from the Plainer Examples,” The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 116 (1986), pp. 51-67.

Lorum Cross

The Site and the Saint

The presence of a cross base and partial shaft of a high cross are the only evidence that there was a monastery or church at Lorum in the early medieval period. Tradition tells us that at one time St. Laserian was honored as the patron saint of Lorum, but he was not directly associated with Lorum except in a story that he wanted to build a monastery there but was directed by the Spirit to Leighlin instead.

The photo to the right shows the landscape west of the Lorum church with the cross-shaft fragment in the cairn of stones in the foreground.

St. Laserian was brother to St. Goban and succeeded him as abbot of Leighlin in 637, one year before his death in 638. Laserian was educated by Abbot St. Murin and was ordained in Rome by Pope Gregory the Great. He was a proponent of the Roman dating of Easter and was ordained a bishop by Pope Honorius who made him legate to Ireland.

The Cross-shaft

There is a carved pillar that may have been part of the shaft of a cross located in a cairn of stones on the edge of a field about 200 yards west of the Lorum Church. It stands about 37 inches high and is about 12 inches wide and 5 inches thick. Harbison notes that the west face has two panels, the upper one of which is divided into four squares. It appears there was once a figure sculpture in each of these squares but no content can now be discerned. The lower panel may have had an animal turning to the left. It is possible the east face was also decorated but there is no surviving sign of this. s(Harbison, 1992, p. 138)

In the photos above the west face of the cross is visible in the left photo and the east face in the right side.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 53 B 1. Just south of Bagenalstown (on the R705) take the L3001 to the southeast for between four and five km. Turn right or south on an unnamed road that goes to Raheenduff. The Lorum church is there. The cross shaft is in a field about 200 yards west of the graveyard behind the church. Follow a farm road and the cross shaft will be in a pile of stone to your right. The site is marked on the map to the right with a white circle.

Map detail right from Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Butler, Alban, The Lives of the Saints, Volume IV, April, 1866 “St. Laserian, Called Molaisre, Bishop of Leighlin, In Ireland,”

Catholic Online: “St. Laserian,” http://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=4195.

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

pilgrimagemedievalireland, “St. Laserian at Lorum, Co. Carlow,” https://pilgrimagemedievalireland.com/2016/04/20/st-laserian-at-lorum-0co-carlow/.

Newtown or Kildreenagh

I found no information whatever concerning the presence of a church or monastery near the site of the cross-head at Newtown (Kildreenagh township). Thus there is nothing to explain the presence and location of the cross-head under consideration. Harbison describes the cross and I follow his lead. See Harbison, 1992, pp. 157-158.

The cross-head is carved of granite and stands about 39 inches in height and has an arm span of just under 4 feet. This places it in the same size category as the County Carlow crosses at Clonmore, Nurney and the cross-head at Tullow (Templeowen). Like each of these other crosses, it has a ring that is imperforate.

The head and the panels that are visible on the top and the arms have roll mouldings.

Shaft: A portion of the shaft is visible and it has interlace that is framed by roll moulding.

Head:

East Face: This face has roll mouldings and framed panels but there is no apparent carving. See the upper right photo.

West Face: The west face has a crucifixion scene in the center that includes the traditional figures of Stephaton and Longinus below Jesus’ arms and an angel above each arm.

Each arm of the cross-head has a scene that could be from the life of King David. Each is difficult to identify though Harbison makes a suggestion for each. The south arm (to the right in the lower photo above) seems to show David slaying a lion. The north arm (to the left in the lower photo above) probably illustrates David playing the harp. The top arm, as Harbison notes, is best left unidentified but on comparison with the cross at Ullard, it might suggest David’s encounter with Goliath. (photos, Harbison 1992, Vol. 2, Figs. 524, 525)

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 45 5 B. Located south of Carlow (4 B) and east of Bagenalstown (5 B). From the R448 take the R724 east toward Fennagh. About 5 to 6 km along the way take a left. R724 bends south then turns sharply back east at this intersection. When you come to a “T” in the road (about 2.5km), go right or east. When you come to the next “T” (about 1km) go right again or south. The site is between 100 and 200 meters south of this turn. The cross is built into a field fence on the east or right side of the road. I was unable to find this cross.

Map detail right from Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Nurney

The Site

The church grounds and surrounding L-shaped field were part of an early monastery. A 2001 survey showed the earliest monastic buildings date to the 5th century. The buildings of the 5th century monastery included a small rectangular plan church and four round support buildings.

In the 6th and 7th centuries another seven round buildings were added. They had clay and wattle walls with a thatched conical roof.

Pictured to the right is the current Nurney church.

The 8th century saw the addition of two churches and the high cross. This wording almost certainly refers to the cross in the field behind the church and does not attempt to explain the cross-head in the front of the church (see below).

In the 9th century a dormitory that would have accommodated about 12 monks was constructed.

In the 10th century a stone T-shaped churches was built. The walls were three feet thick and the roof was thatched. This building was used for several centuries as the parish church. Nearby was a stone house where the priest presumably lived.

The 11th century saw the construction of a scriptorium, dormitory and guest house.

The 12th century witnessed the construction of a church. There was also a monks burial ground that was presumably used over an extensive period of time. (Nurney, pdf)

The results of the archaeological survey suggest that the monastery at Nurney was active over a period of at least six to seven hundred years. The survey report does not address the history of the monastery or church beyond the twelfth century.

The Saint:

Tradition attributes the foundation of the church at Nurney to Saint Abban (Abban moccu Corbmaic) who died about 520. Alban’s primary connections are with Mag Arnaide (Adamstown) in County Wexford and Cell Abbain or Killabban in county Laois.

The Lives state that Abban made two trips to Rome during his life. It was after the second trip that he established a number of churches, including Nurney. The Lives also claim he was the son of Cormac, son of Ailill, king of Leinster and that his mother was Milla, a sister to Saint Ibar, one of the pre-Patrick saints and patron saint of Co. Wexford.

The Crosses

The Nurney Cross

The cross described by Harbison is located in a field behind the church. It stands six feet two inches (1.9m) tall and three feet seven inches (1.1m) across the arms. It stands on a base that is just short of two feet (60cm) tall. The head is ringed and the ring is imperforate. The edges of the cross have roll moulding. There is a large boss on each face of the cross in the center of the head. There may have been panels on the shaft but the only possibly discernable image could be Saints Paul and Anthony Breaking Bread in the Desert. This may be at the top of the shaft on the south face. Harbison suggests that only the eyes of faith can imagine this image. (Harbison, 1992, p. 158)

The photo to the left is the south face of the cross. That above right is the north face.

The photo to the left is the south face of the cross. That above right is the north face.

The Cross-Head

The cross-head that stands in front of the church is nowhere described and may not be early as it is not mentioned by Harbison. Like the cross described above it has a ring that is imperforate. It is not possible to discern any signs of carving on either face of the cross.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 45 B 5. Located south of Carlow (4 B). From the R448 north of the M9 turn left onto an unnamed road heading east. After you cross the M9 take the first right and go south for about four km. Take a left (east) on the Tullow Road. Nurney is about four km along the road. As you come into Nurney the Protestant Church is on the left. The cross is in a field behind the church, indicated on the map to the left by the large circle..

Map detail right from Historic Environment Viewer.

Resources Cited

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Medieval Monasteries, Parish of Bagenalstown, Cara De v. 1, issue 3 (glasnost.itcarlow.ie/ feeleyjm/monastery/nurney.pdf)

Saint Abban: http://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=516.

Old Leighlin

The granite cross, pictured to the right, is located at Saint Laserian’s Well to the west of the present Church of Ireland. It stands 1.28 metres tall and has a pierced ring. There is no trace of any decoration. (Harbison 1992, p 161) The setting is quite lovely and obviously well maintained.

The monastery here was founded by Saint Gobanus, probably in the early 7th century. It became associated with Saint Laserian or Molaise. For most of its history it was a double monastery (monks and nuns). It is said to have grown across the centuries to house as many as 1500 monks. (Old Leighlin, J M. Feeley & J. Sheehan)

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 45 A 5. Located south of Carlow (4 B) and west of Leighlinbridge (5 A). From the R448 south at Leighlinbridge take the Balyknockan Manor Road west. Go through Old Leighlin and past the Protestant Cathedral on the left. After about 200m you will come to a parking lot on your left. There is a path that leads down to the well and the cross. The site is indicated by the large circle on the map to the right.

Map detail right from Historic Environment Viewer.

Resources Consulted

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Feeley, Joseph M. and J. Sheehan. “Old Leighlin monastery and cathedral, 5th to 15th century”, Carloviana 52 (2003), pp. 9-15

Orchard Cross

The nature of the site where the Orchard cross base and cross-head are located is unknown. There are no building remains. There was once a Holy Well in the same field, but that has been covered by road expansion. (National Monument Survey, CW012-044001-) It is not clear whether there was ever a monastery or church on the site.

The cross-base and cross-head of Orchard are located in what was once known as “The Church Field” according to Crawford. (Crawford, 1907, p. 218) This suggests the possibility that there was once a church on the site. The field is located about three quarters of a mile north of Leighlin Bridge.

“There is not any inscription except as shown in the illustration. (see below right). A panel is on the shank, and a double groove round the head. The stone is much worn, but the remains of a face can be traced on the front ‘boss’. The boss on the side of the base is plain” (Vigors, p. 86)

Harbison’s description differs from that of Vigors related to the head or face carving. Harbison states that on the boss or protuberance on the base there is a head carved “on the upper face.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 161; photo above left Vol. 2, Figs. 537-583)

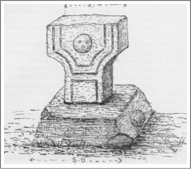

A drawing of the base, referred to above, was published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland in 1892. It is pictured to the right. (Vigors, p. 86)

The top area of the cross is missing.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 45 B 5. South of the M9 and north of Leighlinbridge, the road runs near the river. This area is indicated in the map to the left. The base and cross head are located just off the road at the south end of a driveway. The location is indicated by the small black dot on the map.

Map detail left cropped from Historic Environment Viewer.

Resources Cited

Crawford, Henry S., “A Descriptive List of the Early Irish Crosses”, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 37, No. 2 [Fifth Series, Vol, 17] (June, 30, 1907), pp. 187-239.

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

National Monument Survey, County Carlow, High Cross, Orchard, CW012-044001.

Vigors, Philip D., “Report of the hon. Local Secretary of the County Carlow, for the Year 1892”, The Journal of the royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 3, No. 1 (March, 1893), pp. 86-88.

Saint Mullin’s

The Saint and the Site:

Tradition holds that a monastery was founded in the 7th century at St. Mullin’s by St. Moling, after whom it takes its name. Moling, also called Maidoc or Aiden or Mo Ling was said to be a prince, poet, artist and artisan. Like many saints, he was descended from royalty, in his case Crimthann Cas, the first Christian King of Leinster.

The monastery was established along the River Barrow, a natural highway that allowed for easy communication up and down the Barrow. Indeed the monastery at Leighlin was not far up the river and that of Ros-mic-treoin (New Ross) was nearby down the river. Of course the Barrow also allowed access for the Vikings who attacked the monastery in 824 and again in 951.

The raid that occurred in 951 is recorded in the Annals of the Four Masters “The plundering of Teach-Moling from the sea by Laraic.”

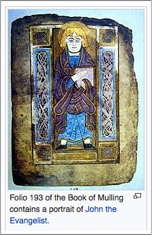

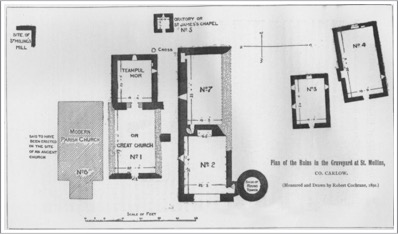

One reason for the attacks of the Vikings was the growth and success of the monastery. In the 8th century an illuminated Gospel, the Book of Moling, may have been produced at St. Mullin’s. (The book is associated with St. Moling but I find no information concerning the place of its production.) This in itself would suggest a rich and successful monastery. On one of the pages there appears a diagram of the monastery that suggests that there were numerous high crosses located there. The diagram, pictured below, shows 12 crosses as follows:

Outside the walls of the monastery:

Southeast: Cross of Saint Mark and Cross of Jeremiah

Southwest: Cross of Saint Matthew and Cross of Daniel

Northeast: Cross of Saint Luke and Cross of Isaiah

Northwest: Cross of Saint John and Cross of Ezekiel

On the wall and within the monastic wall:

Cross of the Holy Spirit

Cross . . . with gifts

Cross . . . with angels from above

Cross of Christ with his apostles

The presence of so many high crosses, if in fact any or all existed, would be an additional suggestion of the wealth and prosperity of the monastery. However, Lawrence Nees, whose diagram appears above, has suggested that this drawing “derives from Carolingian manuscript illumination rather than a plan of an Irish monastery.” (bill.celt.dias annotation)

If we reject the argument of Nees and assume the colophon drawing represents the St. Mullin’s monastery as it was or was hoped to become we might well wonder whether the existing cross is one of those listed above. From location alone it could conceivably be the Cross of Christ with his apostles. This cross was located in the northeast quadrant of the monastic settlement. In the diagram of the present ruins below the existing cross is clearly on the east side of the site and toward the north. However, from the description offered below by Harbison this would seem unlikely unless the missing shaft section focused on the apostles. If this is so, and given the 8th century dating of the Book of Moling and the 9th century dating of the cross, it would be necessary to suggest that the monastic diagram was a later addition to the Book of Mulling.

On the other hand, if Nees is correct, the present cross probably has no relationship at all to the crosses of the diagram.

Saint Moling was a significant member of the Irish clergy. After serving as abbot of St. Mullin’s he became bishop (some would say archbishop) at Ferns in 691. He died five years later in 696.

It is said that in the building of St. Mullin’s Moling was assisted by Goban Saor, who was a legendary Irish builder. He was reported to have been involved in the building of many monastic buildings as well as secular structures. Whether he existed or not there were certainly master builders, both of wood and stone, in early Christian Ireland.

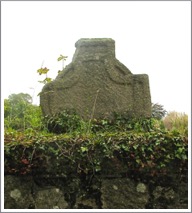

The Cross

The cross is carved of granite and in its present form stands 4 feet 9 inches (1.45m) in height. With the north arm that has broken off it would have been about 39 inches (1m) across the arms. Harbison points out that what we have is only part of the original shaft. There is an imperforate ring. The descriptions below follow Harbison. (Harbison, 1992, p. 165)

Base: The base is round and has a diameter of 35 inches (89cm) and stands 22 inches (56cm) high. There is a panel of decoration on the east side of the base.

East Face: E 1: On the shaft it is just possible to make out two figures. Comparing this image with other Barrow Valley crosses they may represent apostles.

Center: A crucifixion scene has Jesus in a long robe. What appear to be heads below each arm are likely intended to be Stephaton and Longinus. Those above the arms are probably intended as angels.

South Arm: A single figure could be Mary the mother of Jesus.

North Arm: This arm is missing.

Top: There are three figures who might be identified as the three women coming to the tomb. This would be comparable to the same position on the South Cross at Castledermot.

South Side: There is a band of interlace on the shaft and two grooves form a kind of sunken panel in the center of the ring. There is a panel of interlace on the end of the arm.

West Face: Part of this face of the cross has been broken away. In the center was a circular raised moulding. On the arm are horizontal C-shaped spiral patterns.

North Side: There is a panel of triangular fretwork and the underside of the arm is the same as on the south side.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 53, B 3. Located south Graiguenamanagh (2 B) take the R703 east to the junction with the R729. Turn right or south. At Glynn take an unnamed road southwest toward Saint Mullins (3 B).

The map to the left is cropped from the National Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted:

French, J.F.M., The Journal of the royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 2, No. 4 (Dec., 1892), pp. 377-388.

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Nees, L, “The Colophon Drawing in the Book of Mulling: a Supposed Irish Monastery Plan in the Tradition of Terminal Illustration in Early Medieval Manuscripts”, Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies (CMCS) 5 (Summer 1983), p. 69.

Nees, L., synopsis: https://bill.celt.dias.ie/vol4/displayObject.php?TreeID=1613.

Roundtowers: http://roundtowers.org/st_mullins/index.htm.

St. Mullins: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Mullin's

Tullow or Templeowen

A cross-head is now mounted at the top of a wall around a disused graveyard. It stands above an old well at the eastern end of the cemetery. This cross-head originally came from the townland and burial place called Templeowen (St. John’s Church) where there was once an Augustinian Abbey. Since the Augustinians did not arrive in Ireland until the late 13th century the cross may have had its origins at an earlier Celtic monastery or church site. In the late 19th century the cross was lying prostrate on the ground at Templeowen. (Archdall, p. 65)

The Cross-head:

The cross-head is made of granite and measures about 40 by 43 inches (101-109cm). It is 10 inches (25cm) thick. The cross-head is ringed and the ring is imperforate. Two raised bands form the ring and made a complete circle. The edges of the head are outlined by a flat moulding. (Harbison, 1992, p. 178)

This cross is listed twice on the National Survey of Monuments, once in its present location and again under High Crosses related to its presumed original location.

The photo to the left shows the old holy well and the west face of the cross-head; that to the right shows the east face.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 45 4 C. At town centre in Tullow (4 C) the N81 crosses a bridge over the River Slaney. The street on the northeast side of the bridge heads southeast. After about 300 feet, you will see the river and a park area on the right. There is a footbridge across the river and a disused cemetery. The cross is mounted on the cemetery wall. See the map below.

The map to the right is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Archdall, Mervyn, Monasticon Hibernicum or, A History of the Abbeys, Priories, and other Religious Houses in Ireland, Vol. 1, Dublin, 1873, p. 65.

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Watertown Cross

There does not appear to be any history of a monastic or other ecclesiastical site at Watertown. The megalithomania.com site suggests the crosses are a Christianization of an ancient cairn. There are two crosses at the site. One of these, a ringed cross, is reported and described by Harbison, The other, a very small cross that stands beside the first is described briefly in the megalithomania site.

Ringed Cross:

The cross is carved of granite and stands about 6 feet 4 inches (1.9m) in height and measures 34 inches (86cm) across the arms. The cross stands on a base that is 28 x 28 inches(71cm) at ground level. The cross has an imperforate ring, the arms rise slightly and there is roll moulding at the edges. (Harbison, 1992, p. 184)

Small Cross:

Only the rough shape of a cross can now be discerned on this stone. It stands about 2 feet (61cm) in height and whatever arms were once part of the sculpture have been broken off. On one side of the cross is a crucifixion in high relief. Above Jesus’ head is a simi-rectangular shape, also in high relief that has signs of carving on it and may represent the accusation written above Jesus’ head, “This is Jesus the King of the Jews.” (Matthew 27:37). On the top arm of the cross there is a trefoil design. (description and photo: megalithomania.com)

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 45 3 C. Located east of Carlow (4 B) near the junction of the R726 and the N81 just north of Rathvilly. Go into Rathvilly and take a road listed on the map as Phelan street. Go east about one km then turn left onto an unnamed road. Follow this north for about one km. Just before you come to an intersection with a road heading east, look to your left. There is a mound in the field. The cross is on that mound. On the map to the right it is marked by the white circle.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Waterstown: Cross: http://megalithomania.net/show/site/1163/waterstown_cross.htm.