Historical Background

County Meath takes its name from the historic Kingdom of Meath, which derives from Midhe meaning "middle" or “centre". The map to the right, found at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Meath, shows the Kingdom of Mide in about 900 CE. Western County Meath as well as Westmeath and parts of north Offaly and south Longford were included.

Pre-History

There is evidence for human habitation in the present County Meath during the Mesolithic period (8000-4000 BCE). These folk were hunter gatherers. The first farmers arrived about 4000 BCE. Their presence is attested to by the presence of Court Cairns and signs of huts as at Rathkenny, northwest of Slane. By 3500-3000 BCE the construction of Passage Tombs began, illustrated by tombs at Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth. About 2000 BCE the Beaker people or culture arrived. Their distinctive pottery was found in single person graves. This was also the period of the copper and bronze age in Ireland (2500-500 BCE). The Iron Age (500 BCE-400 CE) also brought the arrival of the Celts and the first appearance of La Tene style art. The Iron Age also saw the transition from Pre-history to the Historic period of Irish history.

The Iron Age

Ptolemy’s map of Ireland, produced about 150 CE offers the names of some of the early tribes of Iron Age Ireland. Tribes that are indicated for the area that is now County Meath include the Blanii and Eblani. Apart from Ptolemy’s naming these tribes, little is known of them.

By about 300, part of the Voluntii area was known as Breagh. Breagh (Brega, Breaga) was the site of Tara (Temuir), the ancient capital of Ireland. Prior to 500 CE, the area of Breagh was part of Leinster. About 500 the Southern Ui Neill began the process of taking Brega from Leinster. (Charles Edwards p. 156) Tara, associated with the High King of Ireland, was then ruled by the Southern Ui Neill with the High Kingship alternating between the Southern Ui Neill and the Northern Ui Neill of Aileach (County Donegal). Breagh included the southern part of what is now County Louth. The ancient home to the kings of the sub-kingdom of Brega was at Knowth.

The Southern Ui Neill were descendants of Fiacha, son of Niall of the Nine Hostages. Beginning in the 5th century they were expanding into what would become Mide, the “middle kingdom.” At its most extensive Mide included Counties Meath, Westmeath, and parts of Cavan, Louth, northern Dublin, Kildare and Offaly.

During the 8th centuries both Mide and Brega were expanding at the expense of the Kingdom of Ulster. (O Croinin, p. 221)

By the 12th century Mide and Brega were contracting in size because of incursions in the north by the kingdoms of Breifne and Fernmag and expansion in the south by Leinster. (O Croinin, p. 925) During this time the O’Carroll Kingdom of Airgialla (Oriel) expanded into the north of what is now County Louth. The O’Carrolls (O’ Cearbhail) Kingdom of Airgialla was divided following the death of King Murchadh in 1189, as a result of the growing strength of the English in Ireland. “The coastal plain between Drogheda and Dundalk, which became known as Louth or Uriel, was rapidly colonized.” (Foster, p. 56)

Ecclesiastic History

Christianity arrived in Ireland and in what is now County Meath in the 5th century. St. Patrick was active in what is now County Meath. This is demonstrated by the number of churches that he founded, some of which became monasteries. The list below, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_monastic_houses_in_County_Meath, lists eight churches that became monasteries as being founded or possibly founded by St. Patrick. The monasteries listed below include only the early monasteries. Of the 54 monasteries listed below, only four have high crosses or high cross fragments. However, there are several sites with high crosses that are not included in the list below. They include: Balsitric, Castlekieran, Girley/Fordstown, Killary, Knock and Nobber.

Ardbraccan Monastery, early site

Ardsallagh Monastery, early site

Argetbor Monastery, early site, Patrician monks

Castledeeran Monastery, early site, founded 8th century by St. Ciaran

Clonard Abbey, early site, founded c.520 by St. Finnian

Clonguffin Monastery, early site, nuns, founded before 760 by St. Fintana?

Collumbus Monastery, early site, possibly in Meath

Dal Bronig Monastery, early site, founded 5th century

Disert-moholmoc Monastery, early site, possibly in Meath

Diore-mac-Aidmecain Monastery, early site, nuns, founded 6th century

Donacarney Monastery, nuns

Donaghmore Monastery, early site, founded 5th century by St. Patrick for Cruimthir Cassan (St. Cassanus)

Donaghpatrick Monastery, early site, founded 5th century by St. Patrick

Donaghseery Monastery, early site, founded 5th century

Druim-corcortri Monastery, early site, founded 5th century by St. Patrick for Diarmait

Druimfinchoil Monastery, early site, founded by Columb and Lugad

Druimmacubla Monastery, early site, founded 5th century

Dulane Monastery, early site, founded 5th century?

Duleek Monastery, early site, founded before 489 by St. Ciarnan

Dunshaughlin Monastery, early site, founded 5th century by Senchall (St. Secundus)

Emlagh Monastery, early site, probably founded by a St. Beccan (not Beccan of Cluiain-ard)

Feart-Cearbain Monastery, early site

Fennor Monastery, early site, founded by St. Nectan?

Indeidnen Monastery, early site, founded before 849

Inishmot Monastery, early site, founded 6th century by St. Mochta

Kells Monastery, early site, possibly founded 6th century by St. Colmcille

Kilbrew Monastery, early site, founded 7th century

Kildalkey Monastery, early site, founded by St. Mo-Luog

Kilglin Monastery, early site, founded 5th century by St. Patrick

Killabban Monastery, early site, founded 6th century by St. Abban

Killaine Monastery, early site, nuns, founded by St. Enda for his sister Fanchea

Killalga Monastery, early site, possibly in Co. Meath

Kilmoon Monastery, early site, founded 6th century?

Kilshine Monastery, early site, nuns, founded before 597? by St. Abban for St. Segnich (Sinchea)

Kilskeer Monastery, early site, monks and nuns, founded 6th century

Leckno Monastery, early site, founded by 750

Lough Sheelin Monastery, early site, founded 6th century? by St. Carthag

Mornington Monastery, early site, founded 6th century by St. Colmcille

Navan Monastery, early site, founded 6th century

Odder Priory, possible early site, nuns

Oristown Monastery, early site, founded by St. Finbar or Cork

Piercetown Monastery, early site

Rathaige Monastery, early site, possibly in Co. Meath

Rath-becain Monastery, early site, founded by St. Abban, possibly in Co. Meath

Rathossain Monastery, early site, founded 686 by St. Ossain

Russagh Monastery, early site, founded by St. Caeman (Coeman) Brec

Screen Monastery, early site, founded before late 9th century

Slane Monastery, early site, founded by St. Patrick

Staholmog Monastery, early site, founded 6th century by St. Colman

Tara Monastery, early site, founded before 504, possibly by St. Patrick for Cerpan

Teltown Monastery, early site, founded before 723

Trevet Monastery, early site, founded before 563, probably by St. Columcille

Trim Abbey, early site, founded 5th century by St. Patrick

Tullyard Monastery, early site

In addition to St. Patrick, “The presence of the monastic family of Colmcille is well attested to in Meath.’ Clonard, “the training place of saints”, founded by St. Finian, seems to have been one of the seed beds of the Irish monastic tradition that transformed the structure, inherited from the Roman Church, with its emphasis on bishops ruling territorial units called dioceses, and exercising both, pastoral and judicial responsibilities. By the end of the sixth century, Meath was covered with monasteries which ruled the Church through their abbots, often members of the ruling families of the tribe from which their founder had come. The abbots in time were very often married and rulers of Christian communities which were made up of married monks, celibate monks and nuns, and the so called manaig attached to the monasteries who worked the land, and were the tradesmen of the monasteries. In short, the monasteries were Christian communities which included, what we today would regard, as people who were members of religious orders.” (http://www.navanhistory.ie/index.php?page=navan-and-meath-2)

One of the early founders of monasteries in Ireland was St. Finnian of Clonard. As noted above, he founded the monastery at Clonard, in County Meath about 520. This corresponds to the time when the Southern Ui Neill were expanding into Mide and Brega. St. Ciaran of Clonmacnoise and St. Columcille of Iona studied with Finnian. Clonmacnoise, in County Offaly became a powerful monastery with wide ranging influence. St. Columcille founded numerous monasteries including Derry (County Derry), Durrow (County Offaly), Kells (County Meath) and Swords (County Dublin). These Columban churches were also influential. The great churches such as Armagh, associated with St. Patrick; Clonmacnoise, associated with St. Ciaran; Clonard, associated with St. Finnian; Kildare, associated with St. Brigid and the Columban monasteries, associated with St. Columcille, struggled with each other for influence. Charles Edwards has noted that “The kings of Meath in the eighth century avoided committing themselves to any one great church. Although they favored Durrow, one of Columba’s monasteries, and probably gave the land for the foundation of Kells, another Columban monastery, early in the ninth century, they also promoted Clonard and patronized Clonmacnois.” (Charles Edwards, p. 26)

After 1100 European orders entered Ireland. These included Carmelite Friars, Augustinian Canons Regular and Cistercians. The beginning of the 12th century also saw the churches and monasteries in Ireland brought into conformity with Roman church structure. “One of the first great initiators of reform in Ireland was Maol Muire Ua Dunain, papal legate at the synod of Cashel in 1101, and the first bishop of Meath. He got a handsome epitaph in one of the annals when he died in 1117 being styled “chief bishop of Eirinn, head of learning and devotion of the west of the world”. At Rathbreasail in 1111 two territorial dioceses were set up in the Kingdom of Meath, one at Duleek for the east of Meath, and one at Clonard for the west. At Uisneach another synod divided Meath into Clonard for the east, and Clonmacnoise for the west. Finally at Kells in 1152 a great synod presided over by Cardinal Paparo, the legate sent to represent Pope Eugene IV, set up the dioceses of Clonard and Kells. In time Kells was absorbed into Meath [which Clonard was soon called] when its last bishop died in 1211. Today the Bishopric of Meath, stretching from the Shannon to the sea, reflects the boundaries of the old kingdom of Meath which disappeared at the Norman Conquest.”

The High Crosses

The high crosses of County Meath include: Balsitric; Castlekieran North, South, West and base; Colp cross and base; Dulane; Duleek North and South; Girley/Fordstown; Kells East, Market, South or Unfinished, West or Broken, and decorated base; Killary cross-shaft and base, cross-head and base fragments and cross-shaft fragments; Knock; Nobber base and crosses 1 and 2; and Fennor or Slanecastle.

Balsitric Cross

There is no information regarding the history of this site. The presence of the church site, where the cross-head was found, was identified by an aerial photograph as having a low earthen bank.

The cross-head was located during the ploughing in a field near the field known as “the Church field.” It is in the possession of the National Museum of Ireland. (Balsitric Church)

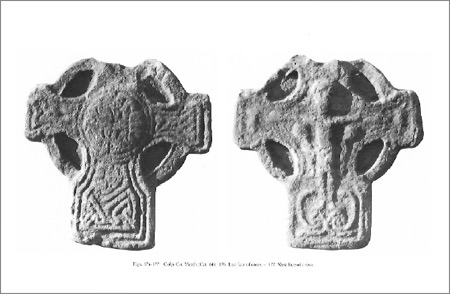

Balsitric ME006-033001- The head of a cross with an imperforate ring. The cross-head measures 11.25 inches (28.6 cm) in height by 11 inches (28 cm) across the arms. The fragment is about 2 inches (5 cm) thick. The cross was found in the ploughing of a field known as “the Church field”. It was located within the old ecclesiastical enclosure. (Michael Moore, Historic Environment Viewer)

Face 1: On the face pictured to the left below there is the shape of an equal armed cross and there is a low boss in the center of the head.

Face 2: On the face pictured to the right below there is a crucifixion scene. The arms of Jesus are angled down. Harbison notes that there may be a boss on each arm and there could also be something above Jesus’ head. (Harbison, 1992, p. 25)

Sources Consulted

Balsitric Church: http://www.meathheritage.com/index.php/archives/item/me00261-balsitric-church.

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Historic Environment Viewer: http://webgis.archaeology.ie/historicenvironment/; County Meath, High Cross, Balsitric.

Castlekieran

This essay includes an Introduction to the Site, a description of each of the Crosses located there and other features on the site, including a cross base, a cross slab, and an Ogham stone. I've also included a personal story about Getting There. The photo below of the South Cross shows that the interior of the enclosure was heavily overgrown when my wife and I visited. (photo 2011)

Introduction to the Site

Castlekieran was known in ancient times as Bealaigh-duin or “the Road or Pass of the Fort.” In early Medieval times there were a number of raths or cashels in the area. A monastery was founded here by Saint Ciaran which became know as Diseart Chiarain-Bealaigh-duin, “Ciaran’s desert at the Road of the Fort.” (Cogan, pp. 124-5) There are several Irish saints with the name of Ciaran (Kieran). St. Kieran of Disert-Kieran, Co. Meath, was referred to by the Irish Annals as "Kieran the Devout". He wrote a "Life of St. Patrick." (New Advent, Kieran) The monastery he founded is mentioned several times in the Annals of the Four Masters.

770: Ciaran, the Pious, of Bealach-duin, died on the 14th of June.

855: Siadhal of Chiarainl (died)

868: Comsudh, Abbot of Disert-Chiarain, of Bealach-duin, scribe and bishop, died.

949: Godfrey, son of Sitric, with the foreigners of Ath-cliath, plundered Ceanannus, Domhnach-Padraig, Ard-Breacain, Tulan, Disert-Chiarain, Cill-Scire, and other churches of Meath in like manner; but it was out of Ceanannus they were all plundered. They carried upwards of three thousand persons with them into captivity, besides gold, silver, raiment, and various wealth and goods of every description.

961: Dubhthach of Disert-Chiarain (died); Caencomhrac, son of Curan, distinguished Bishop and Abbot of Cluain-Eois.

1170: An army was led by Mac Murchadha and his knights into Meath and Breifne; and they plundered Cluain-Iraird, and burned Ceanannus, Cill-Tailltean, Dubhadh, Slaine, Tuilen, Cill-Scire, and Disert-Chiarain; and they afterwards made a predatory incursion into Tir-Briuin, and carried off many prisoners and cows to their camp. (Annals of the Four Masters)

The High Crosses:

There are three High Crosses in the Castlekieran enclosure. In addition, there is the base of a fourth cross. The base was placed by the chapel in recent years. It had been in the River Blackwater that runs along the northeast edge of the monastic site. The three crosses are located respectively to the north, south and west of the small chapel on the site. They are sometimes referred to as "termon" crosses. This term refers to church lands and derives from the Latin terminus meaning boundary. (Merriam-Webster) Thus termon crosses marked the sanctissimus or most holy area of the monastery, i.e. the area around the church. (for more on the sanctissimus and other zones of a monastic site, see Management Plan for Clonmacnois p. 14) "The monks were aware that stone crosses or cross-inscribed slabs could fill the same functions as walls; the sacred space need not be hidden, but merely marked out and enclosed. The famous carved crosses of early Ireland could set the limits of a settlement, just as they marked roads and the sacred places along them. . . . Sometimes, as at Castle Kieran and Ferna Mor, crosses circled the inside of the enclosure, doubling the security of physical walls." (Bitel, p. 64)

Each of the Castlekieran crosses is sandstone. All three crosses have roll mouldings along the edges. The south and north crosses also have cylindrical shaped abutments in the armpits of the cross. (Harbison, 1992, p. 41) On some crosses, such as the Scripture Cross at Clonmacnois, these cylinders are on the ring and point toward the armpits. (See High Crosses: An Introduction above)

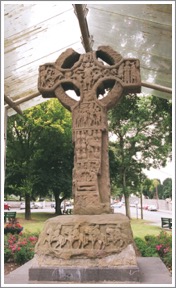

The South Cross:

The photos above show the South Cross. On the left is the west face of the cross, and on the right is the east face.

Peter Harbison describes the South Cross as follows: "the South Cross is 9’9” (2.97m) high and 4’3” (1.30m) across the arms. The shaft is 19” (49cm) wide and 14.5” (37cm) thick. It stands on a base about 35” (90cm) high and which measures 50” (1.27m) by 34” (87cm) at ground level. In the centre of the head of the east face there is a rounded setting bearing a boss with interlacing. The end of the north arm has a panel of loose interlace, and there is a further panel of interlace on the lower left segment of the ring. The remainder of the cross is undecorated." (Harbison, 1992, p. 42)

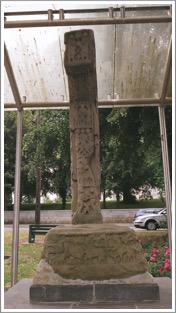

The North Cross:

The photos above show the North Cross. On the left is the west face and on the right is the east face.

Harbison writes "the North Cross as 8’7” (2.62m) high, 43” (1.10m) across the arms, the bottom of the shaft is 21” (53cm) wide and 18.5” (47cm) thick. It stands on a base which is 29.5” (75cm) high, and measuring 41” (1.04m) by 39” (1m) at ground level. The arms are tilted slightly upwards. The ends of the arms are decorated with interlace [visible in the photo above on the right]. On the east face the lower left segment of the ring is decorated with interlace, while the upper left and lower right segments have a 'battlemented' design which is also found on the ring on the west face." (Harbison, 1992, pp. 41-2)

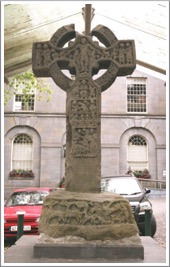

The West Cross:

The photos above show the West Cross. The photo on the left shows the east face. The photo on the right is the north face.

The West Cross is described as follows: "The West Cross is 6’10” (2.08m) high. The southern arm has been broken away, but the head would have originally measured about 33.5” (85cm) across the arms. The shaft is approximately 14.5” (37cm) wide and 9.5” (24cm) thick at the bottom. The cross stands on a slightly stepped base without mouldings; it stands to a height of about 22” (56cm) and measures 36” (91cm) by 29.5” (75cm) at ground level. The cross is undecorated, but -- unlike the other two crosses on the site -- the plinth at the bottom of the shaft is broader than the shaft itself." (Harbison 1992, p 42)

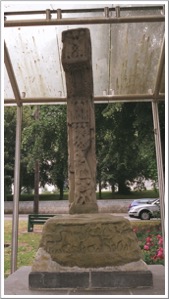

The Cross Base:

The base of a fourth cross is now located near the ruins of the old church. In the mid-nineteenth century W.R. Wilde reported two legends regarding this base and its cross.

Wilde identifies what could now be considered the east cross as the "northern one." He writes that it "was erected in a ford in the river, a very remarkable situation for one of these early Christian structures. The base still stands in its original locality, but the shaft, the arms, and the top were removed, it is said, many years ago, by some good Protestant, who, anxious to show his loyalty, as well as his detestation of such idolatrous structures, threw them into into an adjoining deep pool in the river." (Wilde, p. 138)

The second legend involves Saint Columcille. "The old tradition current among the people here concerning these crosses is, that St. Kieran had a number of them hewn at the quarry of Carrickleck, and brought here to adorn his church. They were the wonder, the admiration, and—alas ! that such a sentiment should enter into the breast of Christian saints—the envy also of all the neighbouring saints and church builders. St. Columb, who was then erecting his church and tower at Kells, cast, it is said, a longing eye upon St, Kieran's crosses: he came by night and surreptitiously abstracted at least three of these, which the traditionary legend says are those now remaining at Kells, At last, upon the night that he was taking away the fourth, St, Kieran awoke, and caught him in this very act of petty larceny, Kieran immediately 'buckled' in his brother of Kells, just as he was stepping into the ford of the river with the base of the cross on his back; but the latter being the younger and the stronger man, the cross-owner was soon worsted. He wasn't, however, to be beat so easily, so he still held fast by the thief, who, seeing that he could not get off clear with his booty, threw it into the middle of the river, from which it has never since been removed, and where, except during a heavy flood, it is always to be seen." (Wilde, p. 139)

Wilde goes on to debunk at least the second of the legends. He points out that Saint Kieran is reported by the Annals to have died in 770, a considerable length of time after the death of Columcille. (Wilde p. 140) Whether this base and its cross were originally erected in the river at a ford is unknown.

The Cross Slab:

The image above is a rough tracing of a sketch of the Castlekieran Cross-Slab produced by De Noyer in 1865 and found in O'Connell p. 167. It offers a clearer sense of the image found on the Cross-Slab itself as pictured to the right.

O'Connell describes the cross-slab as follows: "It measures approximately 48” (1.2m) in height by 24” (61cm) in width, and the average thickness is about 3” (8cm). . . . The cross is deeply incised in double lines and displays cup-shaped terminals. It is enclosed by an incised quadrangle. There is no inscription." (O'Connell, pp. 167-168) When O'Connell viewed the cross-slab it was leaning against a tombstone. It has been moved to the church where it is suspended on the north wall.

The Ogham Stone:

Ogham is a form of writing used in Early Medieval Ireland to write what has been referred to as Old Irish. It is sometimes known as the “Celtic Tree Alphabet” as each letter seems to be ascribed to a species of tree. Most of the inscriptions contain personal names. The extant examples of Ogham are all on stone. Other substances were certainly carved with Ogham, especially wood.

The inscription on the Ogham stone at Castlekieran (illustrated to the left) has been translated into Latin as “COVAGNI MAQI MUCOI LUGUNI” (SOCOIN/TOBI, p. 51) This translates to “Covagni, son of the tribe of Luguni”

The stone is mounted on a shelf on the northwest corner of the church at Castlekieran.

The Church:

Writing in 1850, W.R. Wilde had this to say about the church at Castlekieran. "Its direction is, as usual, east and west. No doorway or window-case remains, to indicate by their style the period to which the church might be referred; but judging from the masonry, which consists of small stones and rubble-work set in an unusually great quantity of mortar, we should consider it an erection of a period not earlier than the fourteenth century." (Wilde, p. 141)

A little over a decade later, in 1862, Rev. A. Cogan, Catholic Curate of Navan described the church as follows: "The old church is quadrangular, measuring 45.5’ (13.86m) by 20’ (6.1m). Most of the stones have been carried away, and the whole presents a melancholy picture of desolation." (Cogan, p. 125)

The church is indeed desolate. The entire graveyard is covered by tall grass. This growth is especially heavy on the east side of the church.

Saint Kieran's Well:

Kieran’s Well is located near the old monastic site of Castlekieran, not far to the west. The origin of the spring is near the top of a steep hill and the site is adjacent to the road. It flows down through stone that the water carved over the years forming a stream at the lower end of the site. Tradition suggests the water has curative powers, especially for tooth-aches and headaches.

"There was a big whitethorn bush over the well and long ago a big spoon or scoop was hung on the whitethorn bush which overhung the well. People came there regularly to drink the water and to bottle it to take away for use at home". (askaboutireland.ie)

Writing in 1850 W.R. Wilde had this to say of the well. "About a furlong's length to the west of the old church may be seen springs from a limestone rock of considerable extent; and appears first in a small natural basin immediately at the foot of the tree.

"Within the well are several trouts, each about half a pound weight. They have been there " as long as the oldest inhabitants can recollect," and, strange to tell, they are said not to have grown an ounce within that period. These fish are held in the highest veneration by the people, who, when the well is being annually cleansed of weeds, carefully preserve the blessed creatures, and replace them as soon as possible." (Wilde p. 142)

Getting There: A Personal Reflection

The Castlekieran monastic site is not only off the main roads, it is also invisible from the road. As usual, my wife and I, when searching for High Crosses, had a general idea of where the site was. We were sure we could get within a few kilometers at the most. We took the R 147 west out of Kells. After about three miles without any sign posting for Castlekieran we followed our typical pattern. We stopped to ask directions from a local. In this case it was a young man in the front garden of his home. He knew the Castlekeran site and gave us directions on how to get to the right road.

The route was still a bit confusing, but we were pretty sure we were on the right road when we came to Kieran's Well on the left side of the road. We stopped there to enjoy the beauty and spirituality of the place before continuing on to search for the monastic site. My wife was keeping an eye out on the left and as much as possible I kept an eye out on the right while driving slowly. We were looking for any sign of an old graveyard. We didn't see one. At one point, we stopped in the driveway of a two story yellow farm house to consult the maps we had with us and review the directions we had received.

After another half mile we saw a woman standing in her driveway beside her car. I stopped, got out and began to walk across the road to ask if she could give us further directions. As I did this, a young boy of perhaps five or six got out of the car. He saw me coming and called out to me, "Are you looking for Barney?" I found this amusing because, of course, my name is Barney, and I said so as I approached the lad. It turned out that the woman was his grandmother and that his grandfather was known as Barney.

The grandmother gave us very exacting directions. They went something like this, "Go back the way you came. You will pass a two-story farm house on the right that is occupied. Then you will come to another two-story farm house on the right that is derelict. When you come to the third two-story farm house on the right, a yellow house, stop just before you reach their driveway. You will see a gate that leads into their farm yard. Go through that gate and through the farm yard and you will come to the edge of a field. Across the field you will see the cemetery where the crosses are located."

Of course the two-story yellow farm house was the same house where we had stopped in the driveway less than twenty minutes before.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 27 4 A. From the R147 At Camacross take the road that goes to the southwest. Cross under the N3 and take a left. Follow the road that parallels the N3 and take the first left. After about 0.6 km you will pass a Holy Well site on your left. In another 100 meters you will see a house on the left and then some outbuildings Go through the area with the outbuildings and there will be a path that leads to the graveyard where the crosses are located.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

References cited:

Askaboutireland.ie www.askaboutireland.ie/reading-room/history-heritage/folklore-of-ireland/the-holy-wells-of-meath-f/keenahene-loughan/

Bitel, Lisa M., Monastic Settlement and Christian Community in Early Ireland, Cornell University, 1990.

Celt, Corpus of Electronic Texts, http://www.ucc.ie/celt/publishd.html, Annals of the Four Masters.

Cogan, A. Catholic Curate, Navan, The Ecclesiastical History of the Diocese of Meath, the Diocese of Meath Ancient and Modern, Vol. 1, Dublin, John F. Fowler, 1862.

Harbison, Peter; The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey, Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

The Monastic City of Clonmacnoise and its Cultural Landscape, Management Plan 2009-2014, prepared by The Office of Public Works and Environment, Heritage and Local Government, 2009.

Merriam-Webster on line dictionary, www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/termon

NewAdvent.org, Kieran, Catholic Encyclopedia.

O’Connell, Phillip, “A Castlekieran Cross-Slab”, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 87, No. 2 (1957), pp. 167-168. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25509289

SOCOIN/TOBIN Consulting Engineers, "Response to An Bord Pleanála Kingscourt to Woodland Route Comparison Report" Prepared for EirGrid, 2008

Wilde, William Robert, The Beauties of the Boyne, and its Tributary, the Blackwater, James McGlashan, London, 1850. http://ia600300.us.archive.org/17/items/beautiesofboynei00wild/beautiesofboynei00wild.pdf

Colp Cross

Information on this cross comes from Harbison, 1992, pp. 59-60 and the photo below right is from Harbison, 1992, Vol. 2, Figs 176-177.

This cross was discovered by Canon Ellison at an unclear date. It was excavated by Kieran Campbell in 1981 and moved to the church porch. It is now located in St. Mary’s Church of Ireland in Julianstown. A cross base, to which the cross may have belonged, is located in the southeast corner of St. Columba’s church at Colp.

The cross is carved of sandstone, has an imperforate ring, stands 25” (64cm) high, is 24” (61cm) across the arms, and is nearly 8” (20cm) thick. The remains of a tenon on the bottom suggest the cross may have been supported below and there is a mortise hole on top. There is roll moulding around the cross.

East Face

In the center of the head is a low boss that sits inside two concentric ribs. There may have been interlace or fretwork on the boss. The arms and shaft have interlace. The top of the cross is broken.

West Face

The center of the head bears a crucifixion. Jesus’ body is elongated and his arms are very thin. The arms slope upward, indicated he is hanging on the cross. He is flanked by Stephaton and Longinus. There is an unidentified figure at the end of each arm. Below Jesus’ feet is a spiral “out of which two serpents unroll themselves. One of the serpents from each of these spirals crosses a serpent from the other spiral and runs out along the bottom of the cross. The other two serpents respectively curl outwards and upwards in a semi-circle, terminating near the outer side of Christ’s leg.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 59)

Cross-Base

The base is located between the church and the southeast corner of the churchyard. It tapers from bottom to top and stands just under 14 inches in height. There is a mortise in the center.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 28, 4 F. Colp is four km east-south-east of Drogheda. It is located in the upper right corner of the map to the left. Julianstown (Road Atlas page 28, 4 F) is south of Colp along the R132. Take the R150 east at Julianstown. St. Mary’s Church will be on your left. See the upper right corner of the map to the right.

Maps are cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Source Consulted

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Dulane Cross

Introduction to the Site

The old churchyard at Dulane was the site of an early Irish monastery established in the sixth century by Saint Cairnech. The site was known in the Annals as Tulén, or Tuilián. Saint Cairnech was almost certainly the British saint known as Carannog (Carantocus). The first life of Cairnech states that he changed his name to the Irish Cernach, presumably upon his arrival to do missionary work in Ireland. His feast day is 16 May. Dulane was his chief monastery.

There is some reason to associate Cairnech with Saint Patrick. By the ninth century Cairnech was a saint of some importance. “In the later, probably ninth-century, prologue to the Senchas Már, the principal early Irish law book, it was claimed that a panel of bishops, poets, and lawyers compiled the book; the three bishops were Patrick, his successor, Benén, and Cairnech.” (Stalman & Charles-Edwards) The account could be accurate or it may be part of a manufactured history intended to connect Dulane with Armagh, the See of Patrick.

The only remains on the site are a ruined church. It is described as “remarkable for its west gable, which has projecting antae and a massive cyclopean doorway. This single-cell buildings with antae may be dated between c 8 and c 12; Dulane might well be of the early period, and is recorded as being burnt in 920, on the same day as the church at Kells.” (Casey & Rowan, p. 337) In the references to Dulane below, from the Annals of the Four Masters, there is no mention of the 920 burning. This entry may appear in another of the annals.

In his book Irish Ecclesiastical Architecture, Arthur C. Champneys offers the photograph (left) of the doorway of the church, seen from the inside. His book was published in 1910 so the photo is from that period or before. The cyclopean doorway is defined by the huge stone that forms the lintel. Antae refers to an extension of the side walls beyond the west wall of the church, a feature not seen in this photo.

In the Annals of the Four Masters we find the following references to Dulane. (Cogan, p. 134)

754 CE Dubhdroma, Abbot of Dulane, died.

781 CE Faebhardaith, Abbot of Dulane, died.

870 CE Maeltuile, son of Dunan, successor of Tighernach and Cairneach, i.e., of Dulane, died, he was a bishop.

886 CE Dulane, Ardbraccan, and Donaghpatrick were plundered by the Danes.

919 CE Ciaran, Bishop of Dulane, died.

936 CE Maelcairnigh, Abbot of Dulane, died.

943 CE Maeltuile, Bishop and Abbot of Dulane, died.

949 CE Dulane, Kells, and other monasteries were plundered by the Danes.

967 CE Maelfinnen, Bishop of Kells, Abbot of Ardbraccan and Dulane, died.

1170 CE Dulane was plundered by Dermod Mac Murchadh, King of Leinster, and the foreigners.

After the Anglo-Norman invasion, the abbey of Dulane pined away, and henceforth we find it a parish church.

The High Cross:

In his discussion of Dulane, Peter Harbison notes that “Professor Etienne Rynne has kindly drawn my attention to the fact that the topographical files of the National Museum in Dublin make mention of a cross-fragment which Siobhan de hOir and her late husband Eamonn discovered in long grass in the south-western quarter of the old churchyard at Dulane, but which is no longer traceable above ground.” He goes on to reference the photograph (right) and offer the following description. “Judging by photographs (Fig. 238), the fragment represents part of the arm of a cross with traces of the stump of a ring, and with the edges bearing a roll-moulding. The end of the arm has a raised, but apparently undecorated, panel. The cross may have stood in the base with roll-mouldings (Fig. 237) still visible in the churchyard.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 76 and plates 237, 238)

Site Photos:

The photos below were taken at the site in 2011.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 27 4 D. The site is located north of Kells to the east of the R164 between 2 and 3 km north of Kells towne center.

The map to the left is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Resources Consulted:

Casey, Christine and Rowan, Alistair John. North Leinster: The Counties of Longford, Louth, Meath and Westmeath, Yale University Press, 1993, 576 pages.

Cogan, Anthony. The Ecclesiastical History of the Diocese of Meath, Ancient and Modern, Dublin, 1862.

Harbison, Peter; The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey, Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Stallmans, Nathalie and Charles-Edwards, T. M.. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: Meath, saints of (act. c. 400 - c. 900), Oxford University Press, 2004-2012. Found online @ http://oxforddnb.com/view/printable/64439

Duleek

The Monastery

The Dublin Penny Journal of December 6, 1834 suggests a date of about 488 for the founding of an Abbey at Duleek. (Penny Journal p. 181) The supposed founder of Duleek was St. Cianan (Keenan) who was said to have been baptized by St. Patrick and ordained a bishop in 472, which might suggest a bit earlier date for the founding. Duleek’s golden ages seems to have been in the 7th and 10th centuries. During that time the Annals of the Four Masters states that it rivaled the great houses of Armagh and Clonmacnoise. The church and abbey were dissolved by Simon de Rochfort following the Norman invasion. (Taillamhain, p. 257)

Tradition has it that Duleek was the first place in Ireland to have a stone church and that this church may have been constructed by St. Cianan himself.

The photo to the left shows the ruins of a medieval church at Duleek

The Crosses

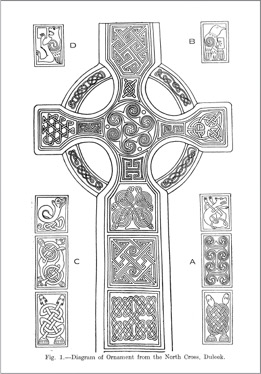

The following descriptions are based largely on the work of Crawford with some augmentation by Harbison. (Crawford pp. 1-10) The numbering system for the panels is Crawford’s and I have added some explanations of the part of the cross that each represents.

The North Cross

This cross is in good shape except for the missing cap. The base is plain and tapers toward the top. The sandstone cross is 6’ (1.83m) in height.

East Side: (Pictured to the right and in illustration below left)

E 1: Broken plait

E 2: Diagonal Fret modified to spirals under the center and step patterns at the sides.

E 3: Symbolic Vine with roots and fruit.

E 4: Lower constriction of shaft: Square Fret

E 5: Center of Head: Seven spiral coils raised to form rounded bosses.

E 6: South Arm: Knotwork interlace. (Harbison, 1992, p. 77)

E 7: South constriction of arm: Diagonal fret.

E 8: North Arm: An almost triangular interlace. (Harbison, 1992, p. 77)

E 9: North constriction of arm: A meander pattern. (Harbison, 1992, p. 77)

E 1: Upper constriction of Top: Interlace panel

E 11: Top: Triangular knotwork. Harbison refers to this as fretwork. (Harbison 1992, p. 77)

E 12, 13, 14, 15: Ring Segments: Interlace borders in the ring. Each is different.

The illustration to the left is found in Crawford’s article between pages 4 and 5.

West Side:

This face contains badly worn figural sculpture.

W 1: Seated Figure holds a child: Presentation or Holy Family. Harbison suggests Joachim and Anne Fondling the infant virgin. (Harbison, 1992, p. 77) Joachim and Anne are the names given by legend to the parents of the Virgin Mary. If Harbison is correct about this and the next two images, they reflect legendary rather than scriptural images on the cross.

W 2: Two seated figures face one another. The hand of one is on the head of the other. Harbison mentions several interpretations: An Angel brings bread to the Virgin in the Temple; The Visitation, The Anointing of David and the meeting of Paul and Anthony. (Harbison, 1992, p. 77)

W 3: Two seated figures face and clasp hands. Harbison suggests Joachim and Anne Greeting one another at the Golden Gate. (Harbison, 1992, p. 77)

W 4: Crucifixion with sponge and spear bearers.

W: Top: Large seated figure holds small object and faces smaller seated figure. A third small figure is below the larger figure. Harbison suggests Saints Paul and Anthony overcoming the devil. (Harbison, 1992, p. 77)

W 6: North Arm: A seated ecclesiastic with a crooked staff, Harbison suggests St. Paul the Hermit. (Harbison, 1992, p. 77)

W 7: The South Arm: Ecclesiastic seated and holding a tau crosier. Harbison suggests St. Anthony the Hermit. (Harbison; 1992, p. 77)

Before the figures on each arm is a round object that may be a human head. These may also represent the sun and moon.

W 8, 9, 10, 11: Ring Segments: Spiral patterns on the ring segments with four bosses.

North Side:

N 1: Two interlaced serpents.

N 2: Spiral design of C-shaped curves.

N 3: Dog-like animal with interlaced legs and tail.

N 4: Underside of the ring has two interlaced borders.

N 5: End of arm has a winged lion grasping an upright pole.

N 6: Upper ring had interlaced borders. It is much worn.

N 7: The eagle symbol of St. John and Evangelist.

South Side:

S 1: Two intertwined serpents.

S 2: Two intertwined animals back to back with interlaced tails.

S 3: Serpent, eared and with tail plaited.

S 4: Under ring has interlaced borders.

S 5: End of arm a Griffon.

S 6: Upper ring worn but similar to that on opposite side.

S 7: Winged lion of St. Mark.

South Cross:

This cross has a large base that is without decoration. The shaft is missing. The head has a perforated ring and is 3’ 5” (1.04m) across the arms.

North Face: (See the photo to the left.) There is a Crucifixion scene at the center that contains the sponge and spear bearers. Harbison notes in addition there is an angel above each of Jesus’ arms. (Harbison, 1992, p. 78) On the arms, centered on the ring are bosses. The lower one is missing and all are worn. Each seems to have had four triquetra knots joined at the center. (Crawford p. 9)

Sides: The sides are undecorated. (Harbison, 1992, p. 78)

South Face: This face closely resembles the north face but the bosses are plain and the center has a simple cross with rounded angles. (Crawford p. 9)

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 28 5 E. Duleek is on the R150. The site is close to towne center. Take a street to the right and the site is about 100m along that road. The ruins of the Abbey and the graveyard will be visible

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Crawford, Henry, “The Early Crosses of East and West Meath”, The Journal of the royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Sixth Series, Vol. 16, No. 1 (Jun. 30, 1926), pp. 1-10.

“Duleek Church, County Meath,” The Dublin Penny Journal, Vol. 3, No. 127 (Dec. 6, 1834), p. 181.

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Morris, Henry, “Duleek”, Journal of the county Louth Archaeological Society, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Jul., 1904), p. 61.

Taillamhain, Seamus Ua, “Duleek and Its Environs”, Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society, Vol. 2, No. 3 (Oct., 1910), pp. 257-261.

Fennor Cross

The only information I find concerning the Fennor cross is from The Slane History and Archaeology Society as noted below in Resources Consulted.

The Abbey

An abbey was founded at Fennor, just south of the River Boyne from Slane, in the early Christian period. The exact date is unknown. St. Neachtain, who was a disciple of St. Patrick, was the patron saint.

The following notations regarding Fennor can be found in the Annals of the Four Masters and other Irish Monasticons.

804 Maelforthartaigh, Abbot of Fennor and Kilmoon, died.

827 Maelumha, Prior of Fennor, died.

833 The plundering of Fennor, Slane and Glendaloch by the danes.

837 Tigernach, Abbot of Fennor and other churches, died.

843 Fiachna, Abbot of Fennor, died.

847 The cross which was on the green of Slane was raised up into the air, it was broken and divided, so that part of it’s top fell at Teltown and Fennor.

882 Eochu, Abbot of Fennor and Kilmoon, died.

902 Ferghil, Biship of Fennor and Abbot of Indiedhnen, died.

1024 Fachtna, Professor and Priest of Clonbmacnoise, airchinneach of Fennor and Indiedhnen, and the most distinguished Abbot of the Gaedhil, died at Rome, where he had gone on a pilgrimage.

Following the Anglo-Norman invasion, Fennor continued as a parish church.

The Cross

The description of the cross comes from the Historic Environment Viewer, County Meath, High Cross, Slane (ME019-025001-)

The cross is a fragment of a cross-head, on display at the west end of the Roman Catholic church in Slane. The west face has a crucifixion and the east face has perhaps six bosses in an interlace pattern. The cross fragment measures 23” (0.6m) wide; 22” (0.56m) high and 9.5” (0.24m) thick.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 27 4 D. In the town of Slane, just north of the intersection of the N51 and the N2 and on the right side of the road going north is the Roman Catholic Church.

Sources Consulted

Historic Environment Viewer: http://webgis.archaeology.ie/historicenvironment/.

Slane History and Archaeology Society: http://slanehistoryandarchaeologysociety.com/index.php/slane-in-local-history/3-fennor#top.

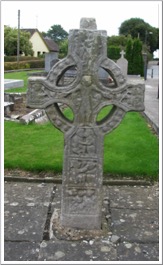

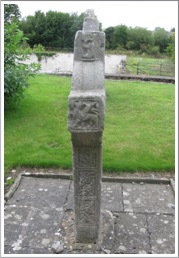

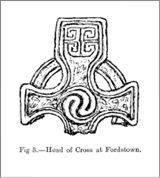

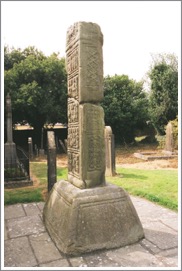

Girley/Fordstown Cross

I find no information at all about the history of this site. The cross-head is now in the OPW National Monuments depot at Trim (ME036-079 . . . )

The cross head is 20” (51cm) across the arms. There is roll moulding. In the center of the crossing is a whorl of two-looped arms. In the upper arm there is a square of fret work. The arms have traces of knots. (Crawford p. 10)

Sources Consulted

Crawford, Henry S., “The Early Crosses of East and West Meath,” The Journal of the royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Sixth Series, Vol. 16, No 1 (Jun. 30, 1926), pp. 1-10

Kells

The Monastery

The following historical summary relies on the work of Helen Roe in “The High Crosses of Kells.”

The earliest record of Kells comes from the early 9th century. However, it seems clear that Kells was originally the site of a hill fort. In the 6th century the site was known as Ceanannus or Head Fort. Tradition suggests that High King Diarmaid mac Fergusso Cerrbhcoil, a cousin of St. Colmcille gave this property to St. Colmcille.

The earliest record of Kells comes from the early 9th century. However, it seems clear that Kells was originally the site of a hill fort. In the 6th century the site was known as Ceanannus or Head Fort. Tradition suggests that High King Diarmaid mac Fergusso Cerrbhcoil, a cousin of St. Colmcille gave this property to St. Colmcille.

The photo to the left shows the unfinished cross with the round tower in the background.

The documentary record begins when the Iona community left Iona and settled at Kells. This suggests that there was already a Columbian monastery there, and the monarch at the time Aedh Oirdhnidhe must have approved the move and new development. A note in the Annals of the Four Masters indicates that the church of Colmcille at Kells was destroyed. This was probably the existing church and at about the same time the Annals of Ulster notes the construction of a new civitas at Kells to accommodate the Iona community.

Abbot Ceallach, the abbot of Iona at the time of the move, was responsible for the construction at Kells. In 920 the stone church of Colmcille, possibly built by Ceallach was destroyed by the Norsemen. The succeeding church was burnt in 1050.

“The story of Kells is one of violence and destruction. Local kings and even High Kings profaned the sacred site by armed conflict, murder, and political assassination.” (Roe, p. 4) For example, Godfrey, Lord of Dublin, sacked Kells in 949 and took “3000 prisoners and gold, silver, raiment, wealth and goods of every sort.” (Roe, p. 4) This entry alone suggests the wealth of the monastery and its size.

Fire, a recurrent problem in communities made largely of wood, burned all or part of Kells at least 15 times, according to the records.

The fame of Kells is particularly associated with the illuminated gospels that were probably started on Iona and perhaps finished at Kills and that eventually took the name of the monastery.

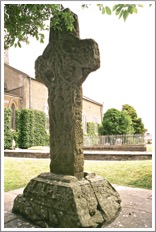

The Crosses

There are five crosses in Kells. The North Cross, South Cross, West Cross, and East Cross are in the church yard. The Market Cross is located in front of the Heritage Center. The North Cross consists of only a cross-base. Roe suggested possible dates for the various crosses. She dated the South Cross earliest, possibly the middle of the 8th century. The Market Cross and West Cross from the mid 9th century, and the unfinished East Cross from the 12th century. (Roe, pp. 6-9)

The West or Broken Cross

This was an imposing cross with the shaft fragment standing 13’ (3.96m) high. It may have been essentially intact into the 17th century. Harbison notes that it was probably re-erected at some point in time and turned wrongly. Harbison’s descriptions reflect the position of the cross in the Market Square and do not align with the position of the cross in its present location. (Harbison, 1992, p. 101)

East Face: (See the photo to the right.)

Base: The base has no apparent decoration.

E 1: The Baptism of Christ: John the Baptist stands at the right and pours the water of baptism over the head of a smaller Jesus. The water has two sources that conform to Irish tradition that the baptism took place at the convergence of the JOR and DAN. Above the head of Jesus a dove, representing the Holy Spirit, descends. On the left of the panel stand two figures who observe the baptism.

The photo to the left highlights the lowest three panels on the east face of the shaft.

E 2: The Miracle of Cana: Jesus stands on the left with a seated Mary before him asking his assistance. (Harbison, 1992, p. 101) Roe identifies the seated or kneeling figure as the steward of the feast. (Roe p. 47) To the right are two rows of figures and the shapes of six water jugs can be discerned.

E 3 left: This panel offers several possible interpretations. Harbison and Roe divide it into left and right scenes. Without going into detail, Harbison favors an interpretation of the Raising of Lazarus or Jesus Heals the Lame Man at the Pool of Bethesda. (Harbison, 1992, p. 101) Roe favors an interpretation of David playing the harp. (Roe, p. 49) The left figure is either Jesus or David. A domed figure above and to the right of Jesus could be a tomb a harp or an arch near the pool of Bethesda. A prostrate figure at Jesus feet could be Mary or Martha pleading for Jesus to take action or the man by the pool.

E 3 right: This panel also offers a number of possible interpretations. Jesus Delivers the Adulteress or the Woman of Samaria at the Well, the Presentation in the Temple or Three unidentified figures. A figure in the center of the panel appears to be seated and two figures approach from the right.

The photo to the left illustrates the upper three panels of the east face of the cross.

E 4: The Washing of the Child Jesus or the Presentation at the Temple. Harbison sees the figure second from the right as the child Jesus in a bath-tub. The other figures seem to hold water bottles for washing. (Harbison, 1992, p. 102) Roe sees the figure second from the right as Simeon behind a table or alter with the second figure from the left being Mary carrying the infant Jesus and the figure farthest right holding doves for the offering. (Roe, p. 49)

E 5: Three Wise Men questioning Herod. Harbison sees two guards on the left protecting Herod who stands in front of them. The next three figures are the wise men questioning Herod about the prophesy and where they might find the new born king. (Harbison, 1992, p. 102)

E 6: The Entry of Jesus into Jerusalem. This broken panel clearly has a figure riding an animal in the center of the panel.

South Side: (See the photo to the right.)

The sides are both decorated with designs. Here we have Harbison’s descriptions. (Harbison, 1992, p. 102)

S 1: A sunken cross has spiral-decorated bosses at the ends of the arms that link with other bosses above and below. Some bands appear to be gotten by animal figures that emerge from the bosses.

S 2: Interlace in semi-circular patterns.

S 3: Interconnecting bosses.

S 4: Fretwork with spiral terminals.

S 5: Interlacing serpents with curling tails.

West Face: (See the photo below left.)

Base: There may have been an inscription on the base. Macalister read it as “A Blessing for Artgal”. (Roe, p. 51)

W 1: Adam and Eve Knowing their Nakedness

W 2: Noah’s Ark: A large figure appears with head above the arc and feet below. This figure may represent Christ, the Logos or Word. The image would then focus on God’s power to deliver the faithful. (Roe, p. 51)

W 3: Moses turns the waters of Egypt into Blood: There are two figures on the left, probably representing Moses and Aaron. There are two figures on the right probably representing Pharaoh and a guard. There are two half-figures in the lower foreground that may represent Pharaoh’s servants. (Harbison, 1992, p. 103)

W 4: The passage of the Israelites through the Red Sea: Harbison interpreted the scene as depicting Pharaoh and his army trapped in the sea as the Israelites, no longer visible, have crossed the sea. (Harbison, 1992, p. 103)

North Side: (See the photo to the right.)

N 1: Design with two human heads surrounded by biting serpents that emerge from bosses.

N 2: An upright lozenge is in the center of the panel. It is decorated with bosses. The corners around the lozenge contain fretwork.

N 3: Interlace of four animals with additional interlace that contains animal-headed terminals.

N 4: Decoration on this panel is no longer discernible.

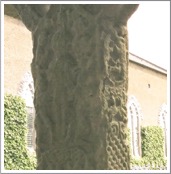

The East or Unfinished Cross:

This cross is of interest because it shows the preliminary stages in the carving of a High cross. Even without the upper arm and presumably a cap, the cross stands 14’ (4.27m) in height. The shaft and head were on the ground separately until the late 19th century, when the cross was erected.

East Face: (See the photo below to the left.)

Shaft: There are several square and rectangular panels that have yet to be carved on.

Head: A crucifixion scene appears in the center. Stephaton is on the left offering vinegar. Longinus is on the right piercing Christ with his lance. There is an angel on each side of Jesus’ head. Jesus is especially tall in this carving. On the right arm Harbison has suggested the unfinished panel may represent the Holy Women at the Tomb. The angel on the left addresses the three women who approach the tomb. (Harbison, 1992, p. 112)

South Side:

The shaft is undecorated. The underside of the ring has fretwork flanked by interlace on the right. The underside of the arm has sunken crosses.

West Face: (See the photo to the right.)

The shaft and head are not decorated but contain some panels.

North Side: The shaft is undecorated. The underside of the ring has interlace on the east side. The underside of the arm is like that on the south side.

The Cross of Saints Patrick and Columba or the South Cross

This cross stands about 11’ (3.35) high and Roe compares some of its decoration to motives in the Book of Kells. She also relates it to the South cross at Clonmacnois and the cross at Killamery. (Roe, pp. 10-11)

East Face: (See the photo to the left.)

Base: The scene here has been described as Noah and the animals and as a hunting scene. There is a man on the right with a spear and shield. He has two dogs. In front of him are a hare, a bird, a quadruped with a boar above it and a stag.

On the upper portion of the base is an inscription from which the cross receives one of its names “The Cross of Patrick and Columba.” Below it there may have been an additional inscription “which Muiredach made.”

E 1: Interlace with nine circular devices.

E 2 left: Adam and Eve knowing their nakedness.

E 2 right: Cain Slays Abel

E 3: The Three Children in the Fiery Furnace

E 4: Daniel in the Lion’s Den

Head: Center: A square panel has interlace but the center has a roundel with seven bosses.

South arm: The Sacrifice of Isaac.

North arm: Saints Paul and Anthony break Bread in the Desert.

Contraction of Upper arm: Two crosses fish.

Top: David plays before Saul.

Ring: Panels of interlace blanked by rounded mouldings.

South Side: (See photo to the right.)

Base: Interlace

Shaft: Various decorations. Fretwork, interlace with birds emerging, interlace with two quadrupeds.

Head: Under the ring interlace probably containing two animals. Under the arm: Two animals seen from above. End of arm: David slays the Lion. (See the photo below left.)

West Face: (See the photo to the left.)

Base: A chariot procession. Roe suggests this may represent the transfer of relics. (Roe, p. 19)

W 1: Human interlace above a band of fretwork.

W 2: The Crucifixion: (See the photo to the right.) This is one of only a few crosses that has a crucifixion scene on the shaft of the cross rather than on the head. Above Jesus’ head is an eagle. To the left Stephaton offers vinegar and on the right Longinus pierces Jesus with a lance. Small figures sit on either side of Jesus’ head and each holds an object that may be the Sun and Moon or Ocean and Earth.

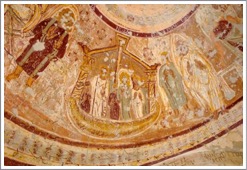

Head: Majestas Domini or Christ in Glory. (See the photo to the left.) Christ holds a cross-staff over his left shoulder and a blossoming scepter over his right. He is flanked by winged beasts. In the contraction of the arm is what may be an angel holding up a circle with the lamb of God.

Arms: Each arm has a central boss with interlinked bosses around.

Top: There are interlinking C-shapes that terminate in bosses. This pattern is surrounded by other interlinked bosses.

Ring: Interlace with roll mouldings. The interlace may have animal heads.

North Side:

Base: Knots of interlace.

Shaft: Decoration includes fretwork below animal interlace that forms spiral shapes that have open-mouthed beast-heads. Above that is vine-scroll that is inhabited by lambs and birds.

Head: Under the ring two animals seem to devour a serpent between them. Under the arm two animals devour a two-headed creature.

End of Arm: David slays the Lion

Upper side of arm: interlace.

Top: Saints Patrick and Columba

The Market Cross

This cross is not located within the bounds of the monastery. It once stood in the Market Square, where it was erected in 1688 as noted by an inscription on the west shaft. It is presently located in front of the Heritage Centre in Kells. The upper arm and cap are missing. The cross now stands 9’ (2.74m) in height and has an arm span of nearly 5’6” (1.68m). The base adds nearly 2’ (61cm) to the height.

East Face: (See photo to the right. The descriptions represent the present alignment of the cross and align with the descriptions of Roe.)

Base: A procession of 4 horsemen.

Plinth: spiral decoration.

E 1: Christ in the Tomb

E 2: David Acclaimed King of Israel. A central figure is flanked by six figures on each side holding shields.

E 3 left: Adam and Eve Knowing their Nakedness.

E 3 right: Cain Slays Abel.

Head Lower: David Playing his lyre.

Head Center: Daniel in the Lion’s Den

Head Upper: Adam and Eve at Labor

South Arm: Sacrifice of Isaac

North Arm: Temptation of st. Anthony

Ring: Various interlace patterns

North Side: (See photo to the left.)

Base: There is a hunting scene that includes two centaurs a dog, birds and a quadruped.

N 1: The Kiss of Judas or Jacob and the Angel: While most interpreters see this as Jacob wrestling the Angel, Harbison, based on his identifications of other images on this face of the cross prefers to see it as the Kiss of Judas. (Harbison, 1992, p. 104)

N 2: Peter cuts off the ear of Malchus.

N 3: The Arrest or Mocking of Jesus.

N 4: Unidentified.

Underside of Ring: (See Photo to the right.) Four squares of fretwork are flanked by 4 humans with interlaced legs.

Under Arm: Human interlace.

End of Arm: Saints Paul and Anthony Break Bread in the Desert.

Top of Ring: was probably interlace.

West Face: (See photo below left..)

Base: Hunting Scene: A man on the right herds or hunts a number of animals.

W 1: This panel was defaced and replaced with an inscription that reads:

“This cross was erected at the charge of Robert Balfe of Gall Irstowne Esq being sovereign of the corporation of Kells anno Dom, 1688.” (Roe, p. 35)

W 2: Suffer Little Children to come to Me.

W 3: Healing of the Centurion’s Servant

W 4: Multiplication of Loaves and Fishes

Head: (See photo to the right.)

Head Center: Crucifixion with Stephaton and Longinus

Arm Constrictions: The Denial of Peter. On the right a cock faces Jesus. On the left Peter seems to warm his hands over the brazier.

North Arm: St. Anthony overcomes the devil in guise of a woman.

South Arm: Saints Paul and Anthony overcoming the devil in human form.

Ring: Interlaced coiling animals.

South Side: (See photo below to the left.)

Base: Battle Scene with two men on the left with spears opposing three figures on the right with swords. All carry shields.

S 1: A possible hunting scene has a stag with a dog on its back and a mutilated human figure to the right that seems ready to strike with a weapon.

S 2: The Judgment of Solomon. Two soldiers hold a figure upside down between them, one holding a sword.

S 3: Samuel Anoints David. One figure kneels before another who seems to bless him.

S 4: The Pillar of Fire. This scene does not show the pillar but instead shows the hand of God in the upper right of the panel. Below are the Israelites and to the left is Moses.

Underside of Ring: There is fretwork in the center and on each side are human figures that seem to pull each other’s beards.

Underside of Arm: Bosses with serpents emerging and triangular knots of interlace in the voids.

End of Arm: David Slays the Lion.

Top of Ring: A meander pattern in the center has interlace on either side.

Decorated Base or North Cross: (See the photo to the right.)

This base has bands of interlace that run horizontally with raised bands between.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 27 4 B. All the crosses except the Market Cross are located at the Church in town center, indicated by four circles on the map below. The Market Cross is located near the right side of the map below.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

Roe, Helen, M., “The High Crosses of Kells”, Meath Archaeological and Historical Society, 1988.

Killary cross-shaft and base, cross-head and base fragments

In a graveyard defined by an earthen bank stand the ruins of a church, a partial cross shaft in a base and nearby a fragment of another cross-head in the mortise of a second cross base. Two additional fragments with decorated panels may have come from this site and are now in the possession of the National Museum of Ireland.

Little is known of the history of the site. It is possible it was founded in the late 5th century by St. Ivarii (lobhar of Bergerin?). His death is dated to between 504 and 510. (MeathHeritage.com)

The name Killary may derive from the Irish Cill Fhoibhrigh, meaning favored or influential church. (Meehan, p. 287)

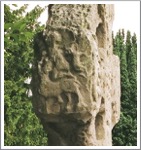

The Cross-shaft and base

The shaft is about 4’6” (1.37m) in height and early 16” (41cm) wide.

East Face

E 1: Adam and Eve Know their Nakedness. Adam and Eve stand under a tree and cover their nakedness while the serpent coils up the tree and turns it head toward Eve on the left.

E 2: Noah’s Ark. The ark is pictured resting on Mount Ararat. A dove with an olive branch sits on the upper deck. The graceful ark is in the design of a viking ship. It also seems to have artistic connections with the Egyptian Coptic church. Porter points to the similarity to an ark in the Khargeh Oasis tomb in Egypt, pictured below left.

(Source: http://www.egypttoursplus.com/al-bagawat/, 2017. Porter, p. 106)

E 3: The Sacrifice of Isaac. In this scene Abraham is on the right while Isaac bends over a stepped altar and an angel holds the foot of a ram behind his back. Symbolically, the stepped base is said to recall the Hill of Golgotha on which the cross of Jesus stood. (Stalley 1996, 11)

E 4: Daniel in the Lion’s Den. Daniel is in the center with an upright lion on each side of him.

South Side:

S 1: Animals emerge from bosses. Two of them have circular objects that may be human heads between them at the top of the panel.

S 2: Animal interlace that may also have human heads between animals at the top.

S 3: Animals emerge from six bosses and again hold something between their heads, this time in the center.

S 4: An animal descending from the top right and a second possible animal.

West Face

W 1: The Annunciation to the Shepherds. Animals face an angel on the left. On the right a shepherd raises his hand.

W 2: The Baptism of Christ. John the Baptist is on the right. The figure of Jesus is smaller than that of John. The waters of the Jordan flow from two discs that represent the sources of the Jordan in the rivers Jor and Dan. Above these discs is a figure that may be an angel. Porter notes that “In none of the Irish crosses except Killary, so far as I can observe does John the Baptist pour the water on the head of Christ with a baptismal spoon. Such a spoon was however used by the early Celtic saints.” (Porter, p. 108)

W 3: The Adoration of the Magi. Mary holds Jesus while Magi, two behind her and one in front, bear gifts. A boss represents the star.

W 4: The Marriage Feast of Cana. This identification is speculative as the panel is broken. There are six water jars visible, leading to the possible identification.

North Side

N 1: David with the Head of Goliath

N 2: Interlace

N 3: Identification is uncertain but it could be David or St. Ciaran or the Temptation of St. Anthony.

N 4: What appear to be two animal heads cross at the bottom of this broken panel.

The above identifications rely largely on Harbison, 1992, pp. 124-5.

Cross Head Fragment and Base

A small fragment of the arm and head of a cross is located near a base with roll mouldings. On my visit the fragment sat in the mortise of the base as pictured to the right.

The fragment is undecorated. See the photo to the left.

Two Shaft Fragments

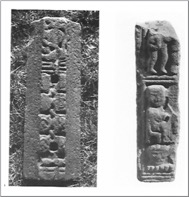

Two shaft fragments were found in the churchyard by John Bradley in 1986. The photographs to the right were taken by Heather King and appear in Harbison, 1996, Vol. 2, Figs. 417 a-b. They were used as window frames in the 16th century which badly damaged them.

Fragment 1

This fragment is shown to the right in the photo to the right. It was broken vertically to be used in a window and so we have but half of each of the panels. It is 21” (53cm) high and 8” (20cm) wide.

Lower Panel: A figure is seated in a chair and may have faced another figure to the right. Below this figure is a human head and six bosses which may be baskets and could lead to an identification as the Multiplication of the Loaves and Fishes.

Upper Panel: The legs of a figure are present along with a U shaped object. There was a figure to the right and this scene may represent the Traditio Clavium, Jesus giving the keys to heaven to Peter.

Fragment 2:

This fragment is to the left in the photo above right. It measures 19” (48cm) in height and is 7” (18cm) wide.

Lower Panel: There are eight joined knots of interlace with an unidentified object below.

Upper Panel: This may contain an animal ornament but identification is uncertain.

The descriptions above are based on Harbison, 1992, pp. 125-6.

Getting There: See the Road Atlas page 27 3 C. Located on the road between the N52 and Lobinstown.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

egypttoursplus.com: http://www.egypttoursplus.com/al-bagawat/.

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

MeathHeritage.com: Heritage and Culture in Meath: http://www.meathheritage.com/index.php/archives/item/me00562-killary-church.

Meehan, Cary, "The Traveller’s Guide to Sacred Ireland", Gothic Image Publications, Gastonbury, Somerset, England, 2002.

Porter, Arthur Kingsley, "The Crosses and Culture of Ireland", New Haven, Yale University Press, 1931.

Stalley, Roger, 1996; "Irish High Crosses", Country House, Dublin.

Knock

Little appears to be known about this site. What we have now is a graveyard that is outlined by an earthen bank and hedges. It is known that in the 19th century there was a church on the site but there is no sign of it now, and it was certainly not the church of an early date.

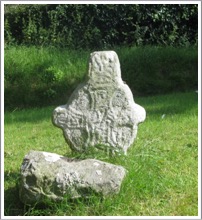

On the site is the head of a cross. It is irregular in shape with an imperforate ring. It stands 25.5” (65cm) above ground level and measures just short of 19” (48cm) across the arms. Harbison speculates that its present appearance may be a result of a reworking. The date of the carving is uncertain and may be post 1200. Harbison lists it because “there is not sufficiently strong evidence to date this cross later than 1200.” (Harbison, 1992, p. 135)

East Face: (See photo to the right.)

This face has a cross and interlace on the head and fretwork on the shaft.

West Face: (See photo to the left.)

There is also a cross on this face. It is filled with angular designs and there is interlace on the shaft.

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 27 4 C. Located east of the R162 about 3km northeast of Wilkinstown.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Sources Consulted

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

meathheritage.com: http://www.meathheritage.com/index.php/archives/item/me00578-knock-church.

egypttoursplus.com: http://www.egypttoursplus.com/al-bagawat/.

Harbison, Peter; "The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey", Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH, Bonn, 1992. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Photographic Survey; Volume 3: Illustrations of Comparative Iconography.

MeathHeritage.com: Heritage and Culture in Meath: http://www.meathheritage.com/index.php/archives/item/me00562-killary-church.

Meehan, Cary, "The Traveller’s Guide to Sacred Ireland", Gothic Image Publications, Gastonbury, Somerset, England, 2002.

Porter, Arthur Kingsley, "The Crosses and Culture of Ireland", New Haven, Yale University Press, 1931.

Stalley, Roger, 1996; "Irish High Crosses", Country House, Dublin.

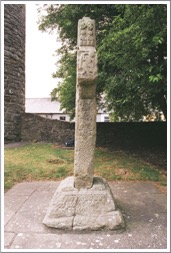

Nobber Crosses

Until the discovery of High Crosses at Nobber, the history of the site dated back only to the early Norman period. In 1172, Henry II of England granted the Lordship of Meath to Hugh De Lacy. De lacy in turn granted the Barony of Morgallion to Gilbert de Angulo, who had a motte and bailey constructed there. (http://www.meath.ie/Tourism/MeathsTownandVillages/Nobber/) With the discovery of high crosses the presence of an ecclesiastical settlement here seems almost certain. the cross fragments seem to date in the range of the late 9th to the 11th century.

The cross fragments include a cross base, “High cross 1” and “High cross 2”, all apparently from different crosses.

Cross Base

The cross base is located on the left inside the graveyard gate. It stands about 24” (61cm) above the ground. At ground level the base measures about 33” (84cm) in diameter and just over 16” (41cm) at the top. The base appears to have been decorated over most of the surface but most of the decoration is deteriorated to the point that any guess at the design is impossible. There are, however, two bands of interlace framed by a wide and narrow rib close to the top of the base. King suggests a date in the 10/11 century. (photo to the right and information from King, p. 21)

Cross One

This solid-ringed cross stands about 14” (36cm) above ground level and has a width of just under 13” (33cm) and a depth of just over 3” (7cm).

One arm is sheared off just inside the ring. (King, p. 22)

In the photos above, the west face is to the left and the east face to the right. (Photos from King, p. 22)

East Face:

On this face there is a cross inside a circle. At the center there is a small holed-boss. King identifies interlace around the boss and extending into the arms of the cross. (King, p. 22)

West Face:

On this face there is a holed boss at the center of the head inside a small circle. King states that the boss is “surrounded by a wheel of eight D-shaped sections within a larger circle.” (King, p. 22) The “Ds” at top, bottom and sides contain bosses, thus giving the impression of a cross.

Cross Two

This partial shaft stands just under 19” (48cm) above the ground and an estimated minimum of 6 additional inches (15cm) below ground. The width is 10” (25cm) and it is 5+” (14cm) deep. At some point in time it was repurposed as a window jamb, probably in the church. There was roll moulding but some of this has been removed. There is a combination of figures and interlace without frames. The shaft is largely undecorated. (King p. 23)

Getting There: See Road Atlas page 27, 3 C. On the R162. See the map to the left for the location of the crosses in Nobber.

The map is cropped from the Historic Environment Viewer.

Resources Consulted

King, Heather A., “Nobber’s Early Medieval Treasures Revealed”, Archaeology Ireland, Vol. 19, No. 3 (Autumn, 2005), pp. 21-24.

Nobber, http://www.meath.ie/Tourism/MeathsTownandVillages/Nobber/