This page explores Irish High Crosses that seem to offer depictions of “The Resurrection,” ‘Christ in the Tomb,’ and/or “The Women at the Tomb.” These images are all related to the biblical stories of the resurrection. These resurrection stories are narrated in the Christian scriptures in Matthew 28:1-7; Mark 16:1-7; Luke 24:1-10 and John 20:1-9. An additional story is narrated in the Gospel of Peter, a non-canonical text, as will be explained below.

More than fifty separate figural panels on the Irish High Crosses contain images of the crucifixion. The frequency of this image is to be expected as the crucifixion is generally considered by the church to be the most important event in salvation history, symbolizing God’s act of redemption. The Cross of Muiredach at Monasterboice, County Louth, to the right, offers a fine example of a crucifixion image in the center of the head.

When it comes to the resurrection, celebrated on Easter, the most holy day in Christendom, there are a total of only ten possible images on the crosses. These can be grouped in three categories. Below, under the title of “Resurrection Scenes”, I will examine the most compelling of these images. It is found on the cross of Muiredach at Monasterboice and is visible, in the photo above left, on the right hand arm of the cross. Also included as a possible depiction of the resurrection is an image on the base of the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnoise. In addition to these images four scenes of Jesus in the Tomb include a resurrection theme. These four images will be considered below under the subject “Christ in the Tomb”. In some of these images, and four other scenes the ‘Women at the Tomb” may appear, a reminder of the Gospel message that the women were the first to visit the tomb on resurrection day. They did not find Jesus' body in the tomb because He had Risen. “The Women at the Tomb” was an early symbol for the empty tomb, and, therefore, a sign of the resurrection. Four images that may contain only this theme will be examined under the theme “The Women at the Tomb.” Three other panels that may include one or more of the women will also be noted in this category, though they will have been described under one of the other two categories.

Resurrection Scenes

The Text

None of the four gospels offer a narration of the actual resurrection. Each of the four make a jump from the burial of Jesus on Friday to the empty tomb on Sunday morning. It is the arrival of one or more of the women at the tomb that typically begins the resurrection story. However, something had taken place before their arrival. Peter Harbison, author of "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", identifies two crosses that may have an image of the resurrection. They are: Clonmacnois, Cross of the Scriptures, West face, base, lower panel, centre (County Offaly); and Monasterboice, Muiredach's Cross, West face, South Arm, (County Louth). (Harbison 1992, 288)

The Images

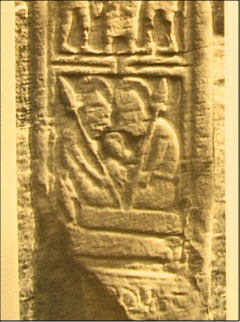

Muiredach's Cross, Monasterboice:

In this panel, seen to the left, we see two guards kneeling and facing each other. In this scene it is difficult to determine whether they are depicted as stunned and like dead men or awake. Between them there is an area with a sunken cross, a symbol of the Resurrection. The upper portion of this cross, appearing as an inverted “U”, has been interpreted as the sepulchre. Above the guards, at the top of the panel are three figures. Helen Roe, author of “Monasterboice and its Monuments” identifies all three figures as angels. In front of the central figure she sees what she describes as a “napkin in which is a soul-figure.” (Roe, 2003, p. 33) Roe believes this is a symbolic representation of the Christ spirit rising. Harbison identifies the central of the three figures as Christ with outspread knees and his arms supported by the angels on his left and right. (Harbison, 1992, p. 145) While they differ on the exact identification of the images on the upper portion of the panel, they agree that this image depicts Christ rising from the tomb.

To this description Harbison adds that there may be a third angel in the upper left-hand corner of the panel and that there is a figure behind the soldier on the left that could represent one of the women coming to the tomb on Sunday morning. (Harbison, 1992, p. 145)

Helen Roe adds a note that this is "A composition not recorded elsewhere in Irish work, offering a stylized version of the Resurrection.” (Roe, 2003, p. 33) This uniqueness makes the panel significant, though that uniqueness may be less pronounced if the next image is correctly identified.

The Scripture Cross, Clonmacnoise

The Scripture Cross also has a possible image of the Resurrection that parallels the image on the cross of Muiredach. Harbison offers only a tentative identification of this image, largely because of the deteriorated condition of the image.

This image is the central part of the lower panel on the west face of the base of the Scripture Cross. Harbison suggests the upper bodies of three human figures are visible. He describes the central figure as having outstretched arms. (Harbison 1992, p. 50) He suggests this central figure may represent Christ being raised from the tomb while the figures on each side are angels. These characteristics parallels the image on the Muiredach Cross, discussed above, however, the lower portion of the image cannot be discerned. Harbison’s question mark related to his description is warranted.

Discussion

Roe and Harbison differ in their interpretation of the image of Christ on this panel. While Roe sees Christ as a “soul figure” being drawn up on a napkin, Harbison identifies Christ as the central figure among the three heads at the top of the panel, having his knees apart and drawn up in what might be thought of as a modified yoga position. Roe's description is confusing because only three heads appear clearly in the image and the “soul figure” is not obvious unless what appears to be the chest of the risen Christ is interpreted as a head. In this respect Harbison’s interpretation is to be preferred.

What is the possible source of this image? Peter Harbison points out that a similar written description of the resurrection can be found in the Gospel of Peter. This is a non-canonical gospel believed to have been composed sometime after 150 CE. In 1886 a manuscript containing this fragmentary gospel was discovered in Upper Egypt. The script of this particular manuscript was dated to the 8th or 9th century, a century or more earlier than the production of Muiredach’s Cross. (Miller, 399) Given the close connection between Ireland and the monasticism of the Desert, it is reasonable to assume that this gospel was known in Ireland at the time of the creation of Muiredach's cross, which probably occurred in the 10th century. (Richardson and Scarry, 44)

The pertinent section of the text reads as follows: [39] “And while they were relating what they had seen, again they see three males who have come out from the sepulchre, with the two supporting the other one, and a cross following them, [40] and the head of the two reaching unto heaven, but that of the one being led out by a hand by them going beyond the heavens.” (Brown verses 39-40; also quoted in full with some differences in translation in Harbison 1992, 286)

The description from the Gospel of Peter closely parallels the tableau(s) above. Christ, supported by two [or three] angels moves up from the tomb and a cross in the tomb may be thought of as following. The possible presence of one of the women at the tomb, let's say Mary Magdalene, emphasizes that this is once more a composite image, encompassing more than one moment in time. What we see is the guards reaction to the arrival of the angels, the angels completing their part in the resurrection, and Mary Magdalene approaching the now empty tomb.

If the Gospel of Peter is the only source for this image, the soldiers would be seen to be awake and aware of what was happening. If this scene also reflects the Gospel of Matthew, the soldiers could be seen as “like dead men.” (Mt. 28:4)

Christ in the Tomb:

Christ in the Tomb:

The Text:

Each of the gospels describes the burial of Jesus. Matthew does so as follows: So Joseph [of Arimathea] took the body and wrapped it in a clean linen cloth and laid it in his own new tomb, which he had hewn in the rock. He then rolled a great stone to the door of the tomb and went away. Mary Magdalene and the other Mary were there, sitting opposite the tomb. (Mt. 27:59-61)

Only Matthew and the non-canonical Gospel of Peter discuss the guards placed at the tomb. The next day, that is, after the day of Preparation, the chief priests and the Pharisees gathered before Pilate and said. "Sir, we remember that that impostor said while he was still alive. 'After three days I will rise again.' Therefore command the tomb to be made secure until the third day; otherwise his disciples may go and steal him away, and tell the people 'He has been raised from the dead' and the last deception would be worse than the first." Pilate said to them, "You have a guard of soldiers; go, make it as secure as you can." So they went with the guard and made the tomb secure by sealing the stone. (Mt. 27:62-66) This passage explains the presence of the guards at the tomb as preventing a false claim of resurrection should the followers of Jesus take his body. As noted above, the guards are also mentioned in the Gospel of Peter. The guards will appear in each of the images below under the category of Christ in the Tomb, as they do in the Resurrection image above. They are a fixed part of the iconography.

Matthew and the non-canonical Gospel of Peter also report the coming of the angels and the reaction of the guards. And suddenly there was a great earthquake; for an angel of the Lord, descending from heaven, came and rolled back the stone and sat on it. His appearance was like lighting, and his clothing white as snow. For fear of him the guards shook and became like dead men. (Mt. 28:2-4) Like the guards, the angels also form a significant iconographic key to the identification of the scenes, though they appear in differing numbers and locations in the scenes as will be seen below.

The Images

Peter Harbison identifies four figural high crosses that contain a possible image of Christ in the Tomb. These are each discussed below. They are: the Tall Cross, Monasterboice, West 2 (County Louth); the Market Cross, Kells, East 3 (County Meath); the Scripture Cross, Clonmacnois, West 1 (County Offaly); and the Durrow Cross, West 1 (County Offaly).

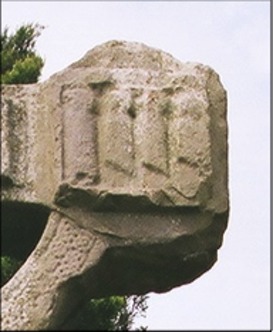

Tall Cross, Monasterboice:

This scene, pictured to the left, has some of the characteristics of the Resurrection scene discussed above on the Muiredach Cross. We see the two soldiers who are guarding the tomb holding their spears and leaning with their heads together, presumably shaken by the earthquake and the appearance of the angel described above in Mt. 28:2-4, and like dead men. Like the image on the Muiredach cross there are angels at the top of the panel above the heads of the guards. In this case there are two visible angels, although the panel has been damaged so that the entirety of the original scene is not visible. (Roe, 2003, 50) Reaching up between the guards and the angels is a cross that, as was noted above, represents the Resurrection. At the bottom of the panel we see the body of Jesus lying under a slab of stone on which the guards sit or kneel. Jesus’ head is to the left and not covered by the slab.

Harbison addresses the issue of the damage to the panel by suggesting that in its original form it probably closely resembled the scene that will be discussed below on the Cross of the Scriptures at Clonmacnoise. (Harbison, 1992, p. 149)

Market Cross, Kells:

The panel on the Market Cross at Kells, pictured to the left, is damaged and like the image on the Tall Cross at Monasterboice the description is limited to what still exists. Once again we have the body of Jesus entombed under a massive stone. In this case the head of Jesus is to the right and has been broken off. Above the slab are the two soldiers with their spears, leaning together as if dead. Between them the Resurrection cross extends upward with the head of the cross between two figures at the top of the panel. These figures have been identified as angels. To the right there appear to be two or more figures that could represent the women coming to the tomb. Though neither Roe or Harbison speculates in this case on what may have appeared in the original, unbroken, image, it is reasonable to assume that like the image on the Tall Cross at Monasterboice the original image here also paralleled that on the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois that will be considered next.

Scripture Cross, Clonmacnois:

On the Scripture Cross, pictured to the right, we have an unbroken panel that strongly resembles what we have seen on the previous two crosses. At the bottom of the panel the figure of Jesus lies beneath a massive slab of stone. His head is to the left, as is true in each example with the exception of that at Kells. In this image it is clear that there is a bird-like figure over the head of Jesus. This is a feature that may well have originally appeared on the Tall Cross at Monasterboice and the Market Cross at Kells. This bird seems to place its beak near or into Jesus mouth. This suggests that the bird may be breathing life into the dead body. There are two possible interpretations of the bird. It could represent the Holy Spirit, or it could represent a peacock. At the time the Scripture Cross was carved there was already an association with the peacock and resurrection. Some explanation may be helpful.

Father John Bartunek, LC, S.Th.D., explained the pagan origins of the connection of the peacock with resurrection in an on line article cited below. He wrote: “Peacocks often appear in early Christian art as a symbol of the Resurrection and Eternal Life. . . The most obvious [connection] is a carry-over from ancient pagan religions, some of which held the belief that the peacock’s flesh never decayed, even after it died. Early Christians, therefore, adopted the bird as a symbol of the Resurrection, Christ’s eternal, glorious existence.” (Bartunek)

In this image there is not a cross rising up between the two soldiers. There are, however three equal armed crosses on the shroud in which Jesus is wrapped. These may serve the same purpose as the crosses noted on the panels on the Tall Cross at Monasterboice and the Market Cross at Kells, representing the resurrection.

The soldiers, each holding a spear across a shoulder and with heads leaning together as if asleep or dead, fill the left two thirds of the panel. To the right of the soldiers is the figure of an angel. Located here rather than above the soldiers as in the other examples above. On either side of the spearhead on the right a head appears. Harbison has suggested these may represent two women at the tomb, as was also noted in relation to the Market Cross at Kells.

Harbison has identified a small figure in front of the angel, where two feet appear, standing on the stone that covers the grave. He states: “The identification of the small figure in front of the angel is enigmatic, but if the whole scene is related to Christ's descent into hell, it could represent Adam." (Harbison 1992, 51) In his description of the scenes related to Christ in the Tomb, Harbison quotes an extended version of the passage from the Gospel of Peter noted above related to the Muiredach Cross image described above. In suggesting that the entire scene at Clonmacnoise may relate to Christ’s descent into hell, he focuses on the last lines of that passage. They read: [41] “And they were hearing a voice from the heavens saying, 'Have you made proclamation to the fallen-asleep?' [42] And an obeisance was heard from the cross, ‘Yes.’" (Brown verses 41-42)

While Harbison may be correct in identifying a small figure in front of the angel, the identification of this figure as Adam is tenuous as the upper body of the figure is difficult to discern and may not be there at all. Is it possible that the legs on the stone slab belong to the angel and that the angel is seated? In Matthew the angel was seated on the stone that had been rolled away. (Mt. 28:2) In Mark it is noted that the angel was “sitting on the right side.” (Mk. 16:5) Only in Luke are the angels, in this case two angels, standing. (Lk. 24:4)

If Harbison’s identification of the figure of Adam in this panel is correct, it reflects a tradition that developed in the early church that Christ “Harrowed Hell.” The belief developed that between his burial and resurrection Christ brought salvation to all the righteous who had died since the beginning. This theology appears in the Apostles’ Creed, which dates to the late 4th century. The phrase there states “he descended to the dead.” The strongest scriptural support for this belief is found in 1 Peter 4:6 “For this is the reason the gospel was proclaimed even to the dead, so that, though they had been judged in the flesh as everyone is judged, they might live in the spirit as God does.” A part of this doctrine is the belief that Christ pulled Adam and Eve, as well as other leading figures in the Hebrew scriptures, from hades.

Even if Harbison is correct in identifying Adam in this scene, it does not follow that the focus of the panel is on the harrowing of hell. On the contrary, as with the other images of the resurrection and Christ in the Tomb, that do not include an image of Adam, the focus is on the moments before the resurrection of Christ and the empty tomb. If Adam is present in the scene it points once again to the composite nature of many of the scripture images on the High Crosses.

Durrow Cross:

At Durrow we have another panel that is partly broken. In this case the part of the scene that is missing is the head of Jesus. In this case his head was to the left under the slab of stone. As noted above there is a bird that seems to place its beak near or into Jesus’ mouth, suggesting the moments before the actual resurrection. The two soldiers sit on the stone slab. Each holds a spear and as in the scenes above they lean together. In this scene there is what appears to be a human figure in the space between the soldiers. Harbison offers no identification of this figure. (Harbison, 1992, 81) This figure could represent Mary Magdalene coming to the tomb. Such an identification would be in keeping with the suggestions of the presence of one or more of the women on the Muiredach Cross at Monasterboice, the Market Cross at Kells and the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnoise. Alternatively, the figure could represent an angel, whose appearance caused the guards to become like dead men. Otherwise both the angel or angels and the woman or women at the tomb are missing from this panel while one or the other or both are present in each of the other images and form a basic part of the iconography related to this event. Still, no clear identification is possible.

Discussion

There are several interesting features of these four scenes and their descriptions. First, in the images under consideration, as with the images of the resurrection above, there is no apparent attempt to show the stone that sealed the tomb. Or is there? Is it possible that the horizontal slab that mostly covers the body of Jesus is, in fact, the stone that sealed the tomb? In each of the four images in this category the stone is partly moved to the side so as to reveal Jesus’ head. Thus the tomb is depicted as partly open, no longer sealed. This would emphasize the apparently obvious reference to the moment just prior to the resurrection.

Second, in each image the body of Jesus is still in the tomb. One important element of the Christian belief in the resurrection is the empty tomb. In that sense, these are all pre-resurrection depictions.

Third, the slender cross in the image appears only at Monasterboice and Kells, though three crosses mark the shroud at Clonmacnoise. No cross is present at Durrow or Clonmacnoise. Helen Roe is probably correct in identifying these as "resurrection crosses". She sees this as a graphic reference to the passage from the Gospel of Peter quoted above in connection with the resurrection scene on Muiredach's Cross at Monasterboice. (Roe, 1988, 28) This is, of course at odds with the presence of the body in the tomb. This apparent contradiction likely offers another reminder that many of the scenes are composite. They depict more than one moment in time.

Fourth, it is likely that the missing material on the crosses at Monasterboice and Kells contained the figure of a bird, similar to the images at Clonmacnois and Durrow. Harbison writes, "Francoise Henry pertinently alluded to the comparison of birds breathing life into the mouths of those arising on the Day of Judgment on a 9th/10th century ivory in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, so that the bird on the High Cross panels may be taken to be (? The Holy Spirit) breathing life into the shrouded body of Christ in the tomb on Easter morning." (Harbison, 1992, 286-7) Alternatively, as suggested above, if the bird is a peacock, the association with resurrection is established in a different way. Either way, the presence of the bird establishes a connection between this scene and the resurrection. Thus the image transcends Jesus buried and points to the empty tomb.

The Women at the Tomb

The Texts:

In Mark, the earliest of the Gospels, the women arrive at the tomb wondering who will roll the stone away and find that it is already removed. “And entering the tomb, they saw a young man sitting on the right side, dressed in a white robe; and they were amazed.” (Mk. 16:5) The young man announces that Jesus is risen and that his body is no longer in the tomb. The reader or hearer of the text is left to assume that young man is an angel.

In Matthew as Mary Magdalene and the other Mary arrive, “there was a great earthquake: for an angel of the Lord descended from heaven and came and rolled back the stone, and sat upon it. His appearance was like lightning, and his raiment white as snow. And for fear of him the guards trembled and became like dead men.” (Mt. 28:2-4) When the angel speaks to the women, the body is already gone. The angel says “I know that you seek Jesus who was crucified. He is not here: for he has risen.” (Mt. 28:5b-6a)

In Luke the women who come to the tomb are not named till the end of the passage (Lk. 24:10) but their presence is announced in Lk 24:1. When they arrived “They found the stone rolled away from the tomb, but when they went in, they did not find the body. While they were perplexed about this, suddenly two men in dazzling clothes stood beside them.” (Lk. 24:2-4)

In the Gospel of John Mary Magdalene arrives at the tomb alone. “Early on the first day of the week, while it was still dark, Mary Magdalene came to the tomb and saw that the stone had been removed from the tomb.” (John 20:1) She then goes to tell Peter and John, who run to the tomb. Only after the men have left again does Mary encounter, not an angel, but the risen Christ himself.

The Gospel of Peter, referred to several times above, also has Mary Magdalene and her friends coming to the tomb early own Sunday morning. 50] Now at the dawn of the Lord's Day Mary Magdalene, a female disciple of the Lord (who, afraid because of the Jews since they were inflamed with anger, had not done at the tomb of the Lord what women were accustomed to do for the dead beloved by them), [51] having taken with her women friends, came to the tomb where he had been placed. (Gospel of Peter 50-51) As in the canonical Gospels they find the stone rolled away and the tomb empty. They are informed by “a certain young man seated in the middle of the sepulcher, comely and clothed with a splendid robe,” that Jesus is not there but has risen. Gospel of Peter 55b)

The Images

We have already seen seen several possible examples of the Women at the Tomb. Those on Muiredach’s Cross at Monasterboice, the Market Cross at Kells and the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnoise are noted again below.

Muiredach’s Cross, Monasterboice

Peter Harbison suggested that one of the figures on the scene of the resurrection on Muiredach's Cross at Monasterboice may be a woman who came to the tomb on Sunday morning. (Harbison, 1992, 145)

Market Cross, Kells

On the Market Cross at Kells, Helen Roe suggests some figures in the upper right-hand corner of the image potentially represent two or more women who came to the tomb. (Roe, 1988, 28)

Scripture Cross, Clonmacnoise

Peter Harbison puts forward the possibility that a collection of heads in the upper right-hand corner of the scene on the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois may be women at the tomb. (Harbison, 1992, 51)

There are four other images that can be identified as the “Women at the Tomb.” These include: Carndonagh, East 1, (County Donegal); Clonmacnois, Cross of the Scriptures, West face, Base, Lower panel, Right (County Offaly); Kells, Unfinished Cross, East face, North arm (County Meath); and Monasterboice, Tall Cross, West 3 (County Louth).

Carndonagh Cross

On the east shaft of this cross is an image of the crucifixion. The appearance of this image on the shaft of a cross is rare. Below this we see three figures, dressed in long robes, facing to the left. Harbison has identified this as a possible rendering of the women coming to the tomb. However, in context, the image would more likely represent the women at the crucifixion rather than at the empty tomb.

There is certainly scriptural evidence for the fact that there were women present and observing the crucifixion of Jesus. In Matthew it is stated that “There were also many women there, looking on from afar, who had followed Jesus from Galilee, ministering to him; among whom were Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James and Joseph, and the mother of the sons of Zebedee.” (Mt. 23:55-56) Thus, there are three specific women named. In Mark a large number of women is also mentioned. Three specific women are named here as well. They are Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James the younger and of Joses, and Salome. (Mk. 15:40) While the names are not identical to those in Matthew, the number three is consistent. Luke does not mention any specific names, noting only that “all his acquaintances and the women who had followed him from Galilee stood at and distance and saw these things.” (Lk. 23:49) The Gospel of John returns to the theme of three named women. In this case they are Mary the mother of Jesus, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene. The Gospel of Peter names Mary Magdalene and adds her “friends.” While the names differ from gospel to gospel three women are named, in several of the Gospels, as coming to the tomb.

While this image is included here because of Harbison’s identification, it is not likely to represent the Women at the Tomb, being rather a representation of the Women at the Crucifixion.

Scripture Cross at Clonmacnoise

As is true above where the panel on the lower half of the west base is considered as containing an image of the Resurrection, only a brief comment will be made here. On the lower portion of the base, on the right-hand side of the panel, Harbison has suggested there may be an image of two people approaching a seated figure that has a hand out in greeting. Harbison acknowledges no previous interpretation of the entire panel had been offered. This portion of the base is badly worn, hence the difficulty in interpretation. As noted above, none of the Gospels mentions two women coming to the tomb, so the number is unusual. However, two women at the tomb parallels the number of possible women depicted in the Market Cross at Kells, the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnoise, and the Durrow Cross. Based on this, Harbison’s identification may be accurate.

Kells, Unfinished Cross:

There has been little speculation about the content of this scene, pictured to the left. Helen Roe describes the tableau as follows: "On the east side of the head, the panel on the north arm shows a row of four persons, dressed in long robes with hoods (?) over their heads, all of them facing in towards the Crucifixion; but, damaged as well as unfinished, the subject cannot be recognized.." (Roe, 1988, 55) Peter Harbison is willing to take a guess at the subject matter of this scene, and interprets the carving differently from Roe. "The partially-finished panel on the north arm consists of four figures -- that on the left, clothed to the ankles, seeming to face the other three approaching from the right, who are all seemingly dressed in similar cut-away cloaks. Although there are no distinguishing attributes or gestures visible, the best interpretation of this panel is probably that of the angel on the left speaking to the three women as they approach the tomb after the resurrection." (Harbison, 1992, 112) Harbison and Roe differ in their interpretation of the direction in which the figure on the left is facing. This difference has influenced the identification of the scene. If all four figures face the same direction, it is still possible that the women at the tomb are suggested. However, only the Gospel of Luke leaves open the possibility that more than three women went to the tomb. Luke 24:10 reads “Now it was Mary Magdalene and Joanna and Mary the mother of James and the other women with them who told this to the apostles.” If the left-hand figure faces the other three, Harbison’s suggestion makes sense and conforms to the description of the event in the Gospel of Mark. There it is Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James and Salome who bring spices to anoint the body of Jesus. There we read: “And entering the tomb, they saw a young man sitting on the right side [of the tomb], dressed in a white robe.” (Mark 16:5a) The disparity here, and in the case of the Gospel of Matthew, is that the angel is described as sitting rather than standing. A simple compositional decision could account for the left-hand figure standing and is not a serious impediment to Harbison’s identification. It would certainly be helpful in confirming an identification if the carvings planned for the opposite arm and the top arm were known.

Monasterboice, Tall Cross:

As in the case of the Unfinished Cross at Kells, there is difference of opinion about the proper identification of the tableau on the Tall Cross, pictured to the right. Harbison lists a number of interpretations and the scholars who have supported each. These explanations include: The Transfiguration; three of the Apostles; Peter, James and John; and the Journey to Emmaus. For example, Helen Roe writes of this scene as follows: "Three persons standing frontally each holding a book. Possibly three of the apostles." (Roe, 2003, 50) Peter Harbison offers the following analysis. "Three long-robed figures, shown frontally, each of them holding up an object in front. As the central and left-hand figures seem to hold cup-like vessels, the scene probably represents the Three Holy Women at the Tomb bringing spices, and although the object held by the right-hand figure might seem like a book, it could also be understood as a box-like container." (Harbison, 1992, 150)

Discussion

The gospels do not agree on which women went to the tomb early Sunday morning. See above for an assessment of the way each of the Gospels describe the woman or women who came. Whatever their number, symbolically the women at the tomb have become a sign of the resurrection.

At Kells the figure on the left is dressed differently than the three figures on the right and faces them. This would tend to suggest that the three figures dressed alike have a shared identity while the other figure has a different and separate identity. Which way the figure on the left is facing (toward or away from the crucifixion) is not completely clear. Both the head and the feet could be seen to face either in toward the crucifixion or away from it. Given the fact that the carving on the opposite arm of the cross had not been started and that the upper arm of the cross is missing, it is difficult, as Helen Roe suggests, to make a certain interpretation. There is a lack of context. Nevertheless, Harbison’s suggestion of the women greeted by an angel is an attractive option.

The situation with the tableau on the Tall Cross is equally as complex. Given the various interpretations of the scene and that Peter Harbison is the only one to identify it as the women at the tomb, his suggestion must be taken with a grain of salt. In context, the image appears above an image often identified as the Baptism of Jesus. Even this is unclear, however, as Francoise Henry identifies it not as the baptism but as the women at the tomb and Helen Roe identifies it as the resurrection of the dead. (Harbison, 1992, 149-50) At the bottom of the shaft on this side is the figure of Christ in the tomb discussed above. Above that image is the figure that has been identified as the women at the tomb, the resurrection of the dead, and the baptism of Jesus. The later identification, made by Harbison is almost certainly the correct one. Next we have the image with the three figures that is under consideration here. Above that, the next two panels have also been interpreted in a number of ways. Harbison identifies them as the Traditio Clavium below and the Raised Christ (?) above. Taking Harbison’s other identification, as noted above, his identification of the panel under consideration as The Women at the Tomb makes sense, though it is not conclusive.

The possible examples of the Women at the Tomb are all speculative. The gospels do, however all mention one or more of the women being at the tomb on Sunday morning. Particularly in the scenes of Jesus in the tomb and the resurrection, it would not be out of place at all to show one or more of the women. They were, after all, an important part of the story. It may be that Peter Harbison is correct in interpreting the images at Kells and Monasterboice as the women at the tomb, but as we have seen there are other explanations that cannot be easily dismissed. As with many of the scenes on the figural crosses, numerous interpretations are possible.

Conclusions

Images on the Irish High Crosses related to the resurrection fall into three categories. The case for each of these three types of images being related to the single event of the resurrection is strong. At the same time, the body of Jesus in the Tomb on four of these images suggests a pre-resurrection moment while The Resurrection images and the Women at the Tomb images each affirm an already empty tomb.

The first category, The Resurrection images, attempt to capture the moment in which Christ is raised from the tomb into the sky. There are at most two examples of this. The images of the Resurrection seem to be visual expressions of the text found in the non-canonical Gospel of Peter. The image of Christ being raised and the fact the guards heads are not leaning together point to this conclusion. The Christ in the Tomb images, with the heads of the guards leaning together tend to reflect the narrative in the Gospel of Matthew where the guards are stunned by the appearance of the angel(s) and become like dead men.

The second category pictures Christ in the Tomb. There are four examples of this. These images are interpreted as related to the resurrection because in at least two of them, and probably in all four, a bird can be discerned that is presumably about to breath life into the body of Jesus. In addition, I have suggested that the slab above Jesus’ body may represent the stone partly moved away. Thus, these images represent the moment(s) just prior to the resurrection.

The third category includes images that may picture the Women at the Tomb. These images are related to the Resurrection because the women who arrive at the tomb find it empty. They are, therefore indicators of the Resurrection. The Women at the Tomb images include examples from all three categories. The Muiredach Cross at Monasterboice, one of The Resurrection scenes, includes a possible woman at the tomb. The Market Cross at Kells and the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnoise, two of the Christ in the Tomb scenes, also include possible women at the tomb. Women at the tomb also, obviously, appear on all the images under the heading Women at the Tomb. These include: the Cardonagh Cross, the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnoise, the Unfinished Cross at Kells and the Tall Cross at Monasterboice. The possible images of the Women at the Tomb all rely on conjecture and can be interpreted in other ways, depending on the context in which they occur.

References cited:

Bartunek, John, Why are Peacocks Considered Symbols of the Resurrection? https://catholicexchange.com/peacocks-considered-symbols-resurrection. April 24, 2017.

Brown, Raymond, translator, The Gospel of Peter, http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/gospelpeter-brown.html

Harbison, Peter, The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey, Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Miller, Robert J. ed., The Complete Gospels: Annotated Scholars Version, Harper Collins, 1992.

Richardson, Hilary and Scarry, John, An Introduction to Irish High Crosses, Mercier Press, 1990.

Roe, Helen M., The High Crosses of Kells, Meath Archaeological and Historical Society, 1988.

Roe, Helen M., Monasterboice and its Monuments, County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society, 2003.