There is only one High Cross in county Cork. It is the Kilnaruane shaft near Bantry. The location of County Cork is indicated by the star on the map to the right.

Historical Background of County Cork

Throughout history, what is now County Cork was part of the Kingdom of Munster. It’s history is tied up with the history of Munster and this review of the history of Cork will spill over to include the entire province. Because this is an introduction to a discussion of the one possible Irish High Cross located in County Cork, the main area of interest is extreme south western County Cork, in the area around Bantry. We begin with a focus on that area.

Fifth Century: Early in the Christian period, in the 5th and 6th centuries, the Corcu Loigde were the most influential tribal group in Munster. They took their name from Lugaid Loigde, “Lugaid of the Calf Goddess”, a King of Tara during the mythological period. Their dominance ebbed away with the rise of the Eoganachta, beginning in the early 7th century. The Corcu Loigde continued as a minor tribal group in extreme southwest County Cork. They had continuing influence during the time when the one possible High Cross know in County Cork was probably carved, the 8th or 9th century. During the period of their greatest influence, the Corcu Loigde subject peoples included the Muscraige, who by shifting their allegiance to the Eoganachta, were influential in the decline of the Corcu Loigde and the rise of the Eoganachta.

Irish Annals entries related to the Corcu Loigde:

- M196, The first year of Lughaidh, i.e. Maccon, son of Maicniadh, in the sovereignty of Ireland. (This appears to refer to Lugaid Loigde, mentioned above as ancestor of the Corco Loigde.)

- M225, After Lughaidh, i.e. Maccon, son of Macniadh, had been thirty years in the sovereignty of Ireland, he fell by the hand of Feircis, son of Coman Eces, after he had been expelled from Teamhair Tara by Cormac, the grandson of Conn. (Lugaid Loigde was expelled from Tara.)

- FA583, The slaying of Feradach Finn son of Dui, king of Osraige... Feradach son of Dui was of the Corcu Laígde (for seven kings of the Corcu Laígde ruled Osraige, and seven kings of the Osraige took the kingship of Corcu Laígde). (An alliance between the Corcu Loigde and the Kingdom of Osraige helped the Corcu Loigde to maintain dominance in Munster.)

- For 746, Flann Foirtrea, Lord of Corco Laigde, died.

- AI815, Forbasach, king of Corcu Laígde, dies.

- AI828, The community of Corcach again collected the UíEchach and Corcu Laígde and Ciarraige Cuirche to Múscraige and they left two hundred [dead] with them again.

- U944, Cairpre son of Mael Pátraic, king of Uí, Liatháin, and Finn son of Mután, king of Corcu Laígdi, were killed by the men of Mag Féine.

- AI1103, Conchobar Ua hEtersceóil, king of Corcu Laígde, died in Ros Ailithir.

- AI1103. The son of Ua hEtersceóil, king of Corcu Laígde, went to sea with a crew of twenty-five, {and unknown is their faring or their end thereafter}. (Irish Annals)

Seventh Century: During the period of Eoganachta dominance, 7th to 10th century, the Corcu Loigde did not pay tribute to the Eoganachta kings at Cashel due to their legendary relationship to the Eoganachta through an ancient marriage. The map below offers an idea of the various tribal groups that were part of Munster around 750 CE. (Munster Region of Ireland c.a. 750) The Eoganachta were a confederation of tribes that claimed a common lineage. (Tribes and Territories of Mumhan)

Ninth Century: During the 9th and 10th centuries the Viking settlement of Cork began and grew in influence. Beginning in the 10th century the influence of the Eoganachta began to wane and that of the Dal Cais began to increase.

Tenth Century: The 10th and 11th centuries saw the rise of the Dal Cais, originally centered in southern Clare and parts of the present Counties of Kerry and Tipperary. Brian Boru, leader of the Dal Cais, became King of Munster in 978 and by 1002 he was also High King of Ireland.

Twelfth Century: In the early 12th century, 1118, Munster was divided into the Kingdom of Desmond (south Munster) and Thomond (north Munster). Desmond was ruled by the Mac Carthaigh (MacCarthy) dynasty and Thomond by the O’Briens. The area of the Corcu Loigde was in the area of Desmond.

Beginning in 1169 an Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland began, backed by Henry II of England and sanctioned by Pope Adrian IV. In 1177, Henry II divided Munster into the Earldom of Ormond and the Earldom of Desmond. However, the far southwestern portion of Desmond continued as a semi-independent Gaelic kingdom under the Mac Carthaigh clan.

Ecclesiastic History

Numerous monasteries or abbeys existed in County Cork before the arrival of the European orders and prior to the 8th or 9th century when the possible High Cross described below was likely carved. Given this fact, it is significant that there is only one possible High Cross in the county. It is possible, of course, that numerous crosses were destroyed across the years by weather and war. The early foundations of County Cork included:

Aghadown, simply noted as an early Gaelic monastery;

Ballyvourney Abbey, founded around 650 by St. Abban for the Gaelic nuns under St. Gobonate;

Bawnatemple monastery, noted as an early Gaelic foundation;

Brigown monastery, founded in the 6th century by St. Abban and probably inactive after the 10th century;

Clear Island monastery, founded by St. Ciaran of Seirkieran;

Cloyne Cathedral monastery and nunnery, founded in the 6th century by Colman mac Lenine and destroyed by the Vikings;

Coole monastery, founded by St. Abban in the 6th century;

Cork monastery, founded about 600 by St. Fibnbar;

Cullen monastery, founded by St. Laitrian for Irish nuns;

Garnish monastery, for nuns founded before 530;

Gouganebarra monastery, founded in the 6th century as a retreat for St. Finbarre who later founded Cork monastery;

Inishcarra monastery, founded by St. Senan;

Inishleena monastery, founded for monks and nuns by St. Finbarre;

Kilbeacon monastery, founded about 650 by St. Abban;

Kilcatherine, a double monastery founded by St. Caitiarn, nice of St. Senan;

Kilcrea nunnery, founded in the 6th century by St. Cere;

Kilcrumper monastery, founded by St. Abban in the 6th century;

Killaconenagh monastery, for nuns founded in the 6th century by St. Abban;

Kilmaclenine monastery, founded before 606 by St. Colman mac Leinin of Cloyne;

Kilnamanagh monastery, for women;

Kilnamarbhan monastery, founded in the 6th century by St. Abban;

Kinneigh monastery, founded by St. Colman and probably not surviving after the 10th century;

Kinsale monastery, founded by St. M’Eilte Ogh;

Labbamolaga monastery, founded in the 7th century by St. Molaga of Timoleague;

Loch-eire monastery, possibly founded by St. Finbarr;

Lough Ine monastery, a probable early site;

Nohaval monastery, reputedly founded by St. Finian;

Nohavaldaly monastery, an early monastic site;

Ross Priory, founded about 590 by St. Fachnan Mougach;

Skeam West monastery, a possible early site;

Spittle Bridge monastery, founded by Gaelic monks;

Strawhall monastery, an early site founded by St. Aed mac Brice of Killare;

Toames monastery;

Tulach-mibn-Molaga, founded in the 7th century by St. Molagga of Timoleague;

Tullylease Abbey, founded by St. Berechert, an Anglo-Saxon.

For a map that shows the location of these early monasteries and more, see (List of Monastic Houses Map) For the listing of these and other later monasteries see: (List of Monastic Houses) Most of these foundations are confirmed by the Map of Monastic Ireland. The interesting thing to note is that no foundation is mentioned by the name of Kilnaruane and none of the monasteries listed above were located in area where the Kilnaruane pillar or cross is located. This site remains a mystery.

The 12th century was marked by the reorganization or reform of the Irish Church into the Roman diocesan system. This took place at the Synod of Raith Bressasil in 1111. Cashel was established as the seat of the Archbishop. Bishops led the dioceses of Limerick Ardfert, Ross, Cork and Lismore. The area of the Corcu Loigde, in extreme southwest County Cork, was included in the diocese of Ross and of Cork. Bantry, near the one possible High Cross in County Cork, was in the diocese of Cork. In 1958 these two diocese were joined into the Diocese of Cork and Ross.

As will be noted below, the Map of Monastic Ireland lists a Franciscan monastery at Bantry. This could not have been the church/monastery around Bantry where the possible High Cross is located as the Franciscans did not arrive in Ireland until 1231. In fact the site of the Franciscan friary was within a mile of the site of the possible cross-shaft, but the two were in different locations and existed at different times.

With this background we turn to the Kilnaruane site and possible High Cross.

Bantry aka Kilnaruane

Background on the Site

Kilnaruane may have been the site of a church rather than a monastery as the Map of Monastic Ireland does not include an early monastery near Bantry. (Map of Monastic Ireland) However, The Megalithic Portal reports that there was a monastery. Tradition states that the church or monastery was founded by St. Brendan the Navigator in the 6th century. Speculation is that the church/monastery was destroyed by the Vikings in the 9th century, giving it a history of 300-400 years.

The name Kilnaruane may suggest that the church/monastery was one that adopted the Roman dating of Easter, probably following the Synod of Whitby in 664. The name can be translated as “Church of the Romans.” (Kilnaruane Pillar Stone, p. 72)

The Cross

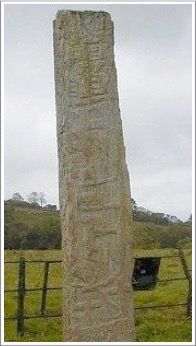

The Kilnaruane shaft is presumed to be the shaft of a High Cross. It stands about 7 feet (2.15m) in height, is 10 inches (30cm) wide and 6 inches (20cm) thick. There is carving on the two faces. A vertical groove at the top of each side may have been used to attach a ring or head. There is some speculation that this was originally a “tau” or “t” shaped cross. (Carroll, p. 1) Based on the characteristics of the cross and the carving F. Henry and P. Johnstone date the cross to the 8th century. (Johnstone, p. 277)

The East Face

The east face bears a boat that is presented vertically. See the photo to the right. Johnstone describes it as a “very fine representation of a boat with a small cross on its stern, a helmsman holding a steering oar, and four oarsmen. The boat is being rowed hard heavenwards amidst a sea of crosses.” (Johnston, p. 277)

Harbison identifies seven figures in the boat. There are four oarsmen amidships, two figures in the bow facing aft and a figure in the stern of the boat, presumably the helmsman. (Harbison, 1992, p. 132) These details are difficult to make out in detail but the photo and illustration below offer an idea of the detail of the carving. (illustration from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kilnaruane_Pillar_Stone)

Johnstone’s interest is the Bantry Boat as a boat. He points out that if the 8th century dating of the cross is accurate, the carving is pre-Viking and the boat is clearly not a Viking boat.. The shape and other characteristics of the boat make it probable it is a skin boat typical of a curragh. Johnstone notes that “no representation of a skin boat from that period is generally known.” (Johnstone p. 278) This alone makes the Kilnaruane cross shaft unique among the Irish High Crosses. Johnstone describes the carving as very realistic, writing “The attitude of the helmsman, leaning exhaustingly forward like a boat-race coxswain the angle of the steering oar, the position of the oarsmen with stroke pulling a little harder than anyone else, the bending heave of the oars, are remarkably vivid and convincing.” (Johnstone, pp. 279-280)

Although the carving is quite realistic, Johnstone also points to ambiguities. How many oarsmen are there and are they rowing or sculling? If they are rowing, there would be two oarsmen in each row and each would have one oar, operating on opposite sides of the boat. This would render a total of eight oarsmen. If they are sculling, each oarsman would have two oars, one in each hand, hence four oarsmen. Johnstone also points to a error. “The steering oar disappears where it crosses the stern. One might take that to indicate, very unusually that it was simply on the port side were it not so clear that the helmsman is holding it in his right hand.” (Johnstone, p. 280)

In addition to the boat, there are, as noted above, several crosses in the carving. There is a cross in each of the bottom corners of the panel and a cross in the upper right-hand corner of the panel. There is also a small cross on the stern of the boat.

The question of the meaning of this carving has drawn several different responses. Wallace sees it as an incident in the life of an Irish saint. Brendan the Navigator comes to mind as an example. Hourihane and Hourihane interpret it as a symbol for the ship of the church. Harbison suggests that if it is biblical in nature, it may represent Jesus Calming the Storm. (Harbison, 1992, p. 132) Based on the presence on the west face of the cross of a panel that represents Saints Anthony and Paul breaking bread in the desert (discussed below) it seems entirely possible that the image is intended as the representation of an Irish saint. Johnstone’s statement that the ship seems to be sailing toward heaven amidst a sea of crosses could be entirely consistent with this identification. The ultimate goal of the Irish saints was to find their place of resurrection and be united with God.

There are two other panels on the east face of the cross. Above the bow of the boat there is a panel containing four quadrupeds. Like the boat, this panel is arranged vertically. However, it is turned the other way round. In the panel there are two rows of beasts. In each row two of the quadrupeds face each other with their heads touching. Harbison notes that Hourihane and Hourihane interpret this panel as “Apocalyptic Beasts”, but Harbison makes no interpretation. (Harbison, 1992, p. 132)

The top panel contains a much worn carving that appears to be a double-spiral design.

The West Face

The west face of the cross shaft contains four panels in about the same space as the three on the east face. See the photo to the left. The lowest panel seems straight forward in its interpretation. It offers a classic image of Saints Anthony and Paul of the desert sharing a loaf of bread brought them by a raven. The saints sit on chairs facing each other. Between them is a table, or as Harbison points out, it could represent the tau shaped crozier of St. Anthony. Above this is a full loaf of bread and the bird that brought it. (Harbison, 1992, p. 132)

The west face of the cross shaft contains four panels in about the same space as the three on the east face. See the photo to the left. The lowest panel seems straight forward in its interpretation. It offers a classic image of Saints Anthony and Paul of the desert sharing a loaf of bread brought them by a raven. The saints sit on chairs facing each other. Between them is a table, or as Harbison points out, it could represent the tau shaped crozier of St. Anthony. Above this is a full loaf of bread and the bird that brought it. (Harbison, 1992, p. 132)

The next panel up contains an equal-armed cross as seen in the photo to the right. There is a square in the center. Each arm is rectangular and is connected to the center by a narrower rectangle.

The third panel up contains a figure that has been variously identified as a woman lamenting and simply as an orans or praying figure. The figure is best seen in a drawing in a 1913 article in the Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society pictured to the right. Indeed this illustration offers a clear image of the first three of the panels. The upper panel is described by Harbison as containing irregular animal interlace. The animal nature of this is not made clear in the illustration. (Notes and Queries p. 202)

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 67 A 2. Located south of Bantry. “The Kilnaruane or Bantry Pillar Stone is situated about a mile outside Bantry up the by-road at the West Lodge Hotel.” (Carroll, p. 1) Take the N71 south from Bantry. The cross is not visible from the road, but is signposted.

I visited this cross shaft in 2008. This was before I had discovered the National Monument Survey that could provide maps for me to most of the crosses. As was my habit, I stopped at a store and asked if anyone knew where the cross shaft was. No one did. One employ recommended that I check with the local Information Center and told me where it was located. When I arrived, this was early May, I discovered that the center had just opened for business for the season that day. The name I knew for the cross was the Bantry Cross. I had some information and a photo from the internet under this name. The attendant had never heard of it and so began an internet search of her own. While she was doing that she suggested I look over a single sheet on the counter that gave general information and illustrations of several local sites of interest. Just as she found Bantry Cross on the internet, I was seeing the cross shaft I was looking for illustrated in the very center of the page. Locals know this only as the Kilnaruane stone. She gave me directions to get there and I found the proper roads. I began looking for signpostings along the road and after several kilometers had not found one for Kilnaruane. I resolved to turn back. There was one place where there were numerous signpostings that I had surveyed along the way. I returned to this and approaching it from the east rather than the west I found the signpost for Kilnaruane. Along the gravel road it directed me to there was another signpost that directed me into a field to the right. Someone had placed a sign on the gate asking that it be closed behind me. I started up a relatively steep slope and toward the crest found the cross shaft.

Resources Cited:

Carroll, Michael J., “Antiquities of the Bantry Region”, about 1999. http://durrushistory.com/2014/08/14/antiquities-of-the-bantry-muintervara-area-west-cork-including-coomhola-borlin-colomane-and-kilnarune-stone-by-michael-carroll/

Coleman, J., “Notes and queries: Ancient carved stone near Bantry”, Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society, 1913, Vol. 19, No. 100, page(s) 201202. Published by the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society.

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Johnstone, Paul, "The Bantry Boat”, Antiquity/ Volume 38/ Issue 152/ December 1964, pp. 277-284. http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0003598X0031185

Kilnaruane Pillar Stone https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kilnaruane_Pillar_Stone

Saint Brendan’s Stone (Kilnaruane) https://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=27222